When Julia Ducournau’s debut feature film Raw (2017) was shown at Toronto’s Film Festival, paramedics were called to the scene after cinema-goers fainted during the screening.

Raw tells the story of highly gifted 16-year-old vegetarian, Justine (Garance Marillier) and her journey into a merciless and dangerously seductive world during her first week of veterinary school. During a gruesome hazing ritual, Justine is forced to eat a raw rabbit kidney for the first time and Justine becomes prey to her carnal desires, which inevitably take hold of her actions and her true self comes to light. Whilst the film reigns in on Justine’s battle to suppress and come to terms with her appetite for human flesh, Ducournau floods the film with animals, whether they are alive, on the dissecting table or appearances in dreams, in order to remind us of the internal conflict Justine is going through between her animalistic urges and her desire to remain a functioning member in society.

At first glance Raw sits firmly in the horror genre, however, the film falls into numerous sub-genres. Ducournau herself states that the film is more coming-of-age than a horror film. This tale of sexuality, identity and human capability resonates well with fans of independent films, and those who are looking to chew on what they’ve seen for days after viewing. By merging the horror genre with the more light-hearted coming-of-age genre, Ducournau is able to explore taboos which are seen as inhuman in modern society, whilst also exploring ideas of personal identity and what makes us ‘human’. It is the use of animals within the film which gives Ducournau leverage in exploring this idea of human nature and identity. Being set at a veterinary school, Justine is constantly around the animal-other, and audiences are given numerous moments to compare Justine’s journey of adolescents to the animals that surround her. Therefore, Ducournau uses animals within her film to constantly remind us of the thin barrier between the human and the non-human animal.

The intra-diegetic dialogue held between Justine and her course mates opens up a space for the animal to become a sight where important issues surrounding gender, identity and the human-animal binary can play out. As a film that is fuelled by cruel heteronormative hazing rituals, where rape culture plays at large, it is interesting to note that Justine extends her views on sexual abuse to the animal body. Over the course of a lunch break, Adrien exclaims “Legally, I don’t think “monkey rape” exists […] the monkey won’t turn anorexic and see a therapist. It’s not the same.” To which Justine responds “Monkeys are self-aware. They see themselves in the mirror, right? I bet a raped monkey suffers like a woman.”[1] The close up on Justine as she projects these lines provides the audience with a detail to her connection with the animal other, it is clear that she has empathy towards the mistreated animal and understands it’s pain. The close-up also allows us to witness the rage that fuels this response. As a vet student, Justine believes it is her job to protect the animal and fight for its right. Although the animal is not present on screen, Justine evokes a sense of pain that both her and the animal shares with the possibility of sexual assault. This representation of the non-human animal through the voice of the human presents an obscurity between the binary. Thus, highlighting how both the human and the animal are at risk of being dominated against their will and being hurt both physically and emotionally hurt.

The non-human animal becomes vulnerable at the hands of the human, as it is stripped away of its animality and true identity within the natural world. The claustrophobic atmosphere, created by multiple close-up shots of the horse within the surgery room, alongside the use of diegetic sound in this scene, highlights the fear of losing a sense of identity. As the horse becomes tranquilized the diegetic sound focuses on the horse’s breathing, where once strong and powerful, its breathing becomes slow, distant and quieter. By reducing the volume of the breathing, we are almost witnessing the animal being stripped from its animality, as it becomes forced into a state where it can work alongside the humans and comply with their needs. Ducournau’s use of the camera reinforces this vulnerability of the horse as it becomes de-animalised. Throughout the sequence the horse’s eye remains the focal point, the horse is constantly staring at us and making eye-contact with the viewer. The use of the animal gaze creates the idea that ‘we are looking from within nature [and given access to a] point of entry for our engagement with the natural world.’[2] A point of communication is created, we witness what the horse feels as it views us view its downfall. This scene mirrors Justine’s journey within the film. Her animalistic, carnal and cannibalistic desires that hide within her are suppressed and forced below the surface in order to fit in with the requirements of modern society, she can never truly be herself if she wishes to fit in. As we view this scene, we become aware of the harrowing realisation that, perhaps, like the horse and Justine we can be forced to hide our true identity in order to fit in and play our role in society. By putting us in a position where we become entwined with the non-human animal’s emotions, Ducournau creates a sense of mutuality between the human and the non-human animal and points to the idea that the boundary is not as defined as we think.

The non-human animal is used within Raw to consider questions of sexual desire. In one of the pivotal scenes within the film when Justine’s sister, Alexia, gives her sister a Brazilian wax, we see her pet dog interact with Justine’s sexualised body. The camera zooms in on Justine’s legs propped up in a sexual position, however, it is her matching pink socks and underwear which represent Justine’s femininity and naivety towards the highly sexualised life that is ahead of her. As the camera zooms in we see Alexia’s dog enter from the left side of the screen and walk straight to Justine’s opening and place its head directly in between her legs. Ducournau’s use of the dog is interesting here. Dogs are normally symbols of loyalty and protection, yet within this scene the dog appears to invade Justine’s most intimate part of her body. It is almost as if once Justine is in a vulnerable position, she becomes pray to the dogs primal desires for sex. As the film surrounds itself with heteronormative rape culture, Ducournau uses the dog in this scene to symbolise the duality of man and animal, and how they both have primal desires for sexual pleasure, and how when a woman becomes vulnerable, it becomes easier to advance sexually towards her. Therefore, through the use of the animal, we see that both man and animal share desires and that they are not as different as they believe when it comes to something as primal as sex.

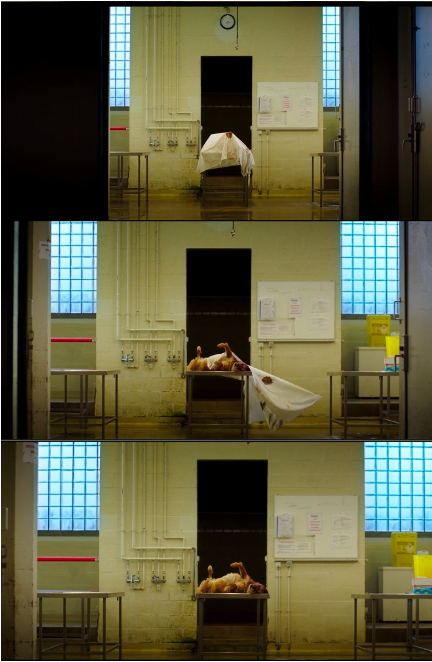

This scene, which occurs in the middle of the film, highlights how the animal within Justine has surfaced. During one of the few unnerving dream sequences within Raw we see the camera zoom in on an object covered by a bloodied sheet in a clinical space. Once the camera is at its closest point an unseen force slowly removes the sheet to reveal a deceased dog going through rigor mortis with its limbs stiffened and up in the air. The unveiling of the dog is highly symbolic within the film’s narrative structure, it signifies a moment where the animal and the human meet, where the animal awakens. It is a key moment for the unravelling of Justine’s identity; it signifies her coming to terms with her animalistic desires and no longer hiding them from herself. Furthermore, by producing this scene as one of the dream sequences Ducournau investigates the animal within. Although it may be dead, like the dog, it is always present living within us, it is dormant and waiting to surface. Drawing her audience towards the idea that the human animal binary is less prominent than we like to believe.

This scene, which appears near the end of the film, points to a site where our animal instincts dominate our desire to be part of humanity. Ducournau presents humans’ capacity for violence through her characters embodying the non-human animal. The midrange close-up presents the sisters in their most animalistic state, as they both bite each other until blood is drawn and hold on until one gives up. Ducournau is making a clear link between the animal and human and the similarity of their existence and actions. This is perhaps, as Ralph Acampora states, the ‘nonhuman and human animals share [their] experience of living in bodies’.[3] It is the one thing that they both share, our bodies are vessels for animalistic tendencies. As the scene progresses, this moment of savagery is broken by scarves being wrapped around the girls necks and pulled apart as they start clawing for freedom. This breach of humanity evokes fear in the other students as they attempt to bring back normality. Their fear is the fear of the animal inside surfacing and taking control, they enforce the idea that the internal animal is something that we should be afraid of and that it should be repressed within us. Through this scene, Ducournau states that the human and the animal intertwined with one another, and it is society’s fear of this savagery that makes humans enforce the human animal binary.

The representation of animals within Raw stresses how similar we are to our non-human animal companions, and how the binary between us is thin and highly constructed. By representing animals in a way which the audience can understand and relate to their unvoiced emotions, Ducournau is able to make a comment on wider society. By incorporating animals within her body horror coming-of-age identity film, she represents adolescents in its true natural, yet brutal, form; an age where we are both vulnerable to our surroundings and in a position where we must explore our identities and discover our untamed desires. It is not the human that speaks to the animal, but rather it is the animal that speaks to the human and raises the question of what really distinguishes the human from the animal, and what it is that makes us human. It is only through the use of animals within her film we can really dip deep into these much larger societal questions, as without a point of comparison, we are unable to distinguish identities and differences.

The film presents heavy and complex topics which are not usually displayed within the classical coming-of-age films that are widely watched and talked about. By combining the coming-of-age narrative with the horror genre and aspects of body horror, Ducournau is able to unpick these topics through taboos which offer a space for a much deeper analysis of the questions and issues she wishes to raise. By staging her film at a veterinary college, Ducournau masterfully incorporates animals into the film to pull out questions of identity, adolescence and humanity within her narrative. Raw is not for the faint hearted, its gory and provocative narrative is unsettling at the best of times, but for those who engulf themselves in Ducournau’s world, will leave the film asking questions about their own identity and humanity, wondering whether they have animalistic desires buried deep inside of them.

References –

[1] Raw, dir. by Julia Ducournau (Focus World, 2017).

[2] Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film, 1st edn. (London: Reaktion, 2002) p. 47.

[3] Margo De Mello, Animals and Society: An Introduction to Human-Animal Studies, 1st edn. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012) p. 390.

Bibliography –

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film, 1st edn. (London: Reaktion, 2002)

Ducournau, Julia, dir., Raw (Focus World, 2017)

Mello, Margo De, Animals and Society: An Introduction to Human-Animal Studies, 1st edn. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012)

Further Reading –

Stephen Prince, The Horror Film, (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2004).

Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film, (London: Reaktion 2002).

Film4, French Cannibal horror Raw | Film4 Interview Special, online video recording, YouTube, 4 April 2017, <https://youtu.be/-l76o-uoMiM> [accessed 21 January 2021].

Kaleem Aftab, ‘Director Julia Ducournau on her cannibal film Raw: ‘I asked my actor, what do you think in principle about shoving your hand up a cow’s arse?’, Independent, 5 April 2017 < https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/julia-ducournau-raw-a7666871.html> [Accessed 23 January 2021].

Nicolas Rapold, ‘RELEASE ME Healthy Appetite Julia Ducournau’s Raw’, Film Comment, 52(6), p.8