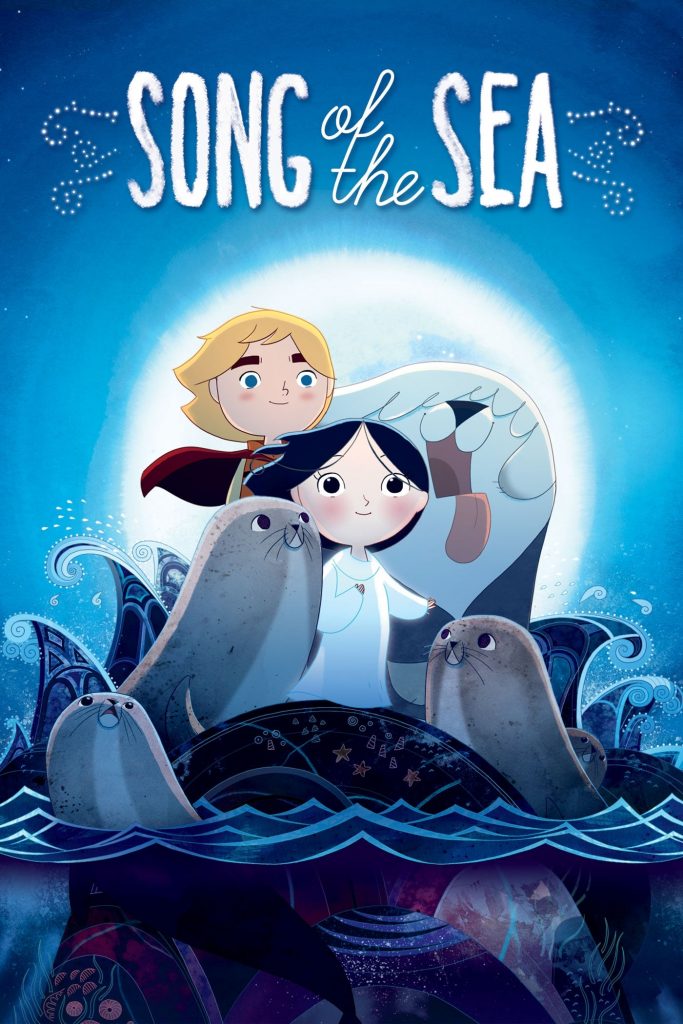

Song of the Sea is full of magic, mystery and mayhem. Ben, a ten year old Irish boy, discovers that his mute sister Saoirse is a selkie. After Saoirse’s true nature is revealed, her father, blinded by fear, retaliates and hides the coat that enables her to transform. This separation causes Saoirse to fall ill. She travels through Irish countryside and city, alongside Ben, in order to find her voice. This will, in turn save the fairies from the reaches of Macha, the evil owl witch from Celtic legend.

Blaming her for the loss of his mother seen at the beginning of the film, Ben treats Saoirse harshly. It is clear that he favours the company of his giant sheepdog, Cú. However, after seeing the detrimental effects of Macha first hand, he comes to realise that the love and affection he shows towards Cú is the key to guiding Macha back towards the light, and helping Saoirse find her voice. He recognises that a mutual understanding between animals and humans is crucial for saving the petrified fairies, and attempts to pass this knowledge on to his father.

Sympathy and softness, themes that run throughout this film, are enhanced by the use of style. They are feelings enriched by the hand-drawn animation of the film, which creates depth and layers. The use of watercolour paint, and avoidance of harsh or bright colours, can be linked back to the sea. A fully immersive experience for the audience is created – even in the dull and subdued cityscapes depicted in the film, colour use is organic, and therefore reminiscent of the natural world. Alongside this, the gentle folk music of the film helps to ease the audience into this environment. Aggression, even in style, is evaded at all costs.

Scenes throughout the film promote a mutual understanding between the animal and the human characters, displaying a healthy balance between the two worlds. Interchangeability between human and animal forms (for example, Saoirse’s ability to transform into a seal) is used to convey this; similarity between the two is depicted in a positive light. Character environments are important contributors to these parallels. The first time that Saoirse uses her selkie coat, she wanders down to the shoreline to swim and the beach lies in darkness.

The murky black and blue colours of this scene, along with the foliage, are reminiscent of the sea floor. Even the boulders in the background, situated around the borders of the frame, look similar to that of seals – they feature the same mottled pattern that is seen on real blubber. A direct comparison can also be made between the distribution and grouping of the rocks behind Saoirse, and the seals that lie in front of her, even if the latter do appear much smaller. The similarities in design between the two settings insinuate that perhaps the two are not so different after all, and that Saoirse can happily belong in both. Her world and that of the seals are linked. As she swims out and away from shore, she situates herself between the two realms, and demonstrates her link between the two.

Figure 2 – Seal in Plockton harbour

Figure 3 – Saoirse on the beach

Figure 4 – Zoom of Figure 3

Saoirse’s interactions with the seals helps to support the notion of interchangeability between humans and animals. When Saoirse approaches them, the group of seals begins to bark at her, happy at her arrival. They smile and she imitates them in reply, splashing the water as she does so. This call and response between the two groups is the first time that we hear any significant sound from Saoirse that vaguely resembles talking. Her audience of seals is significant for this moment as it is clear that she feels more comfortable around them than her own family. The communication between the two groups shows likeability and similarity.

After this, the seals take her on a dive below the surface of the water. Other animals, that reside below, acknowledge her presence in their environment by responding to her movements on screen. As Saoirse swims across the frame, now in seal form, the larger jellyfish grow in size to fill more of the screen. Their increased proximity to her suggests intrigue and acceptance. The same occurs with the smaller jellyfish, which rise up and over the path that Saoirse takes across the frame as she swims. We can see that throughout this underwater scene, Saoirse is interacted and connected with by the other animals.

Figure 5 – Saoirse and the jellyfish

Figure 6 – Saoirse and the jellyfish

Figure 7 – Smaller jellyfish

Figure 8 – Smaller jellyfish

Figure 9 – Smaller jellyfish

However, her final jump out of the water, which transforms her (if only briefly) back into a human, is a reminder to the viewer that she is the tie between both worlds. She can travel between the two at ease. This notion is also seen in the next frame, which depicts Cú (Ben’s pet dog) asleep in bed next to him. Cú here plays the part of human as he provides emotional support for Ben – a role that Saoirse would normally undertake. His animal status and Saoirse’s human status have been inverted, a confirmation that the two worlds can co-exist synonymously.

Figure 10 – Cu and Ben

Figure 11 – Saoirse and Ben

Figure 12 – Saoirse’s resurfacing

This prosperity amongst animal habitats promotes environmental respect and kindness. Not only this, but an excess of human control, which leads to an abuse of these habitats is shown in order to raise awareness for the audience. We see this particularly as the two siblings get off the bus and enter the depths of the forest. As Saoirse walks ahead of Ben and drags him along, claiming agency for herself, peaceful animal family units are seen. This is something that Ben and Saoirse are themselves in search of. In this way, the animals claim a space for themselves – an aspect of life that provides them with the upper hand against the human characters, who are used to control. Their harmony and peace are shown via emotional and uplifting music, a shift from the slower and more sorrowful ballads that play beforehand.

Figure 13 – Fox habitat

The presence of birds briefly shown in the scene frightens Ben, causing him to cling to a tree. Birds provoke this reaction throughout the film due to the control of Macha, the villainous owl witch. When the siblings reach a forest clearing, things become gloomier. Scattered with petrified fairies and human litter, the clearing could resemble that of a graveyard. The blackbird seen in the foreground of the frame remains a visible threat to the children, and reminds the audience of their presence in the film. When he hears rustling in the shrubbery, Ben becomes petrified and hides behind a broken television. His statement of ‘Please don’t let it be Macha’ shows that animals throughout this scene have maintained their own agency. Their dominance and ability to provoke emotions (control of which Macha displays later on) is depicted as a negative power via the children’s response.

Figure 14 – Blackbirds

Figure 15 – Ben’s scared response

The surrounding environment plays a subtle role in dispelling human dominance. This scene depicts a failing habitat – one that has been ruined by the presence of people. Litter lines the outskirts of the clearing, such as an abandoned mattress and bin bags. This resembles that of fly tipping, something that occurs often clandestinely, particularly in forests such as this one. The Lake District in the UK, for example, is becoming more frequently abused by tourists who leave items such as tents to slowly rot, damaging the environment.[1] In this scene, Saoirse kicks a can out of frustration, perhaps aware of the damage occurring. Ben replies with ‘We’re not lost’. His statement could be applied to the rest of society, as he maintains hope that the degradation is not irreversible. He insinuates that perhaps not everyone contributes the vandalism of the environment.

Figure 16 – The forest clearing

Figure 17 – Litter in Thirlmere, The Lake District

Cú’s entry into the scene provides him with agency, and promotes an attitude towards animals and their habitats that should be adopted by those of society who do litter. He not only demands attention from the characters and the audience, by bounding across the screen and filling the frame, but also appears as the hero that provides catharsis. His presence resolves the darkness that the siblings experienced earlier. Ben then takes the lead off Saoirse and attaches it to Cú instead. This is important as it highlights Saoirse’s newfound freedom and again reminds the viewer that the two characters are interchangeable – their similarity, along with the kindness shown to Cú, has saved the children from disaster.

Glorification of animals is seen elsewhere in the film, and Cú is again a character that represents collaboration. After they have freed Macha from her own control, the children require a hero to assist them on their journey home. Imbued with a little help from Macha’s magic, Cú comes to their aid. Macha directly addresses him, just as Ben does throughout the film, saying:

‘You are a brave and loyal dog’.

He whines in reply, a similar conversation of call and response that Saoirse previously experienced with the seals. The behaviour in these two groups can be compared. For example, the dogs surround Cú, embracing and enveloping him. When Saoirse first swims, she experiences a similar response as the seals welcome her to swim. Interactions such as these ones show that wild animals are happy to connect with humans.

The dogs that Macha releases are the dogs of ‘the giant Mac Lir’, a photo of which we see in the opening scene of the film, when Cú says ‘They’re best friends, like us’. By placing reminders of this relationship in both the beginning and the end of the film, an emphasis on animal and human partnership is created. This is seen in Irish mythology, which the film is centred around. Mac Lir’s dogs are reminiscent of ‘Bran’ and ‘Sceolang’, the best friends and warrior dogs of Fionn mac Cumhaill, a myth that highlights animal loyalty.[2] Art based on this story depicts Fionn and the two dogs stood side by side, such as Lynn Kirkham’s sculpture in the Irish county of Kildare.[3] This composition is also used, when both Cú and Mac Lir interact with the dogs. The importance of the proximal relationship between dog and man is repeated via this image.

Figure 18 – Lynn Kirkham sculpture

Figure 19 – Cu and Saoirse alongside the dogs

Figure 20 – Mac Lir alongside the dogs

Cú’s actions help to depict his character as heroic and valorous. Ben’s insistence to ‘Go as quick as you can’ could be compared to a similar occurrence in the film Tangled, where Flynn tells his horse Maximus: ‘Ride as fast as you can’.[4] Both instances exhibit a trust in animal power and friendship, and a knowledge that they can help the protagonists on their quests. Cú’s comparison to a stallion could also be seen in the use of diegetic sound. As he carries the children home, the sound of his paws hitting the ground can be faintly heard, a sound reminiscent of horses hooves. Overall in this scene, Cú displays a positive reaction to his role, shown in a close up frame of his lolling tongue. His enjoyment shows that human understanding of, even dependence upon, animals is something to be praised.

Overall, Ben’s character slowly develops an appreciation for wild animals, instead of just domesticated ones like Cú. This is shown through his steadily improving relationship with Saoirse and his determination to save her and the fairies. This story tells a narrative that provides animals with agency and freedom, and a story which depicts humans learning the value of this liberation. This is done via the depiction of rich animal habitats, juxtaposed with environments tainted by human pollution and destruction. In this way, Song of the Sea suggests that habitats should be preserved and respected, and animals likewise.

This is why the film depicts human characters that are happy to progress and learn in order to develop a happy and respectful relationship with animals. Evidence of this progression is shown particularly towards the end, as Saoirse is given the option to become a selkie for good. Similar to the story of How to Train Your Dragon, it is her choice to stay that exhibits her loyalty. [6] Both films show that it is best earned through the application of love and affection, instead of forced human dominance and control.

References

[1] n.a, ‘Lake District abandoned campsite shows ‘sheer disrespect’, BBC News, 29 March 2021, <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cumbria-56562031> [accessed 18 January 2023]

[2] Eibhlin O’Neill, ‘Bran and Sceolan – The Loyal Hounds of Irish Legendary Warrior Fionn mac Cumhaill’, Transceltic, 2016 <https://www.transceltic.com/irish/bran-and-sceolan-loyal-hounds-of-irish-legendary-warrior-fionn-mac-cumhaill> [accessed 18 January 2023]

[3] Kirkham, Lynne, The GreenMantle, <https://www.lynnkirkham.net/> [accessed 18 January 2023]

[4] Tangled, dir. by. Nathan Greno and Byron Howard (Walt Disney Studio Motion Pictures: 2010) <https://www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/movies/tangled/3V3ALy4SHStq> [accessed 18 January 2023]

[6] How to Train Your Dragon, dir. by. Chris Sanders and Dean DeBlois (Paramount Pictures: 2010)

Bibliography

n.a, ‘Lake District abandoned campsite shows ‘sheer disrespect’, BBC News, 29 March 2021, <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cumbria-56562031> [accessed 18 January 2023]

O’Neill, Eibhlin, ‘Bran and Sceolan – The Loyal Hounds of Irish Legendary Warrior Fionn mac Cumhaill’, Transceltic, 2016 <https://www.transceltic.com/irish/bran-and-sceolan-loyal-hounds-of-irish-legendary-warrior-fionn-mac-cumhaill> [accessed 18 January 2023]

Kirkham, Lynne, The GreenMantle, <https://www.lynnkirkham.net/> [accessed 18 January 2023]

Filmography

Moore, Tomm, dir., Song of the Sea (StudioCanal: 2014)

Greno, Nathan and Howard, Byron, dir., Tangled (Walt Disney Studio Motion Pictures: 2010) <https://www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/movies/tangled/3V3ALy4SHStq> [accessed 18 January 2023]

Sanders, Chris and DeBlois, Dean, dir., How to Train Your Dragon (Paramount Pictures: 2010)

Further Reading

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion, 2002)

Turner, Mark, ‘The Origin of Selkies’, Journal of consciousness studies, 11.5, (2004), pp. 90-115

Tekin Gülüm, Burcu, ‘Female Chants from the Past: Celtic Myths in Tomm Moore’s Song of the Sea’, The European Legacy, toward new paradigms, 26.3-4 (2021), 257-269 <https://doi.org/10.1080/10848770.2021.1891666>

Ellis, Peter Beresford, A Dictionary of Irish Mythology (London: Constable, 1987)

Ratelle, Amy, Animality and Children’s Literature and Film, 1st edition (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015)