Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban: Official Trailer [i]

In 2004, Warner Bros. unveiled the third Harry Potter instalment, blessing the film franchise with the innovative, ingenious, and cinematically distinctive director Alfonso Cuarón. Back at Hogwarts for their third year, Harry Potter (Daniel Radcliffe) and his friends Hermione Granger (Emma Watson) and Ron Weasley (Rupert Grint), are instantly faced with their next adventure. During this, the three young wizards encounter a number of creatures: not least those of Hermione and Ron’s troublesome pets, Crookshanks and Scabbers; but also a rouge werewolf and a sinister black dog: the respective, metamorphosed counterparts of Professor Lupin (David Thewlis) and Sirius Black (Gary Oldman); and most notably, the magnificent yet misconstrued hippogriff Buckbeak. The narrative opens with the news that Black, a notorious serial killer, has escaped from Azkaban Prison, and is reportedly hell-bent upon taking Harry as his next victim. Yet embarking upon turbulent teenage years, Harry’s quest for the truth in his parents’ murder leads him to discover that Black is in fact his innocent, misunderstood godfather. Throughout, the young wizard develops a kinship with Buckbeak, this trust establishing the means which ultimately rescues Sirius from his doomed fate. Thus whether mortal animal or mythical beast, the presence of animals in the film, and their relationship with the characters onscreen, plays a fundamental role in both the unveiling of the narrative’s pivotal secrets, and in its more profound political commentary.

With its often dark, fast-paced narrative and pervading sense of mystery, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban evidently adheres to the action and adventure genres. Yet, set in the magical world of Hogwarts, each of these features in this instance, falls under the broader umbrella of fantasy. Through its incorporation of elements of a myriad of genres, fantasy is rendered as both unrestricted and broad in definition. Jack Zipes comments upon this vast nature, stating that fantasy is generally expressed, ‘In most European languages, [to mean]…imagination.’[ii] With consideration for this, the genre therefore stems from the mind’s eye, with its autonomy to formulate a fabrication of what is situated beyond the real. J.K. Rowling’s fictional wizarding world sits comfortably within this, its many gateways to contemporary society, in which humans are called muggles, fulfilling it with a sense of plausibility, and providing its audience with a realistic paradigm through which to reflect upon their own world.

Through this realm of fantasy, the film connects with its predominantly young audience, simultaneously addressing common generic notions of the family film, such as the tumult of adolescence. Cara Lane likewise comments upon this, stating that: ‘Harry…(and the viewers) must…lose their innocence,…and come of age. Cuarón’s bridging of the muggle and magical worlds helps to universalize these lessons, allowing his viewers to apply them to their own.’[iii] Cuarón thus takes advantage of the fantastical elements of Harry Potter, utilising it as a medium through which to connect with the audience upon the real-world issue of ‘a child…[finding] his identity as a teenager’[iv].

This crossover between the real and imaginary, allows the film to approach similarly insightful issues regarding its representations of animals. The fantasy world of Harry Potter permits the presence of mythical creatures, such as Buckbeak the hippogriff. Portrayals of the legendary beauty and other-worldly power of this creature, expose the audience to supremacy within the animal kingdom, thus leading them to question the typical ranking of humans above animals in the real world. The fantasy genre therefore provides a means through which a number of different binaries can be crossed: not least that between real and imagined, but also that between humans and animals.

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban: Scene in which Harry Potter meets Buckbeak [v]

At the opening of the scene where Harry and Buckbeak first meet, a wide, long shot is used, in which the students take one side, and Buckbeak the other. Consequently, a divide is visually established between the two species, immediately highlighting the wizard-animal binary, while simultaneously establishing the audience’s objective position as onlooker. Here the young witches and wizards are pictured in dishevelled school uniform, as opposed to their conventional dress robes. This aligns them with typical teenagers, thus encouraging the audience’s ability to relate to the situation onscreen. At this moment, the camera moves gradually closer, as Harry tentatively crosses the divide, (Figure 1) finally resting in an intimate close-up, in which he is framed touching the hippogriff’s beak. (Figure 2) These progressive movements highlight the formidable nature of the beast, through their embodiment of the cautiousness required in which to approach it. Coupled with the prerequisite bow: a demonstration of respect to Buckbeak, through which Harry is able to acquire his trust, this enhances the presence of the mythical creature as a figure both of majesty, and of superiority to humanity. Through Buckbeak, Cuarón therefore demonstrates the power of the animal kingdom, the audience’s feelings of awe and trepidation towards the creature, instilling within them a renewed idea of the status of animals. Thus they are alerted to the need to advocate for improved respect for, and treatment of like-creatures in society as a whole.

Figure 1: Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban – Harry tentatively approaches Buckbeak

Figure 2: Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban – Harry touches Buckbeak

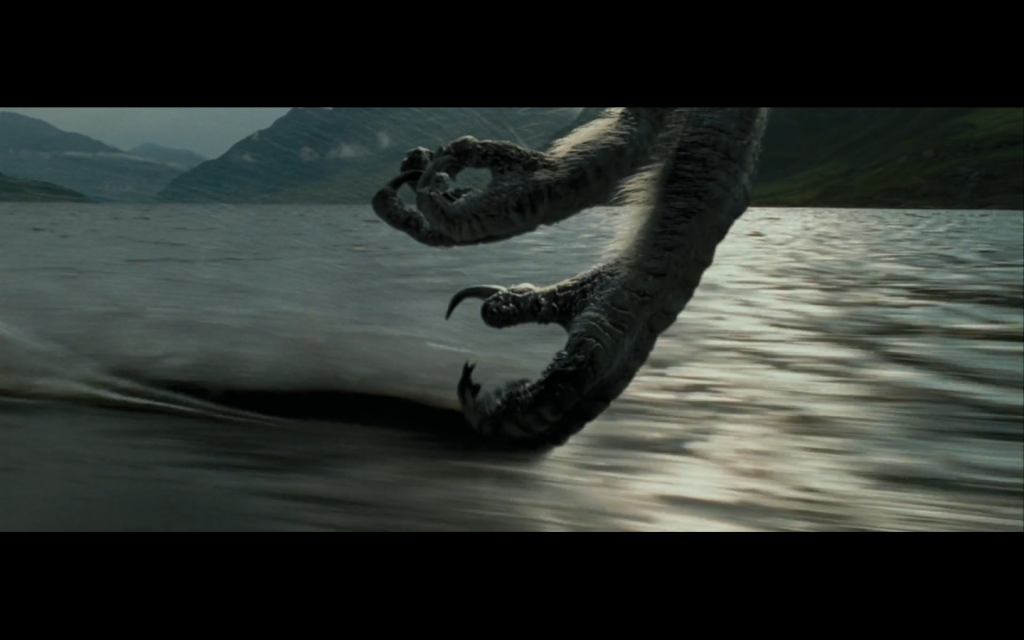

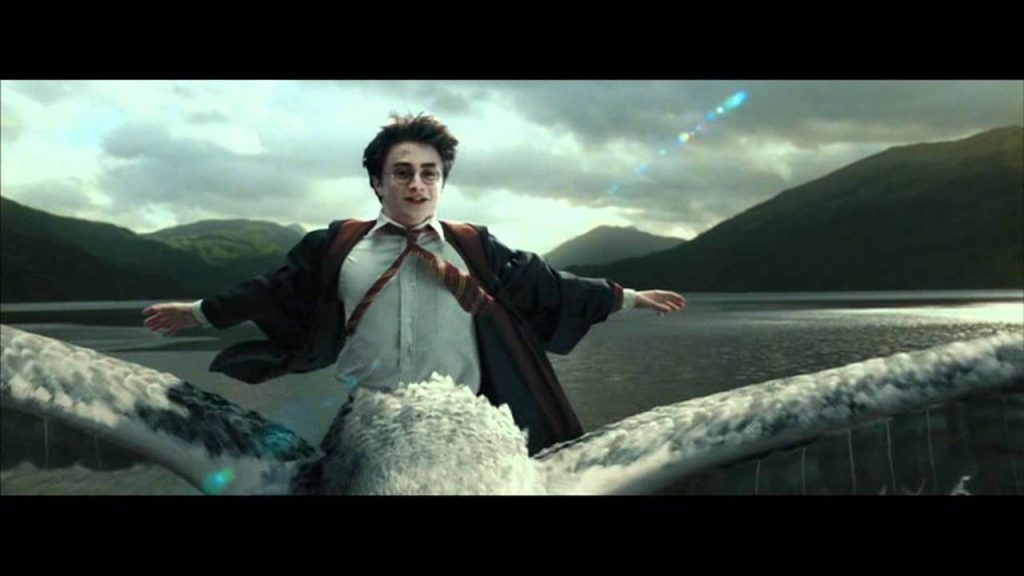

Again, this notion is reinforced in Buckbeak’s flight. At the instant where he takes off, the camera adopts a low angle, encompassing the full domineering stance of the creature as he soars over the crowd. Coupled with the intense drum roll and ascending, resplendent musical score, this works to establish not only the powerful status of Buckbeak, but similarly to stimulate the audience’s admiration and appreciation of the creature’s splendour. This moment is followed by fluid, prolonged, wide and panning shots, in which the use of both CGI and Steadicam visualise the motions of Harry and Buckbeak’s flight through the highland landscape. (Figure 3) The gracefulness of this sequence, combined with the impressive sublimity of this natural aesthetic, again represents the majestic, dignified and prodigious nature of Buckbeak. This perception is reinforced as, flying at low level over the river, Buckbeak elegantly reaches his claw out into the water. (Figure 4) Surrounded by dappled sunlight, this produces a magical aesthetic, again adorning the animal with an imperial status. This picks up on Harry Potter’s tendency to allude to contemporary medievalism: the similarity between Buckbeak and the legendary griffin, a regal creature which is half eagle and half lion, heraldically links the hippogriff to a subtext of royalty. Recognition of this resemblance therefore bestows the audience with a sense of awe towards his presence. Moreover, this scene additionally draws attention to the constructive nature of the bond between Harry and Buckbeak. Riding on the creature’s back, Harry extends his arms: a position which distinctly mirrors Buckbeak’s own outstretched wings. (Figure 5) This replays Leonardo DiCaprio’s illustrious scene in James Cameron’s Titanic, consequently conjuring the visual code which accompanies this for a certain emotional eruption. The framing here thus visually connects the characters, while it simultaneously self-consciously draws the audience’s attention to the more profound connotations of this link. Both the majesty of the creature, and the established unity between he and Harry, generate an allegorical presence. Here Buckbeak, as representative of the animal kingdom; and the young wizard of a typical human teenager, draw attention to a contest against the binary between humans and animals in the real world. Through this, and Buckbeak’s later act of liberation toward Sirius, the audience are led not only to question common perceptions of human-animal ranking, but also to consider whether similar respect for animals in the real world could be equally as constructive.

Figure 3: Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban – Harry and Buckbeak fly over the open landscape

Figure 4: Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban – Buckbeak dips his claw in the water

Figure 5: Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban – Harry, with arms outstretched, mirrors Buckbeak

Overall, the representation of Buckbeak and his relationship with Harry in the film, are linked symbolically to a contest against human’s domineering status over animals in society. Effective employment of shot composition, framing and sound, highlight the remarkable nature of the hippogriff, as a result stimulating the audience’s respect and admiration for the animal. Simultaneously, these devices awaken viewers to the manipulative presence of the director, consequently making manifest the more profound connotations of these elements. For example, the visual power and majesty of Buckbeak conveyed throughout the film, is used to alert viewers to the frequently misjudged pecking-order between humans and animals. Thus society is made aware of the need both to treat animals with greater respect, and subsequently to question typical ideas of human-animal hierarchy. The film does however complicate this issue through featuring human-animal transformations: namely those of Sirius Black’s alternate persona as a sinister black dog; and Remus Lupin’s mutation into the form of a werewolf. Through these instances of metamorphosis, the human and animal worlds are connected and equalised. Unlike the representations of Buckbeak, these animal instances signify the immoral side of these characters, thus acknowledging that, like humans, animals are not wholly omnibenevolent. Holly Batty similarly comments upon this in her analysis: ‘Through Harry’s numerous encounters with creatures…that defy species boundaries,…the reader [is urged] to reconsider the social ordering between human and nonhuman animals within the…real world.’[vi] With this in mind, animal presences in the film are seen to collectively promote, through their challenge to both common perceptions of animals, and of species binaries, the overall diminishment of hierarchical distinctions between humans and animals. Via the means of fantasy, viewers are therefore awoken objectively to both the possibility, and benefits of, cooperative human-animal relations in the real world.

To me, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban possesses many similarities to How to Train Your Dragon. Generically similar to Harry Potter, the film adopts characteristics from the fantasy, adventure, and family genres, while being comparably peppered with representations of mythical animals. How to Train Your Dragon depicts a young adolescent Viking’s pursuit of identity. Failing in his aspirations to become a dragon slayer, like other members of his tribe, Hiccup instead befriends the beasts, recognising the beauty of, and thus the need to protect these creatures. Reminiscent of the connection between Harry and Buckbeak, the charming relationship between Hiccup and Toothless, and the boys’ like-determination to free the beasts, rouses the audience’s sympathy and respect for these animals. Through this, the viewers are awoken to the more profound connotations of this human-animal bond: in particular its foregrounding of the need to reassess society’s perception of the human-animal hierarchy. As with Buckbeak, the emphasis placed upon the beauty of Toothless, through his fantastical and mythically-powerful status, draws attention to society’s preoccupation with animals as merely profit or threat to humanity, and thus to the need to advocate for their appreciation as equally entitled species.

Bibliography:

Batty, Holly, ‘Harry Potter and the (Post)human Animal Body’, Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, 53 (2015), 24-37

Lane, Cara, ‘The Prisoner of Azkaban: A New Direction for Harry Potter’, Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies, 35 (2005), 65-67

Zipes, Jack, ‘Why Fantasy Matters Too Much’, The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 43 (2009), 77-91

Filmography:

‘Creating the Vision’, DVD extras, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, dir. by Alfonso Cuarón, (Warner Bros., 2004) [on DVD]

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, dir. by Alfonso Cuarón, (Warner Bros., 2004) [on DVD]

Metafeller, ‘Harry Potter Meets With Buckbeak’, YouTube (2012), <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MKbr3o36IpY> [Accessed 21 November 2015]

MovieClips, ‘Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban Official Trailer #1 – (2004) HD’, YouTube (2011) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lAxgztbYDbs> [Accessed 21 November 2015]

Further Reading:

Batty, Holly, ‘Harry Potter and the (Post)human Animal Body’, Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, 53 (2015), 24-37

Lane, Cara, ‘The Prisoner of Azkaban: A New Direction for Harry Potter’, Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies, 35 (2005), 65-67

Rainer, Peter, ‘Fright of Passage’, New York Movies (2004) <https://nymag.com/nymetro/movies/reviews/9213/> [Accessed 13 November 2015]

Rowling, J.K., Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, (London: Bloomsbury, 2014)

Time Out London, ‘Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban’, Time Out London (2004) <https://www.timeout.com/london/film/harry-potter-and-the-prisoner-of-azkaban> [Accessed 13 November 2015]

Further Viewing:

‘Care of Magical Creatures’, DVD extras, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, dir. by Alfonso Cuarón, (Warner Bros., 2004)

‘Conjuring a Scene’, DVD extras, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, dir. by Alfonso Cuarón, (Warner Bros., 2004)

‘Creating the Vision’, DVD extras, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, dir. by Alfonso Cuarón, (Warner Bros., 2004)

How to Train Your Dragon, dir. by Dean DeBlois and Chris Sanders, (DreamWorks Animation, 2010)

[i] MovieClips, ‘Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban Official Trailer #1 – (2004) HD’, YouTube (2011) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lAxgztbYDbs> [Accessed 21 November 2015]

[ii] Jack Zipes, ‘Why Fantasy Matters Too Much’, The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 43.2 (2009), 77-91, (p.79)

[iii] Cara Lane, ‘The Prisoner of Azkaban: A New Direction for Harry Potter’, Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies, 35.1 (2005), 65-67 (p.67)

[iv] ‘Creating the Vision’, DVD extras, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, dir. by Alfonso Cuarón, (Warner Bros., 2004) [on DVD]

[v] Metafeller, ‘Harry Potter Meets With Buckbeak’, YouTube (2012), <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MKbr3o36IpY> [Accessed 21 November 2015]

[vi] Holly Batty, ‘Harry Potter and the (Post)human Animal Body’, Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, 53.1 (2015), 24-37, (p.25)