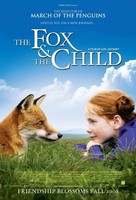

Luc Jacquet’s The Fox and the Child depicts an unnamed girl (Bertille Noël-Bruneau) exploring the French countryside and following its animal inhabitants. She develops an obsession with the titular fox and it becomes more trusting, but the girl disastrously oversteps the boundary and attempts to make the wild animal her pet. The film is interested in binaries of human/animal, wild/captive, and children/adults.

In one scene, the borders between the girl’s world and the fox’s is rigidly defined. The pair are sat on a cliff, their backs turned to the camera, facing the valley below, where the girl’s house is situated. The day is ending and the girl must leave the forest. This is signified as the camera moves forward showing less and less of the forest until the human world fills the frame. The cliff clearly divides the two distinct realms, literalising the frustrating boundary which separates humans and animals, or specifically, separates the girl and the fox. Jacquet aurally exemplifies the blurring of habitats through non-diegetic sound, overlaying birdsong and ringing bells. The girl is eager to invite the fox into her environment, reassuring it not to ‘be afraid… this is where I live with my parents’. This is the closest interaction the audience has with her parents, suggesting the border between animal and adult is greater than animal and child. This is also implied by the pair’s similarities: their mutual fondness for adventure and their ginger hair/fur. The film is typical of literary animal-child friendships; children are afforded a privileged connection with animals, owing to their association with imaginative possibility. They sit side-by-side, seemingly united, but the cliff represents their unfortunate division.

The girl points at her house and the camera’s focus shifts to the obediently observing fox, encouraging the audience to focus on the animal for the rest of the scene. The fox spots the girl’s dog in the valley below, and the camera focuses on the fox’s snout smelling this new animal. The dog, like the girl’s parents, is a part of the human world, exemplified by a distant camera shot. The introduction of the domestic adds contrast, highlighting that although the girl and the fox are exceptionally close, a degree of separation remains. The girl is suddenly called to leave (‘dinner time!’) and the audience remains with the fox’s perspective, watching the girl disappear home. Sad music begins to play as the fox jealously watches the girl greet her dog. The scene concludes with the lone, mournful fox curled up, romantically silhouetted by the setting sun, their encounter over. By day they can play, but at night they must separate: their relationship can never be totally boundaryless. Here, this realisation is treated with sad frustration, but the boundary is eventually accepted by the film’s ending; the tale is re-presented as an oral story told by the girl (now grown) to her future children. The epilogue confirms that the forest is a pastoral space reserved for childhood exploration.