Hoodwinked! [2005]

A retelling of the folktake Little Red Riding Hood as a police procedural, using backstories to show multiple characters’ points of view.[1]

Hoodwinked! follows the classic who dunnit trope, deconstructing the fable of Little Red Riding Hood with a modern twist to narrate the mystery of the Goody bandit. It entertains basic animal stereotypes to translate the moral of never judging a book by its cover, most notable in the characterisation of Wolf. W. Wolf who goes beyond the looks of the animal. The Rashomon approach to the narrative enforces this by proving ‘seeing is not always seeing clearly’ representing how stereotyping corrupts reality and perceptions. Cory Edward’s inclusion of the classic fairy tale reinforces negative stereotypes surrounding wolves’ resulting in the hoodwinking of all characters proving how damaging and indoctrinating stereotyping is to animal welfare and cohabitation in human-animal relations.

Hoodwinked! portrays wolves to symbolise the concepts of subjectivity and unreliability that constitute stereotyping, exploring its effect on animal agency and protection in human-animal relations. Hoodwinked! uses the animality of the wolf, and its history of negative cultural inferences, to represent the shallowness of stereotyping and how its perception is often skin deep. Negative associations enforced in the folklore tale and the Grimm Brothers mean the cultural production of the wolf is the perfect ground for exploring and critiquing stereotyping.

Red riding hood, you probably already know the story, but there’s more to every tale than meets the eye, it’s just like they always say, you can’t judge a book by its cover. If you want to know the truth, you’ve got to flip through the pages.[2]

-Narrator

Hoodwinked! opening scene references the Grimm Brothers’ to establish the negative cultural inferences of wolves, fortified through the sinister dynamic depiction between Little Red Riding Hood and the Big Bad Wolf. Their archetypal names are indicative of their stereotypes, ‘little’ insinuating vulnerable and ‘bad’ implying evil, although Hoodwinked! reinvents these to represent its retelling of the tale and its stereotypes.

A vignette bordering the frame signifies all-consuming darkness, eliciting a sense of impending doom and creating an ominous atmosphere to compliment the human-animal relation depicted in the aged image that emerges from the darkness. Its black-and-white tone emphasises the all-black-and-white judgment associated with stereotyping. The woods as a setting are a dark enough environment that you ‘can’t see the wood for the trees’, alluding to the film’s moral of being so involved in the details of something that you can’t see the whole picture. A flickering effect reminiscent of an old tape overlays the illustration, a reminder of how innately cultural this stereotype is in society.

Little Red Riding Hood cowers beneath the Big Bad Wolf baring his teeth, indicative of hostility and intention to attack. The distinctions in physical positioning and size scaling translate the power dynamic, establishing who is prey and predator. The vulnerability of Little Red Riding Hood in her childlike innocence, small stature, arms held up in defence, and horror-stricken expression elicits sympathy. Posing no threat, she is defenceless, depicting her as prey. The savage depiction of the Big Bad Wolf through the demonic blackening of his eyes references the hollowness of his soul; darkness consumes him, portraying him as an immoral predator. Depicting this before an introduction to the character of Wolf. W. Wolf predominantly attaches negative expectations to him. Inferring this dynamic villainises him before a chance to defend himself, making the stereotype [a product of human fiction] harder to escape. The scene’s cinematography reinforces this predator-prey relation by re-enacting the dynamic. Zooming in with a swooping angle mimics the act of chasing, and the camera weaving between the trees imitates escaping, building tension similar to the flight/survival instinct until the fast-paced focus settles on a cabin in the woods.

<Fig 3. Crime scene depiction>

Mise-en-scene isolates Wolf. W. Wolf as he inhabits a red chair separate from the characters inhabiting the sofa. The compartmentalisation of the wolf accentuates him as the only animal in a human line-up, representing the alienation stereotyping induces; segregation prevents habituation and familiarisation, increasing hostility and encouraging prejudice. An increase in prejudice increases avoidant behaviour, affecting animal welfare and preventing advocacy and protection acts. Red inferences the wolf, representing the aggressive belief [‘seeing red’] people have of stereotyped individuals. It implies danger, and association with the wolf perceives him as a threat. Red also signifies a target, the bull’s eye, alluding to the wolf as a target of profiling observed through the hypocrisy of Red Puckett adorning red but receiving softer treatment. He is hunted within the human-animal relation.

Once hunted, he becomes trapped by the negative expectations of wolves. As a result, he is the only character muzzled and leashed, an allusion to a violent dog and its handler. Muzzles are associated with dog breeds, such as Pitbull’s, prohibited because of their history as fighting dogs. The generalisation of the Canis Lupus species indicates law enforcement based their actions on negatively generalised prejudices, reinforcing that the muzzle is a product of stereotyping. It is a retaliation of police brutality justified through the profiling of the wolf based on cultural extrapolations of violence, subtly commentating on the corruptness of the justice system. Muzzles entrap and restrict, removing animal agency and reasserting the ideological power dynamic that animals are inferior to humans. Therefore, the practical reality of this relation is objectification in taming and controlling.

The 23 Lakers jersey that Wolf. W. Wolf adorns [Fig 3] references the comedic character Fletcher, an undercover reporter in the franchise Fletch [1985]. This allusion pictures wolves as playful, contrasting the predatory depiction referenced in the opening scene. Wolf. W. Wolf is an intrepid reporter, a role that is often stereotypical of being biased and unreliable. When undercover, he disguises himself for anonymity which infers duplicitous. Reminiscent of the stereotypical idiom, he is a wolf in sheep’s clothing or in the context of the fable, Granny’s clothing. Consequently, this exposes him as a habitual liar who conceals his identity and intentions to gain information, an association that tarnishes his credibility when testifying, ‘Why should we trust someone who wears disguises for a living?’[3] However, as a character constantly changing appearances, his duality furthers the ambiguity of his depiction, disproving his general stereotype. A tendency to shapeshift proves stereotypes are not rigid constructs applicable to all. It is impossible to make reliable judgments on external appearances alone. His ambiguity means his actions and dialogue are open to interpretation, making him vulnerable to the negative assumptions of his stereotype. ‘Wow, something smells good’[4] insinuates he thinks Red Puckett smells good enough to eat, dismissing the basket of baked goods she’s holding and exposing the narrow-minded, blinkered vision of stereotyping. Its subjectivity leads to selective interpretation and recollection, demonstrated in unreliable testimonies. [Fig 4]

The plot consists of non-linear narratives, broken down into four separate testimonials in the form of flashbacks, detailing each character’s journey to the present situation, their paths intercepting as metatextual wires cross. Each flashback has a major misinterpretation which highlights the narrative structure’s concept of an unreliable narrator, its storytelling sets the scene for the movie’s consensus about the misinterpretation of stereotyping.

Alluding to Rashomon (1950), the Rashomon effect allows for a multidimensional sense of the wolf. Constructions of his perceptions, through subjective flashbacks, replicate its structure alluding to the process/effect of stereotyping. Effectively, a Rashomon effect of the wolf. The sequence of events through multiple lenses highlights how stereotyping affects the retelling of reactions/interactions between characters. Red Puckett’s recollection of her encounter with the Wolf. W. Wolf ironically victimises herself by not detailing her attack on him to seem more innocent while dramatically exaggerating his ferocity. His roar is scarier when compared to the painful roar in his recollection, later revealed as a result of trapping his tail in the camera, demonstrating the unreliability of witness testimonies and how disjointed messages corrupted conclusions.

Visual signifiers further enhance this through lighting. In Red Puckett’s perspective, Wolf. W. Wolf is standing in the dark, instantly associated with a stalker while she is in the light to illuminate her innocence. From his perspective, they are both in the light depicting his unbiased perception of their innocence and showing he is purer intentioned. A reoccurring theme through all flashbacks, lighting varies in perspectives signifying how they perceived things in a different light. Each testimony lightens as they get closer to the truth and reveal the culprit, symbolic of finally seeing the light.

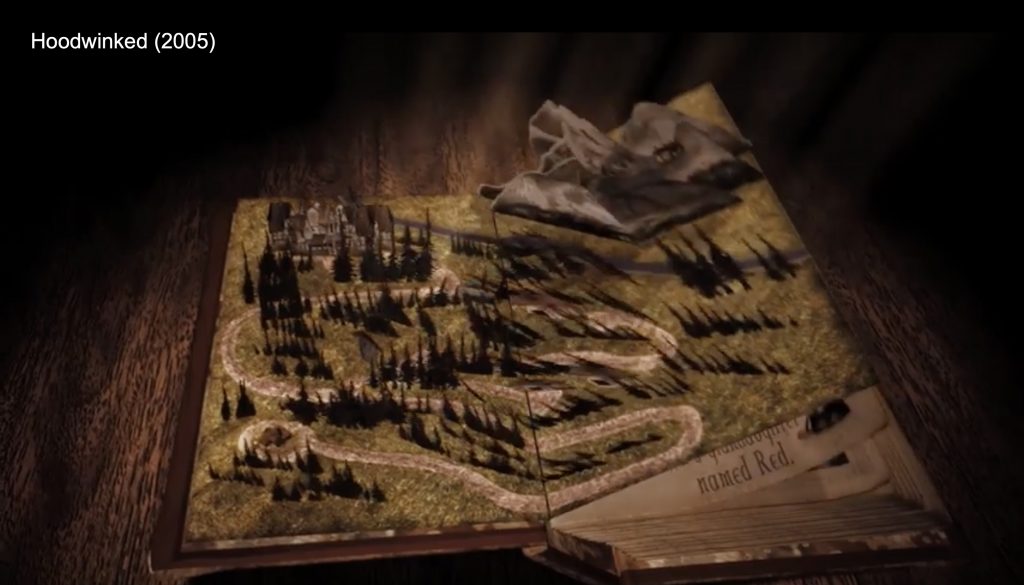

The storybook transition, a sequence of camera work that mimics the flicking and weaving through the pages of a storybook, marks the switching of narratives between characters and their testimonies. Its 3D storytelling technique sets the scene as a classic folklore tale, highlighting the metatextual aspect of its narrative structure while immersing and informing the audience that the following events are fiction, detailed through testimonies, as a result of unreliable witness accounts. When the storybook flips back to begin each character’s story, snippets of text from the Brothers Grimm version of the original fairy tale are observable, a reminder of the classic stereotypes.

<Fig 5. Storybook Transition>

Hoodwinked! is not exclusively a retelling of a fairy tale but a retelling of classic negative stereotypes. It deconstructs the predatorial prejudices of wolves and purifies them, presenting them in a new light. One way this process is documented is through the lightening of the flashback narratives as underlying prejudices, exposed through the who dunnit trope, towards the wolf slowly change. The Rashomon structure symbolises this exploration for truth. Utilising its approach to the stereotype of the wolf unravels its subjective perceptions, revealing an accurate depiction. Its narrative equips a cyclical/reverse structure where we begin at the end, producing the effect of coming full circle and tying up loose ends, foreshadowing the inevitability of reforming negative stereotypes.

Cinematic techniques in Hoodwinked! interlink in exposing the flaw in human-animal relations, the intrinsic desire to stereotype species/breeds to the degree of endangerment and extinction. The police procedural and its process of profiling the wolf is a perfect allusion to human’s treatment of negatively stereotyped animals and how it affects their welfare. Representations of wolves in human-animal relations are applicable to society and the dangers of stereotyping animals. Danger labelling certain animals influences their reputation, perceiving them as more threatening and increasing the likelihood of defensive violence. Active harm behaviours such as targeted hunting and muzzling prevent facilitation in animal welfare and result in animal endangerment and extinction.

Hoodwinked! portrays the cohabitation and collaboration of human-animal relations although the underlying practical reality remains, animals are inferior, degraded through stereotypes and controlled through profiling by authoritative powers. It highlights how effective cohabitation is not possible unless we retell these stereotypes otherwise animals will always remain inferior. The justice system [an institute of authoritative power like humans] fails to save the woods and its inhabitants, it is the cohabitation of animals that prevails. Contrary to the stereotype of the Big Bad wolf and its dynamic with Little Red Riding Hood, humans are the big and bad predators, the real culprits endangering animals and their habitat.

Further Reading

- Sevillano, V. & Fiske, S.T. (2019). Stereotypes, emotions, and behaviors associated with animals: A causal test of the stereotype content model and BIAS map. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 22(6), 879–900.

< https://faunalytics.org/how-stereotyping-affects-our-attitudes-and-behavior-toward-animals/>

< https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/136843021…>

- “Rothkäppchen,” Kinder-und Hausmärchen, 1st ed. (Berlin: Realschulbuchhandlung, 1812), v. 1, no. 26, pp. 113-18. Translated by D. L. Ashliman.

- Andrew Lang, The Blue Fairy Book, 5th edition (London: Longmans, Green, and Company, 1891), pp. 51-53. Lang’s source: Charles Perrault, Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités: Contes de ma mère l’Ove (Paris, 1697).

- Grimm Brothers, “Little Red-Cap (Little Red Riding Hood),” Grimm’s Fairy Tales, Lit2Go Edition, (1905), accessed January 20, 2023. <https://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/175/grimms-fairy-tales/3083/little-red-cap-little-red-riding-hood/.>

Bibliography

- Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Rashomon and Other Stories, (Liveright: 1999)

- TV tropes (no date) TV Tropes. Available at: https://tvtropes.org/ (Accessed: January 20, 2023)

- Edwardes, M., Taylor, E., trans. (1905). Grimm’s Fairy Tales. New York: Maynard, Merrill, & Co

Filmography

- Edwards, Cory, dir., Hoodwinked! (Kanbar Entertainment, Blue Yonder Films:2005)

- Kurosawa, Akira, dir., Rashomon (Daiei Film:1950)

- Ritchie, Michael, dir., Fletch (Universal Pictures: 1985)

Figures

- AnimatedMoviesCentral, Hoodwinked! – Trailer (2005), online video recording, YouTube, 19 December 2012, <https://youtu.be/RGV-cTSr6zg> [accessed 15 January 2023]

- LookMovie,< https://lookmovie2.to/movies/view/0443536-hoodwinked-2005 > [accessed 10 January 2023]

- LookMovie,< https://lookmovie2.to/movies/view/0443536-hoodwinked-2005 > [accessed 11 January 2023]

- dimitreze, Hoodwinked! (2005) – scene comparisons, online video recording, YouTube, 29 June 2018,<https://youtu.be/sXBtMe2GEZo > [accessed 12 January 2023]

- LookMovie,< https://lookmovie2.to/movies/view/0443536-hoodwinked-2005 > [accessed 12 January 2023]

References

[1]Hoodwinked!. (2023, January 11). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hoodwinked!

[2]Edwards, Cory, dir., Hoodwinked! (Kanbar Entertainment, Blue Yonder Films:2005)

[3]Edwards, Cory, dir., Hoodwinked! (Kanbar Entertainment, Blue Yonder Films:2005)

[4]Edwards, Cory, dir., Hoodwinked! (Kanbar Entertainment, Blue Yonder Films:2005)