Opening with the vibrant celebration of colours and exotic sounds of the Brazilian rainforest, our focus is drawn to a nervous exotic baby macaw bird called Blu who plucks up the courage to attempt his maiden flight. Predictably he tumbles towards the ground, making a soft spongy safe landing, before commotion strikes and an attack of human poachers in search of valuable exotic bird’s snatch Blu from his natural habit. Fate takes a turn, when Blu is discovered by a sweet little girl called Linda, after falling off the bird-smuggling truck during transportation. This human-animal relationship signals the beginning of his domesticated life as a pet in Minnesota. However, their idle lifestyle is soon challenged when Blu and Linda find out the extinction of their species is under threat and the only way to save them is to travel to Rio de Janeiro to mate with the last remaining female macaw, Jewel.

Rio, sits comfortably within the family-friendly adventure trope genre, following the story of Blu on his journey of learning how to fly which engages with themes of self-acceptance and a re-assimilation with his bird animality The film sets up his life in Minnesota where Blu enjoys his life as a pet, following a strict mundane routine. Rio personifies birds, presenting them as andromorphic by prescribing them a mixture of human and animal behaviours. This key feature is used heavily amongst most animation films and works by blurring the boundaries between animal and human forms, allowing the species to move fluidly between the two. This works to stimulate children’s emotions which creates an engaging narrative that is easy to follow. Blu’s andromorphic nature is set up within the starting scene as we are guided through a typical morning routine. This first medium shot captures Blu and Linda simultaneously brushing their teeth, swirling mouthwash and spitting into the sink (Fig.1&2).

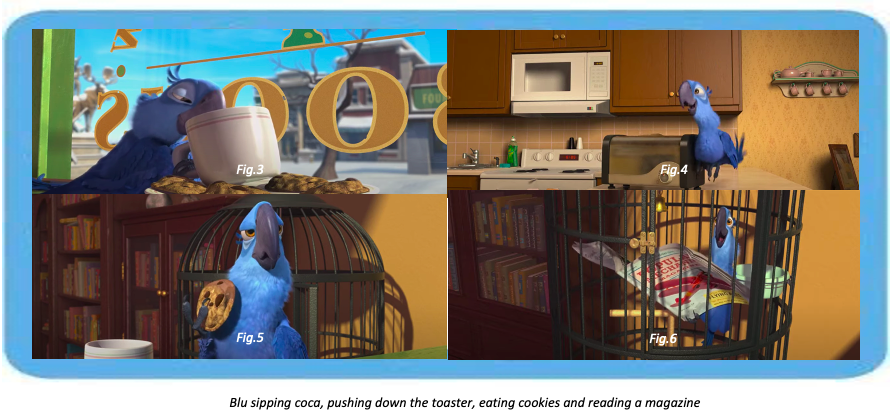

As the scene progresses, Blu carries out further human behaviours; pushing down the toaster, drinking cocoa and reading magazines (Fig 3,4,5,6) but also noticeably embodies animal traits too; using his beak and feet to complete tasks and squawking at Linda. Allowing Blu to embody both human and animal traits, enables the film to firstly play along with stereotypes of animal behaviour to establish an initial understanding for young audiences to follow, but also combines these established behaviours with anthropomorphic human actions which provide the film with a comical element. Animation is keen on creating this fluid movement between animal and human to generate a sense of relatability and the inclusion of animals, a vibrant colour palette and catchy soundscape all work together within the film to create a highly visceral, comical and playful film.

“Animal imagery is used to make statement about human identity”[1] within the film, and Rio leans into this idea by establishing an animal as the film’s protagonist. The film characterises Blu as a socially awkward outsider, immediately presenting him as a sympathetic character. This is done by presenting us with the idea that Blu cannot fly. This ties in with the core notion of the family film genre where the protagonist faces a central problem, usually alienating them from their species and must go on a journey of transition and discovery over the course of the film. This is seen within other animation narratives such as Ratatouille: where Remy takes a delight in cooking which is contrasted with the other rats’ careless perspective food, or during the Bee Movie: where Barry strives for a life outside the typical occupation of honey-making. In Rio, this is presented through the idea that Blu is an outsider because he cannot fly. By attributing these “traits and tropes readily known and acknowledged in the public domain”[2], (e.g., children have an understanding that birds can fly), the film succeeds in constructing a plotline that is accessible to adults and children without alienating either and is able to construct a likeable character, where viewers root for their success. Animals in animation have the ability to conform to but also confound pre-determined ideas and expectations about animals, because of the fluidity of the animation.

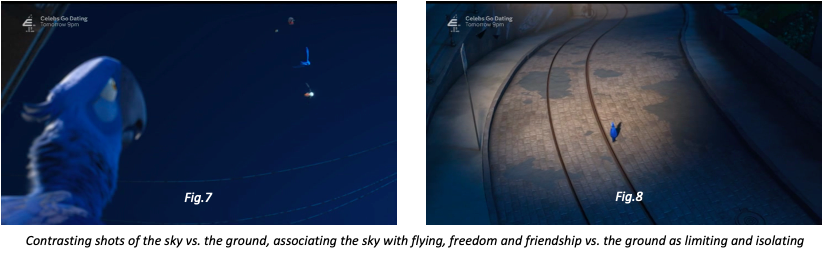

Rio uses the protagonist’s journey narrative to simultaneously tackle the oppositions of wildness vs. civilised within the animal world. As a domesticated pet in Minnesota Blu has no desire to fly, content in his routine, yet Wells expresses the fact “He is debilitated by an oppressive culture and made to submit to its conditions,”[3]. Within the oppressed setting of Minnesota, Blu is placed within an abnormal setting, a contributing factor to characterisation as an outsider.. As he journeys to Rio de Janerio on a quest for self-acceptance, he is reunited with more birds and similar animals which unlocks his desire to lean into his true animal form, something that he was careless about before. There is a shift within Blu’s character as he begins to adopt more dominant animal traits and loses human ones. Where at the start of the film he engages in heavily mundane human activities, as the film progresses, so does Blu’s desire to embrace his true animal characteristics and qualities. Wells secures this idea that “there is also a greater longing about the release of an animality into more appropriate conditions and contexts”[4]. This becomes apparent after Luiz breaks the chain between Blu and Jewel giving them freedom. This freedom immediately excites Jewel and the camera follows her and the other birds swooping around, laughing and singing. Yet in this moment of celebration, we are poisoned on the ground alongside Blu who stares longingly at the birds flying above. (Fig. 7). The camera then cuts to a wide overhead shot angled looking down over Blu on the ground, creating a sympathetic atmosphere as he walks along the dark street isolated and alone (Fig.8). This key moment establishes the idea that Blu must learn self-acceptance through an assimilation with his true animal traits; flying.

The film creates a journey narrative that is simple to follow for young audiences by using the already established idea that birds can and should fly. Through this narrative the film is able to tackle the oppositions of wildness vs. civilised, presented through a shift in Blu’s anthropomorphic nature. He transitions from a heavily human characterised bird to one that leans into his true animal form by the end of the feature, depicted in the final scene where he flies off into the jungle.

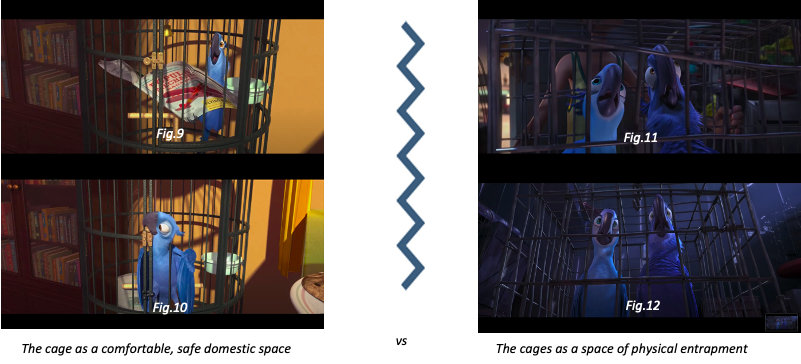

The film further plays with oppositions by tackling the idea of freedom vs. captivity through the motif of cages. The animation comments on the problems with bird smuggling and the black market within Brazil by using cages as a symbol of entrapment but also a metaphor for Blu’s freedom. At the beginning of the animation, Blu is depicted sitting comfortably within his cage reading a magazine (Fig.9&10). Here it is presented as a space of contentment, he actively opens the cage with ease, displaying this idea of free will and choice. Yet later on, when Jewel and Blu are captured by bird smugglers we are presented with a horrifying image of masses of captured birds. They are characterised as in distress, chattering and squawking loudly, reflecting entrapment and presenting to audiences the unnatural confinement of birds in cages, they should be free in the wild. This is asserted through the camera capturing the horror and shock on Blu’s face as he cowers away, terrified by the sights, signalling to audiences that this is unnatural (Fig.11&12). The film uses cages to communicate Blu’s movement to freedom and away from domesticity but also as a vehicle to comment on morality and the illegal bird smuggling Brazil, removing birds from their natural environments. Where the cage is initially presented as a space of safety, it is now a symbol of entrapment. These oppositions are tested throughout the film, disrupting the anthropomorphism and animalisation by way of creating comedy and drama and the birds the film are used as vehicles to make wider comments about society, the human world and morality, in playful and moderate ways.

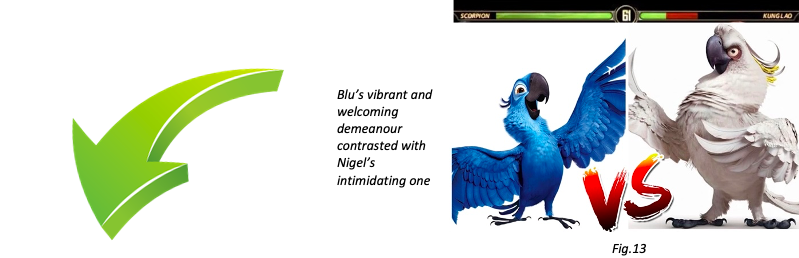

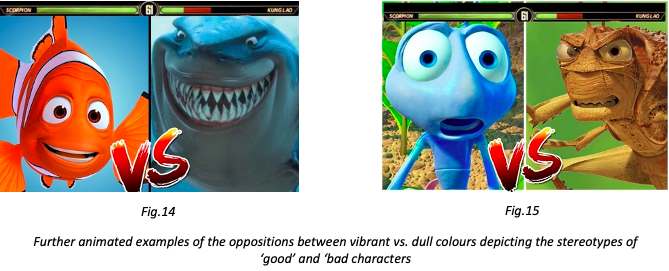

This moral corollary is also presented through the stereotypical use of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ characters. The film animates good animal characters as colourful, intelligent and vibrant in complete contrast to the dull, evil depiction of the ‘baddies’. This is a common trope within the family-film genre and a ‘memorable outcome of such Disney narratives’,[5] especially as younger viewers rely on cues to navigate through the narrative. Blu and Jewel are both Blue Macaws, vibrant in colour and associated with intelligence while Nigel, a damaged Sulphur-crested cockatoo, is characterised as disfigured and unattractive(Fig.13). By conforming to these animated stereotypes, the film encourages audiences to side with these righteous characters, using animal birds as playful vehicles to discuss ideas deeper ideas about morality and wider social issues, through a well-known lens; ‘the victory of good over evil’.[6]

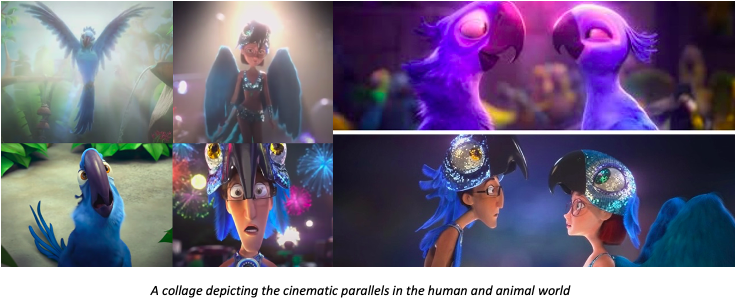

The film tackles ideas of human-animal relationships within the film in two ways; by giving each bird character a human counterpart that reflects their traits and personality but also by mirroring scenes within the human and animal world to relay ideas of shared emotions across species. This is introduced in the film through the playful concept of ‘love at first sight’. When Blu is introduced to Jewel for the first time the camera adopts a high-angle medium shot over Blu, enlarging his eyes and presenting him as enthralled by Jewel’s majestic beauty. The animation style allows Blu’s eyes to open abnormally large as he stares in awe, presenting this idea of ‘love at first sight’. This is paired with a low-angle shot of Jewel, presenting her as a god-like figure as she emerges into the shot. The film utilises slow-motion camera-work at this moment to capture her majestic wings and vibrant colours and the mise-en-scene enhances this through the use of a building musical crescendo and a blurred focus effect, generating a fantastical atmosphere.

This scene draws allusions to the idea of animal courting, where birds use their colourful feathers to attract the opposite sex. The film adapts this stereotypical concept in the animal world to present a recognisable scene, setting up Blu and Jewel’s relationship. The mise-en-scene creates a cinematic pleasure through the use of visual and sound cues, placing an importance on the idea of feeling and emotion in animation film and not just narrative.

This same interaction is presented to us much later in the film, but within the human world between Linda and Túlio. As they dress up as blue macaws in an attempt to sneak into the float parade, the same cinematic scene is directly mirrored. As Túlio sees Linda in the bird outfit he adopts the same facial expressions as Blu and the camera captures his wide eyes and gaping mouth open in shock and awe. The same cinematic pleasures are generated capturing Linda blurred focus effect, a building soundscore and slow-motion to create this same atmosphere of enthrallment and fascination. The film does this to present this idea of love and beauty but in the human world. This intensified realism is generated through sound, visuals and sensations, placing a demand on physical and emotional feeling over narrative importance.

The film chooses to dress Linda Túlio in bird costumes to create a direct parallel to the earlier scene and work as an obvious signal to young audiences. The repetition presents the idea that humans and animals both share mutual emotions of love and attraction. By presenting the concept firstly through animals in an exaggerated playful style, it is easier to understand and so when it happens to humans, these signals are picked up again. The animals are used to translate the ideas of human and animal shared emotions, especially when it comes to love and attraction and audiences are encouraged to share these feelings thanks to the cinematic pleasures generated by the mise-en-scene.

Rio creates a highly pleasurable cinematic experience through its use of intensified realism, vibrant colour palette and playful musical soundscore. Through its animated style and anthropomorphic portrayal of birds, the film is able to cleverly discuss the wild vs. civilised opposition, tackle ideas of morality, and teach audiences about the shared emotions experienced within the animal and human worlds.

References:

[1] Paul, Wells. The Animated Bestiary : Animals, Cartoons, and Culture, Rutgers University Press, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 1-236 pg. 71 <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=413877.> [accessed 2nd January 2022]

[2] Paul, Wells. The Animated Bestiary : Animals, Cartoons, and Culture, Rutgers University Press, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 1-236 pg. 20 <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=413877.> [accessed 2nd January 2022]

[3] Paul, Wells. The Animated Bestiary : Animals, Cartoons, and Culture, Rutgers University Press, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 1-236 pg. 74 <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=413877.> [accessed 2nd January 2022]

[4] Paul, Wells. The Animated Bestiary : Animals, Cartoons, and Culture, Rutgers University Press, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 1-236 pg. 71 <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=413877.> [accessed 2nd January 2022]

[5] Paul, Wells. The Animated Bestiary : Animals, Cartoons, and Culture, Rutgers University Press, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 1-236 pg.75 https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=413877. [accessed 2nd January 2022]

[6] Paul, Wells. The Animated Bestiary : Animals, Cartoons, and Culture, Rutgers University Press, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 1-236 pg.75 https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=413877. [accessed 2nd January 2022]

Bibliography:

Burt, Jonathan. Animals in Film, Reaktion Books, Limited, 2004. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 1-234 <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=449396.> [accessed 28th December 2021]

Molloy, Claire. Popular Media and Animals, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2011. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 1-22, <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=741949.>[accessed 19th December 2021]

Saldanha, Carlos, dir., Rio, (Blue Sky Studios & 20th Century Animation, 2011)

Wells, Paul. The Animated Bestiary : Animals, Cartoons, and Culture, Rutgers University Press, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 1-236 https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=413877. [accessed 2nd January 2022]

Further reading:

Guynup, Sharon, São Paolo Trafficking: Smuggling Brazil’s Wildlife, Mongabay Environment News, 2015. https://news.mongabay.com/2015/10/sao-paolo-trafficking-smuggling-brazils-wildlife/ [accessed 13th January 2022]

Hadley, Sophie, The Illegal Bird Trade in Brazil Is Responsible for Thousands of Bird Deaths, Earth.org – Past, Present, Future, 2021. < https://earth.org/illegal-bird-trade-in-brazil-saffron-finches/ > [accessed 13th January 2022]

Marchuk, Alexandra, Animated Kids Content: Why Does It Appeal to All Ages?, Darvideo Animated Explainer Video Production Company, Animation Studio, 2021, https://darvideo.tv/blog/animated-videos-for-kids/ [accessed 7th January 2022]

Murray, Robin L., and Joseph K. Heumann. That’s All Folks? : Ecocritical Readings of American Animated Features, Nebraska, 2011. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 1-296 <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=915035.> [accessed 7th January 2022]

Hitchcock, Alfred. Hitchcock on Hitchcock, Volume 1 : Selected Writings and Interviews, edited by Sidney Gottlieb, University of California Press, 2014. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 1-386 (specifically Chapter: Technique, Style, and Hitchcock at Work, pp. 261-362)https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=1742944. [accessed 7th January 2022]