There is a surprising lack of non-human animal representation in Studio Ghibli’s 2004 film Howl’s Moving Castle, despite an overarching theme which frequently pits an idyllic pastoral version of Japan against a threateningly industrial one. The major depiction of human-animal relations is that of secondary protagonist Howl as he gradually transforms into a bird-like creature in order to interfere with an ongoing war. Howl’s transformation is consistently warned against by the fire-demon Calcifer, who cautions that “soon you won’t be able to turn back into a human” – yet the narrative suggests that the only way to resolve the industrial problems faced by society is through a return to the natural world. [1]

In what is ambiguously a dream-sequence, the film’s protagonist Sophie finds Howl in a state which is initially conveyed to be abjectly horrific – his usually conventionally-attractive human face replaced with that of a beast-like creature with fangs in an extreme close up.

The cave in which she finds him is dark, yet also filled with treasures; recalling both Howl’s vanity as well as the tendency of some corvids to hoard shiny objects. By reflecting human behaviour in avian ethology, Miyazaki suggests that in some ways this human/bird hybrid is in fact Howl’s truest form, laying bare his animalistic qualities as visually unsettling in order to match reservations regarding his character.

Whilst large black birds such as crows and ravens are often considered to be signifiers of malintent in Western societies, in Japanese Shinto Mythology the Yatagarasu or “eight-span crow” is a symbol of divine intervention. [2]

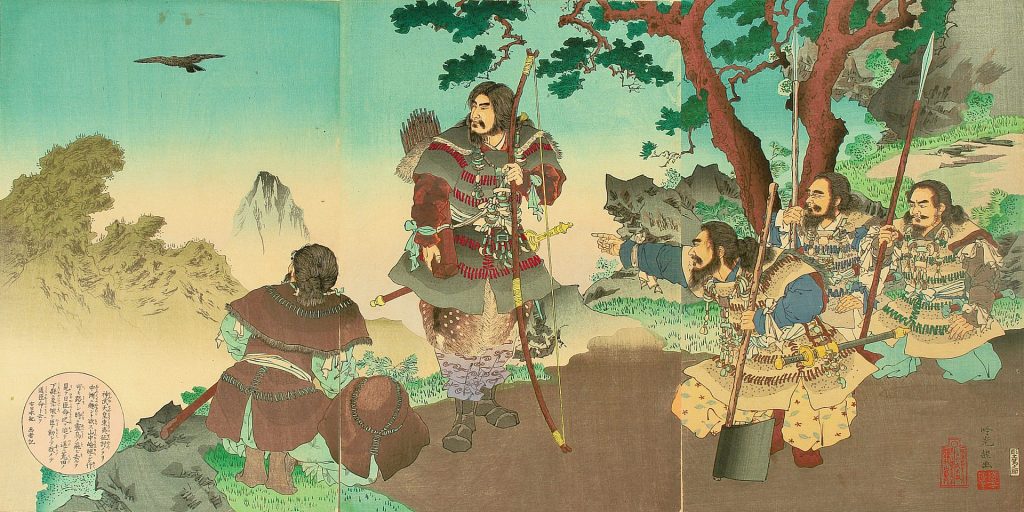

Woodblock print depicting legendary first emperor Jimmu, who saw a sacred bird flying away while he was in the expedition of the eastern section of Japan. [3]

The depiction of Howl as a bird-like beast therefore signifies his adoption of an animalistic nature in order to combat the threat of industrial machinery which is utilised by the warring factions. By emphasising a return to a pastoral ideal, the film demonstrates that both Howl and society at large must tackle their inner ugliness in order to co-exist with the imperfect beauty of the natural world.

Ultimately, Howl’s redemptive arc sees him shed his undesirable qualities of selfishness and vanity as he works to protect Sophie and the growing number of inhabitants of his moving castle against the effects of the ongoing violence. Despite the precarious nature of his repeated transformations into a human/non-human animal hybrid, Howl ultimately retains the most obvious marker of his non-animality in his human face, suggesting that a mutual relationship between humans and non-human animals is necessary in order for society to progress.

In a film which continually demonstrates the importance of not taking others at face value, Howl’s hybridity can be read as an argument for the virtues of non-human animals. In order to move away from the nightmarish industrial landscape of the war, humans must be prepared to accept the potential benefits of their animalistic qualities and consider a more peaceful relationship with the natural world.

Footnotes

[1] Hayao Miyazaki, Howl’s Moving Castle (ハウルの動く城) (Tokyo, Japan: Studio Ghibli, 2004),41:55.

[2] Hiroko Yasuda, “World Heritage and Cultural Tourism in Japan”, International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4.4 (2010), 368 <https://doi.org/10.1108/17506181011081532>.

[3] Wikipedia, Emperor Jinmu – Stories From “Nihon Shoki” (Chronicles of Japan), 1891 <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tenn%C5%8D_Jimmu.jpg> [Accessed 25 April 2020].

Bibliography

Miyazaki, Hayao, Howl’s Moving Castle (ハウルの動く城) (Tokyo, Japan: Studio Ghibli, 2004)

Wikipedia, Emperor Jinmu – Stories From “Nihon Shoki” (Chronicles of Japan), 1891

<https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tenn%C5%8D_Jimmu.jpg> [Accessed 25 April 2020]

Yasuda, Hiroko, “World Heritage and Cultural Tourism in Japan”, International Journal of Culture,

Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4 (2010), 368 <https://doi.org/10.1108/17506181011081532>