“We can no longer live as rats. We know too much.”

The Secret of NIMH is remembered by many as a dark, creepy, and disturbing film, with retrospectives published in recent years referring to it as leaving basically every kid who sees it with a lingering dread. Don Bluth’s directorial debut after leaving the Walt Disney Animation company tells the story of Mrs Brisby (re-named so as to avoid a legal battle with the producers of the popular Frisbee™): a field mouse who must move her home and children before the harvest season begins and they are destroyed by the farmer’s plough. To complicate matters, her son Timothy is deathly sick with pneumonia and cannot leave his bed, Mrs Brisby’s husband Jonathan has recently died in mysterious circumstances, and the farm cat Dragon is on the prowl. Oh, and there are a group of super-intelligent ex-lab rats living in the rosebushes nearby who possess both electricity and a magical glowing amulet. Confused? You probably should be.

The film is loosely based on the popular 1971 children’s book Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH by Robert C. O’Brien but adds fantastical elements in order to showcase the ‘old-school’ animation style favoured by Bluth and his fellow Disney-abdicators. Reviewers praised it as “something of a technical and stylistic triumph” but were unconvinced by the unnecessarily complicated plot, with many citing the deus ex machina of the magical amulet as a major point of confusion.[1] Bluth would later state that the animators “didn’t really think it was necessary to explain it further”.[2] Arguably, they could have spent more time exploring the hyper-intelligence of the rat colony, whose DNA has been altered by mind-bending injections given to them as part of scientific research being conducted by the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH), giving them self-consciousness and the ability to read and write as well as the capacity to steal electricity from the farmhouse. The interspecies conflict between the non-human animals and humans is one of the most compelling aspects of the film, raising important ethical questions about our relationship with species considered to be ‘lesser’ than ourselves.

The drama of NIMH largely takes place in what we might assume to be a fairly mundane setting, a rural farmhouse and the surrounding land. We quickly learn that the annual harvest, which humans rely on in order to keep supermarket shelves stocked, is perceived by the farm’s wild inhabitants as a genocidal act of God which they must flee or else risk their lives. This imagery is instantly reminiscent of Nazi propaganda which sought to compare the ethnic Jewish peoples to vermin in order to breed distrust and disdain in the German population.[3]

Anti-Semitic cartoon from Austrian Newspaper ‘Das Kleine Blatt’, depicting Jewish people as rats. Captioned: “Deutschland den Deutschen!” (Germany for the Germans!)[4]

Immediately viewers are sympathetically aligned with the non-human animals of the film, who although anthropomorphised, are still representative of a very real problem in the age of industrial agriculture. The ploughing of fields, as well as other intensive farming practices such as spraying potentially lethal pesticides, risks disrupting delicate eco-systems and maiming or displacing the native wildlife. This point is emphasised during a frantic confrontation between the mice and the industrial machinery of the farmer’s plough, which unfeelingly tears through the landscape and threatens to destroy anything in its path. Nothing, it seems, can repress the unstoppable force of industrialisation.

Through the demure and diminutive figure of Mrs Brisby, we are introduced to various other species who inhabit the fields: shrews, crows, and a disturbingly old owl with glowing yellow eyes. These creatures all appear to live in a fairly harmonious society with one another; a crow called Jeremy who serves as the movie’s main source of comedic relief shows no hint of his species’ propensity to eat baby mice, instead acting as a close friend and guardian of Mrs Brisby and her family. Whilst Mrs Brisby is nervous when she is advised to visit the Great Owl (touted as ‘the wisest creature in the forest’) because she is cognizant that owls eat mice, she comes away from the encounter unscathed. Instead, the Great Owl informs her that he knew of her late husband, and instructs her to seek out the local rat colony in order to safely move her home before the ploughing begins. Thus, the non-human animals of the film are united in their fight to survive, offering communal mutual aid in order to avoid extinction by their human oppressors. By introducing us to creatures which are usually considered vermin on a personable, human level, NIMH encourages its audience to empathise with the species who are routinely labelled as ‘expendable’ in the name of seemingly unlimited human expansion. As Maud Ellmann argues in her work on the depiction of rats in literature, “individuality humanises: to kill rats is to exterminate a health hazard; to kill a single rat is more like murder.”[5]

In NIMH, this ecological narrative runs alongside one straight out of science-fiction – the escape of a colony of ex-laboratory rats who have been inadvertently injected with intelligence-enhancing drugs. In a fantastical flashback scene involving a mystical spinning orb, the leader of the colony Nicodemus recounts the circumstances which lead to the rats’ escape from NIMH. For a film which is aimed towards children, these scenes are especially dark – close-up shots of animals with humanised facial expressions languishing in barren laboratory cages, crying out or clutching one another in fear. Bluth pointedly shows images of animals which are more often emotionally aligned with humans before introducing the rats, by including fairly long shots of Beagles (the breed of dog often favoured by research scientists) [figure 1] and a primate mother with her young offspring [figure 2].

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

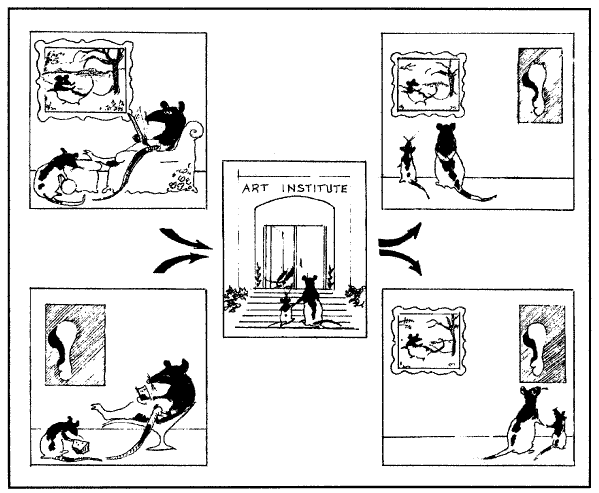

The visual narrative of the scene guides the viewer to accept the rodent-inhabitants of the laboratory as victims by first tugging on their emotional heartstrings with ‘man’s best friend’ and man’s closest non-human relative. This reinforces “what Derrida describes as an ‘artificial, infernal, virtually interminable survival’, whereby animals are brought to life in order to be killed, enslaved, subjected to experiments, or genetically reorganised in the laboratory”, prompting a reflection on the ways in which humanity produces and utilises non-human animals as an expendable resource rather than beings whose lives are of equal value to our own.[6] This is a theme explored by the science-fiction writer and former research psychologist Alice Sheldon (under the penname James Tiptree Jr.), whose short story The Psychologist Who Wouldn’t Do Awful Things to Rats (1976) explores the emotional connection between research scientists and their subjects.[7] The protagonist watches as his colleagues “do a variety of awful things to their rats and other animals: starve them, slice them, blind them, drive electrodes into their skulls, “sacrifice” them, chop off their heads”, and develops deep empathy for their plight. Sheldon herself produced anthropomorphic caricatures of the rats that she studied as part of her doctorate in psychology, depicting what she imagined would happen if they were to visit a museum rather than being subjected to the object-preference experiments of the laboratory.

“Given each rat family’s familiarity with a certain style of art at home, which sort of painting would they choose to look at if they visited a museum?”[8]

It therefore seems fitting that it is the actual experimentation on the rodents which is conveyed as the most abjectly horrific aspect of the scientific research, as the animals are pinned down and injected with mind-altering chemicals [figure 3]. The film represents this in a weird and wonderful sequence of abstract imagery, reminiscent of sequences from Disney’s experimental animated picture Fantasia (1940) [figure 4]. The rats physically mutate and transform, growing larger and more muscular with imagery that recalls the horror genre, before it is revealed that they have gained the ability to read and comprehend English. One of the key questions posed by the film here is whether the laboratory rodents become more worthy of existence as a result of their increased intelligence. One of the main arguments for human species superiority is that our capability for abstract and complex thought grants us dominion over ‘lesser’ species, but this is complicated by the possibility of animals attaining an equal level of comprehension and communication.

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

However, this is only the beginning of the rat’s journey with their newfound intelligence. They go on to establish an urbanised society beneath the farmhouse, stealing electricity from the farmer and constructing their own mechanical apparatus such as elevators. This ultimately results in conflict between the rats themselves, as some of them are determined to continue their current way of life whilst others believe it to be ethically wrong to siphon the farm’s electricity supply. In this sense, the rat society is shown to be much like human society – with different factions arguing either for or against the subjugation of others for their own material gain. As Ellmann concludes, “the rat is the phobic image of our own excess, our destruction of the balance of nature, our refusal to let ethical or ecological considerations interfere with our rampageous consumption of the planet.”[9] Rats and humans have co-existed for centuries, with both species’ ability to adapt and overcome the key to their ongoing success. Through the story of NIMH we are forced to confront the inherent similarities between ourselves and rodents, and examine the ethical implications of our continued industrialisation on the natural world.

Ultimately, despite its status as nightmare-fuel for young and impressionable children, The Secret of NIMH holds up as a compelling animated argument for the importance of ecologically mindful agricultural practices and the disuse of non-human animals in scientific research laboratories. By encouraging viewers to align themselves with the marginalised wildlife of the natural landscape the film promotes empathy and conscientiousness, encouraging children and adults alike to question the societal categorisation of certain animals as ‘vermin’ as well as the continued utilisation of other species for the advancement of human ideals. With countless laboratory animals having been sacrificed in the name of progress, it is important that we continue to constructively engage with the systems which determine whether one life is inherently more worthy or meaningful than another.

Monument to the Laboratory Mouse, Siberia, Russia.

Irina Gelbukh – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27166481>.

Footnotes

[1] Vincent Canby, “‘N.I.M.H.,’ SHADES OF DISNEY’s GOLDEN ERA”, The New York Times, 1982 <https://www.nytimes.com/1982/07/30/movies/nimh-shades-of-disney-s-golden-era.html> [Accessed 29 May 2020].

[2] Adam McDaniel, “Remembering NIMH: An Interview With Don Bluth”, Adammcdaniel.Com, 2009 <http://www.adammcdaniel.com/DonBluth/Don_Bluth_Interview3.htm> [Accessed 29 May 2020].

[3] Maud Ellmann, “Writing Like A Rat”, Critical Quarterly, 46.4 (2004), 59-76 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0011-1562.2004.00597.x, p. 59.

[4] Das Kleine Blatt, 1939, p. 1 <http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=dkb&datum=19390202&seite=1&zoom=33> [Accessed 30 May 2020].

[5] Ellmann, p. 59.

[6] Maud Ellmann, “Cold Noses At The Pearly Gates”, Textual Practice, 24.4 (2010), 707-724 https://doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2010.499659, p. 711.

[7] Alan C. Elms, “The Psychologist Who Empathized With Rats: James Tiptree, Jr. As Alice B. Sheldon, Phd”, Science Fiction Studies, 31.1 (2004), 81–96 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/4241230> [Accessed 29 May 2020].

[8] Elms, p. 86.

[9] Ellmann, p. 65.

Further Reading

Carpenter, Les, “30th Anniversary Of Secret Of NIMH – Gary Goldman Exclusive!”, Traditional Animation, 2012 <https://www.traditionalanimation.com/2012/30th-anniversary-of-the-secret-of-nimh-gary-goldman-exclusive/> [Accessed 29 May 2020]

Greshko, Michael, “Maybe Rats Aren’t To Blame For The Black Death”, Nationalgeographic.Com, 2018 <https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2018/01/rats-plague-black-death-humans-lice-health-science/> [Accessed 29 May 2020]

McDaniel, Adam, “Remembering NIMH: An Interview With Don Bluth”, Adammcdaniel.Com, 2009 <http://www.adammcdaniel.com/DonBluth/Don_Bluth_Interview3.htm> [Accessed 29 May 2020]

Further Watching

Anthony, Theo, Rat Film (United States: Independent Lens, PBS, 2016)

Bird, Brad, Ratatouille (United States: Walt Disney Pictures, Pixar Animation Studio, 2007)

Bowers, David, and Sam Fell, Flushed Away (United Kingdom, United States: Aardman Animations, Dreamworks Animation, 2006)

National Geographic, Welcome To The Rat Temple, 2012 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2OOs1l8Fajc> [Accessed 29 May 2020]

Spurlock, Morgan, Rats (United States: Dakota Group, Discovery Channel, 2016)

Bibliography

Canby, Vincent, “‘N.I.M.H.,’ SHADES OF DISNEY’s GOLDEN ERA”, The New York Times, 1982 <https://www.nytimes.com/1982/07/30/movies/nimh-shades-of-disney-s-golden-era.html> [Accessed 29 May 2020]

Das Kleine Blatt, 1939, p. 1 <http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=dkb&datum=19390202&seite=1&zoom=33> [Accessed 30 May 2020]

Ellmann, Maud, “Cold Noses At The Pearly Gates”, Textual Practice, 24 (2010), 707-724 <https://doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2010.499659>

Ellmann, Maud, “Writing Like A Rat”, Critical Quarterly, 46 (2004), 59-76 <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0011-1562.2004.00597.x>

Elms, Alan C., “The Psychologist Who Empathized With Rats: James Tiptree, Jr. As Alice B. Sheldon, Phd”, Science Fiction Studies, 31 (2004), 81–96 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/4241230> [Accessed 29 May 2020]

Harmetz, Aljean, “EX-DISNEY ANIMATORS TRY TO OUTDO THEIR MENTOR”, The New York Times, 1982 <https://www.nytimes.com/1982/07/14/movies/ex-disney-animators-try-to-outdo-their-mentor.html> [Accessed 29 May 2020]

McDaniel, Adam, “Remembering NIMH: An Interview With Don Bluth”, Adammcdaniel.Com, 2009 <http://www.adammcdaniel.com/DonBluth/Don_Bluth_Interview3.htm> [Accessed 29 May 2020]

Rovner, S, and Y Rovner, “Rats! The Real Secret Of NIMH”, The Washington Post, 1982 <https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1982/07/21/rats-the-real-secret-of-nimh/9d314dfc-e650-4705-822e-a56b954c8a2d/> [Accessed 29 May 2020]

Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, And Culture (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2008), pp. 26-59