Oh great! A dog wants me to go to St. Petersburg.

Anastasia. 1997.

An adventure with strangers and a new puppy!

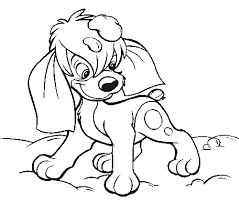

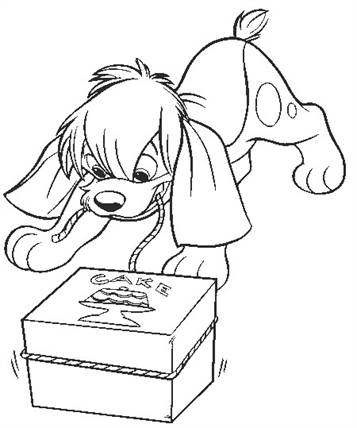

Twentieth Century Fox’s whimsically animated Anastasia follows an orphaned Russian princess, who befriends a scruffy puppy, Pooka. The real journey begins once Pooka is introduced, winning the audience’s heart with his doe eyed, emotive expressions and enthusiastic barking. Their sudden and spontaneous meeting/reunion and eventual friendship emphasises the human and animal bond, whilst becoming an integral aspect of the film. Specifically, the pet acting as a guiding and comforting force for their human.

This romanticised, dream-like retelling of the real, last surviving Romanov child, Franzsiska Schanzkowska perfectly depicts the comforting fantasy children’s animation provides. Although inaccurate to history, the film achieves its purpose with its musical storytelling as it allows the viewer to get lost with Anya and Pooka whilst rediscovering memories and falling in love. Bluth and Goldman fill the screen with imaginative, softly coloured scenes, creating an atmosphere to indulge in.

Anastasia is a musical fantasy film, vibrant in its technicolour and entrancing in its fairy-tale fitting soundtrack. We are first met with a colourful and lively ballroom, filled with pretty flowing dresses and seamless dancing. The use of a romantic purple and pink colour palette paired with diegetic twinkling piano romanticises Anya’s story in a fitting manner for children animation. The destination being dreamy Paris, where romance blooms and which every heart yearns for, is the perfect setting for Anya and Dmitri’s happy ending. We see a smooth transition in the frames from drab browns to rich golds as Anastasia and Pooka progress on their journey back home.

Figure 3. Anastia’s memory resurfacing.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Figure 8

Figure 9.

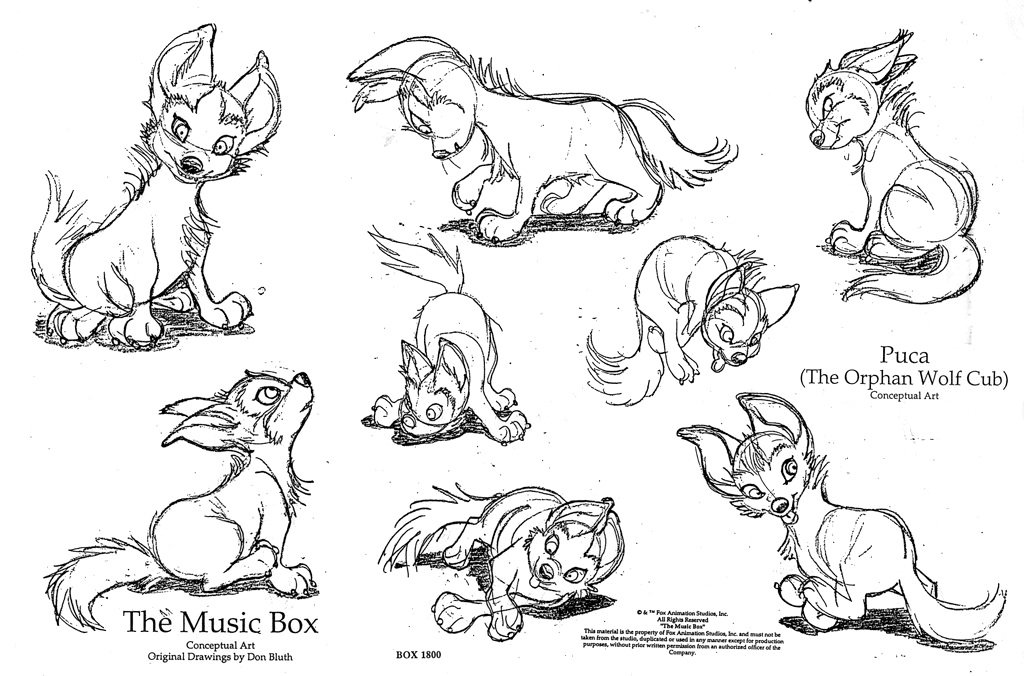

As Kuhn and Westwell define in A Dictionary of Film Studies, aesthetic cinema emphasises viewing “value in terms of enjoyment, pleasure, or emotional stimulation.”[1] This is encapsulated in the animation of Pooka. His adorable appearance and infectious energy create the perfect, lovable animal sidekick for a lost princess.

Figure 10.

Figure 11.

Figure 12.

Figure 13.

Figure 14.

In most children films, animals are central figures. Whether they are domestic pets or magical creatures, they become the dominating character alongside their human companion. Animation allows for an impactful portrayal of human animal bonds that transgress realistic and conventional relationships between human and pet. As Marcus Bullock states, “with animation a lot can be left to doubt,”[2] therefore, “predominantly these animated films are meant for children.”[3] Pooka is a realistic dog, expect for his Disney-like expressive animated face, whereas this description aptly applies to Bartok, Rasputin’s albino bat sidekick. Bartok opposes Pooka visually and narratively, which we will get to.

Figure 15. Lilo & Stitch.

Figure 16. Ariel & Sebastian.

Figure 17. Jasmine & Rajah.

Figure 18. Pinocchio & Figaro.

Figure 19. Mowgli & Baloo.

Figure 20. Rapunzel & Pascal.

The genre of animation paints animals as the focal points in the storyline, and although Pooka does not steal Anya’s spotlight, he is unmissable and hard to forget. The viewers are first introduced to him when Anya is deliberating going to Paris figure out the meaning of her necklace’s inscription, and she desperately asks for a sign. Pooka immediately appears from out of nowhere, the frame captures Pooka and Anya playing tug-of-war with Anya’s scarf amongst the sparkling, snowy backdrop. After playfully struggling with Pooka, Anya trips and accepts this random dog as her sign, “oh great, a dog wants me to go to St. Petersburg.”[4] To cite Bullock again, “animals may not choose as we do, and cannot change their lives as we can, but they do choose in their own way.”[5] Which is exactly what Pooka does when we first meet him, forcibly pulling at Anya, barking at her to an unavoidable degree, he directly impacts her actions and decisions, whilst uttering no intelligible speech.

Figure 21. Anya contemplating which direction to go.

Figure 22. Pooka guiding her.

Figure 23.

Figure 24.

Figure 25.

Figure 26.

This common trope of animals acting as a guiding force is also illustrated in the magical and colourful Alice in Wonderland. Alice constantly seeks guidance from the popular Chesire Cat. Similar to Anya’s growing reliance on Pooka, Alice finds the Chesire Cat when she is lost and confused. She asks for directions and answers, and like Pooka, the Chesire Cat provides them in an unusual and odd manner. The similarities of these scenes are striking; the Chesire Cat points Alice to towards the mad tea party which eventually leads to her destination,[6] whilst Pooka guides Anya towards St.Petersburg where she eventually meets Dmitri and Vladimir. Both characters met these animals in an unplanned and bizarre fashion, yet both almost immediately trust them. This dreamy depiction of sudden trust being only presented within human-animal relations makes sense in the animated format of both films. Children’s’ films do not seek to dissect complex issues regarding human animal relationships, nor unrealistic animal representations. The intended viewers will happily go along with the irrational narratives presented to them. As that is the point of these animations, and of Anastasia.

Figure 22.

Figure 23.

Figure 24.

Figure 25.

Figure 26.

Figure 27.

Following the above scene, as Anya and Pooka journey on together towards St. Petersburg, they are met with fellow humans and woodland creatures who emphasise the heart-warming aspect of this film. This sequence of scenes resembles a Disney princess film, with squirrels and birds playing with Pooka as the heroine sings her heart out.

Figure 28. Pooka playing with woodland creatures.

Figure 29.

Figure 30.

Figure 31.

Figure 32.

Figure 33.

Figure 34.

Figure 35.

Figure 36.

Figure 37.

Nearing the dramatic end of the first part of Anya’s journey, the extra-diegetic music crescendo builds up, matching Anya’s diegetic singing, as the camera zooms out and pans up to the golden sketched city skyline, framing Anya and Pooka at a wide angle. This image illustrates the beginning of a whole new adventure that Anya and Pooka are about to embark on. The storybook sketching of the cityscape gives us a glimpse of the magical city scenery to come. The soft white snow surrounding her provides a magical, bright, expansive blank slate for Anya’s awaiting journey. Pooka matches her lively and inspiring energy by running around her and wagging his tail.

Figure 38.

Figure 39.

Figure 40.

Figure 41.

Figure 42.

Emotional value is the focal point for animated children’s films, therefore a visually pleasing narrative of someone who is lost, being guided, and provided comfort to by a friendly, furry creature touch on all the fuzzy spots in the audience’s hearts. Anya and Pooka’s bond is an integral aspect of this film from the start, as he is the first living, breathing being she meets once out of the orphanage and completely on her own. The choice to unite Anya and Pooka before she meets her love interest, and her family proves to be an important one. Pooka is her first and true friend in the foreign world she is thrust into. The audience immediately bonds with Pooka through Anya’s perspective; all the little instances we see of them playing together, Anya singing to him, calling for him, solidify this meaningful bond they share.

Further analysing Anya and Pooka’s relationship, there is an emphasis on totemism, in terms of emotional bonding instead of appearances. Disney, Pixar and Fox’s animations typically portray humans and animal duos in similar lenses. This becomes increasingly more apparent with Anya and Pooka growing closer together as they spend each moment in each other’s company. This is also shown in Ratatouille’s domesticated living situation with Remy and Linguini napping together,[7] mirroring each other. Anastasia doubles the protagonist duo in an opposite aesthetic with Rasputin and Bartok, who share the labels of evil antagonists, (Rasputin far more so than Bartok). Contrasting the warm and friendly aesthetics that illustrate Anya and Pooka, Rasputin and Bartok are specifically depicted amongst charcoal blacks and toxic greens. These visual similarities easily group and identify the forces of good and evil in animated films, allowing an ease of viewing and understanding for children.

Figure 45. Drawing of Anastasia and Pooka.

Figure 46.

Figure 47.

Figure 48.

Figure 49.

Figure 50.

This film, as mentioned before, offers two opposing aesthetic narratives centring on human and animal sidekicks. There are two conflicting storylines, both with their own distinct and defining traits: melodic and sinister music, light and sparkly, versus dark and moody lighting, warm and cold colour palettes, and a heart-warming puppy pet contradicting a witty, “evil” bat sidekick.

Figure 51.

Figure 52.

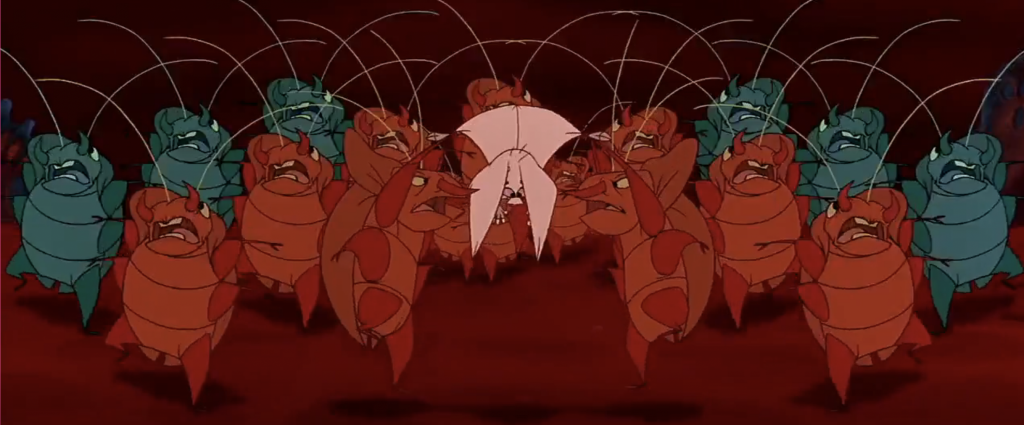

Contrasting Anya and Pooka’s comforting bond, we are presented with rotten Rasputin in his garbs of death, and glowing Bartok. The mise-en-scene rids of all the warm, twinkling lights and friendly faces and is replaced with creepy crawlies, skulls and toxic green liquids when Bartok and Rasputin first appear together. The colour palette that decorates the frames from the start changes into one fitting the corrupt essence of Rasputin. He dwells amongst creatures of the dark who serve his every need, the animals in the antagonist’s scenes vocalise immediately.

Bartok depicts far more anthropomorphic characteristics than Pooka does. ‘The Madagascar Problem’ can be used to analyse these different presentations. As Wells states, that if “you want a speaking animal protagonist, you need to blur the human-animal opposition.”[8] The animators do this in a visually complimentary way with Rasputin and Bartok, as they converse like two human characters would. Wells refers to the term natural-cultural, “the creative and intellectual environment in which the representations of animated animals exist, which raises fundamental questions about the relationship between nature and culture.”[9] This environment is what Rasputin and Bartok appear in, only in animation can images like these exist. However, due to the intended audience being children, these fundamental questions about nature and culture are not necessarily raised. Coinciding with Fox’s children focussed animation, this is not made into a huge deal to dissect.

Even with Rasputin, animals accessorise and emphasise his journey and narrative. Instead of furry woodland creatures, Rasputin sports crickets, creepy-crawlies and odd insects to sing and plot with him. The overall atmosphere is evidently different as the viewers are being told about the dangers Anya and her friends now face. Bartok is seen trying to calm Rasputin down by suggesting less violent methods.

These two battling storylines finally coincide when Pooka spots Rasputin’s toxic green glowing bat like creatures and starts frantically barking as a warning sign. Dogs are typically trusted to guard against thieves and robbers in homes, as well as animals in general being able to spot signs of danger, supernatural or reality based. To reinforce these culturally assumed beliefs is fitting to this genre.

A discussion can be raised regarding the difference between the depictions of evil and good humans and their treatment of animals. Similar to how Pooka provides comfort for Anya, Bartok attempts to raise his master’s spirits after Rasputin exclaims that he is a wreck. Bartok remarks, “actually considering how long you have been dead you look pretty good.”[10] The animal figure is painted in a more likeable light than his human counterpart. This speaks for children’s initial views and romanticisation of furry companions. Bartok is effortlessly funny and charming, lessening the intensity of Rasputin’s cruelness. This balance is essential to keep the light-heartedness of this children’s film intact. However, Rasputin’s heart is shown to be rotten to the core. Unlike Anya’s loving words to Pooka, such as, “sweet dreams Pooka”[11], Rasputin vents his anger on Bartok, “you miserable rodent!”[12] Bartok though, being used to Rasputin’s ways, is always ready to quip back, “oh sure, blame the bat, what the heck, we’re easy targets.”[13]

Figure 68.

Figure 69.

These differing images add nuance to the representation of animated animals in Anastasia, as well as providing interesting vehicles to narrate this layered tale of mysteries, secrets and family. Pooka and Bartok, although only one able to talk, serve their human companions well.

Fox’s Anastasia illustrates a magical and satisfying story of companionship, love, and reunions. The animals along the way, mainly Pooka, star in this animated tale. Our hearts are full by the end of Anya and Pooka’s unpredictable journey, ending in dreamy Paris. Even Bartok gets hit with Paris’s cupid, placing animals in a better light than most humans in this fictional universe. The audience will fondly remember Anya’s scruffy puppy and Rasputin’s charming bat.

References:

1 – Anete Kuhn, Guy Westwell, A Dictionary of Film Studies (2.ed.), (Oxford University Press: 2020)

2 – Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture. (Rutgers University Press: 2009)

3- Ibid.

4- Bluth, Don, & Goldman, Gary, Anastasia, (20th Century Fox, 1997)

5- Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, a

6- Geronimi, Clyde, & Jackson, Wilfred, & Luske, Hamilton, Alice in Wonderland, (Walt Disney, 1951

7- Lewis, Brad, Ratatouille, (Walt Disney: 2007).

8- Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture. (Rutgers University Press: 2009)

9- Ibid.

10- Bluth, Don, & Goldman, Gary, Anastasia, (20th Century Fox, 1997)

11- Ibid.

12- Ibid.

13- Ibid.

Bibliography:

- Anete Kuhn, Guy Westwell, A Dictionary of Film Studies (2.ed.), (Oxford University Press: 2020) https://idp.shef.ac.uk/idp/profile/SAML2/POST/SSO;jsessionid=0FF7CB7321577791AB761B14A5592138?execution=e1s1&_eventId_proceed=1 <accessed on 18th January>

- Weekes, Princess, Anastasia Is Now a Disney Princess: How This Little Movie Ruined Russian History For 1000 Years, (themarysue: 2020). https://www.themarysue.com/anastasia-disney-princess-russian-history-fail/ <accessed on 19th January>

- Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture. (Rutgers University Press: 2009) https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1746847710386442 <accessed on 16th January>

Filmography:

- Bluth, Don, & Goldman, Gary, Anastasia, (20th Century Fox, 1997)

- Geronimi, Clyde, & Jackson, Wilfred, & Luske, Hamilton, Alice in Wonderland, (Walt Disney, 1951)

- Lewis, Brad, Ratatouille, (Walt Disney: 2007)

Further reading: