In Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007), Harry contends with his isolation as a result of the ministry of magic, and a large portion of his fellow students, believing him to be lying about his experiences at the end of his last school year. These experiences include the return of the dark wizard, Voldemort, and the death of fellow student, Cedric Diggory. His isolation due to his grief about Cedric’s death finds a reflection in creatures called thestrals, which are isolated in the sense that they are invisible to people who have no experience with death, and therefore removed from the ordinary life of the school. The ministry seeks to interfere at Hogwarts in the form of Professor Umbridge, who presents a front of sweetness by dressing in pink and lining the walls of her office with moving portraits of kittens.

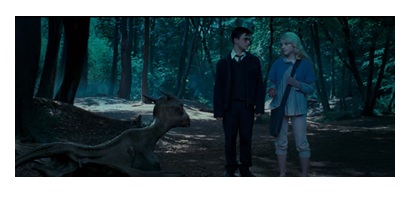

The misunderstood and largely avoided spectres of death, the thestrals, are symbolic of the outsider in Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007). They are most closely associated with the character Luna Lovegood. Luna embodies the idea of faith in the film, to the extent that she believes in all sorts of unproven creatures which infuriates the rational Hermione; but this faith is essential to Harry’s journey towards accepting his difficult circumstances and dealing with death, which he does in part through his interactions with the thestrals and Luna. Luna as a character has a remarkable level of resilience, which is depicted visually, in the scene where Harry finds her with the thestrals in the forbidden forest, by the close-up on her lack of shoes (‘Your feet, aren’t they cold?’ says Harry, ‘A bit,’ replies Luna, perfectly at ease). Her resilience is also indicated by the calm with which she tells Harry about her mother’s death when she was nine, with the two of them walking slowly towards the camera, which is positioned low down and to the right behind a baby thestral. This framing portrays Harry and Luna as equals approaching the issue of death, symbolised by the thestral. But the design of this scene around a baby thestral indicates their discussion really centers on the idea of hope despite death, because the thestral, as a baby, is eagerly and excitedly squawking and stepping towards them in the hope of food. When they stop walking, the camera slowly drifts upwards dreamily, as the thestral tilts its head to the side, curiously regarding the apple Luna has pulled from her bag. The calm, dreamy tone of this scene contributes to the portrayal of the thestrals, and Harry’s experiences of death, as things which do not have to be frightening and isolating. Luna’s resilience and calm demeanor exemplifies how faith and belief, whether in wondrous creatures, or in the goodness of the world when all hope seems lost (as it does to Harry just before this scene), is possible and admirable over Harry’s self-isolating outlook of bleak realism and despair at his reality.

The blue colour palette of this scene where Luna and Harry bond over the thestrals, with Luna’s outfit, eye colour, and the blue mist between the trees, contributes to its calm, ethereal, other worldly quality, which emphasizes the thestrals as something outside the regular pressures of Harry’s everyday life and experience. The fantasy genre’s emphasis on things which are outside the realms of normality makes it particularly appropriate to deal with the theme of death. The blue in this scene is the colour of Ravenclaw, the house to which Luna belongs, which emphasises knowledge and cleverness as the most important traits for its members. At first this seems odd since Luna does not seem at first glance to be an overly rational character. However, she does need a certain level of rational detachment in order to see things from her own unique perspective without being influenced by others calling her crazy. It is this outside perspective, this ability to see things from outside of his own emotions which helps Harry; despite Luna’s seeming lunacy, this clear headedness and knowledge of what really matters is what places her in Ravenclaw, and also places her in this scene in which Harry is seeking a way to remain strong in spite of his troubles.

As creatures of fantasy which are animated, the thestrals physical appearance is designed as disturbingly skeletal to imply death, which is underscored through their reptilian spiky features and furlessness, as reptilian characteristics are seen as being strange because of humanity’s perspective as mammals. This shifts them further into the realm of the other, that less easily understood side of life which death comes under. They are shown to be contradictory, at once symbols of death, but also hope and assistance, as they fly Harry, Luna and the others to the ministry when Harry believes his godfather Sirius to be in danger. The thestrals provide foreshadowing for Harry’s godfather Sirius’s death at the ministry, indicating that it is Harry’s journey itself that brings about Sirius’s death, that his journey there condemns Sirius rather than saving him, as he is only ever in danger when he goes to try and rescue Harry. Just as the thestrals illustrate that physical appearances and our natural belief that death is to be feared above all else can be misleading, so they also underline the plot of the film where the appearance of the rescue mission is misleading in being actually quite the opposite.

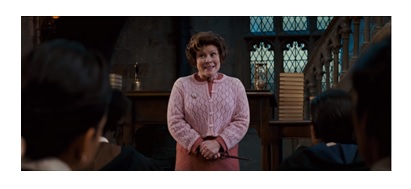

The thestrals therefore occupy a contradictory position as both creatures which can offer gentle assistance whilst also foreshadowing and being intimately assosiated with great harm. This is the kind of complicated nuance which Professor Umbridge cannot stand. Imelda Staunton say of Umbridge that ‘she doesn’t want chaos, she wants it all clean and neat and tidy, and sort of cleansed, the most terrifying word’.[1] She is intolerant of the different and exceptional, calling a centaur which shoots an arrow at her ‘filthy half-breed’. The porcelain plates depicting kittens wearing bows in Umbridges office are the first indication that she treats animals as adornments, for decorative purposes to suit her own schemes, in much the same way that she views people. Julie Tottmen, the head animal trainer, says about their work with Nala, one of the kittens used in the plates, that ‘we’re just teaching her to sit and look very pretty’.[2] It is this emphasis on their prettiness that makes the plates and their overuse by Umbridge so off-putting. Umbridge reduces the real animal of the cat to a purely aesthetic image. This notion of reduction is reinforced visually by the dwindling size of the plates which get gradually smaller towards the bottom of the wall. The interactions they have with animals, the cats and thestrals respectively, illustrates the complete contrast between Umbridge and Luna’s characters. In contrast to Umbridge’s focus on the cats’ prettiness over their actual substance, Luna’s interaction with the thestrals illustrates her disregard for superficial appearances and her receptiveness to the truth of the animal’s existence. It is interesting that truth is here aligned with the animal from fantasy, rather than the ‘real’ animal of the cat, because fantasy offers the heroic and imaginative resistance to the oppressive notion of reality offered by Umbridge and her regime. When Luna’s first offer of a clean and unproblematic apple as food for the thestrals is rejected, she responds to this by pulling out a chunk of unappetizing looking raw meat. She is thus promoting the thestrals enjoyment over the human convention of not carrying around raw meat loose in your bag because it is unappealing to humans. Luna is responding to the animal’s unique needs and not projecting a preconceived and human idea of what is right or ‘pretty’. Perhaps the most telling aspect of Umbridge’s relation with her plate cats is that she does not interact with them at all. Harry spares them a glance as he enters the office, which is a glance more than Umbridge. She ignores their continuous meows throughout the scene depicting Harry’s detention, just as she ignores and disregards Harry’s experience of Voldemort’s return, only acting according to her own preconceived idea of the truth as issued by the official ministry.

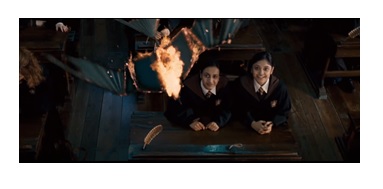

Unsurprisingly, the motif of the phoenix appears throughout ‘Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix’. In Hagrid’s hut, there is a slow zoom towards the diamond leaded windows which contain a panel depicting a bird in flight, as Hagrid narrates the need for them to prepare for the ‘storm’ of Voldemort’s return. Hagrid’s speech associates the grisaille glass bird with the order of the phoenix, with the broken diamond panes next to it indicating it’s fragility as a resistance group, and symbolizing the disorder that the movement needs to create to fight against both Voldemort and the imposed authority of the ministry. More overtly, in a scene just before Umbridge’s first class, in which she explains that she is only going to allow the students to learn the theory of defensive magic, a charmed origami bird illustrates the whimsical and unifying possibilities of practical magic that this oppresses. Padma Patil charms a piece of folded paper, blowing it into the air where it folds itself into a bird and flies over the students, who jokingly interact with it. One girl blows it upwards, Seamus Finnigan jovially swats at it, Vincent Crabbe shoots a stone at it with his catapult, and then Umbridge incinerates it. This image of the burning bird suggests the phoenix, which is associated with the hope and joy of the class, through rebirth and new life. This association is strengthened by it being an origami bird, as these are traditionally seen as symbols of hope and peace, originating from the Japanese legend of 1000 cranes, in which anyone who folds 1000 cranes receives a wish.[3] Its destruction, therefore, captures how Umbridge’s actions go beyond the usual teacher’s quelling of idle dissent to maintain classroom order, to representing her intolerance for any kind of resistance to authority and hope for change, including political dissent like the order of the phoenix.

The students light-heartedly laughing together at this origami bird also emphasises the contrast between this genuine joy from having fun with others, and Umbridge’s manic smiling and laughter at the thought of oppressing others. For example, Imelda Staunton’s incredible disturbing grin at the word ‘severe’ as she says the consequences for not studying hard ‘may be severe’, portrays Umbridge’s personal glee at the idea of students being punished. The camera follows the bird’s path, staying at a height looking down as the bird spirals onto Padma’s desk, singed and blackened. As it falls, the tentative, meandering wind instrument theme which accompanied its flight fades gently out, and there is a sudden jump cut to Umbridge standing in the doorway pointing her wand. This cut, from the high angle above the students to the low angle in front of Umbridge, with her head at the top of the frame, prefaces the scene which then commenses, in which she lowers their expectations for the class, and restricts their engagement. Umbridge’s theme then starts to play, and continues at a fluctualting volume throughout the scene. This theme is very stacatto, repetitive and relentless, creating the impression of Umbridge as a relentlessly irritating figure, imposing her own strict melody onto the freer wind instrument tune assosiated with the bird and the students.

Harry’s exposure to the thestrals fosters in him a greater tolerance for difference and the ability to look past appearances. In contrast to this, Umbridge is shown to be overly concerned with superficial appearances, as the walls of her office covered in the cat plates indicate. These cats in their circular displays are the polar opposite of the thestrals which are free to stretch their wings across the length of the frame. This portrayal of the thestrals indicates that it is admirable for Harry and Luna to find hope in these outwardly sinister creatures, and perceive them for what they really are. Umbridge’s narrow-minded outlook, in comparison, which causes her to surround herself with the cat plates over real animals, which she regards with contempt, contributes to her portrayal as villainous and oppressive.

Bibliography

Beser, Ari, ‘How Paper Cranes Became a Symbol of Healing in Japan’, National Geographic (2015) <https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2015/08/28/how-paper-cranes-became-a-symbol-of-healing-in-japan/#disqus_thread> [accessed 14th May 2018]

Staunton, Imelda, ‘Imelda Staunton (Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix) Interview 2007’, Tribute.ca (2007)

<https://www.tribute.ca/interviews/imelda-staunton-harry-potter-and-the-order-of-the-phoenix/star/24212/> [accessed 14th May 2018]

Warner Bros. Studio Tour London, ‘Training the Twitter Litter – Warner Bros. Studio Tour London – The Making of Harry Potter’, YouTube (2013)

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7JzeQ51CXlc> [accessed 14th May 2018]

Yates, David, dir., Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (Warner Bros. Pictures, 2007)

Further Reading:

Backshall, Steve, ‘Care of Magical Creatures’, Harry Potter – A History of Magic (London: Bloomsbury, 2017)

‘Life Lessons and Themes: All Sorts of Lessons’, Alohomora! A Global Reread of Harry Potter (2017) <http://alohomorapodcast.com/episode-214-life-lessons-themes-all-sorts-of-lessons/>

Rowling, J. K., Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (London: Bloomsbury, 2003)

[1] Imelda Staunton, ‘Imelda Staunton (Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix) Interview 2007’, Tribute.ca (2007) <https://www.tribute.ca/interviews/imelda-staunton-harry-potter-and-the-order-of-the-phoenix/star/24212/ > [accessed 14th May 2018]

[2] Warner Bros. Studio Tour London, ‘Training the Twitter Litter: Warner Bros. studio tour London – The Making of Harry Potter’ YouTube (2013) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7JzeQ51CXlc> [accessed 14th May 2018]

[3] Beser, Ari, ‘How Paper Cranes Became a Symbol of Healing in Japan’, National Geographic (2015) <https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2015/08/28/how-paper-cranes-became-a-symbol-of-healing-in-japan/#disqus_thread> [accessed 14th May 2018]