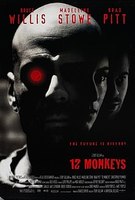

Twelve Monkeys begins: human beings whoop and rattle in cages, buried deep underground. Wild animals roam free in the streets; in the churches, on top of this underground prison. But who dug the hole? The animals or the human…

…beings? The deadly virus which forced the survivors to flee underground came from the animals. But the mass spreading of the virus was caused by the huma…

…beings’ animal experimentation. The plot centres around a specific caged hum…

…being – Cole. In an attempt to create a cure, the scientific hierarchy of this underground society force Cole to go back in time to gather information about the hu…

…beings who are believed to have released the virus – the Army of the Twelve Monkeys. Whilst back in time, Cole discovers that the Twelve Monkeys are not the h…

…beings to blame for the epidemic – it is Goines, who was expelled from the Twelve Monkeys, and his father who are to blame for the destruction of…

merge clarity as police officers shoot Cole to death whilst he attempts to kill an employee of Goines’ father, Dr Peters. Peters gets away and is met on the plane by one of the scientists from Cole’s underground prison.

…beings. Beings now whooping and rattling in their cages. The incorporated genre, surrealism, allows the audience, at times, to perceive a distorted reality. The plot follows Cole – the audience is placed within his mind – we see what he sees. We witness his flashbacks…

…we hear the voices in his mind…

…we feel his dizziness through

disorientating camera shots…

Frequently interwoven surreal experiences provide the audience with an expectation of continued surrealism – we look for it. Therefore, when the humans rattle and whoop in cages, our expectations are affirmed; instead of seeing humans the film wants us to see primate animals. I intend to explore and argue the reason why the film creates an animalised representation of the human protagonist – Cole.

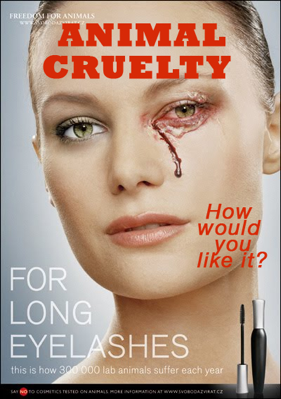

Animal testing is the primary issue of the film – the key factor which determines the plot. In spite of this, visual examples of vivisection are rarely incorporated… or so we think…

Laboratory animals are caged…

…Laboratory animals are strapped down, made to “volunteer”…

…Laboratory animals are experimented upon…

…Cole is subjected to vivisection.

Political theorist and ethicist, Alasdair Cochrane, says:

“On the one hand, proponents of animal experimentation point to the incredible benefits that humans are claimed to receive from experimenting on animals and conclude that such experiments are absolutely essential for human well-being.”[1]

Ultimately, those favouring vivisection see the benefits it has upon humanbeings.

“Those opposed to animal experiments, on the other hand, point to the enormous levels of suffering that such experiments inflict on animals and provide gruesome details of practises within the laboratory that create incredible distress to millions of sentient beings.”[2]

Ultimately, those against vivisection see the negatives it has upon living beings.

For those who differentiate human beings from all living beings, barriers to empathy inhibit the interpretation of animal testing as immoral. Therefore, through implementing treatments of vivisection upon a human protagonist – we are all forced to “volunteer” our empathy.

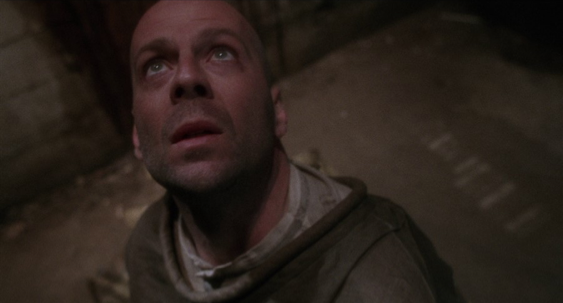

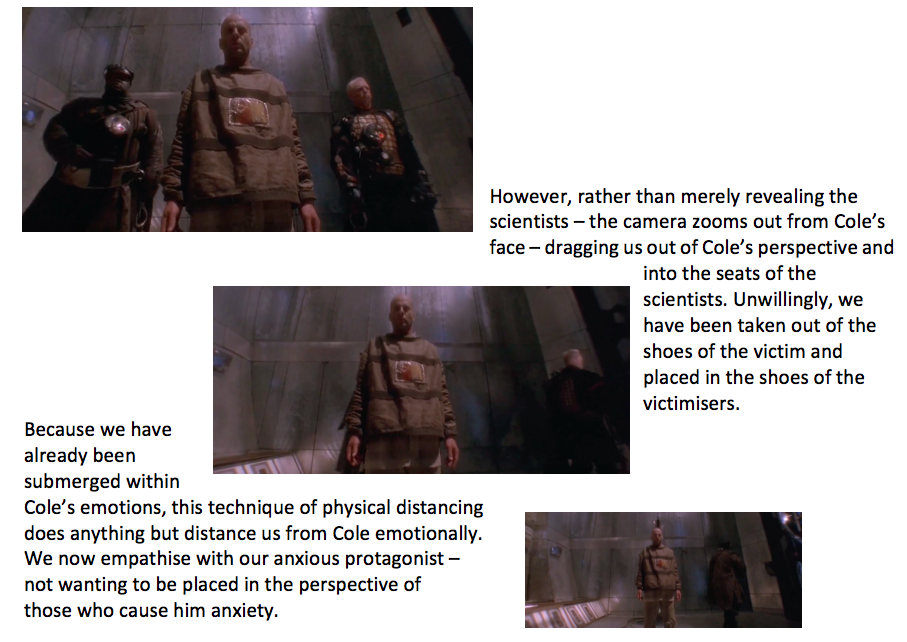

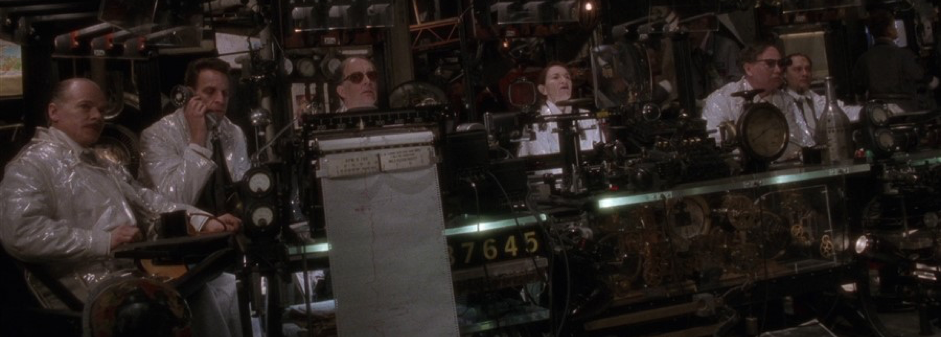

Close-ups of Cole’s face place us in his perspective so we intimately witness his reactions to his suffering. We are first introduced to the scientists through a close-up of Cole’s face, rather than being shown the scientists themselves as they speak. Therefore, Cole’s facial expressions determine our initial opinion of the scientists…

Cold. Fixed. Wary. This expression evokes our own wariness about having the scientists’ identities revealed to us.

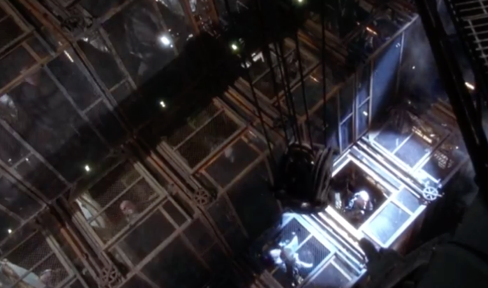

Zooming out from Cole in isolation, however, would have distanced us from Cole emotionally. Pulling us away from noticeable details of human expression – pulling us behind the objectifying observing machines – the shot would have given us “a conquering gaze from nowhere”[3]. Professor Donna Haraway uses this term to argue that scientists’ visions of their subjects become obscured when they are studied through the barrier of machinery, leading to objectification…

Seeing Cole through this lens would have made it easier for us to reject human empathy and tolerate his suffering… if it were not for our prior immersion within his emotions. The film doesn’t place us within the scientists’ view of Cole to provide us with blissful ignorance. The film does this to provide us with an awareness of the scientists’ blissful ignorance – to interpret this ignorance as wrong.

If we struggle to see a human consumed by the tortures of science – then why can we ‘stomach’ a non-human animal being treated in this way?

Cole is sent back in time and instructed to bring back evidence that could help the scientists find a cure for the epidemic. So, when Cole takes hold of a spider that he sees on the window… with no container to keep it in… we realise that the only place he can keep it is his stomach. However, rather than evoking our sympathy towards this poor, fellow, sentient being, about to be gobbled up by a ginormous beast – we are instead made to feel sorry for the human who has to do the dirty work of gobbling it up…

After a split-second of recognising the spider’s existence, Cole encloses the spider within his hands; with hardly a glimpse of the spider’s reaction. Instead, the focus is on Cole’s reactions. We see his distressed expressions… we feel concerned when Goines concurrently talks about germs… we hear the exaggerated ‘gulp’ sound effect (which if not making the spider’s death seem comical – certainly emphasises Cole’s experience of eating the spider over the spider’s experience of being eaten)…

When we watch an ‘I’m a Celebrity’ contestant eating a spider, we are also shown how the human reacts; not the spider. That’s where the gripping, emotive, edge-of-your-seat-sitting entertainment is! What would be the point in showing us the spider’s feelings? We’d never get trapped in a glass and eaten alive for a television game show. We can’t empathise so we don’t care. This is why ‘Twelve Monkeys’ uses a human rather than an animal protagonist to present the immorality of vivisection. We need a protagonist whose feelings we’ll bother to consider – someone who we can empathise with – someone to make us care.

Ferne McCann herself realised that to show what she did was wrong she must present a humanised version of a spider… even though her means of redemption was murdering more innocent animals…

But animals must evoke human empathy to some extent. Otherwise, there’d be no dog shelters… no RSPCA… no ‘Twelve Monkeys’ showing us animal testing is wrong. Therefore, my interrogation into Terry Gilliam’s decision to use a human protagonist to explore the cruelty of vivisection proceeds…

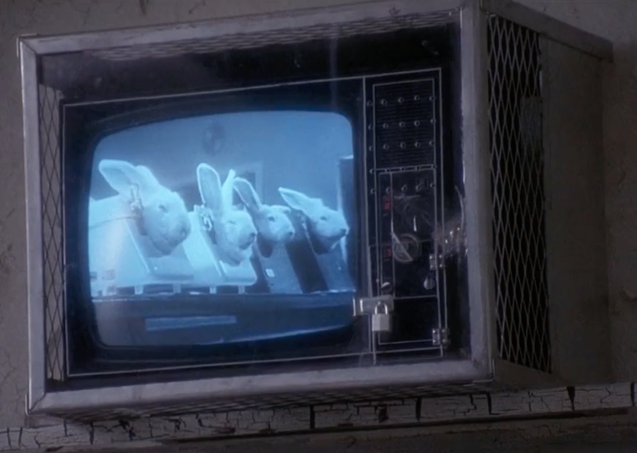

Even Cole (despite his lack of sympathy for the spider he gobbles up) shows concern for some rabbits who are subjected to vivisection on television:

“Look at them”,

Cole says – acknowledging

the human scientists,

“They’re just asking for it.

Maybe the human race

deserves to be wiped out.”

So why does Cole recognise

the mistreatment to these

rabbits yet not his mistreatment to the spider?

In my investigation so far, the commonality which seems to evoke human empathy is expression. The scientists hide behind machines to distance themselves from Cole’s emotional reactions. Furthermore, it is Cole’s expressions, when eating the spider, which allow us to interpret his distress. When a scientist injects one of the rabbits through its nose – the rabbit cowers and shivers. Ah! An expression relatable to a human. If someone injected something up our noses – we may cower and shiver in a similar way. Therefore, the more similar we are to an animal, the more we empathise and sympathise when it is mistreated.

When we zoom-in on Cole’s face we recognise and relate to emotion and suffering more than if we zoom-in on a rabbit’s face:

All non-human animals differ from us in some way. So, when we see an animal suffering it is easy for us to switch off our empathy and find an excuse for our ignorance. Through visually fragmenting the subject into individual body parts we can absent the animal from moral consideration. We see fur… claws… a tail… and the animal becomes an ‘other’; an object. Animal rights advocate, Carol Adams, refers to this form of objectification as “fragmentation”/ “dismemberment”[4]. Adams also talks about Joseph Ritson’s concern with the dismemberment of texts reflecting the dismemberment of animals. Ritson believed that just as it is wrong for an editor to dismember and alter someone’s literary work – it is wrong to dismember and alter an animal. “He became enraged at dismembered texts and dismembered animals”[5]. It’s interesting then that through dismembering his own text, Gilliam also dismembers his own protagonist. When the scientists attach Cole to the time machine – rather than incorporating one long wide shot, the film quickly cuts between close-ups of different parts of Cole’s body. This reflects how the scientists view Cole – only seeing the parts of his body pertinent to their scientific study; the scientists quickly look away when they have completed their task…

Attach its finger to the machine…

Inject its arm…

Attach its neck to the machine…

The camera shots present Cole from the scientists’ perspective – dismembered. However, Cole is human so we empathise with his expressions and reactions more than any other laboratory animal. We see his hand flex as they attach his finger to the machine… we see his arm tense as they inject him… we see his eyes close as they attach his neck to the machine. These emotional reactions are recognisable within our own behaviour. Cole is like us – human. We wholly “understand and share [his] feelings”[6]. This is the definition of empathy. Therefore, rather than the close-ups of Cole’s individual body parts detaching our emotions from him – they instead zoom in on and highlight his emotional reactions. Not only are we made to heighten our consideration of Cole’s emotions – we are shown how the scientists reject a consideration of Cole’s emotions. We are shown that the scientists’ perception of Cole – that all scientists’ perception of laboratory animals – is wrong.

Gilliam realises that in order to raise our concern for laboratory animals we must feel empathy, and to evoke our empathy, we must witness human-like emotions. In order to raise our concern for laboratory animals we must therefore imagine ourselves aslaboratory animals.

In the same way that Cole and vivisection animals “volunteer” themselves to scientific subjection – we must “volunteer” ourselves to empathetic subjection, when we watch this film.

Franklin J. Schaffner’s Planet of the Apes is another example of a film which incorporates animalised human characters to depict our immoral treatment towards animals. Another correspondence between both films is the importance of emotion to evoke empathy. When we witness Nova and Taylor being torn away from each other; locked in their separate cages – we see the sadness and longing in Taylor and Nova’s eyes – relatable, sincere expressions. Taylor makes a joke, attempting to create an emotional attachment to fill their physical distance. Taylor and Nova smile – a relatable… not so sincere expression. Nova achieves a physical smile with her mouth yet fails to convey any emotion through her eyes. In the same way we teach pet dogs to sit, Taylor realises that he “taught [Nova] to smile”[7].

Although Nova possesses a human form – she doesn’t possess human intelligence – she’s an animal. We root for Cole to escape his restrictive zoo-like prison because we see a human that doesn’t belong there. However, it is difficult for us to root for Nova to escape her zoo-like prison because we do see an animal who we have been conditioned to believe does belong there.

Twelve Monkeys shows us that “the future is history”.

Planet of the Apes warns us that history could be the future.

Suggested Further Reading

Adams, Carol, The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist Vegetarian Critical Theory (London: Bloomsbury, 2010).

Bernstein, Mark, The Moral Equality of Humans and Animals(Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

Cochrane, Alasdair, Animal Rights Without Liberation(New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

Garner, Robert, The Political Theory of Animal Rights(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005).

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), pp.575-599.

Lashmet, D. (2000). “The Future is History”: “12 Monkeys” and the Origin of AIDS. Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, 33(4), pp.55-72.

Bibliography

[1]Alasdair Cochrane, Animal Rights Without Liberation(New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), p. 52.

[2]Ibid, p. 52.

[3] Donna Haraway, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies, 14.3 (1988) 575-599, (p. 581).

[4]Carol Adams, The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist Vegetarian Critical Theory (London: Bloomsbury, 2010), p. 85.

[5]Ibid, p.85.

[6]‘English Oxford Living Dictionaries’ (Oxford University Press, 2018) <https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/empathy>

[7]Planet of the Apes, Franklin J. Schaffner (20thCentury Fox, 1968).