It’s 1992, and Christopher McCandless, reborn as Alexander Supertramp, embarks on a ‘rite of passage for a young man in search of meaning,’[1] escaping from the human world and into the Alaskan wilderness. A ‘vagabond loner’[2] who donates his college fund to Oxfam and abandons his worldly goods by the side of the road, Alex forges relationships with the people he meets along the way, as well as to the wild landscape that he inhabits. Motivated by his disconnection to the human world he lives in his declaration that “you’re wrong if you think the joy of life comes from human relationships” is powerful, forcing the audience to question his beliefs, while also revaluating their own. Retreating from the human world allows him entry to the secluded animal one, vowing to exist beside theses creature in their own harsh sphere. His adventure however is unsuccessful – he survived 114 days (according to journal entries) living in his magic bus[3] before he died of starvation, writing in his journal that he had “literally become trapped in the wild.”[4]

Adapted from the 1996 biography by Jon Krakauer, Into the Wild hybridises genres – it is an adventure film, a drama, yet behind the façade of Eddie Vedder’s soundtrack that ‘evokes the eerie beauty of untouched land,’[5] and impressive cinematography, is the real life story of Christopher McCandless. The film is not a documentary, yet it does intend to reveal McCandless’s last months in the wild, which he himself documented in his diary, along with a series of self -portraits found undeveloped on his camera.[6] Brown and Vidal suppose that ‘documentaries transform pieces of a life and partial accounts into a seamless chronicle of death foretold’[7] and this seems to be what Penn’s film attempts to do, despite it not firmly being situated as a documentary. On the subject of the adventure film, Tasker writes that ‘displays of the male body and of the hero’s physical prowess are traditional in all kinds of adventure films’[8] and it cannot be disputed that the camera has a ‘clothes-off relationship with him, repeatedly caressing him in slo-mo.’[9] Perhaps then, this is why Penn chooses to present the opposite, the male form when the adventure is failing, and when the adventure is unsuccessful. McCandless charts his journey through the many holes he has to create in his belt – a termination from conventional adventure genres and the show of physical prowess in place of a representation of it having all gone wrong.

Picture: Emile Hirsch as Christopher McCandless

Animals, as characters, do not feature greatly in the narrative story of Into the Wild, nor are they anthropomorphised, given the power of speech or named. Peter Bradshaw writes that ‘nature in the raw is rarely shown in the movies to exist on its own account without an overt dramatic function […] but this picture lets nature simply be’[10] and this can arguably be where animals fit into the greater story. They appear to reveal intriguing aspects of human life, and what it means to detach oneself from the human world and retreat into a world adhering to the way of animals. Animals are used to represent a different way of life, and the binary between culture and wilderness is prevalent here in its strongest form.

McCandless’s desire to ‘experience the raw throb of life without a safety net’[11] presents the wild as a total binary world to the human one – from the very beginning long establishing shots try to show just how epic the wild is, contrasted with the small spaces of civilisation. The non-linear narrative takes advantage of a lack of dialogue at the start of the film as McCandless set off on his journey. Coupled with long, sometimes almost aerial shots, the camera pans over the vast expanse as a flock of birds take flight, flying into the great unknown and escaping the constraints of the human world. They seem to symbolise Alex’s journey as he too is escaping from the human world, going northwards into the unknown. This symbolism is further accentuated through clever editing as voiceover and camera merge to represent animals as a symbol of freedom. McCandless describes himself as “an aesthetic voyager” entering “ultimate freedom” as the camera tracks a herd of moose running freely through the wilderness. He is being seduced into this world and it is by the power of animals and all that they come to stand for that this is possible.

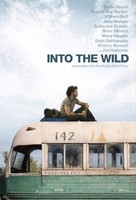

Picture: Into the Wild

McCandless’s desire to “live off the land” in a coexistence with these animals is articulated through his conversation with hippies Jan and Rainey who proclaim that “you can’t depend entirely on leaves and berries.” His exclamation that “I don’t know if I want to depend on more than that” further expresses his desire to rid himself of all material goods, while associating him firmly with the animal world. The significance of this proclamation is that it is entirely what animals do – he wants to retreat back to the furthest state of being and his search for escapism leads him to this animal world. Interestingly, Jan and Rainey also refer to his journey on foot, as opposed to by vehicle, as an attempt to “hoof it” – a very animalistic image

This desire is later made problematic as he is forced to shoot a moose – various slow motion shots reveal him shoot and slit its throat before chopping it up and smoking it. Soon after, he comes to the realisation that the corpse is rotten and riddled with maggots, and this is significant in further exploring the animal world. He writes that “I wish I never shot the moose” before we see wolves eating the now unwanted corpse. This marks a point in the story where he seems to lose hope – he writes it is the “greatest tragedy of my life” before his voiceover tells that he is in “a forest not bound to be kind to man.” Here the binaries between the human and animal worlds are most prevalent. It is, almost literally, a dog eat dog world in the wild, and this is something that Alex struggles to comprehend. In order for nature to exist the way it has done, these animals must exist and benefit from each other in a way other than how humans do. It represents the unpredictably of the animal world, and how difficult, impossible almost, it is to cross the boundary into it. This seems to be Alex’s hamartia – earlier on while hunting we see him taking aim at a deer, yet when her faun appears through the trees he puts down his gun, unable to kill her. Alex cannot act like an animal would in the animal world, while also being unable to exist in the ‘human’, cultural world.

Picture: Self-portrait found on McCandless’s camera at his ‘magic bus’

Interestingly, the only domestic animal that features in the film is a guard dog which sniffs Alex out as he attempts to hitchhike on a train. The dog here is represented as dangerous, violent, and the dark and confining mise en scene seem to mirror the confinement and restrictiveness McCandless sought escape from. As an animal existing in a human world, for a human purpose, the dog is fully under human control and has been taught and trained to act a certain way – much like Alex was felt he was. This is a huge contrast to animals that Alex witnesses in the wild. It could be argued that even animals become corrupted once they leave their natural environment, and this idea of corruption is presented as a deer drinks from the stream, and nature is at peace, before a plane shoots through the sky overhead, sending birds flying. It implies that man, and modernity, has invaded nature and is totally in control.

Bradshaw argues that the film poses questions ‘about what it is to be human, and what happens when we admire nature more than humanity: does it make us less than human, or do we fulfil and even transcend our humanity?’[12] Christopher McCandless tried to transcend his humanity, but died while doing so. Thus, the film asks can we ever go back to such a raw state of nature and live as animals do? Or are the boundaries not even boundaries but fixed, intrinsic values of humanity and animality that we cannot rid ourselves of? Maybe humans should leave the animals to their wild, ungoverned world and we should stick to our own. Into the Wild uses animals, and all that they represent, to explore the binary between culture and nature, and reinforces the statement that ‘man is an interloper in an otherwise balanced wilderness.’[13]

A true story of a man retreating into the animal world draws comparisons to Werner Herzog’s documentary Grizzly Man (2005,) yet due to genre they tell true life very differently. Grizzly Man uses original footage shot by Timothy Treadwell, combined with interviews with those who knew or encountered him, while Penn’s adaption ‘does not insist on a dramatic storyline of depression or anger leading to McCandless’s death.’[14] It draws the audience in and allows them to feel as if they are experiencing McCandless’s journey with him, with no biases or attempts to judge or critique him. As men retreating from the human world and into the animal one however, both films arguably fulfil McCandless’s statement that “you don’t need human relationships to be happy. God has placed it all around us,” and it is through the use and symbolisation of animals that this is achieved.

Bibliography:

Bradshaw, Peter, ‘Into the Wild’, The Guardian (2007), <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2007/nov/09/seanpenn.drama>

Brown, Tom and Vidal, Belén, ed., The Biopic in Contemporary Film Culture, (London: Routledge, 2013)

‘Christopher McCandless’ (2011) <https://www.christophermccandless.info/bio.html>

Jolin, Dan, ‘Into the Wild’ Empire Online <https://www.empireonline.com/reviews/reviewcomplete.asp?DVDID=117800&page=3>

Jonson, Eric, ‘Into the Wild’ Chris McCandless’ Sister Says He Was Determined to Cut Ties with Parents’, ABC News (2014) <https://abcnews.go.com/Entertainment/wild-chris-mccandless-sisters-journey-escape-traumatic-childhood/story?id=26743275>

Krakauer, Jon, ‘How Chris McCandless Died’, The New Yorker (2013), <https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/how-chris-mccandless-died>

Marchese, David, ‘Eddie Vedder, Music for the Motion Picture Into the Wild’, Spin (2007) < https://www.spin.com/reviews/eddie-vedder-music-motion-picture-wild-jmonkeywrench/>

Roberts, David, ‘Jon Krakauer and Sean Penn: Back Into the Wild’, National Geographic: Adventure (2007) <https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/news/into-the-wild.html> [accessed 5 January 2015].

Tasker, Yvonne, ed., Action and Adventure Cinema, (London: Routledge, 2004)

Further Reading:

Film reviews:

IMDB page: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0758758/

Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g7ArZ7VD-QQ

Christopher McCandless website: https://www.christophermccandless.info/bio.html

Article by Jon Krakauer speculating how Christopher McCandless died: https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/how-chris-mccandless-died

Article about Christopher McCandless and the film: https://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-adventure/media/books/Chris-McCandless-The-Wild-Truth-Book.html

[1] David Roberts, ‘John Krakauer and Sean Penn: Back Into the Wild’, National Geographic: Adventure (2007) <https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/news/into-the-wild.html> [accessed 5 January 2015].

[2] Ibid.

[3] Eric Jonson, ‘Into the Wild’ Chris McCandless’ Sister Says He Was Determined to Cut Ties with Parents’, ABC News (2014) <https://abcnews.go.com/Entertainment/wild-chris-mccandless-sisters-journey-escape-traumatic-childhood/story?id=26743275> [accessed 5 January 2015].

[4] Ibid.

[5] David Marchese, ‘Eddie Vedder, Music for the Motion Picture Into the Wild’, Spin (2007) < https://www.spin.com/reviews/eddie-vedder-music-motion-picture-wild-jmonkeywrench/> [accesses January 5 2015].

[6] ‘Christopher McCandless’, (2011) <https://www.christophermccandless.info/bio.html> [accessed 6 January 2015]

[7] The Biopic in Contemporary Film Culture, ed. by Tom Brown and Belén Vidal, (London: Routledge, 2013) p. 16.

[8] Action and Adventure Cinema, ed. by Yvonne Tasker (London: Routledge, 2004)p. 75.

[9] https://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/review/4100

[10] Peter Bradshaw, ‘Into the Wild’, The Guardian (2007), <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2007/nov/09/seanpenn.drama> [accessed January 4 2014].

[11] Jon Krakauer, ‘How Chris McCandless Died’, The New Yorker (2013), <https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/how-chris-mccandless-died> [accessed January 5 2014].

[12] Peter Bradshaw, ‘Into the Wild’, The Guardian (2007), <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2007/nov/09/seanpenn.drama> [accessed January 4 2014].[13] Dan Jolin, ‘Into the Wild’ Empire Online <https://www.empireonline.com/reviews/reviewcomplete.asp?DVDID=117800&page=3> [accessed January 7 2015]

[14] Ibid.