Teaching a Teen, Canine Companions, and the First CGI Animal in Movie History

The last Jim Henson release, Labyrinth, a cinema flop but since a cult classic, follows a teenage Jennifer Connelly (Sarah) trying to rescue her baby brother from David Bowie (Jareth) by making her way through a Labyrinth “where everything seems possible and nothing is what it seems.”

Sixteen year old Sarah resents her step-mother and new half-brother, and, annoyed at babysitting duties, the last straw being Toby (Toby Froud) having her teddy bear, she calls upon the Goblin King (Jareth) to “take [him] away, right now.”

Despite being centred around these three human protagonists, the story wouldn’t be possible without the whimsical universe’s animals and creatures. From a worm who says “‘Allo” to Jareth taking the form of an owl to the impact of Sarah’s dog, Merlin, animals are at Labyrinth’s heart, setting up interesting insight into adolescent learning curves and capitalist over-consumption.

For many, Labyrinth conjures nostalgic memories and obsessive fascination (for me, this led to successfully begging my dad to name my much younger brother Toby), immediately demonstrating its impact on its audience’s development; a support as we grow from kids to adults.

From the mind behind Muppets, Fraggle Rock, and The Dark Crystal, Labyrinth is a fantasy adventure. It also blends all the elements movie-makers tell you to avoid: babies, puppets, animals, rock stars… to create an unexpected coming-of-age plot. The labyrinth, while a perfect setting for Henson’s usual weirdness, represents an exploration through adulthood. As Sarah learns to take responsibility and rescue her brother, she encounters characters like Hoggle, a literally two-faced dwarf, and Ludo, an innocent beast who is not as scary as he seems, along the way, allowing the animals to become both a trope and teacher simultaneously.

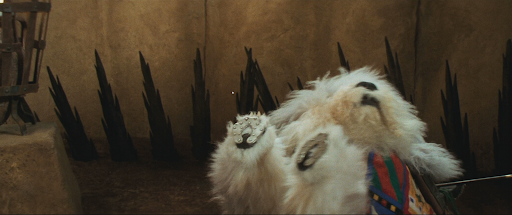

One character who sticks out most is Sir Didymus and his “loyal steed” Ambrosius. While Sir Didymus wears a pirate-like eye patch, blue hat with a yellow feather, green gloves, gold sword and holder, and a knightly red jacket, Ambrosius is equally styled; adorned by a leather saddle, silver stirrups, and a colourful blanket.

Speaking with Empire magazine, Labyrinth’s screenwriter, Terry Jones, recalls; “Jim came round to my house in Camberwell and I remember he couldn’t take his eyes off our dog, which was a long-haired Jack Russell terrier. It eventually became the basis for the knight, Sir Didymus.”

Sir Didymus is a fox-terrier convinced he is also a knight, guarding the bridge across ‘The Bog Of Eternal Stench’. This childishness, evident in Sarah being a teen, is mirrored in Sir Didymus’ lack of understanding. He plays a role without comprehending this power and individuality. As Sarah meets him on her quest, Sir Didymus, having sworn to permit only those with his approval to traverse the bridge, realises, post-Sarah’s inquisition into his vows, that he has the authority to grant permission to anyone that seeks to cross. She seeks his consent to allow her and her party to pass and, initially perplexed, Sir Didymus eventually agrees to Sarah’s request, granting her passage onto the bridge and joining her party.

This scene embodies the similarities between Sarah and Sir Didymus. They are both stuck in a character, Sarah practising for her school’s play and Sir Didymus engrossed in knightly duties, but both lacking insight and making up for it with their costumes and feline companions.

A subtle lesson Sarah learns is overconsumption. While we see her bribe Hoggle with her plastic bracelet, there’s an interesting relationship between the animals and their attempt to be ‘human.’ Ludo is least human-like, he struggles to form sentences and is beastly in appearance, and is not accessorised whereas Sir Didymus, under the impression he is a knight, tied himself to his royal role through his clothes. From the milk bottles on his door to the “horse” shoes we can only assume he put on Ambrosius, it’s apparent these objects help the character to feel less animalistic. Sarah’s bedroom helps to provide further insight, with decor presenting each character as a toy prior to their on-screen appearance. Even his eye patch seems to be part of his people-like costume, shown with two eyes in perfect condition underneath his patch while in toy-form.

According to David R. Burns and Deborah Burns, “In Labyrinth, Henson educates viewers about the illusive qualities of overconsumption and encourages viewers to resist the mass media and contemporary culture’s messages of overconsumption. Through Sarah’s education… Henson reveals the uncomfortable truth that consumer goods fail to provide the fulfilment of genuine human relationships and have a deleterious effect on planetary ecology.”

With tests from The Junk Lady, Sarah begins to see how by hiding in her room full of fantastical, fictional escapes, she has cut herself off from friends and family. For Burns and Burns, “The Junk Lady shirks away from human connection because she has too many discarded consumer items collected on her back.” Perhaps this is a dramatised warning at Sarah’s future. Applying Matt Duncan’s consumerist understandings of Fantastic Mr Fox to Labyrinth, considering Aristotle’s Metaphysics, wherein “each kind of thing,” whether that be a person or a person’s eye, an animal or an animal’s tail, “has its own characteristic function,” places identity and behaviour together. For Sarah, performance and storytelling is where her behaviour lies, leading each object she collects to support this trait.

In the journey of growing up, it is crucial for young individuals to navigate their interests and behaviours. Hannah Arendt discusses how “society will always produce some sort of “communistic fiction,” whose outstanding political characteristic is that it is indeed ruled by an “invisible hand,” namely, by nobody.” This “invisible hand,” akin to the forces shaping societal dynamics, signifies the absence of explicit authority, allowing for self-discovery and individual exploration. Encouraging young people to explore their passions and learn the lessons of moderation mirrors the principles of this “invisible hand,” steering them towards a balanced and informed adulthood.

Just as Sir Didymus uses his trait of a chivalrous nobleman to define him, Sarah, being interested in the fictional, from theatre to toys, is wholly absorbed by this, leading both to be overwhelmed by clothing, appearances and living up to a character placed on them by themselves. Hiding behind these aspects leads to their need for memorabilia: seen in Sarah’s maximalist bedroom and Sir Didymus’ ‘decorated’ jacket.

Now, his Bearded Collie, Ambrosius, is equally as important. It’s interesting to note that in Labyrinth’s opening scene we are introduced to Sarah’s pet dog, Merlin, who is played by the same old English sheepdog as Ambrosius. Referring to the pseudohistory novel The Historia Regum Britanniae (The History of the Kings of Britain), a mediaeval text written by Geoffrey of Monmouth that introduced the legend of King Arthur and “Merlin Ambrosius” the magician, makes clear an intention to tie to the mythological.

It seems ironic that two characters who don’t speak, Merlin and Ambrosius, take their names from such a famous magician. While cowardliness is a shared trait between Merlin and Ambrosius, their shared link to the legendary wizard is their relationships. Ambrosius is treated with affection by Sir Didymus, Merlin is cared for by Sarah, and King Arthur is reliant on the magical Merlin. Each of them are relied upon and considered an ally, to be protected, solidifying the link between Sarah and her labyrinth reflection, Sir Didymus..

While Merlin’s on-screen appearance is short, during that time he allows us to see the ‘fairy tale’ plot being set out, with Sarah’s “wicked step-mother” referring to him as “The Dog!” and sending him to sleep in the garage. Is this treatment the catalyst for the semi-musical movie’s premise? It’s established that her babysitting duties are a weekly occurrence, meaning leaving Merlin in the pouring rain may have been the spark that lit the fire.

While humans take the focus, Sarah as navigating the labyrinth, her brother, Toby, needing to be rescued, and Jareth as controller of the labyrinth and Goblin King, each character would be powerless if not for the animals around them. Not only does Sarah need their directions and teaching-moments, but the Goblin King’s kingdom would not function without its creatures.

As King, obviously Jareth depends on his goblins, but he also relies on his owl alter-ego, just “one of the many manifestations of the Goblin King,” according to the film’s production notes. This owl follows Sarah from the very first scene, beginning with a computer-generated image (CGI) leading us from the opening credits to Sarah and Merlin rehearsing for a play in the park. Despite Jim Henson being known for puppetry and physicality in his creations, the CGI owl “is widely regarded as the first realistic CGI animal to appear on the big screen.” In this opening, Paula Block and Terry Erdmann describe how “the owl glides up into the center of [the] frame. His body acts like a light source, casting a faint illumination on a black floating title.”

The film’s groundbreaking use of photo-realistic computer-generated animals to create 1 of 3 presentations of his owl persona, the other 2 being real and puppet, marked a cinematic milestone. Not only for its experimentation but for allowing Henson’s final contribution to cinema to solidify his creativity and physical theatre through the prevalent feature of puppetry which Henson opted to focus most on outside of this opening sequence, despite these groundbreaking graphics. This allows the film to mark the turning point towards hyper-realistic animation, evidenced by Pixar’s release in the same year: Luxo Jr.

Luxo Jr. is a computer-animated short film directed and written by John Lasseter. It’s two-minute story centres around two desk lamps (one larger known as Luxo Sr., and the smaller, “younger” Luxo Jr.) which shaped their now infamous production logo where the semi-anthropomorphic character is seen hopping across the scene and jumping on the animation companies ‘I’ at the beginning of every Pixar film, making it their primary mascot.

Jareth’s transformation into an owl also serves as a powerful symbol with rich implications. The owl, an enigmatic creature with cultural significance as a mysterious being of the night, aligns with Jareth’s supernatural and elusive nature as the Goblin King, with the choice of an owl, often stereotyped as highly intelligent, drawing parallels to Jareth’s intellect.

In earthly settings, Jareth takes the form of an owl, shown when the owl flaps against her widow before Bowie’s first appearance. Jareth’s recurrent transformation into this creature underscores his ability to manipulate perceptions, adding a layer of psychological complexity to the narrative. Circling back, the owl’s presence at the film’s conclusion, watching through Sarah’s window, leaves a haunting impression, symbolising Jareth’s enduring influence and a lingering sense that Sarah has not entirely overcome his enchantments. This cinematic choice not only showcases technological innovation but also adds depth to the exploration of human-animal dynamics within the fantastical realm of Labyrinth.

Owls, historically connected to the occult, as described by Soni, Ph.D., add an extra layer of mystique to Jareth’s character, underscoring his otherworldly powers. With owls rarely sighted in real-life, this embodiment adds to the feeling of being watched that haunts the film. Jareth is watching her every move in the labyrinth even when he can’t be seen, and, while also taking on disguises, is subtly evident in every corner of his weird universe.

Soni, Ph.D. explains, “The coloration of the owl’s plumage plays a key role in its ability to sit still and blend into the environment, making it nearly invisible to prey.” While owl’s feathers certainly help to keep them warm, their colours also help it blend into nature – with snow owls white colour melting into its snowy habitat whilst darker coloured owls camouflage against trees. His owl form, while the first to appear on screen, is also the last thing we see, watching through her window at the very end – a haunting acknowledgement that Sarah has not defeated him – despite remembering her lines.

Labyrinth is a fantastical tale that goes beyond the central human characters of Sarah, Jareth, and Toby, with interactions with its animals, Sir Didymus, Ambrosius, Merlin, and Owl manifestations, exploring themes of adolescent learning, overconsumption, and the interconnectedness between humans and animals.

Sir Didymus, a fox-terrier convinced he is a knight, mirrors Sarah’s struggle with identity and societal roles. As Labyrinth navigates the complexity of adolescence, it not only imparts valuable lessons about identity and responsibility but also establishes a profound connection between humans and their animal companions. Labyrinth encourages viewers to resist societal messages of excess and prioritise genuine human connections over material possessions, going beyond the surface of a fantasy adventure, using its whimsical creatures and animals to convey timeless messages about self-discovery, responsibility, and the delicate balance between humans and the natural world.

“You have no power over me.”

Suggested further reading:

- Giuffre, E. “Entering the Labyrinth: How Henson and Bowie Created a Musical Fantasy.” In The Music of Fantasy Cinema, Equinox Publishing, 2012, pp. 95-110.

- L.A Banks. “The Hidden Meaning of ‘Labyrinth.’” Geeks, 2017. <https://vocal.media/geeks/the-hidden-meaning-of-labyrinth>

- Richard Lawson. “Why They Can’t Ever Make ‘Labyrinth’ Again.” The Atlantic, April 9, 2013. <https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2013/04/new-labyrinth-doesnt-have-be-bad-thing/316456/>

- Watson, Jeanie. “MARY STEWART’S MERLIN; WORD OF POWER.” Arthurian Interpretations, JSTOR, vol. 1, no. 2, 1987, pp. 70–83.

Bibliography:

Arendt, Hannah. “The Human Condition.” 2nd ed., University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Block, Paula M, and Erdmann, Terry J. “Labyrinth: The Ultimate Visual History.” United States: Insight Editions, 2016.

Burns, David R., and Burns, Deborah. “Anti-Consumerism in Labyrinth.” In The Wider Worlds of Jim Henson: Essays on His Work and Legacy Beyond The Muppet Show and Sesame Street. United States: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers, 2012. pp. 131

Duncan, Matt. “Consumerism, Aristotle and Fantastic Mr Fox.” Film-Philsosophy 19, 2015, pp. 249-69.

Jon O’Brien. “Labyrinth 30th anniversary: 15 things you may not know about the film.” Metro, June 27, 2016. <https://metro.co.uk/2016/06/27/15-things-you-may-not-know-about-labyrinth-5913485/>

Soni, Ph.D., Hiren B. “Owl ‘The Mysterious Bird’.” India: Pencil, June 13, 2022.

Sur, Debadrita. “There are 7 faces of David Bowie mysteriously hidden in the film ‘Labyrinth’.” Far Out Magazine, 28 January 2021. <https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/david-bowie-7-hidden-faces-in-labyrinth-film/>

Williams, Owen. “Labyrinth: the behind-the-scenes history.” Empire Magazine, Issue #272, February 2012. <https://www.empireonline.com/movies/features/labyrinth-movie-history/>