ZooScope ZOOM: The Wild

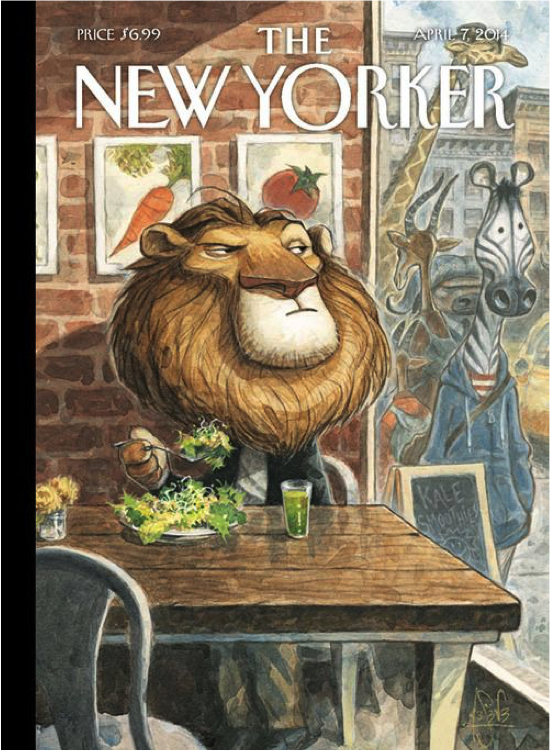

Above: ‘This isn’t Happiness’ – 07/04/2014 front cover illustration of The New Yorker by Peter DeSeve shows a vegetarian lion eating salad whilst looking distractedly at a zebra. Living in a world of cultural ethics clearly has its difficulties for a wild predator. Image from https://uk.pinterest.com/kmeyer/peter-deseve/

‘The core paradigm of many narratives engaging with nature and culture […] is largely based upon a construction of the natural world as wild and the recognition of culture as a model of apparently civilised social order,’[1] states Paul Wells upon the ‘naturalcultural,’ the animated world of animals. The problems created by encasing wild animals within a cultural model, i.e. as anthropomorphised characters in family films, renders them as displaced representations of creatures somewhere between ‘wild’ animals and culturally moral ones. Such displacement is evident through the conflicted nature of Disney’s The Wild’s morally divided lion and is directly challenged through the bamboo bathroom scene. Pulling across the bamboo curtains to reveal Colin the hyrax sitting in a bamboo bathtub, Samson ‘The Wild,’ the star attraction at New York Zoo, intrudes on a space jarringly displaced from the otherwise naturally ‘wild’ surrounding scenery he finds himself lost in. Colin’s bathroom – in part ‘natural’ (being made of bamboo) and partly a figure of first-world cultural ‘civilisation’ (being a bathroom) – epitomises a bleeding through the line between the binaries of human culture’s civilisation and the animalistic brutality of nature. The contradictory elements of cultural bathroom made from natural bamboo symbolise the conflicted forces of the natural/cultural binaries internally manifesting themselves within Samson as a result of his physical contradiction as a genetically wild, carnivorous predator born and raised in the cultural environments of zoos and circuses.

Above: Samson reaches out to open the bamboo curtain and unleash the ‘domesticated’/‘civilised’ culture and ‘wild’ natural binaries.

Despite the ability to communicate between different species as equals, animals in The Wild do not question the food chain’s hierarchy. Unlike him, Samson’s zoo friends were born in the wild and, bizarrely, are excited to witness the death of Colin, a fellow herbivore: ‘excellent. We get to see the legend in action!’ exclaims Nigel the koala. Only Samson, born in domesticity, possesses the sensibility to reject the notion of hunting, demonstrating that such a troubled morality can only be produced in an animal raised in civilised culture. However, due to his genetic foundation as a carnivore with an evolutionary need to consume meat for survival, Samson’s refusal to kill Colin sees him establish himself as a creature displaced from both the wild and the ethics of civilisation. Like the blurred binaries of the bamboo bathroom – neither entirely natural nor cultural – Samson’s own identity is muddled.

Above left: ‘The horror!’ Above right: Samson doesn’t share Nigel’s enthusiasm for his killing of and eating another animal.

It’s no mistake that Samson’s attempt at using his wild animalistic ‘instinct’ to track his son, despite being in the midst of Africa, mistakenly leads him to the culturally familiar object of a bathroom. Colin’s exclamation of ‘doesn’t anyone knock anymore?!’ sees cultural etiquette interrupt the wild ambiances; the audience automatically associates Colin as naked through the familiarity of the bathroom, despite acknowledging that animals are constantly in the nude throughout the film. Both the bathroom’s presence and Colin’s culturally recognisable exclamation during the utilisation of Samson’s ‘instinct,’ amidst the replicated realism of the animated jungle scenery, disrupts any notion Samson may have of reconciling the features of his wild, feral self. Despite being a wild animal, Samson’s lack of animality is exposed when using his natural ‘instinct’ leads him back to the safe security of the bathroom, exhibiting both his discomfort in a wild setting and displaying his dependence on civilised culture for his survival needs. This is the very culture that is the cause of his loss of animal instinct, yet he is still biologically trapped in the form of a predatory animal.

Above: ‘Doesn’t anyone knock anymore?!’ – the first words we hear from Colin.

The bathroom simultaneously works backwards by also reminding Samson that although he cannot correctly track animals using his physical ‘instinct,’ or kill through his own mental sensitivity, he cannot escape his foundation as a carnivorous species. As his attempt at killing Colin takes place within the space of a cultural area, the serenity of Samson’s zoo home is disrupted when we are reminded that, as a predator, and though he doesn’t confront them face to face, in a cultural space he still eats animals with which he can converse with. He may be unable to physically kill another animal, yet he is still capable of eating one if pre-prepared in steak form for him. Samson cannot partake in the animalistic activity of killing, but he can eat meat in a culturally acceptable form.

Above left: At home in New York Zoo, Samson smiles as he is presented with a pre-prepared rabbit steak.

Above right: A comparable shot of Alex the lion from DreamWorks’ Madagascar eating steak in captivity. He will face similar ethical complications to Samson when, finding himself hungry in the wild, he realises steak is made from animals that are otherwise his friends in captivity. Film still from https://dreamalittledreamworks.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/screen-shot-2012-08-26-at-12-19-03-am.png?w=450&h=237

Unlike Samson, Colin moves like a human, walking on two hind legs and using arm-like gestures with his forelegs. Like the intermingling of natural ‘bamboo’ with the cultural ‘bathroom’, Colin’s animation constructs him as an intersection of two separate binaries. Confronting Samson with the torment ‘it’s a lion with moral issues!’, the space of the bathroom and Colin’s inclusion within it reminds Samson that being a truly wild lion comes exclusive of morality in a world of animation where species of predator and prey can interact with one another. Even if Samson does not kill other animals himself, he still eats them as a result of his genetic biology, thus rendering his ethical ideology somewhat complicated and just as confused as the intermixed binaries involved in the construction of a bathroom in the centre of the jungle.

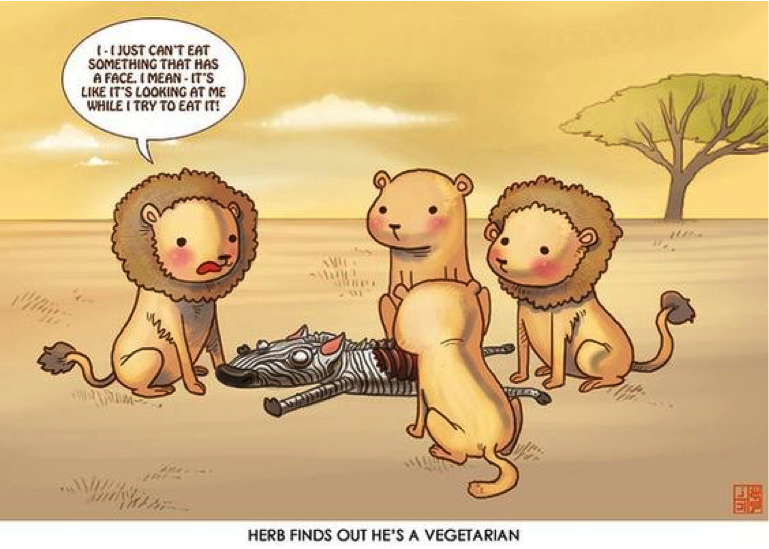

Above: ‘Herb finds out he’s a Vegetarian’ – Like Herb, Samson’s cultural conditioning and etiquette means he is only happy to eat pre-prepared meat that no longer resembles a fellow animal. His upbringing essentially ‘bubble-wraps’ him from the process of how steak is created and the reality of what it actually is, leaving him unable to hunt for himself. Image from https://uk.pinterest.com/pin/205758276694974901/

Regardless of whether he chooses allegiance to the binaries of nature or culture, Samson finds his very being inescapable from his own biological nature. Being neither a wild, mindless predatory killer, nor a domesticated, moral (by diet) prey animal, but a meat-eating carnivore who cannot face killing his meat himself, Samson’s existence within both the binary worlds of nature as a result of his genetics and culture as a result of his upbringing renders him trapped within a dislocated space between the two binaries: the bamboo bathroom itself.

YouTube video of the scene focused on in this ZOOM article: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8IDx0DnFwcQ

Filmography

- The Wild dir. Steve ‘Spaz’ Williams. Disney, 2006. (Clip time 38.20 – 41.25)

Bibliography

- Wells, Paul., ‘Introduction: The Madagascar Problem,’ in The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons and Culture (New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press, 2009)

[1]Paul Wells, ‘Introduction: The Madagascar Problem,’ in The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons and Culture (New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press, 2009), p. 19