‘In the act of othering, what is projected onto the other is all that must be refused in constructing the identity of the self’[1].

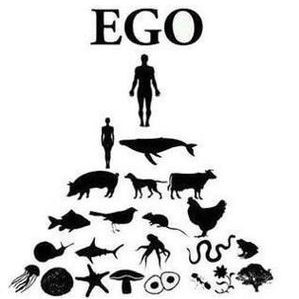

Consequently, establishing a human/animal binary often leads to a hierarchical relationship, highlighting the difference between human and non-human ‘other’. Such binary differences are reminiscent of common tropes in gothic literature, with the degenerate ‘other’, usually a non-human animal, highlighting the beauty and brawn of humanity. However, if the ‘other’ is a corpse, how literally is ‘over my dead body’ taken? Tim Burton’s CorpseBride (2005) therefore uses non-human animals to explore societal convention and anxieties, since animals ‘function as a site for working out or contesting complex anxieties of difference’[2]. Animals, albeit not inherently gothic creatures, operate in the ‘othered’ realm, as legitimised by the human/animal separation and such relegation infers that the animal, as the other, is gothic[3]. Alongside animals, Burton utilises an obscure form of stop-motion animation, and common gothic tropes to explore societal anxieties of Victorian England and how this exploration of human/animal relations presents itself as a didactic text for modern-day consumption.

Figure 1: A pyramid representing Speciesism.

Figure 2: A representative drawing of a gothic double character.

Figure 3: A promotional poster for a production of Frankenstein.

The inspiration for Corpse Bride came from a Nineteenth Century Eastern-European folk tale about a young man who accidentally marries a corpse bride and must fix the situation to return to the land of the living to marry his fiancé.[4] CorpseBride follows this tale closely, yet Burton infuses it with mystery, macabre and a myriad of music and colour, indicative of his style, which takes it from simple myth to animated wonder. Whilst Burton’s style of animation does make it accessible for children, CorpseBride is not to be mistaken as a children film, since the gothic tones and terrorising themes place the film into a subgenre of gothic horror.

Figure 4: Behind the scenes of the creative animation of stop-motion.

The audience settle comfortably into the film, following the whimsical pace of the camera’s movement, floating down like a butterfly into the initial scene where we see the protagonist Victor sketching a butterfly, trapped inside a glass vase. Such an entrapment of an animal by a human invokes the human/animal binary, setting the stage for the ongoing motif throughout the film; the domination and exploitation of animals. However, once finished, Victor carefully liberates the butterfly from its cage. The movement of the camera, and the steady transition between high and low angles mirrors the movement of the butterfly, highlighting its significant role within the story about freedom.

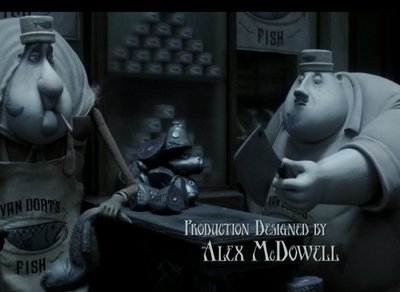

The tracking shot captures the town’s mise-en-scene, from the looming grey buildings, housing the aristocracy, to the clockwork nature if its inhabitants, which represents the normality of the Land-of-the-living. The rhythmic, yet ironically, unanimated fashion of the characters doing their jobs mimic that of clockwork, from the sweeping to the dissecting of fish. The diegetic sound produced by the absurd number of clocks in the window reverberates around the square, disclosing an anxiety around time, or lack thereof, and the steady beat that echoes in our ears is evocative of a heart beating, a reminder that time for the living is finite. This highlights the anxiety around mortality and humans’ inability to control everything. Nonetheless the uncanny feeling produced by stop-motion animation puts the audience on edge since these actions mimic our own lives whereby Burton critiques how soul-destroying capitalism is. The repetitive slog is highlighted by the visually unappealing predictable nature of this scene, alongside the drab colour scheme of greys and milky-whites reflects the austere rigidity of the ‘living’ space, replete with modesty, propriety and custom[5]. This ‘custom’ is conveyed by the characters exclaiming how ‘everything must be perfect, perfect’, disclosing their desire for control. The mise-en-scene, colour & music thus convey the mundanity of life and how limited it is by convention and anxieties to ensure things go ‘according to plan’.

Figure 6: A scene from Hitchcock’s The Birds.

Figure 7: A scene from CorpseBride mirroring the adjacent scene.

In direct comparison to life ‘upstairs’, the Land of the Dead, where the non-human animals reside, seems like dream come true. The audience are greeted with laughter and drinking, and these diegetic sounds invite the audience in, establishing an empathetic reaction. Our understanding of normality is thrown off kilter since the animal in gothic imagery represents otherness, mystery and fear’[6], connotations of corvids and thus seen by the crows lining up in the forest, reminiscent of Hitchcock’s The Birds, as uncontrollable, and therefore dangerous animals, invading the ‘human’ space.

However, Burton subverts the gothic trope of animals as the harmful other and presents them as entertaining beings. The topsy-turvy joy of the spatio-temporal fragmentation[7] in the Land-of-the-Dead counterpoints that of the land-of-the-living, and the uncanny animation of the seemingly dead animals creates a liminality of space, one where no rules apply, dismantling the understanding of normality. The animals of ‘downstairs’ jump into song and despite its sombre title ‘Remains of the day’, dance and cheer in celebration of the inevitability of death and the possibilities of ‘life’ after one pops their clogs. Figure 8: Bonejangles and crew performing The Remains of the day.

The scene is infused with vibrant green, blue and red hues, signifying a natural dynamism and the interpretative jazz and scatting creates a lively and upbeat mood, oozing with fun and is so aesthetically pleasing that becomes infectious for the audience – yes, your foot is tapping away, I know. Human anxieties about animality posits animals as a threat, yet Burton invokes humour and song to transgress the boundary and the dead animals showcase how fun life can be without adherence to custom, implying the real threat to humanity are humans themselves.

The artificially constructed human/animal binary therefore stems from the human fear of losing control, culminating in a powerlessness. By establishing a boundary, humans can exploit the inferior status of the animal, consuming them since animals ‘have been identified as being in the service of the human as a status symbol or for entertainment’[8]. We see this instantaneously, with the quill that Victor uses to draw the butterfly. This feather is a visual synecdoche for the means of production and Victor uses this to draw the butterfly, inadvertently reinforcing the hierarchical relationship. The freedom and liberty connoted with the butterfly represents a transgression of human boundaries which ‘necessitates acts of containment to reinstate the status quo’[9]. By trapping an animal, Victor also traps himself inside the vicious cycle of the human/animal binary.

Figure 10: Mr & Mrs. Everglot and their horse

Figure 11: Victor drawing the captured butterfly

Figure 12: The fish being chopped up.

Furthermore, the dead fish with their heads lopped off convey human violence exerted over animals culminating in Mrs.VanDort wearing a dead fox wrapped around her neck, profiting from their business. Dead and trapped animals thus symbolise the very power humans have over them. Nonetheless, if animals become unconsumable, then they are portrayed as possessing an ‘uncontainable wildness’[10] which results in their monstrosity, seen again in the crows. Consequently, this ‘monstrosity is only to affirm the human’[11] and the power which they possess, quite literally, over the animal. On this premise, the dead, as the other, cannot be consumed and thus posit a threat to boundaries as ‘harbingers of category crisis’[12], yet through Burton’s novel gothic humour and animation, challenges this anthropocentric stance.

Figure 13: Victor amongst the dead juxtaposing his flesh with their missing skin, eyes and intact body.

Burton’s use of stop-motion has an inherent disposition for horror and the gothic, since animating inanimate objects is uncannily visceral as it transgresses our own boundaries. The dead are friendly and compassionate towards each other, conveyed by the jovial mood in ‘Remains of the day’, but also are scared and can feel pain, as articulated by Emily. The capacity for emotion resonates with the audience, establishing an empathetic response, overruling their ascribed ‘otherness’ which dismantles the human/animal binary. Furthermore, the trans-corporeal nature of the dead, possessing bodies with holes, missing limbs and eyes, and splitting in half, present them as agents of transgression, while their defilement of borders[13] is showcased in their ability to, eye-poppingly transcend bodily limit.

Figure 14: The maggot popping out of Emily’s eye socket.

Figure 15: The dead man splitting in half.

Ironically, these liminal properties are utilised to gloss over [the] monstrous nature through humour[14]. Emily, as a rotting corpse, ends up hosting a humorous maggot, which spontaneously pops out of her eye. This sharp-witted inconvenience, which salivates at the thought of food despite being unable to do so, infuses scenes with hilarity, overlooking her monstrous nature as a corpse. Furthermore, instead of a binary, the two form a symbiotic relationship, with the maggot feeding off her flesh whilst Emily receives friendship and advice. The absurdity of the scene enables the audience to look past the ugliness of abnormality and presents the beauty of relationships based on equality, not hierarchy. This symbiotic relationship is portrayed elsewhere, with the ‘head’ waiter moving around via the help of cockroaches and the ownerless limbs in the ‘2nd hand shoppe’ help Emily find Victor after he runs away. The compassionate nature, infused with obscurity and humour, fosters relationships which build a healthy and prosperous society which don’t rely on the subjugation of animals and Burton takes an EcoGothic approach to showcase how if we work with nature, not over it, we too can have a prosperous society.

Figure 16: The ‘head’ waiter aided by insects.

Figure 17: The ownerless hands helping Emily find Victor.

An EcoGothic approach takes a non-anthropocentric position to reconsider the construction of monstrosity and fear. Ecofeminism, in providing a theoretical base, exposes interlocking androcentric and anthropocentric hierarchies and thus examines the construction of the Gothic body, exploring how it can be seen as a site of both environmental and species identity[15]. Consequently Burton, evoking the gothic trope of the double, uses the dead animals to contest Victorian ideals about femininity whilst challenging anthropocentric views of animals. The patriarchal norms, insidiously rooted in Victorian society are rife in CorpseBride, visualised by the arranged marriage, a monetary transaction to keep the Everglots afloat, down to the very corset Victoria wears, literally constraining her movement and breath. These instruments subordinate women, ensuring she does not retaliate and cross the boundary which maintains the monopoly of power in the male realm. Figure 18: Victoria wearing a corset.

In direct comparison, the othered Emily is unlimited via her gothic body, enabling her to challenge these societal conventions. After Victor comes to apologise to Emily for lying, they share a piano duet and Emily has so much enthusiasm that her hand, quite literally, runs away from her. The hand, which continues to play by itself, then runs onto Victor’s arm and although not a piano, the notes are still heard, a high-pitched twinkle creating a hopeful mood, highlighting the possibilities of the future. Returning to the diegetic duet, with deep dark chords and light whimsical melodies represents Emily’s experience with love, loss and pain yet it is through the liminality of her body, which enables the music to represent her agency and autonomy as an independent woman.

When she is dancing in the forest with Victor, mirroring the whimsical movements of the butterfly at the start, she breaks a leg, and falls over. During both scenes she pardons her ‘enthusiasm’, looking away with bashful eyes and embarrassment about her unruly body, yet it is this ability to transcend her body, and her unruliness ‘performs the ultimate reclamation of the self and the celebration of the female liberation’[16]. Her liminality renders her a figure of ambivalence, unwilling to be confined to one place, which culminates in her bringing justice to her murderer, Lord Barkis Bittern. Barkis embodies the patriarchy, marrying for wealth only, as he exclaims to Victoria ‘your dowry. It’s my right!’. His insatiable greed, wolf-like appearance with sharp hair and a long coat tail, and name which includes ‘bark’ and ‘bit’ convey him as a menace and threat to society. In the penultimate scene, Barkis attempts to kill Victor, yet Emily intervenes and takes the brunt of Barkis’ sword, the same sword that killed her. Whilst her physical retaliation to Barkis represents her agency, this move ideologically dismantles the foundations of patriarchy. Emily’s liberation from the vicious cycle of patriarchal norms and death culminates in her finding happiness, represented as her disintegrating into a myriad of butterflies, with blue connoting serenity and stability, which inextricably coincides with the disintegration of a human/animal binary.

Figure21:Blue butterflies surrounding Mary Poppins

Figure 22: Emily disintegrating into butterflies.

Figure 23: Blue butterflies surrounding Pocahontas.

CorpseBride, woven together with exceptional cinematography, visual and sound design, is a tale about difference, and the sacrifices one makes to establish freedom, conveying the importance in challenging normality and the binaries produced to legitimise it. Burton’s use of the gothic tropes, emphasised by his forte stop-motion, enabled him to present his jazzy rendition of the repercussions of challenging binaries, and the use of music, as a universal language, fused the two worlds together. The cyclical nature of the film, starting and ending with a butterfly presents the notion that without transgression, there can be no change, hence boundaries are there to be broken, and if a folk tale can be given a modern twist, then modern-day binaries can be updated or overcome, transcending binaries and establishing a world free of constraints and presenting a more colourful future for us all.

[1] Rebecca Lloyd, ‘Dead Pets Society’ in Tim Burtons Bodies, ed. By Stella Hockenhull & Frances Pheasant-Kelly ( Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021), pp.81-93 (p.82).

[2] Wolves, werewolves and the Gothic, ed. Robert McKay & John Miller (Cardiff: University of Wales Press,2017) p.12.

[3] Rebecca Lloyd, ‘Dead Pets Society’ in Tim Burtons Bodies, ed. By Stella Hockenhull & Frances Pheasant-Kelly ( Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021), pp.81-93 (p.81).

[4] Emily Mantel, ‘Agreeing to be a burton body’ in Tim Burtons Bodies, ed. by Stella Hockenhull & Frances Pheasant-Kelly ( Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021) pp.27-41(p.36).

[5] Christopher Holliday, ‘Tim Burton’s Unruly Animation’ in Tim Burtons Bodies, ed. By Stella Hockenhull & Frances Pheasant-Kelly (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021) pp. 42-53 (p.48).

[6] Rebecca Lloyd, ‘Dead Pets Society’ in Tim Burtons Bodies, ed. By Stella Hockenhull & Frances Pheasant-Kelly ( Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021), pp.81-93 (p.84)

[7] Christopher Holliday, ‘Tim Burton’s Unruly Animation’ in Tim Burtons Bodies, ed. By Stella Hockenhull & Frances Pheasant-Kelly (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021) pp. 42-53 (p.48).

[8] Rebecca Lloyd, ‘Dead Pets Society’ in Tim Burtons Bodies, ed. By Stella Hockenhull & Frances Pheasant-Kelly ( Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021), pp.81-93 (p.82).

[9] Ibid., p.82.

[10]Ibid., p.82.

[11] Patricia MacCormack, ‘Posthuman Teratology’ in Ashgate research companion to monsters and monstrosity, ed. By Asa S.Mittman & Peter J.Dendle (New York: Routledge, 2016) pp.293-310(p. 293).

[12] Dana Oswald, ‘Monstrous Gender: Geographies of Ambiguity’ in Ashgate research companion to monsters and monstrosity, ed. By Asa S.Mittman & Peter J.Dendle (New York: Routledge, 2016) pp. 343-364 (p.343).

[13] Elif Boyacioglu, ‘Corpse Bride: Animation, Animated Corpses and the Gothic’ in Tim Burtons Bodies, ed. By Stella Hockenhull & Frances Pheasant-Kelly ( Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021), pp.54-68 (p.56).

[14] Ibid., p.62.

[15] David Del Principe, ‘The EcoGothic in the long 19thC’, Gothic studies, 16.1(2014), 1-8 (p.2)

[16] Christopher Holliday, ‘Tim Burton’s Unruly Animation’ in Tim Burtons Bodies, ed. By Stella Hockenhull & Frances Pheasant-Kelly (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021) pp. 42-53 (p.45).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Del Principe.D, ‘The EcoGothic in the long 19thC’, Gothic studies, 16.1(2014), 1-8.

Edmundon, M & Heholt, R, Gothic Animals: Uncanny Otherness and the Animal With-Out (Switzerland: Palgrave macmillan, 2020).

Hockenhull, S, & Pheasant-Kelly, F, Tim Burtons Bodies (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021).

Kavka.M, ‘The Gothic on Screen’, in The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction, ed. By Hogle, J.E (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

McKay, R. & Miller.J, Wolves, Werewolves and the Gothic (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2017).

Mittman, A.S. & Dendle, P.J, Ashgate research companion to monsters and monstrosity (New York: Routledge, 2016)

Spadoni.R, Uncanny Bodies: The coming of Sound Film and the Origins of the Horror Genre (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2007).