In the opening scenes of Todd Solondz’s Wiener-Dog, we see the unnamed titular character in a very recognisable form of cage as she waits her collection from an animal shelter. After having been killed by a passing lorry in the film’s climax, Wiener-Dog’s taxidermied body is placed in a glass box and becomes part of an art exhibition. Through this alternate, yet repeated, form of entrapment Weiner-Dog’s bitter truth is revealed. The artificial space that the animal inhabits at both the beginning and end of the film is in fact continuous and was never once escaped throughout the film’s duration.

John Berger argues that human language and expression relies on animal metaphor, as he identifies ‘the universal use of animal signs for charting the experience of the world’. [1] Weiner-Dog reflects this premise as the animal is used as a prop by Solondz to transmit the four different narrative pathways of his film’s human characters.

This anthology form reflects the unusually frequent presence of animals within the para – genre that is multi-narrative films or “hypernarratives”, seen in both independent films such as Wiener-Dog and more financially successful outputs such as Steven Spielberg’s War Horse (2011). The significant role of multiple narratives in animal representation is not restricted to film only but is apparent in literature also, for example Anna Sewell’s 1877 novel Black Beauty. The use of this mode allows for numerous encounters with the same animal yet through different subjects, therefore allowing for the construction of various human experiences and identities through repeated exposure with the non-human. In her work When Species Meet, Donna Haraway expands this idea further as she considers the notion of ‘contact zones’ in terms of ecological intersection, exploring how ‘subjects are constituted in and by their relations to each other’. [2] Specifically, within Wiener Dog it is the relationship with the animal as a form of companion that allows Solondz’s characters to shape their conceptions of self through the master/subordinate lens that is implicit in pet-keeping.

Wiener-Dog is depicted as more of an object than a subject, disavowed of any agency and with no reference to or exploration of her clear animality. As she is passed from family to family and the film becomes an anthology of various human experiences, Wiener-Dog is subsequently denied any true tangible presence outside of her role as a symbol that allows for these experiences to be depicted on screen.

The glass box in which Wiener-Dog’s dead body is confined thus becomes a subversive reflection of the film camera itself. Both attempt to portray life in something which is essentially lifeless. Just as Wiener-Dog’s stuffed body can never replicate the essence of any living presence or sense of being, so can Solondz’s camera never provide the animal with any power to exist outside of the human. She has no chronology or history of her own and is a tabula rasa on which human existence can be mapped.

Indeed, it is somewhat comical that within her glass cage (see fig.2), Weiner-Dog’s shadow is double the size of her body and occupies the vast proportion of the space. In an almost meta revelation, the film thus recognises its own treatment of the animal body. It is not the body or even the animal that is important, rather, it is what this body can potentially represent and what it will allow for. It is the shadow; the murky space of hidden possibilities, potential meanings and ability for narrative progressions that is significant. It is the shadow as a visual indicator of the animal body as an empty floating signifier.

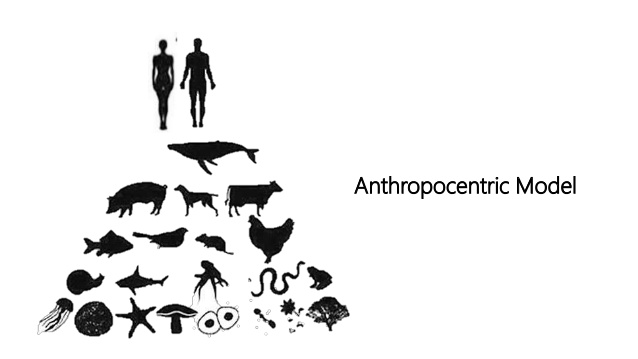

Dead and mummified, Weiner – Dog is disembodied from both her own physicality and the space that surrounds her as she seemingly hovers, or floats, above the glass box and white wall that enclose her body. All animality remains erased, a process that began with her first appearance on screen. Both John Berger and Akira Lippit argue for the decline of living animality within the 20th and 21st Century. However, whereas Berger ascribes this to the rise of modernity and capitalism, Lippit places this loss within a post-modern scenescape that is characterised ‘by the disappearance of wildlife from humanity’s habitat and by the reappearance of the same in humanity’s reflections on itself’ [3] – new media such as films, photography and radio. Crucially, these reflections are created by the human and privilege an anthropocentric discourse, reducing the animal to an ‘Other’ in which humanity can be measured against and contrasted with. For, Lippit the animal existence now exists spectrally, receding into human consumption against a backdrop of increasing environmental destruction. Within her cage and the museum space, Weiner-Dog’s stuffed body becomes an image to absorb and devour, a product of capitalism in which the audience imagines her body as divulging something intrinsic about themselves, and subconsciously disregarding the physical being that once lived. To be a signifier, a metaphor for the human, it is essential that all living animality is left behind – the body cannot be both if anthropocentric meaning is to be privileged.

As the camera slowly zooms out from the shot Wiener-Dog’s head slowly turns, and she lets out two recorded barks. As part of the exhibition, her body has been grotesquely mechanised. Perhaps then, she is not dead? Perhaps, she exists in between life and death, always trapped in this space of signs and symbols? No, Wiener-Dog is not dead, and the audience will see her again. Not in this form of course. She may be a cat, or a giraffe, or a goldfish flushed down the toilet, but her purpose remains the same. Always revealing and never being. Yes, we will see her again

[1] John Berger, ‘Why Look at Animals?’, in Why Look at Animals? (London: Penguin, 2009), pp. 12 – 37 (p.17).

[2] Donna Haraway, When Species Meet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2007), p. 216.

[3] Akira Lippit, Electric Animal: Toward a Rhetoric of Wildlife (London: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), pp. 2 – 3.