Fig.1 An American Tail poster by Drew Struzan. It comprises the American Dream spirit and the hopes of the immigrants

An American Tail tracks the adventures of Fievel Mousekewitz a brave (and reckless) little mouse, his Russian-Jewish family, and their treacherous journey from Russia to New York in the search for the American Dream that will put some distance between them and cats… or so they thought. The film tells a story within a story, the separation and reunion of Fievel with his family, and at the same time the real historical context framing it. All in all, An American Tail is a very human story narrated by animals for children –and not so children-, in which mice join forces to fight back oppression and recover their freedom in late 19th century America.

Professionally departing from Disney but still preserving its classic style and influence[1], Don Bluth makes use once again of rodents to present an emotional story in his typical fashion: dealing with complex and dark topics that may seem unsuitable for a young audience (such as racism, religious intolerance, poverty or exile) but balancing it with songs, lovable characters, an adorable design, and detailed and carefully hand-drawn 2D animation. Resorting to animals -and especially smaller ones-, offers filmmakers the opportunity to explore the world from different perspectives, which works extremely well in animation and children-focused films. In An American Tail comparison generates pleasure through recognition, fulfilled curiosity, and surprise. We, humans, become the Others, and that results interesting and visually amusing. The film provides a representation of animals that leaves some inconsistencies[2] unapologetically unresolved. Some of them are significantly anthropomorphised, some are also animalised, and some are none of the two. Mice and rats mainly comply with (and “personify”) the existing cultural stereotypes about both, humans and animals, while humans are relegated to a background position.

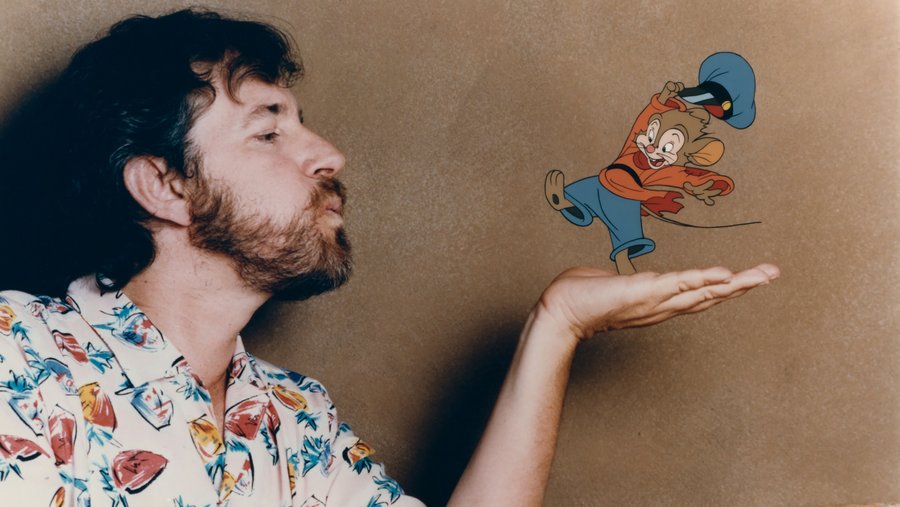

Fig. 2 Devoted fan of this format -and Jewish himself; Steven Spielberg worked as the executive producer, and against Bluth’s initial wishes, chose Fievel’s name after his grandfather. [3b]

Fig.3 The mice represent the Great Wave of European immigrants that moved to the US between 1880 and 1930

In a general view, immigration is the central theme of the film, and sets the tension between the concepts individuality and collectivity. The mice that An American Tail introduces are unique individuals from different social classes and backgrounds – just like humans! – but with two important things in common: the shared status of immigrants, and a past or present traumatic experience involving cats. All of it holds a connection with the deeply rooted American ideas around identity and sense of belonging. The circumstances are relatable to the mice no matter their origin because cats seem to embody the enemy everywhere in many different forms [fig.5]

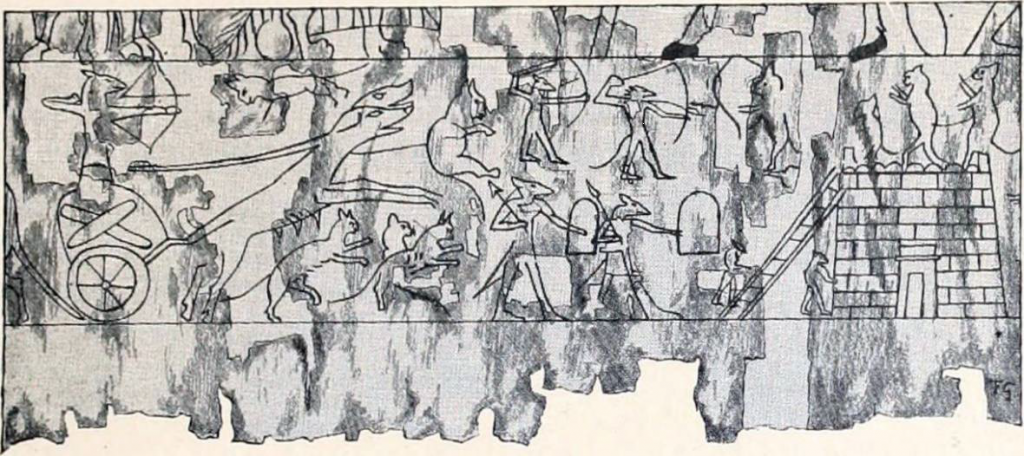

Fig.4 Cats and mice have been stereotypically considered to be adversaries for thousands of years. Here, a reconstruction of the War of Mice and Cats of Turin papyrus. Some papyri depicted animals inverting the natural roles of their own species, and performing human activities.

Fig.5 The Italian cats represents the mafia and political corruption.

Fig.6

A common goal against the cats unites and equalises the mice, encouraging them to work together regardless of hierarchies or roots. But for them to become one (quite literally if we think about the Giant Mouse of Minsk[3]) someone needs to light the fuse. It is mice like Fievel, Bridget or Gussie [fig. 7, 8, 9] who, in showing their individuality, motivate the change and reinforce the sense of community. Fievel is an example of the nice mouse trope, represents the future of the next generation of immigrants and stands out thanks to his innocence and bravery, Bridget is an Irish-born nod to the American suffragette, trying to denounce injustice and to fight for mice rights after her parents’ murder, and Gussie Mausheimer [fig.8] is a wealthy German representing the upper class, who organises the rally against the cats. It is surely not by chance that these characters represent women and children – a part of the oppressed population.

Fig.7 With oversized ears and clothes, Fievel’s design plays the adorability card very well.

Fig.8

Fig. 9 Bridget’s colours are green, white, and orange. What a coincidence!

Fig.10 Real American suffragettes. FPG/Archive Photos/Getty Images

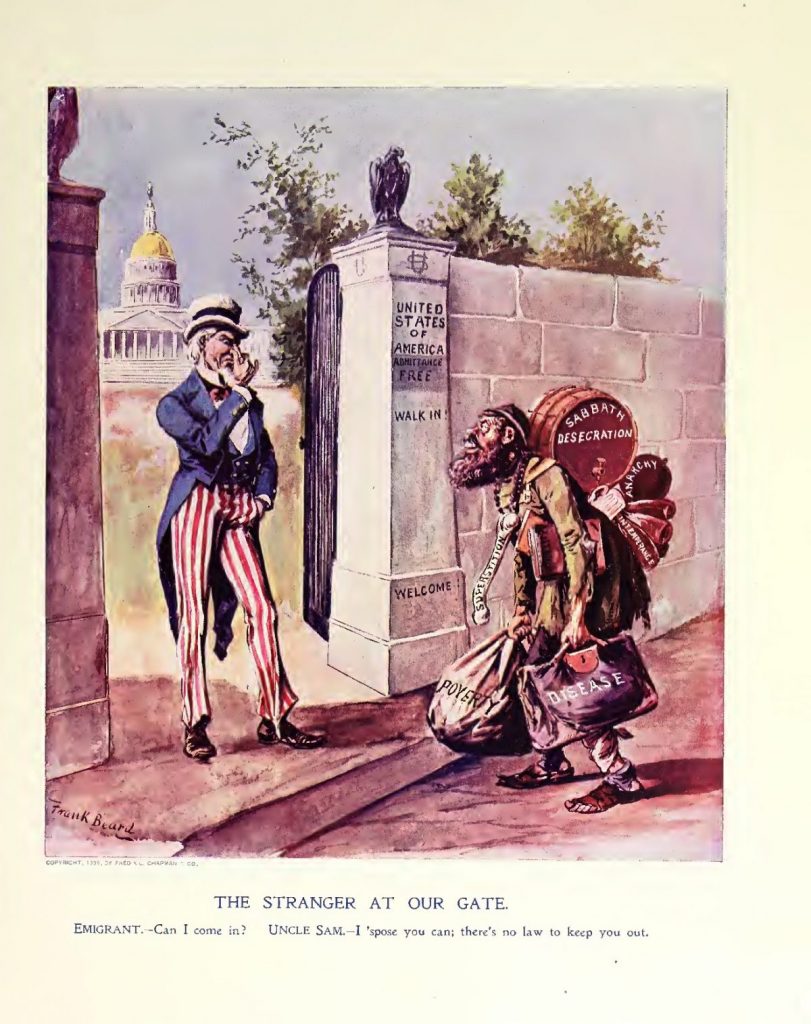

Fig. 11 Political cartoon illustrating Uncle Sam’s rejection to the arrival of a Jewish immigrant. 1896 edition of the Ram’s Horn

On one side of the coin, just like Fievel, mice have occupied roles in folklore, fables and tales where the small and apparently vulnerable rodent has to face a much bigger threat or challenge that seems like an impossible feat. These stories attribute mice virtues like courage, ingenuity, resourcefulness. On the other side of the coin, its real life reputation does not leave it in a very favourable position. According to the Bible, mice are “unclean”, medieval bestiaries describe them as light-fingered and greedy, and they are overall considered a symbol of destruction and pestilence.[4] Let’s not forget that cats were, after all, originally domesticated with the intention of keeping rodents away from the houses.

The Mousekewitz soon found out that things were not as easy as they thought they would be. At the docks, like many real immigrants at the time, the family is forced to change their names [fig.12,13]. While being true that the film does not deal with it in depth once the family arrive in New York, their religion and identity are an important element of the story (we can see it at the beginning, when the conflict between cats and mice in Russia is depicted as an anti-Semitic event[5]).

Fig.12

Fig.13

Fig.14 Immigrant Inspection at Ellis Island, 16 July 1910. National Park Service

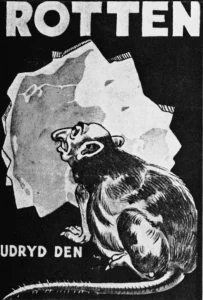

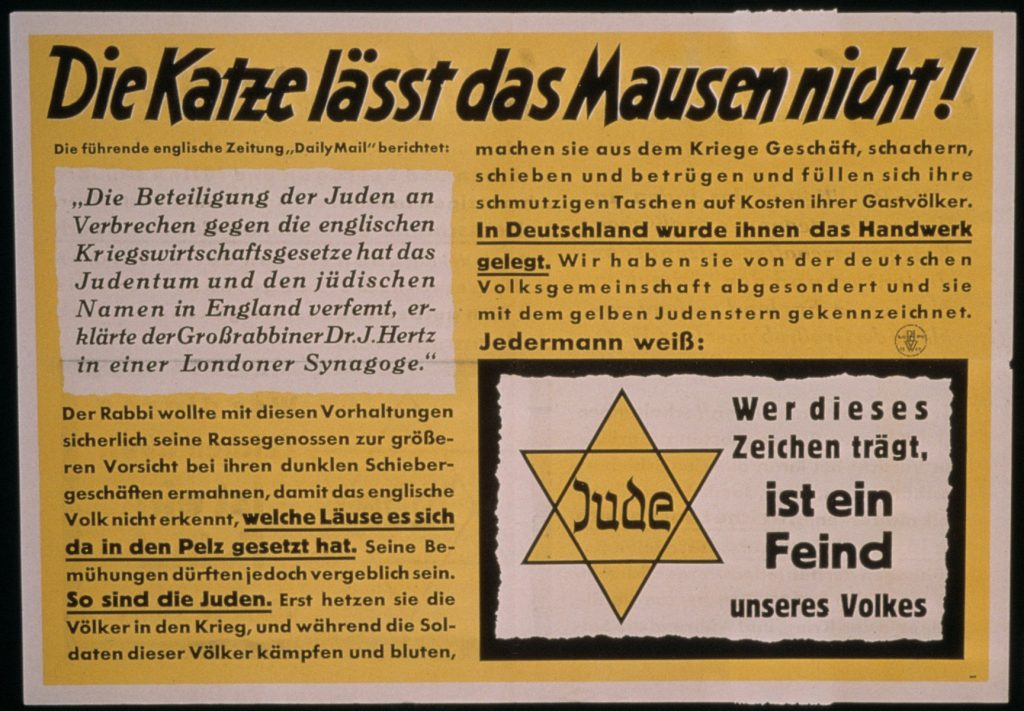

Close to this topic lies the comparison drawn between mice or rats and Jewish people. It became recurrent during the first half of the 20th century and involved applying to the Jewish population the negative set of features assigned to mice, in order to dehumanise – and animalise – them. The allegory was exploited by the Nazi propaganda, which defined Jewish as undesirable, greedy and an invasive threat; a subhuman problematic collective they needed to get rid of. Or in short, as vermin.

Fig. 15 “The cats will not let the mice be!” Nazi Propaganda, 1942. US Holocaust Memorial Museum

‘Vermin’ is a socially constructed term (…) applied to any animal humans have no use for, or worse yet, against whom humans must compete for resources. Labeling animals as vermin is the first step in justifying their eradication.”

Richard De Angelis [6]

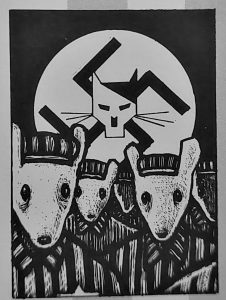

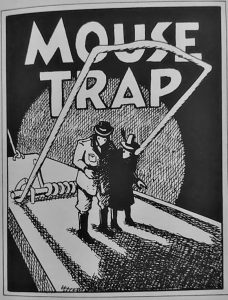

In this sense, the film connects with the simultaneous[7] graphic novel MAUS, also representing mice as the oppressed and cats as the oppressor. Spiegelman decided to illustrate the story using animals because it “allows you to defamiliarize the events, (…) they are coming at you in a language you are not used to hearing” [8]

Fig.17 Mice dressed as camp prisoners, with the cat version of Adolf Hitler and the swastik

Fig.18 Cats as Nazi soldiers corner Vadek, the Jewish main character

Fig.19 Allegory of the Nazi threat looming over the Jewish characters

Fig.21 Working Italian boy NYC, c.1910. Lewis Hine. Eastman House

However, while MAUS re-appropriates, adopts and subverts this prejudiced image, An American Tail chooses to maintain some of the common tropes and stereotypes, like the dichotomy mouse – good / rat – bad. Rats tend to be villainized and given a different animal status, especially when mice appear in the same story. In the case of An American Tail, Warren T. Rat [fig.22] and Moe are the only “rodents” that could be considered mean. Warren T. Rat’s business consists on racketeering and scamming mice into paying him for protection against the Mott Street Maulers. Eventually, the film reveals that is actually a cat in disguise and leader of the gang (he wears a long coat to hide his features and a snout mask). His decision to pass himself off as a rat is an intention to deceive and take advantage of the mice, who will trust him thanks to the fake rodent appearance. He promises Fievel help before selling him to an abusive rat called Moe. Moe is a rat that runs a sweatshop [fig.20] in which workers are exploited, including children.

Fig.20 On several occasions humans appear onscreen, unaware of what is happening at their feet. (On the right an immigrant woman uses a sewing machine)

Both characters share a similar dark brown skin tone, sharp-teethed malicious smirks, and appear smoking cigars [fig. 22, 23]. This habit relates with an old idea of hypermasculinity giving the character an aggressive or more authoritarian look, especially in combination with Moe’s brutish appearance and exaggerated salivation. The cigar also alludes to certain levels of wealth or power, which matches these two characters who thrive at the expense of others. In the case of the presumptuous Warren T. Rat, his greed and love for money are enhanced by his top hat and golden teeth. Based on this, the film is somehow suggesting that only mice and not rats are in danger, eliminating the possibility for an alliance between the two. But since there is only one real rat, this will remain a mystery.

Fig.22

Fig.23

Warren T. Rat’s character is the biggest inconsistency that gets blatantly ignored in the film. His size varies throughout the scenes, defying the inner logic in order to suit the plot. He can be seen inside an old threadbare suitcase where he is no bigger than a small rat if we compare him to the rest of the objects around him, or significantly smaller than Moe (the real rat) when he sells Fievel [fig. 23]. Contrarily, in scenes including other cats he appears as a regular size Havana Brown cat [fig. 25].

Fig.24

Fig.25

At the end of the day, An American Tail is an animation film with children as its primary target audience. Animals are here, as Wells stated, a “convenient vehicle by which the imperative for a coherent narrative and thematic vision may be compromised”[9]. It is understandable then, that the film’s strongest attractive points have to do with its visual aesthetics and a simplified plot; and that, following the same reasoning, the presence of animals serve as entertainment and “pleasurable education”[10]. In An American Tail, the (very) anthropomorphised animals can do many things, but are, at same time, limited by their own nature. This anthromorphism is used as a means to illustrate and fictionalize historical real-world narratives under the pretext of ancestral predator and prey relationships. There is a constant back and forth between the main animal story and the human historical context to remind the audience that this is not an animal-only populated world, but a relegated layer of the one we live in. Animals and humans share the same space and undergo the same equivalent calamities, and yet in a modernised urban world humans and animals seem completely disconnected to the point that this co-existence goes unnoticed. By means of characterisation based on widespread conventions, mice and rats represent -without challenging them-, different stereotypes that reinforce the dichotomy between mice and rats and how they are perceived. Despite being an 80’s film set in the late 19th century, the theme and sentiment resonate with many still today.

[1] Bluth wanted to emulate a style similar to Disney animation from the 1940s – From “An American Tail” Wikipedia

[2] Some of these inconsistencies are mentioned in this Zoom entry.

[3b] Don Bluth thought ‘Fievel’ was a name too complicated to remember for non-Yiddish audiences. – From “An American Tail” Wikipedia

[3] A mechanic, huge and scary mouse that they build to terrify the Mott Street Maulers gang at the end of the film

[4]Warren R .,Dawson. ‘The Mouse in Fable and Folklore’, Folklore, 36:3, (1925) 238-243

[5] See the previously linked Zoom about An American Tail for a more specific article to the opening scene.

[6] Richard De Angelis. “Of Mice and Vermin: Animals as Absent Referent in Art Spiegelman’s Maus.” International Journal of Comic Art 7.1 (2005): 230–249 (p.231)

[7] So simultaneous that Spiegelman considered suing, and rushed the publication of the book to anticipate to the release of the film. More in https://www.slashfilm.com/760513/why-steven-spielbergs-an-american-tail-was-accused-of-plagiarism/

[8] Cited in Linda Hutcheon, “Literature meets history: Counter-discursive ‘comix.’”, Anglia: Zeitschrift fur Englische Philologie 117(1), (1999) 4-14 (p.7)

[9] Paul Wells, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture, Rutgers University Press, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central, (p.22) <http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=413877>

[10] Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film, Reaktion Books, Limited, 2004. ProQuest Ebook Central, (p22) <http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=449396>

Bibliography:

Attanasio, Paul, ‘An American Tail’, Washington Post, (22November 22 1986) <https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/anamericantailgattanasio_a0ad78.htm> [accessed 3 November 2022]

Bluth, Don, dir., An American Tail (Universal Pictures, 1986)

Boivin, Genia. 2019. ‘America Does Not Want Bad Kitties. The Representation of Cats in “An American Tail”’, animationstudies 2.0 <https://blog.animationstudies.org/?p=3341> [accessed 10 November 2022]

Burack, Emily, ‘Was Mickey Mouse an Anti-Semitic Caricature of Jews?’, hey alma, (28 March 2019) <https://www.heyalma.com/was-mickey-mouse-an-anti-semitic-caricature-of-jews/> [accessed 3 November 2022]

Burt, Jonathan. Animals in Film, Reaktion Books, Limited, (ProQuest Ebook Central, 2004), p.22

Cawley, John (1991). “An American Tail”. The Animated Films of Don Bluth. Image Pub of New York. pp. 85–102

Dawson, Warren R. ‘The Mouse in Fable and Folklore’, Folklore, 36:3, (1925) 227-248, <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/0015587X.1925.9718327>

De Angelis, Richard. “Of Mice and Vermin: Animals as Absent Referent in Art Spiegelman’s Maus.” International Journal of Comic Art 7.1 (2005), 230–249.

Hollebe, Julia, The Depiction of Jews as Mice in the Graphic Novel “Maus” by Art Spiegelman, (2018), Múnich, GRIN Verlag, https://www.grin.com/document/889176

Hutcheon, Linda. “Literature meets history: Counter-discursive ‘comix.’” Anglia: Zeitschrift fur Englische Philologie 117(1), (1999) 4-14 < https://doi.org/10.1515/angl.1999.117.1.4>

IMDb, IMDb, 1990 <https:// www.imdb.com/> [accessed 2 November 2022]

Jennings, Collier. 2022. ‘Why Steven Spielberg’s An American Tail Was Accused Of Plagiarism’, /Film <https://www.slashfilm.com/760513/why-steven-spielbergs-an-american-tail-was-accused-of-plagiarism/> [accessed 10 November 2022]

Ness, Mary, ‘This, Too Started With a Mouse: The Great Mouse Detective, Tor.com (2015) <https://www.tor.com/2015/10/22/this-too-started-with-a-mouse-disneys-the-great-mouse-detective> [accessed 6 November 2022]

pbiasizzo, An American Tail trailer, online video recording, YouTube, 4 Julio 2009, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kvZfEQ_pMdg > [accessed 13 November 2022]

Rawlings, Amber, ‘Why Is Hollywood So Obsessed With Talking Rats?’, VICE, (7 June 2021) <https://www.vice.com/en/article/5db3vx/why-is-hollywood-so-obsessed-with-talking-rats> [accessed 3 November 2022]

Richmond, Chris, Schoentrup, Drew, TvTropes, 2004 <https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/NiceMice> [accessed 13 December 2022]

Richmond, Chris, Schoentrup, Drew, TvTropes, 2004 <https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/YouDirtyRat> [accessed 13 December 2022]Richmond, Chris, Schoentrup, Drew, TvTropes, 2004 < https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/ResourcefulRodent> [accessed 13 December 2022]

Smithsonian, ‘History of Sweatshops: 1880-1940’, National Museum of American History Behring Center, [n.d] <https://americanhistory.si.edu/sweatshops/history-1880-1940>

Spiegelman, Art, Chute, Hillary, ‘Why Mice?’, New York Review, (20 October 2011) <https://www.nybooks.com/online/2011/10/20/why-mice/?lp_txn_id=141588> [accessed 17 December 2022]

Spiegelman, Art, The Complete MAUS (Harlow, England: Penguin Books, 2003)

Trumbore, Dave, “‘An American Tale’: Modern Lessons on Racism, Immigration, and Human Decency,” in The Collider, November 21, 2016. <https://collider.com/an-american-tail-30th-anniversary-themes-racism-immigration/#immigrants-refugees> [accessed 23 December 2022]

US History, ‘The Rush of Immigrants’, U.S. History Online Textbook,<https://www.ushistory.org/us/38c.asp> [accessed 4 January 2023]

Wells, Paul. The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture, Rutgers University Press, (ProQuest Ebook Central, 2008), p.22-23

Wikipedia. 2001. ‘An American Tail’, Wikimedia Foundation, Created 10 September 2004, Last modified 14 January 2023, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/An_American_Tail> [accessed 2 November 2022]

Further reading:

Boivin, Genia. 2019. ‘America Does Not Want Bad Kitties. The Representation of Cats in “An American Tail”’, animationstudies 2.0 <https://blog.animationstudies.org/?p=3341>

Cawley, John (1991). “An American Tail”. The Animated Films of Don Bluth. Image Pub of New York. pp. 85–102

Richmond, Chris, Schoentrup, Drew, TvTropes, 2004 https://tvtropes.org

Spiegelman, Art, Chute, Hillary, ‘Why Mice?’, New York Review, (20 October 2011) <https://www.nybooks.com/online/2011/10/20/why-mice/?lp_txn_id=141588>

Spiegelman, Art, The Complete MAUS (Harlow, England: Penguin Books, 2003)

Trumbore, Dave, “‘An American Tale’: Modern Lessons on Racism, Immigration, and Human Decency,” in The Collider, November 21, 2016. <https://collider.com/an-american-tail-30th-anniversary-themes-racism-immigration/#immigrants-refugees>

Further viewings

Draper, Matt, The Disney/Don Bluth Animation War – The Story of A Rise, Fall & Renaissance, YouTube, 1 June 2022, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WKCLqeh0fjw> [accessed 12 January 2023]