“Do you think God gives a damn about miniature donkeys, Colm?” “I fear he doesn’t. And I fear that’s where it’s all gone wrong.”

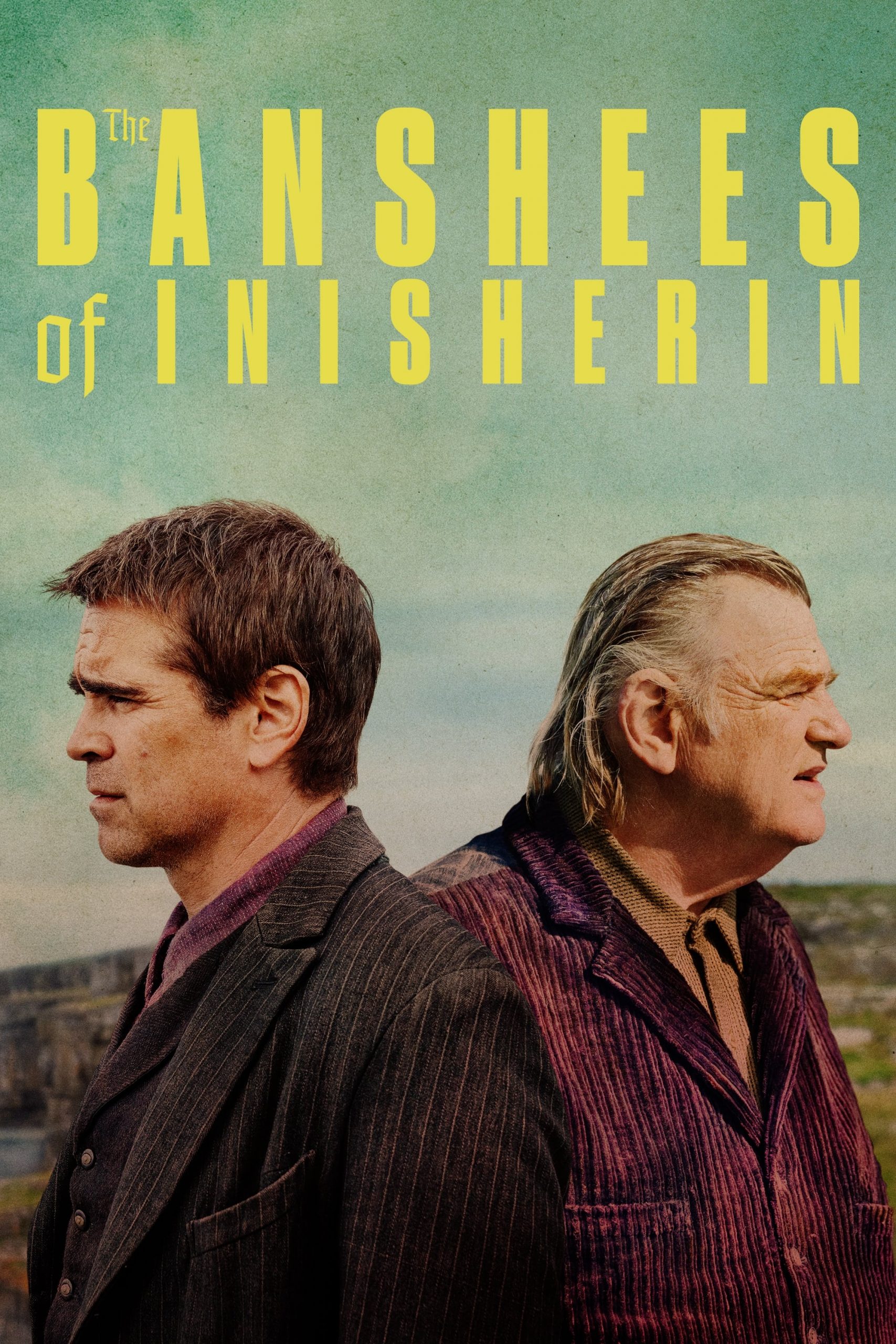

Martin McDonagh’s, “The Banshees of Inisherin” (2022), is a Tolstoyan tragicomedy combined with macabre naturalism which works to present the asperity and invaluableness of life and friendship. One significant friendship occurs between a 60 year old fanatical violinist, Colm Doherty (Brendan Gleeson) and the younger, more benevolent of the pair, Pádraic Súilleabháin (Colin Farrell). The two are familiarised in the fictional and esthetic Irish Isle of Inisherin for their frequent visits to the one pub in the town as their only commonality. Gleeson’s character displays an indignation over his existence and a morbid belief that he has precisely 12 years left to live. The adversarial representation of Pádraic and his pleasantness regarding a simple life gives the audience a sceptical yet exhilarating view into a bond full of moral dilemma. With Jenny, Pádraic’s donkey’s death following her choking on Colm’s self-mutilated finger, due to his careless, uncompromising need for freedom, an animosity emerges between the two protagonists. Through this heedless oppositional association between Pádriac and Colm, we see a pragmatic yet microcosmic view of the effects of the Irish Civil War.

Predominantly, McDonagh’s film is about friendship, but it also reveals the truth of how animals will not let you down like humans do. Every character in the film has a soothing interaction with an animal to some degree, which certainly seems intentional. Jenny, whose death is reminiscent of “The Messiah’s donkey”, aids the progressive views on what is deemed as a true companion abundantly. The animal-human relations here obscures the nature of entrapment and companionship as it is configured through repressing desire and the power of non-language; actions speaking louder than words. Animal-human relations within the film also conceptualises how different species receive altering responses from their owners. Other animals that are introduced are Colm’s dog and Pádriac’s farm animals. However the horse’s, like Minnie, were provided roles principally for transportation as it was hard for the crew to travel around the island, and the cows for the sake of realism and easement. These differing animals form a symbiotic relationship with one another and the humans through their situatedness and spiritualistic representations.

McDonagh’s choice to set the film in 1923, when the Civil War had been occurring for almost a year, is to establish the considerably logical, eventual break between Pádriac and Colm. Owing to the idea that the people of Ireland, following the Irish War of Independence also were fighting for autonomy while others were antagonistic; similar to Pádriac initially being uncomplacent to his friend’s wish. About halfway through the film, the mise-en-scène shows the bird’s eye shot of a split fork road as the pair go their separate ways following Pádriac’s pleading. McDonagh is foreboding physical distance that will continue as the roads never meet although we trustingly want them to. This follows a fast-paced cut to Colm playing his violin and admiring the view outside, to a shot of Pádriac on the floor. The contrasting reactions of the two through the separate captured moments highlights their separation. Following this, the dependable Jenny enters and nudges Pádriac’s hands and then follows him to the pub so he can seek his ‘revenge’. Not only is the donkey allegorical in this scene particularly of a calmness before the storm but she is also awarded with a level of agency. Farrell even claims to ‘The Hollywood Reporter’ that Jenny, although “never [having] had a day’s training in her life”, fits her role irreproachably. Therefore, the donkey, following the male conflict exalts the Shakespearean pity we feel for Pádriac.

The aforementioned value of Jenny is not only due to Ireland internationally deemed the home of the donkey. They were used for transporting goods and ploughing crops whereas they are also kept as pets in the modern world. Shrayer (2022) claims that it is McDonagh’s evocation of Colm’s ecclesiastic self-mutilation to Tolstoy’s ‘Father Sergius’, who cuts off his index finger which is markedly used to play the fiddle. This self-mutilation is assured as a sin by the town’s priest during a confession, to which Colm reacts with questionable disdain showing his uncompromising need for freedom. Jenny as “The Messiah Donkey” displays the primitive reactions to spirituality, and Colm’s self-mutilation as a path to seeking out solitude in his personal life, which is a Tolstoyan concept of desire. McDonagh presents this concept through the sustained shots beginning from the first mutilated finger to till the last one gradually zooming closer on Colm’s hands. This signifies the effects of male conflict blurring the distinctions between animality and humanity as the men act like animals compared to Jenny’s helpfulness; if Pádriac is under stress, she appears on screen. Many times Jenny is seen to be walking in and out of the dimly lit residency of Pádriac and Siobhan (Kerry Condon) as Pádriac pleads his sister to not leave him but the donkey walks out and nobody notices. We are aware that Jenny needs a bit of company, same as Pádriac, so she is normalised and valorised as an animal and as a companion. Perhaps, Colm should not be villainized for his changing interests in ‘boring’ discussions, especially because of his immense love for his dog who he is seen dancing with inside his home. Although he displays a lack of interest in keeping Pádriac as a companion, he is still respectful toward his canine friend.

George Eliot has stated that, “Animals are such agreeable friends—they ask no question and pass no criticisms.” which is undeniably true to McDonagh’s fictional world. This is conveyed through the simplistic cinematography focused on the littoral landscape of Inisherin. This simplism relates to how the animals are also portrayed which highlights how they are much better without domestication and in their most natural states. Therefore, McDonagh is trying to uncover the benefits of giving back to the earth by giving back to animals. Pádriac’s relationships with the people and animals is a prime example for this claim as it shows a continuity throughout the film. He is often left behind which is captured through the camera’s distance from the actor; frequent far away shots are taken when he is most distant from Colm and Siobhan. This visual design often switches to a zoom in when he is sat with the animals or having a significant tête-à-tête with said companions. These angle changes signify the allegory for the Irish War as McDonagh relates the focus on certain nature or human elements to the background of the scenes. When looking across the water from Inisherin we can detect multiple explosions happening on the coast which the characters observe from afar on occasion with the hopes that it will soon come to an end. The two protagonists’ friendship ending is what seems to be the most significant event to the townsfolk, perhaps in effort to detach from the state of affairs in Ireland. So Colm’s respect toward his dog foreshadows its reciprocated helpfulness in dragging away gardening scissors so he does not hurt himself further following an almost forgiving discussion with Pádriac.

Another shot which captures the significance of having animal companions in one scene is when McDonagh captures an unaccompanied goat with the use of a fixed camera position. This shot is held for a few moments and captures serenity against the despotic landscape, which allows the audience to ponder on if the effort we put into other members of society is worth the torment. Also it hints at when kinder people, much like Pádriac, are separate from other humans and keep animals in their company, they will not get hurt. We notably see this when Pádriac is centre stage, sitting in his kitchen near the end of the film where the animals surround him with a calm atmosphere formed through a yellow toned lighting coming from the window. Although he has lost everyone he has cared about over the duration of the film; humans fail and leave him but his animal companions do not. There are indisputable limitations on the types of relationships we form with other animals and there will be the humane urge to form connections with other people. Regardless of this, connecting with animals is an undervalued practice to avoid solitariness despite a requited incapacity to understand them to the fullest degree.

Nearing the end of the film, after Pádriac’s isolation has reached its peak, Siobhan returns through a message pleading for them to reunite through voice over. This is almost like a celestial being urging him to descend from his ideas and state. Pádriac seems to be readily packing up to escape his newfound disposition, only to be followed by a shot of him approaching Colm’s house with fuel to ignite it. Colm’s dog is found outside, starts piling logs of wood next to it with no intention to cause it harm. Pádriac takes up the focus on the screen, the camera follows his movements back and forth between the house and the flammable objects. The scene is accompanied by graceful opera music, and as we do not know if someone believed to be nice and care for animals would cause such harm, the music aids to heighten the disparity between the actions shown on screen and sin. Yet Pádriac does not let the audience down, as he removes the dog from any possible harm by placing it in his carriage, and proceeds to alight the house. McDonagh successfully portrays how the protagonists need to repent as this is followed by the sounds of church chimes going off in the distance, as Colm melancholically accepts his fate. Pádriac, again in voice over, replies to Siobhan as Colm’s dog watches him intently. He states that he will not leave as he watches the flames from afar, the focus making the house appear smaller compared to him, to show a sense of victory.

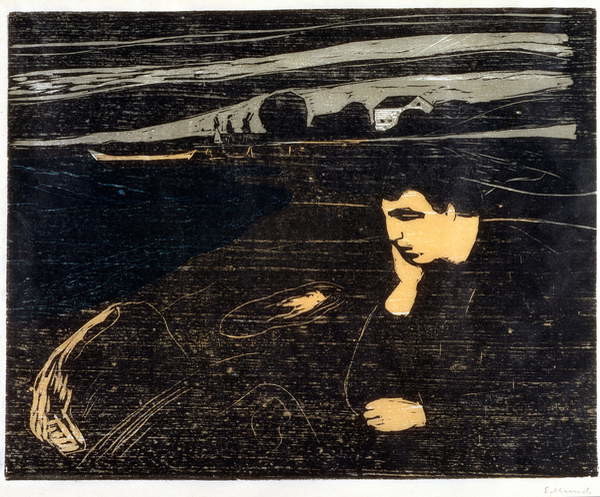

The most demanding scene to watch is the final scene as Pádriac and Colm are sitting together on the beach as Colm thanks the rejected Pádriac for looking out for his dog. This scene reiterates that having a companionship with animals is far superior to that with humans; and the need for human interaction can be more of a curse than a blessing. Pádriac relates the battle across the sea to something “you never move on from, and maybe it’s a good thing”. Colm has already moved on, and will not be able to feel the loneliness that Pádriac does, especially as his dog, who is rarely far from his side, is still alive. The casting of Morse, the border collie owned by Rita Moloney, the donkey animal handler meaning the animal characters had mutualistic interactions. McDonagh filming on location in Ireland on Inis Mor and Achill Islands meant the film could demonstrate the sublime mountains and coast of the West coast of Ireland. This scenery aids to the othering of characters, combining both serenity and the expectancy of danger. The seaside here especially is used to evoke melancholy, tension and disorder in contrast to the calmness the animals bring to the characters.

Through the comical religiousness and engaging concepts on justice, McDonagh urges the audience to question what it is meant to live and to form connections. He also shows how to connect with a being such as an animal takes diligence which can in result be advantageous. Even Siobhan, although frequently disputes with Pádriac for allowing Jenny into the house, is seen giving her a pet in the kitchen when he is not in sight. All the characters interact with the animals, meaning all of them have a use for one another. The dialogue between the protagonist and the lack thereof from the animals who communicate non-verbally but physically bond displayed through pets and walks together. The dark hue was captured through lighting and editing, which was heavily inspired by McDonagh and cinematographer Ben Davis spending time viewing oil paintings to give the background a more realistic feel. McDonagh’s choice of including ‘banshees’ in the title to cleverly demonstrate the impending death of someone through the Gaelic myth is a subtly necessary insertion. Lastly, the mostly lyricless musical choices backing the scenes, altering between evoking suspense to calmness, especially in the final scene shows how musicality can help convey feelings even when words and expressions cannot. McDonagh’s portrayal shows a naturalistic view on life and friendship to be full of conflict, which one can hope to be inconstant.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Banshees of Inisherin, dir. by Martin McDonagh (Searchlight Pictures, 2022).

SearchLight Pictures, The Banshees of Inisherin, Official Trailer, online video recording, Youtube, 4 August 2022, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uRu3zLOJN2c> [accessed 14 January 2023].

‘New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film’, Samantha Lay, ‘Good intentions, high hopes and low budgets: Contemporary social realist film-making in Britain’ (Volume 5, Issue 3) , Nov 2007, p. 231 – 244.

The Crossover, Eric Banks, ‘The Banshees of Inisherin: An Irish Morality Tale’, November 30 2022 <https://champlaincrossover.org/2282/culture/the-banshees-of-inisherin-an-irish-morality-tale/> .

Elena Rein, ‘The Sea as a Setting and a Symbol in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction’, Lund University, (2014), p. 1-67.

Sobia Tahir, ‘Tolstoy’s Ideology of Non-Violence: A Critical Appraisal’, Dialogue (Dera Ismāīl Khān, Pakistan), 7.4 (2012).

Mitchell, Peter, The Donkey in Human History : an Archaeological Perspective, First edition. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Clancy, Cara L., Laura M. Kubasiewicz, Zoe Raw, and Fiona Cooke, ‘Science and Knowledge of Free‐Roaming Donkeys—A Critical Review’, The Journal of Wildlife Management, 85.6 (2021), 1200–1213.

lakeway, Stephen, ‘The Multi-Dimensional Donkey in Landscapes of Donkey-Human Interaction’, Relations, 2.2.1 (2014), 59–77.

Emily Zemler, ‘How seaside settings evoke turmoil, melancholy and tension’, LA Times Issue, (29 November 2022).

Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, ‘The Banshees of Inisherin’ and the dark Catholic imagination of Martin McDonagh’, America Magazine Issue, (16 December 2022).

FURTHER READING

Lara Feigel and Alexandra Harris. ‘Modernism on Sea: Art and Culture at the British Seaside’, New York: Peter Lang, 2011.

Andrew Anthony, ‘Friends are good for us … so why do many men have none at all?’, The Guardian article, (29 October 2022).

Hannah Strong, ‘Meet Jenny the Donkey, Banshees of Inisherin Scene-Stealer’, Vulture Magazine, (21 October 2022). <https://www.vulture.com/2022/10/jenny-the-donkey-banshees-of-inisherins-scene-stealer.html>

Anthony Lane, ‘Whimsy and Violence in “The Banshees of Inisherin’, The New Yorker, Issue, (October 24, 2022) <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/10/24/whimsy-and-violence-in-the-banshees-of-inisherin>

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Messiah%27s_Donkey

Maxim D. Shrayer, ‘Tolstoy and ‘The Banshees of Inisherin’’, Tablet Magazine Issue, (22 December 2022). <https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/tolstoy-banshees-of-inisherin>

David Phillips, ‘The Animals of ‘Inisherin’’, Awards Daily Magazine , (11 December 2022).