One hundred and one Dalmatians, ninety-nine of which are puppies, in a terraced house in London. How wonderful! The perfect Disney dream ending. Or in the realms of reality, a deluge of responsibility that is only going to increase if Roger and Anita, the owners, don’t begin to take spaying and neutering seriously. It is, therefore, no surprise that the demand for Dalmatians skyrocketed after the film’s 1985 and 1991 re-releases. The potent effect of the Disney charm works its magic again. Using novel Xerox technology, Disney crafts a ‘onederful’, yet problematic, depiction of pet-keeping as it follows the journey of pet Dalmatians Pongo and Perdy who, with the aid of many other animals, traverse the South England countryside in pursuit of their stolen puppies. Imbued with a spirit and agency to rival Lassie, the dogs overcome the dog-nappers to rescue and reclaim the puppies where the humans are unable to.

Helping to foster the narrative’s portrayal of the fun and fulfilling side of pet-keeping are the lively jazz score and fresh twentieth-century art style images of animated talking animals. It is a children’s Disney film after all. But, like most children’s films, there are controversial ideas lurking beneath the surface of the seemingly light-hearted representation of interspecies companionship. As well as igniting a discussion surrounding the liminality of being an animal in a human family, techniques from fast cutting to vignettes question the treatment of animals as pets in their commodification and objectification. To counter these belittling, anthropocentric views, the film empowers pets by presenting them as autonomous and active beings using methods from point-of-view shots to voice-over. In doing so, the film challenges the idea of pets as the passive agent in the human-pet relationship, showing their potential to be as capable and active as we are, if not more so.

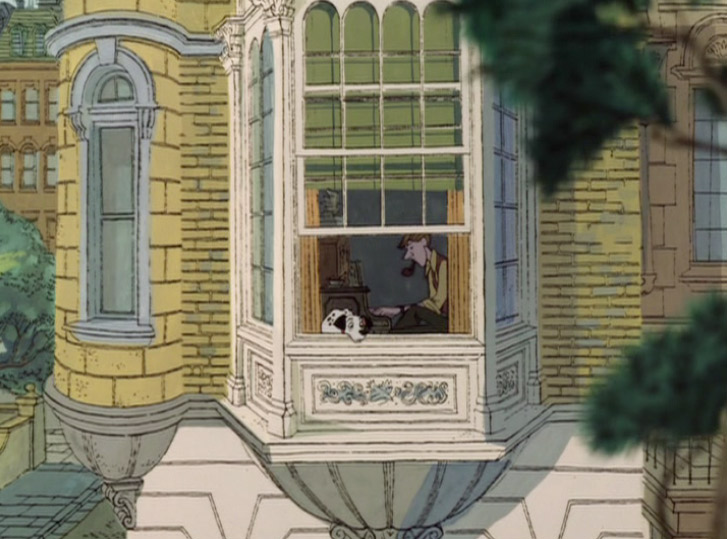

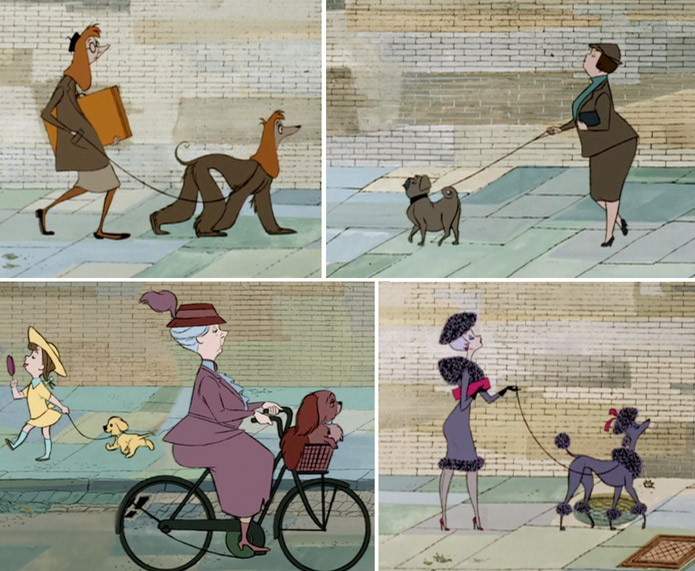

Figure 3. Dogs play an active role rather than a passive role. [3]

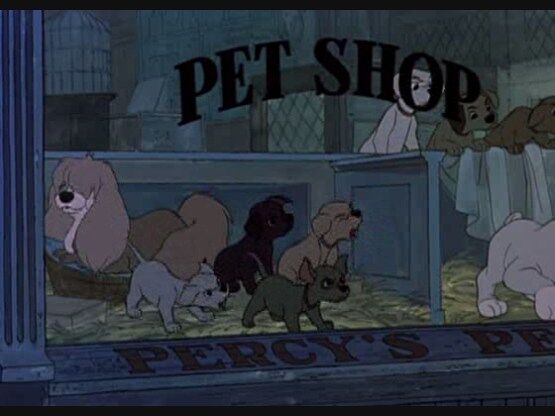

Figure 4. A person ogles a dog in a pet shop window. [4]

Cinematic animals are often ‘marginalised in relation to the main frame of human interest’, but not in One Hundred and One Dalmatians.[5] The opening scenes of the film establish the empowering of the pet and their experience by constructing the narrative through a mixture of Pongo’s voice-over narration, a zoom shot of Pongo, and Pongo’s point-of-view tracking shots. Beginning with a full shot of the mise-en-scène, the camera proceeds to zoom in on Pongo in a window with his human owner, Roger, in the background. By foregrounding Pongo and placing Roger in the backdrop of the mise-en-scène, the human experience is visually relegated and the pet’s experience is promoted. Roger’s placement behind Pongo in the mise-en-scène demonstrates how humans mainly serve as supporting acts of the dogs’ story. The camera focusing on Pongo combined with use of Pongo’s voice and use of Pongo’s visual perspective to craft the story bestows an authority on the pet, as opposed to the human, that continues throughout the film. In doing so, the power hierarchy of the human-animal relationship is reversed.

The resulting effect of the privileging of the dog is the ability to explore and experiment with an answer to Michel de Montaigne’s famed question, ‘when I play with my cat, who knows if I am not a pastime to her more than she is to me?’[7] Montaigne’s question underpins the reality that humans know little about the pet’s view of the world, but One Hundred and One Dalmatians attempts to provide a playful answer in the affirmative, suggesting that the pet is using their owner as much as the owner is using them. The voice-over narration allows an insight into Pongo’s mentality, and he reveals that his human, Roger, is his ‘pet’. This disordering of the human-animal relationship is amusing because it seems outlandish for the pet to have control over the human, but it is only deemed ridiculous because it broadens our limited and anthropocentric perspective of reality to an extent that we have not comprehended before: that animals could be very like us. The film’s unorthodox use of the label ‘pet’ is also intended to trouble the categories of ‘master’ and ‘pet’, eliciting a challenge of what both labels stand for. Respectively, both have derogatory implications of dominance and possession, and subservience and objectification. Pongo’s attempts to resist the label of ‘pet’ and its connotations of inferiority and powerlessness, and Roger’s attempts to assert his authority as the human, are evident in the tussle between Pongo and Roger to be the sole focus of the camera. In this power struggle evocation of tug-of-war, the film implements fast cutting with the shot alternating between Roger and Pongo as they compete for control. With the lead between them symbolising human control and animal restriction, Roger fights to restrain the resisting Pongo as he initiates The Twilight Bark, alerting nearby dogs to the puppies’ kidnapping. Pongo refuses to conform to the expectation of the animal as the passive agent in the pet-owner relationship. So, while the moment does critique the lack of freedom afforded to pets, it compensates by demonstrating animals’ potential to fight for their liberty and power. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ed_Kxyqgp1c&t=2s (The Twilight Bark)

Pongo’s intelligence, agency and resolve is celebrated by a wide, aerial shot of London being consumed by the diegetic barking of dogs during The Twilight Bark, signalling that his act of defiance was successful. This show of domination and rebellion has allowed the pet dogs of London to confront and reject their forced categorisation as ‘an animal (typically one which is domestic or tame) kept for pleasure or companionship’.[10] The dogs refuse to be tamed and reclaim a state of wildness because, in this moment, they are no longer under the control of humans as they conquer the human-centred city with their canine communication. Threatening to ruin the pet dogs’ agency and authority is the diegetic sounds of humans attempting to regain control by shouting commands of ‘shut up’ and ‘quiet’. However, these reprimands and attempts to regain control prove futile against the willpower of the pet dogs, and their barking continues. The power of the pet is, quite literally, announced.

The film also appreciates that being an animal consigned to pet status can be a repressive experience, as epitomised by the carefully crafted vignette of a pet shop window. Lingering on the window, the camera zooms in to a medium shot of the mise-en-scène before panning across the pet shop window. The medium shot is employed to highlight the ‘pet shop’ sign and to showcase a group of dogs to demonstrate the commodification of all dogs bred to be pets. The older dogs’ saturnine expressions suggest a mixture of hopelessness and reluctant acceptance of their situation, with the sense of misery being enhanced by the drab, monotone colours of the mise-en-scène. Homeless and ownerless, the older dogs represent the grim reality for many dogs bred to be pets. Without homes and owners their lives are deemed worthless and their fate becomes euthanasia, rendering their existence futile. The duration of the scene evokes the feeling that the camera is committing voyeurism in observing the pet shop so closely, thereby implicating the audience in this voyeurism to highlight a human tendency to view pets as decoration and entertainment, rather than living beings.

There is a continual sense of voyeurism in the film with windows often being employed in the mise-en-scène to frame, surround and enclose the pet dogs. Not only does this signify pets’ limiting status as a symbol of the home but also illustrates a human inclination to view pets as a decorative object to provide entertainment and aesthetic value. Pongo and Perdy are often situated in the windows of the home, creating the visual effect of their being fenced in by the frame which represents the restrictive and oppressive nature of this patronising attitude to animals. Zoom shots of windows enhance the sense of confinement and entrapment of the window, as the dogs also become increasingly confined by the shot. The claustrophobic effect of the window parallels the enclosed, confined space the houses in the mise-en-scène of the

city create, illustrating the often suffocating lives that pets lead. Condensed, human-centred shots of the city contrast the openness of the wide shots of the countryside which suggest a freer, less constraining life for the animals in this environment, establishing a wildness versus domesticity binary opposition. The dogs become closer to their natural, wild instincts as they return to nature in the countryside, this wildness having been tamed and controlled by domesticity represented by the city. In doing so, the film reminds us that our pets are animals with behavioural needs that need satisfying, including allowing our dogs freedom to explore environments, away from the constraining parameters of the home.

You may have heard that dogs resemble their owners – a thought that Disney takes to an uncanny and amusing extreme by creating clone-like human-pet pairs. Animation allows for the construction of almost identical appearance and temperament in the dogs and humans using colour, costume and choreography of facial expression and movement. The likeness between human and pet denotes a shared identity that signals the pseudo-human role of pets because they blur the boundary between our species; pets are not simply

animals, they are members of our human families, they are our friends, and they are our companions. However, there is an issue with this shared identity. It unveils a narcissistic human proclivity for choosing animals that resemble ourselves in looks and personality, and the human propensity to fashion our pets in our own image.

Figure 20. Stills of the human-pet pairs. [15]

Figure 21. Twinning. [16]

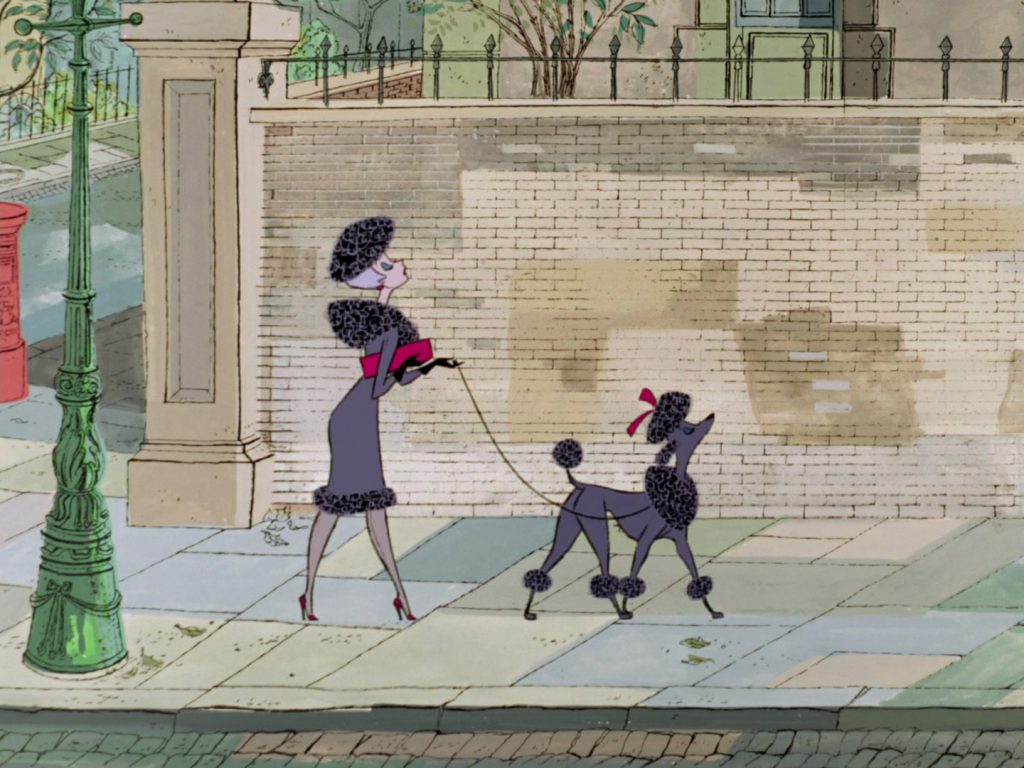

This notion of imposed identity provides an answer to a question posed by Erica Fudge’s Pets: what do humans look for in their pets? [17] One answer offered by the film is that pets are chosen to serve as an extension of the self, or to reflect an improved version of ourselves in the way of a status symbol. For instance, Coco the poodle has been given an identity associated with elitism and

affluence with the name ‘Coco’ most likely being a reference to Coco Chanel, the luxury fashion designer. In accordance with this signifier of high-class, both poodle and owner wear an expression of snobbish indifference, both are dressed stylishly, and they ride in a chauffeur driven car to construct an image of opulence and sophistication. Coco serves as a status symbol to aid in the

affirmation of the woman’s wealth and class. The utilisation of pets in this manner projects an image on to them that is objectifying, diminishing their value as living beings. By exploring the human-pet relationship in terms of human self-validation using an animal, the film exposes and critiques the human desire to exploit animals in the construction of the self.

Our relationship with animals is a complex and constantly evolving affair, none more so than the human-pet relationship. From the good, to the bad and the ugly, the film navigates the problematic relationship humans have constructed with animals by exposing the belittling treatment of dogs as commodities, decorative objects, and self-authenticating symbols. The film implicates the audience and itself, as a visual medium, in the treatment of pets as spectacles for human entertainment, and highlights the sense of observation using a combination of window mise-en-scène, panning and zoom shots. But these pets are not about to be walked all over. Instilled with agency and autonomy, the dogs break free of the medium shot confines of the window into the wide shot openness of the country, shunning human hegemony and the limiting status as a symbol of the home. The film asks us to remember that these animals that form our companions and inhabit our homes are living beings, not ornament, canine ‘mini-me’ or commodity, and they deserve the same respect as any human life. So please do not rush out and buy a Dalmatian after watching the film. How about a stuffed toy instead?

[1] One Hundred and One Dalmatians, dir. by. Wolfgang Reitherman, Clyde Geronimi, Hamilton Luske (Buena Vista Distribution, 1961).

[2] One Hundred and One Dalmatians Movie Poster, digital image of a film poster, Wikipedia, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_Hundred_and_One_Dalmatians> [accessed 3 January 2022].

[3] ITV – Lorraine, screenshot, Daily Mail Online, <https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-8073431/James-Middleton-insists-pet-dogs-saved-life.html> [accessed 19 January 2022].

[4] Mirrorpix, How much is that doggie in the window. Puppies in a pet shop window., digital photograph, Alamy, May 1953, <https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-how-much-is-that-doggie-in-the-window-puppies-in-a-pet-shop-window-20334166.html> [accessed 19 January 2022].

[5] Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books Limited, 2002), p. 82.

[6] One Hundred and One Dalmatians.

[7] Michel de Montaigne, ‘Man is No Better than the Animals’, in An Apology for Raymond Sebond, in The Complete Works: Essays, Travel Journal, Letters, trans. by Donald M. Frame (London: Everyman’s Library, 2003), pp. 401-435 (p. 401).

[8] Digital photograph, Walmart, <https://www.walmart.com/ip/My-Dog-Owns-Me-Men-s-Short-Sleeve-Graphic-T-Shirt/928776647> [accessed 17 January 2022].

[9] One Hundred and One Dalmatians.

[10] ‘Pet, n² and adj.’, sense 1b, Oxford English Dictionary Online, <http://dictionary.oed.com> [accessed 06 Jan. 2022].

[11] One Hundred and One Dalmatians.

[12] One Hundred and One Dalmatians.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Gerrard Gethings, Twinning, digital photograph, Insider, 1 November 2020 <https://www.insider.com/humans-dogs-identical-2018-9> [accessed 19 January 2022].

[17] Erica Fudge, Pets (London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2014).

[18] CNN Money, digital image, Their Turn, 15 August 2014 <https://theirturn.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/140813093015-big-dog-hk-620xa.jpg> [accessed 17 January 2022].

[19] One Hundred and One Dalmatians.

Bibliography

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books Limited, 2002)

CNN Money, digital image, Their Turn, 15 August 2014 <https://theirturn.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/140813093015-big-dog-hk-620xa.jpg> [accessed 17 January 2022]

de Montaigne, Michel, ‘Man is No Better than the Animals’, in An Apology for Raymond Sebond, in The Complete Works: Essays, Travel Journal, Letters, trans. by Donald M. Frame (London: Everyman’s Library, 2003), pp. 401-435

Digital photograph, Walmart, <https://www.walmart.com/ip/My-Dog-Owns-Me-Men-s-Short-Sleeve-Graphic-T-Shirt/928776647> [accessed 17 January 2022].

[17] Fudge, Erica, Pets (London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2014)

Gethings, Gerrard, Twinning, digital photograph, Insider, 1 November 2020 <https://www.insider.com/humans-dogs-identical-2018-9> [accessed 19 January 2022]

ITV – Lorraine, screenshot, Daily Mail Online, <https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-8073431/James-Middleton-insists-pet-dogs-saved-life.html> [accessed 19 January 2022]

Mirrorpix, How much is that doggie in the window. Puppies in a pet shop window., digital photograph, Alamy, May 1953, <https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-how-much-is-that-doggie-in-the-window-puppies-in-a-pet-shop-window-20334166.html> [accessed 19 January 2022]

One Hundred and One Dalmatians, dir. by. Wolfgang Reitherman, Clyde Geronimi, Hamilton Luske (Buena Vista Distribution, 1961)

One Hundred and One Dalmatians Movie Poster, digital image of a film poster, Wikipedia, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_Hundred_and_One_Dalmatians> [accessed 3 January 2022]

Further Reading

Baker, Timothy C., ‘”Oh, my dog owns me”: Interspecies Companionship in Dodie Smith and Diana Wynne Jones’, The Lion and the Unicorn, 41.3 (2017), 344-360 <http://doi.org/10.1353/uni.2017.0031>

Filipi, David, ‘101 Dalmatians’, Film Comment, 51.3 (2015), 75

Fudge, Erica, Pets (London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2014)

Navarro, Mireya, ‘After Movies, Unwanted Dalmatians’, New York Times, 14 September 1997 <https://www.nytimes.com/1997/09/14/us/after-movies-unwanted-dalmatians.html> [accessed 10 January 2022]

Podberscek, Anthony L, Elizabeth S Paul, and James A Serpell, Companion Animals and Us: Exploring the Relationships between People and Pets (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005)

Redmalm, David, ‘To Make Pets Live, and to Let Them Die: The Biopolitics of Pet Keeping’, in Death Matters: Cultural Sociology of Mortal Life, ed. by Tora Holmberg, Annika Jonsson, Fredrik Palm (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), pp. 241-63