Ariel, a headstrong 16-year-old mermaid, has dreams of living as a human on land, despite her father, King Triton’s, constant reprimands regarding her desire for human/animal (mermaid) interaction. With the help of her friends, Flounder (a loyal, although cowardly, tropical fish), Sebastian (a red Jamaican crab and servant of Triton), and Scuttle (a foolish seagull and supposed expert of humans), she attempts to learn about the human world. Disobeying her father yet again, she swims to the surface and becomes instantly infatuated with Prince Eric, a human. Ursula, the half-human-half-octopus Sea Witch, turns Ariel human for three days in exchange for Ariel’s voice, to woo Eric. Despite the mutual affection, interventions cause Ariel to return to her mermaid form. Upon realising how much she cares for Eric, Triton turns Ariel back into a human and she marries Eric, their boat sailing off under a rainbow as the merfolk wave them off, the two worlds harmonious at last.

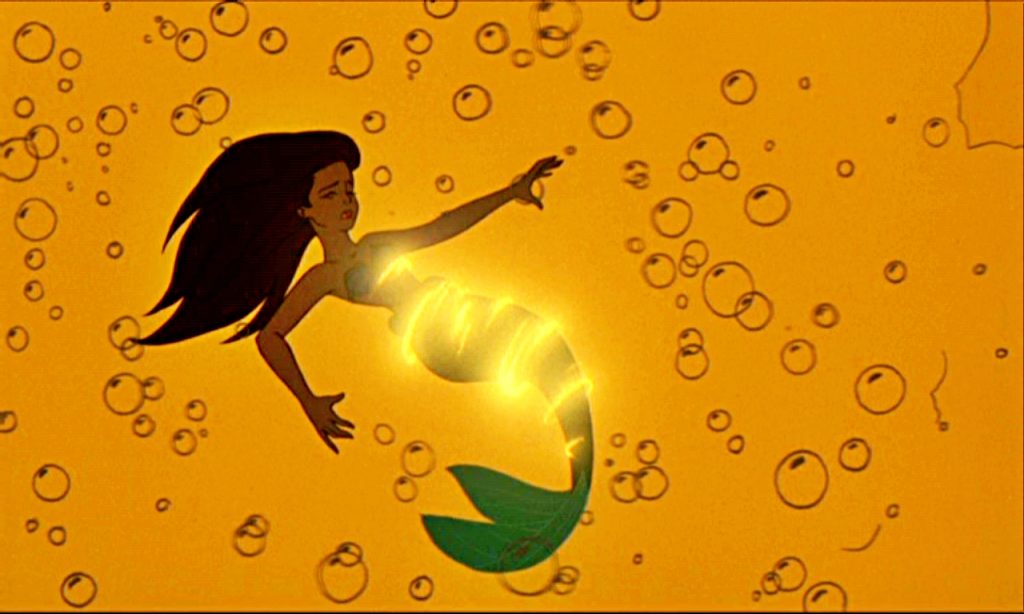

The coming-of-age genre is particularly prevalent in The Little Mermaid; by breaking the rules and questioning who she is, Ariel literally finds her legs in the world. In her underwater life she interacts only with animals, forbidden to have any contact with humans, or as Triton tactfully calls them, “fish-eaters.” Being a family film, it is significant that the adolescent protagonist defies her father; she attempts to breach the human/animal divide, which is firmly set in place, when she rescues Eric from a shipwreck. Her infatuation sees her choose to abandon her animal half and become fully human in order to marry Eric; this physical transformation marks her finding her independence and becoming an adult. The fantasy element is what makes this possible – Ursula’s magical abilities transform Ariel into a human, in which her tail is split into two legs, her fins becoming feet. By using the form of animation the animals are easily able to be anthropomorphised, and aspects of colour, sizing and lighting can easily be altered in ways impossible in other forms of animal-in-film portrayal, such as documentary.[1]

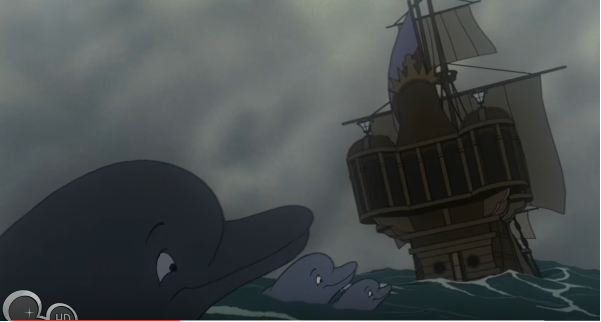

The human world/animal world divide is clearly set from the start of the film. The opening scene sees dolphins happily swimming and seeming to communicate (thanks to their animated anthropomorphism) until a ship cuts through the water, the low angling of the camera emphasising its intrusiveness into the idyllic scene, and causing them to disperse.[2]

Physically, this act shows the human world literally entering the animal world, and the animals’ negative response to this. The colours of the scene are largely grey and white, including the animals (the seagulls, dolphins and dog), and the lighting is dark, giving the whole scene a dull aesthetic. When compared to the vibrant ocean scenes later, the human world seems to be the less desirable environment to live in. The boat is also fishing, hauling nets of identical fish from the water on board. Their expressions and colouring make the fish in the pile indistinguishable from each other as a sailor throws them from the net to a barrel, reflecting the way in which humans commonly see fish on land: indistinguishable, and in this case, purely as a commodity.

One escapes from the boat, and in an imitation of a tracking shot, the camera follows it into the ocean. Upon hitting the water, it becomes even more anthropomorphised; we can detect the fear, then relief, on its face, largely due to the eyebrows it has been provided with by the artist. This characterises it, separating it from the pile of fish previously seen on land in the barrel, contesting the view that they are all identical. “The viewer is thus encouraged to empathize with the fish and to cast an estranged eye on the normal human practice of exploiting the ocean’s potential as a food resource.”[3] A series of continuity cuts follows the fish deeper into the sea. As it progresses the music becomes richer in depth orchestrally, and the ocean shots increase in brightness and colour in comparison to the land shots. The movement deeper into the ocean, and deeper into the animal world, in time with the increased visual and verbal stimuli of the setting shows the ocean to be a more exciting world to live in than the human world.

As this animal world is shown to be superior to the human, it is understandable that the animals be protective of it; we sympathise with King Triton’s guidelines forbidding Ariel to leave the ocean for fear of her being killed by a human “fish-eater.” This insinuates humans are barbaric, killing to eat the characterised animals we have already built an emotive connection to. Though this message is somewhat serious, in a true Disney animation family-fun style, the animals when on land, rather than facing harrowing threats, are incorporated into a series of puns and slapstick style comedy regarding becoming food sources.[4]

One human character that breaches the human/animal divide is Eric. He is first introduced onto the screen alongside his beloved pet dog, Max, who he is later seen to risk his life to rescue. He then proceeds to rescue Ariel, in her animal form, from Ursula. By bridging this gap between Triton’s laws of human and animal boundaries, Eric marks the human world’s attempt to harmonise with the animal; a gap Ariel is trying to connect from the animal world to human. Though this “could be read as playing out a longing for some form of resolution between the nature-culture divide,” [5] I argue it is a biased attempt, it being significant that Ariel must abandon her animal-ness in order to do this whereas Eric does not have to become any less human.

Ariel’s motive is to become human – she states her resentment at living underwater, dreaming of having legs and being on land, even before falling in love with Eric. Her desire to abandon the animal half of herself is reflected in her attitudes towards the other aquatic animals. During her first meeting with Ursula she flinches at and pushes away one of the octopus tentacles, but allows her to leave her human arm around her. Also, her closest friends are sea life with the ability to speak; others (such as the shark that chases them) do not have this human quality. It would seem that she only wishes to associate herself with sea animals possessing human qualities, meaning she is able to engage with her human half more than her animal, potentially as a way to cope with the resentment of the sea creature half of herself.

Ariel remains in an animal/human state until the conclusion of the film, when she becomes fully human. This is largely marked through her varying abilities of communication. As a mermaid Ariel has human and animal traits, but when she is first on land as a human she has no voice; in discarding her animal body she has to sacrifice her human voice. This inability to speak forces her to retain some form of animality, aligning her with the land animal, Max, who can also only communicate via body language. However, as a human, being unable to talk to animals also separates her from them, reinforcing her role as human. Her animal-ness is muteness during her first time on land, though her animal friends can speak, and she can understand them. When she returns to human form at the end, with her voice, she is removed of all of her animal qualities. This is marked by the total absence of speech between her and the animals, just the physical actions of caresses and kisses. Even when she says her only line as a human at this point (“I love you, Daddy”), we don’t see her mouth moving, meaning it could be a voiceover type thought, rather than a verbal communication with Triton; an animal. Human/animal verbal communication is very one-sided in the film, showing animals understanding humans, but humans (for the majority) unable to hear animals.

The film uses a number of techniques to make the audience sympathise with the animal world instead of the human, so the conclusion of Ariel disassociating herself from her animal anatomy, and world, seems like a contradiction. Underwater looks more fun, vibrant, exciting and safer than the depictions of the mundane human world, particularly well argued in the ‘Under the Sea’ song. Directly contrasting this carnivalesque scene is Ursula’s song: ‘Poor Unfortunate Souls,’ after which Ariel is transformed into a human. This scene is frightening – the lighting drastically darkens, emphasising the bright flashes of orange light and puffs of smoke, and the ghoulish green smoke-hands that remove her voice. These tropes and colourings of horror suggest the act of transforming to human as negative, continuing with the film’s portrayal of the animal world being the more desirable. The transformation itself is also eerie; as she convulses and writhes, Ariel’s tail is split in half and she is at risk of death as Flounder and Sebastian rush her to the surface, being human meaning she is unable to breathe underwater. None of this trauma would have been experienced had she remained as an animal.

So, why do we want Ariel to be human, if the animal world is shown to be superior? Being anthropomorphised, we already see her largely as human, so the transformation to human seems less severe than if, for example, Sebastian had made the change. By only having to learn to navigate human legs as her alteration from being an animal suggests the metamorphosis to be fairly minimal. However, the film’s build-up of human inferiority and barbarianism contradicts us rooting for her to join Eric on land. It is the ‘Disney-style’ use of combined genres that manipulate our sentiments; “according to Disney, the most important, romantic, and meaningful events in life belong to elite individuals seeking self-gratification–no other stories are worth telling.”[6] As Triton’s daughter she is a princess, making us eager to watch the adolescent protagonist rebel against her restrictions, and even her anatomy, growing into her own individual. Her being an animal becomes somewhat irrelevant, and instead we become infatuated with the romantic events, believing that marrying Eric will unify the human/animal world divide.

Through the use of animation, multiple species of animals are able to be anthropomorphised, affecting the way otherwise incomprehensible animals are represented. Even the animals without the ability to speak are presented to the audience in a newfound way, as conscious thinking, emotive, responding creatures. The role reversal, of the animal world being more desirable than the human, increases the film’s whimsy and questions how animals consider humans. By giving otherwise mundane animals (fish and crabs) characteristics and personalities bolder and more enticing than those of the human characters, our perceptions of the animals alter. It evokes the imagination, forcing us to consider what really happens in the unseen depths of the ocean, in a “’realistically’ believable fantasy land.”[7] Bringing to film an animal world so much more vibrant than the human world allows for reconsideration of the real wonders of our planet, and how we (as humans) respond to nature, contesting our real animal/human world divide. Animation also allows for the creation of fictional animals (mermaids) to be portrayed, and how they perceive themselves – in this case, as animals, strictly non-human. This raises interesting questions about what it means to be human; is it simply the gaining of a human body that deciphers Ariel as human? If merfolk existed, would they have the ability to speak, or are they anthropomorphised as much as the real animals? Part of the charm of The Little Mermaid is its power to make us think what it would be like to live in the animal world; precisely the opposite of what Ariel wonders.

Coming-of-age animations are a staple of Disney’s film repertoire, particularly appealing to the family aspect by meeting the parents’ requirements by “incorporate[ing] a flux of complex and mature incidents and themes, the main intention… to entertain and educate children.”[8] In The Little Mermaid anthropomorphised animals interact with human characters both physically and on a cultural level, challenging the divide between human and animal environments, and the consequences of breaching the divide. Similar themes are addressed in Disney Pixar’s Finding Nemo, where the conventions of removing natural life from the ocean (Nemo) to a world of human commodity (in his case, as a pet in a fish tank) is contested, again perceiving the human world to be inferior to that of the ocean. Also, issues regarding the metamorphosis of animal to human, and the desire to achieve this, is found in Disney’s Beauty and the Beast.

Further Reading:

Andersen, Hans Christian, ‘The Little Mermaid’ HCA Gilead (1836) <http://hca.gilead.org.il/li_merma.html> [accessed 11th January 2017]

Brown, Noel, The Hollywood Family Film A History, From Shirley Temple to Harry Potter (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2012)

Whitley, David, The Idea of Nature in Disney Animation (London and New York: Routledge, 2008)

References

[1] Lee Artz, ‘Animating Hierarchy: Disney and the Globalization of Capitalism’, Global Media Journal (2002) <http://www.globalmediajournal.com/open-access/animating-hierarchy-disney-and-the-globalization-of-capitalism.php?aid=35055> [accessed 7th January 2017] (para. 4).

[2] Justyna Fruzińska, Emerson Goes to the Movies: Individualism in Walt Disney Company’s Post-1989 Animated Films, Google Books <https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=vjdQBwAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&dq=emerson%20goes%20to%20the%20movies&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=62&f=false> [accessed 7th January 2017] (p. 62).

[3] David Whitley, The Idea of Nature in Disney Animation (London and New York: Routledge, 2008) p. 41.

[4] Ibid. p. 41.

[5] Ibid. p. 40.

[6] Lee Artz, ‘Animating Hierarchy: Disney and the Globalization of Capitalism’, Global Media Journal (2002) <http://www.globalmediajournal.com/open-access/animating-hierarchy-disney-and-the-globalization-of-capitalism.php?aid=35055> [accessed 7th January 2017] para. 37.

[7] Ibid. para. 10.

[8] Paul Wells, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons and Culture (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2009) p. 77.

Bibliography

Artz, Lee, ‘Animating Hierarchy: Disney and the Globalization of Capitalism’, Global Media Journal (2002) <http://www.globalmediajournal.com/open-access/animating-hierarchy-disney-and-the-globalization-of-capitalism.php?aid=35055> [accessed 7th January 2017]

Fruzińska, Justyna, Emerson Goes to the Movies: Individualism in Walt Disney Company’s Post-1989 Animated Films, Google Books <https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=vjdQBwAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&dq=emerson%20goes%20to%20the%20movies&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=62&f=false> [accessed 7th January 2017]

The Little Mermaid. Dir. Ron Clements and John Musker. Buena Vista Pictures, 1989.

Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons and Culture (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2009)

Whitley, David, The Idea of Nature in Disney Animation (London and New York: Routledge, 2008)