Figure 1: Kubo lifted in the air by wings made of origami birds.

Kubo and the Two Strings follows a boy whose life is made even more extraordinary when a perilous adventure, which his mother has tried to save him from, accidentally finds him. Kubo can tell stories using the magical music of his shamisen to animate origami creations. Also, his grandfather is the Moon King, who wishes to steal Kubo’s eyes. He already has one of them, which is why Kubo and his mother hideout in their remote cave home in Japan. But when Kubo breaks his mother’s number one rule and stays out at night-time, he is discovered by his aunts who work with the Moon King and so he must run. This is where the film’s imagination takes flight: with Kubo’s adventure to find the mythical armour which will protect him from his grandfather. This would be an impossible task without the help of a monkey statue come to life, a beetle-samurai man, and Kubo’s paper animals.

As a stop-motion animation, this film is as detailed and carefully crafted as Kubo’s origami. Laika studios are experienced in this style, having also produced films such as Coraline and The Box Trolls. Their films often include magical or strange creatures and are all made with a slow process involving moving puppets pose by pose. Kubo and the Two Strings aims to delight families with the quirky toy-like look of the characters, combined with the technological magic of moving origami and talking animals.

Figure 4: An in depth look at how the film was made, as told by director Travis Knight. [1]

This film evaluates the role that animals play in human stories and how they are characterised by these tales. Kubo’s most valued relationship is with Monkey, who evolves from a small wooden statue, into a real snow monkey infused with his mother’s spirit. From the beginning, the mother instructs Kubo to always keep the statue nearby for protection. The statue is only animated by the character’s moving it, such as when the mother holds the statue, shaking it side to side and putting on a deep voice to tell Kubo the rules he must follow about being home before dark. Kubo’s first interaction is rocking the statue side to side with his finger when he cannot sleep. It symbolises the mother’s protection by always being with Kubo even when she cannot be, as she assumes a sleep-like state for most of the day after being harmed when escaping her father. Kubo sees Monkey alive for the first time after fleeing the battle between his mother and her sisters, implying his mother lost and transferred her spirit to the statue as a last measure. The camera takes Kubo’s viewpoint as his eyes open to a snow-filled world and Monkey slowly comes into view, her face filling the screen and looking towards him. The shot is extremely close and each tuft of fur that has been crafted so it sticks out is unmissable and the audience can truly visualise the shift from smooth wooden statue to real furry creature. The snowflakes blur past her white fur and pink face, disappearing into the white background, creating a visual blank-slate, as this is the scene where the characters start anew, and the monkey-mother is re-born.

Figure 6: The first look at Monkey alive.

Figure 7: Monkey’s fur all ruffled up.

As the film progresses, it becomes clear this character is entirely the mother but in an alien, animal body. Monkey’s every emotion, and her smart and caring personality originate from the mother, not from being a monkey. Author Katherine Rundell asks ‘’what is the bite of animal stories?’’, well, they are used ‘‘to convey our ideals under cover of animal faces’’.[3] This film’s sole representation of a monkey is actually something else entirely, a human ‘‘under cover’’ of a monkey’s furry, pink face. This allows a way for the mother’s story to continue. She can join her son’s journey, nurture him through it, and see him grow, in a way she could not in her fragile human state. After Kubo finds out the truth, Monkey tells him how she met his father, visually recreating the story with Kubo’s origami. Monkey sits to the right, while the origami representations of her human self and Kubo’s father acts out her unfolding story to the left. This is a visually jarring sight. Monkey tells the story first person, because she is the mother in essence, yet the paper is visually more accurate with its human form and so the ‘I’ seems wrong coming from a monkey’s mouth. The monkey is essentially a token of the mother’s love and desire to protect Kubo, acting out and voicing her wish to be part of his story.

Figure 9: The monkey statue.

Figure 10: Monkey sat like a statue.

Figure 11: A Japanese macaque, or snow monkey, sitting down. By Maciek Pożoga. [5]

The animators try to prevent Monkey from only being viewed as the mother in a costume, by making her act like a real monkey supposedly does. Animal behaviours are not just performed but it appears she is really overcome by instincts. While cooking for Kubo, Monkey picks something from her fur to eat. The shot cuts to Kubo, with eyes wide in shock and disgust at this action, then focus jumps back to Monkey who is now scratching herself with her leg. She catches Kubo’s stare and stops, becoming wide eyed herself in embarrassment at being watched. There is conflict between the impulses of the monkey and human, because the mother is self-conscious enough to be embarrassed of such actions, but she performs them instinctively without thought, until another human thinks it is strange. Rather than distinguishing Monkey from mother, there is a confusion of human and animal with these actions, which ties the film to what Paul Wells entitles ‘‘The Madagascar Problem’’.[6] He argues that ‘’animated animal narratives essentially remain coherent and plausible so long as they retain the inner logic that informs the anthropomorphic intentions and outlook of the characters’’.[7] But by mixing human and animal in Monkey’s character, the animators create some confusion, including for the character herself. She has a human consciousness and an animal body which results in monkey-like actions alongside an awareness these actions seem strange to Kubo. However, he believes her to be a real monkey at this point so her actions should seem natural.

The film later introduces, Beetle who seems to ‘’retain the inner logic’’ by being the most self-aware of the animal characters. He is an anthropomorphic beetle, a samurai, and Kubo’s father but suffering memory loss and a bodily transformation making him unaware of this fact. The visual combination and confusion of these identities results in human facial features, a tall stature, and six limbs, making Beetle appear as a ‘’giant spiky insect monster’’ when Monkey first sees him.[8] He sometimes behaves in a beetle-like way, by scuttling up a wall on all legs or getting stuck on his back rocking forwards and backwards. The camera cuts to Kubo and Monkey watching him struggle with confused expressions, showing his position is unexpected, because they did not see him as a helpless insect, and he is not. He (sometimes) has much more awareness than Monkey and points out their differences compared to regular animals. When bickering, Monkey calls Beetle a ‘’talking cockroach’’ and he retorts: ‘’this coming from a talking monkey.’’[9] He recognises what normal animals should be like, and what they should not be is ‘’talking’’ and acting like him and Monkey. She intends to insult him by calling him the wrong type of insect and highlighting his strangeness, but her insult falls flat because it is impersonal, as he knows he is not really a beetle or any insect at all. She does not see the irony of ‘’this’’ comment when she herself is just as strange and abnormal. The visuals of a tall beetle creature arguing with a monkey on a beach reinforces this. Using Beetle, the filmmakers point out the inconsistencies of both the human-animal characters, positioning them as unique cases meant to embody the magic of the film. They are essentially humans displaced in unfamiliar bodies so their confusion about themselves and the way they act is purposeful.

Kubo’s origami animals are brought to life by human need: the need for the entertainment which stories provide. The origami illustrates how in this film, representations of animals are visible and valued much more than the real. In a film review, Aja Romano summarises that ‘Kubo is a story about stories’ but more specifically, as shown by the shapes the origami most often takes, it is about telling stories of animals.[11] Kubo performs in a village near to his home, where animal stories are a part of everyday life. When Kubo walks into the village, the camera cuts to a dragon’s face filling the screen with an angry expression, before zooming out to show the whole puppet being moved by a man who delights in exciting (and scaring) the children with his performance. Dragons are seen as fascinating, fierce, and consequently perfect for stories. Sitting side by side with an elderly woman in the village, Kubo shares that his upcoming story will contain ‘’the usual’’, which is code for ‘’monsters.’’[12] The woman immediately guesses this, illustrating that they make the most impressive and extraordinary stories, and are popular to the point where they become seen as ‘’usual’’, normal and expected. One sound from the shamisen draws gasps and cheers from the villagers, and the puppeteer even turns his dragon to face Kubo, giving his attention but not quite finished with his own story yet. Inspired by the villagers’ favourite stories, Kubo creates a range of varyingly menacing beasts from a spider to a shark, and a fire-breathing chicken. The events create a daze-like enchantment over the viewers, as paper flies in and out of the shot and Kubo is seen pacing from overhead, playing his music with increasing intensity all while the sun dims with passing time. Audience reactions are caught up close: a father shields his daughter’s eyes as paper is sliced, a man cheers enthusiastically, and one spectator puts a hand over his mouth to prevent vomiting as the paper guts of a creature hit him. So convincing and captivating is the story that the paper animal feels real to him, and he is sickened by the ‘death’ of it. His reaction is silly and excessive as he confuses paper and reality, but he is not the only one to make such a mistake.

Figure 15: The face of a dragon puppet.

Figure 16: A fire-breathing origami chicken

Kubo decides to make mischief by confusing a bird with its paper counterpart. The bird is peacefully singing in the sky, but looks to the side, notices the origami, screeches, flaps its wings, and zooms off the screen. The camera angles change repeatedly to follow as the real bird flies and loops and eventually faces its inescapable paper shadow, flapping its wings in intimidation. It perceives the paper as a threat, because it is unnatural and makes no sound or move of its own accord. It copies the real bird, or rather, follows Kubo and his music as he wills it to act. For Kubo, the entertainment of this spectacle is worth the distress he causes by teasing the bird. His animals are more important and feel more real to him.

Figure 18: A bird meets its origami copy.

Figure 19: Spot the difference: the real bird being followed by many paper birds.

Animals in this film are material for stories, much like the paper used for origami. They are flat and inanimate until given shape and meaning by humans. The origami is crafted by Kubo to delight his viewers, who temporarily feel the story and animals to be real, whereas the real animal, the bird, senses the imitation. Monkey and Beetle are similar imitations but with human rather than paper at their core. Neither can capture the reality of the animal they appear to be, but then again, reality is not truly desired by the film, only representations to help Kubo on his adventure.

Kubo and the Two Strings looks at the relationship of animals to human storytelling. Wielding his stories, an animal can be anything Kubo wants it to be. A monkey can be a fierce, loving guardian, a beetle is a protective warrior, and a chicken becomes a fire-breathing monster. Disney’s Brother Bear also depicts a human who becomes an animal but uses this plot to offer a more balanced picture by exploring how a bear’s understanding of itself differs from a human’s point of view.[14] Whereas in Kubo and the Two Strings, the animals are animated by, and for, humans.

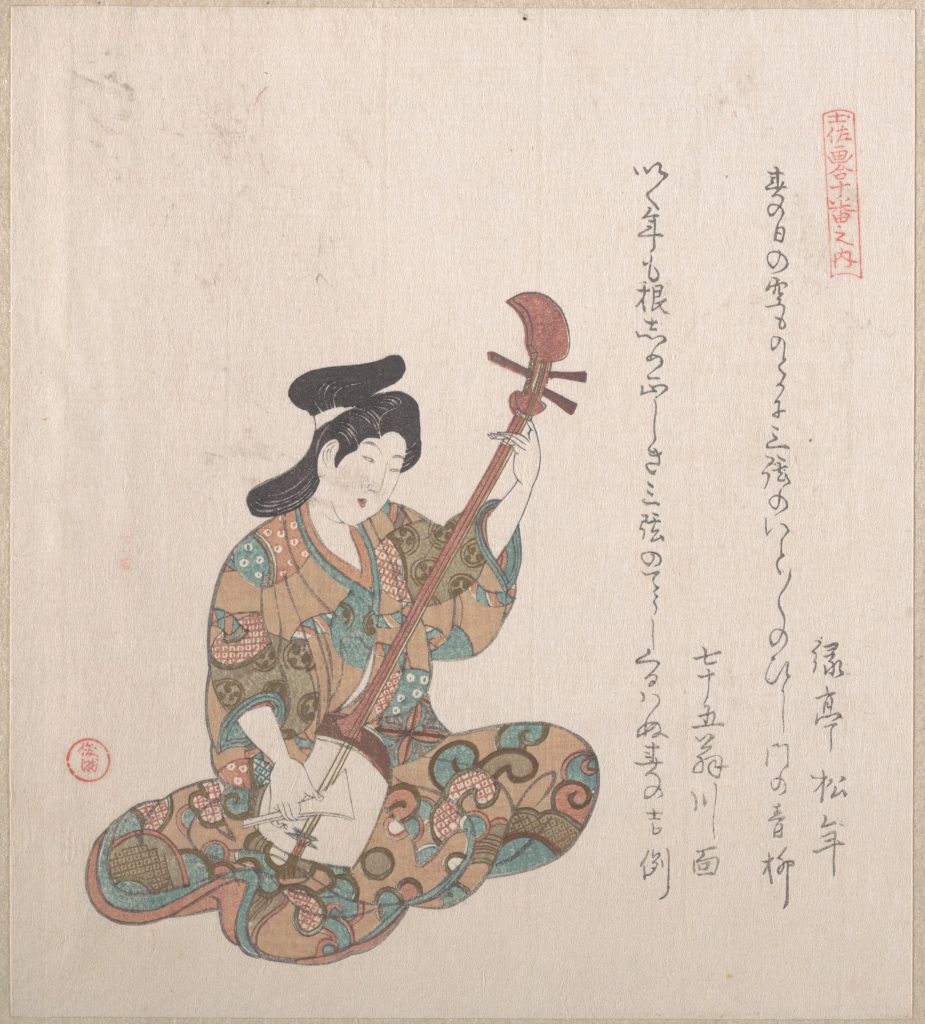

Figure 21: Artwork. Woman Playing on the Shamisen by Kubo Shunman. [16]

Figure 22: Woman Tuning a Shamisen and a Cat Looking at its Own Reflection by Yashima Gakutei. [17]

Footnotes:

[1] BBC Click, Behind the scenes of Kubo and the Two Strings – BBC Click, online video recording, YouTube, 9 September 2016 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JncuykDwT8A> [accessed 19 January 2023]

[2] Coraline, dir. By. Henry Selick (Laika Studios, 2009).

[3] Katherine Rundell, ‘Stories with teeth: How animal tales help us understand humans’, The Guardian, 2022 <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/dec/10/stories-with-teeth-how-animal-tales-help-us-understand-humans> [accessed 19 January 2023].

[4] LAIKA Studios, Puppet Featurette: Monkey – Kubo and the Two Strings | LAIKA Studios, online video recording, YouTube, 3 November 2022, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6bCaqa_81c> [accessed 19 January 2023].

[5] Crair, Ben and Maciek Pożoga. digital photograph, ‘What Japan’s Wild Snow Monkeys Can Teach Us About Animal Culture’, Smithsonian Magazine, 2021 <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/japan-wild-snow-monkeys-teach-scientits-how-animals-pass-skills-180976488/> [accessed 19 January 2023].

[6] Paul Wells, ‘Introduction: The Kong Trick’, in The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture, (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2008), pp.1-25 (p.22). ProQuest Ebook Central ebook.

[7]‘Ibid.’

[8] Kubo and the Two Strings, dir. By Travis Knight (Laika Studios, 2016).

[9] ‘Ibid.’

[10] LAIKA Studios, “Beetle vs Monkey” Evolution of a Scene – Kubo and the Two Strings | LAIKA Studios, online video recording, YouTube, 26 April 2022, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=svHFPU-nzTY> [accessed 19 January 2023].

[11] Aja Romano, ‘Kubo and the Two Strings is a gorgeous stop-motion homage to Kurosawa and the power of stories’, Vox, 2016 <https://www.vox.com/2016/8/19/12520870/kubo-and-the-two-strings-review-kurosawa> [accessed 19 January 2023].

[12] Kubo and the Two Strings, dir. By Travis Knight (Laika Studios, 2016).

[13] Kaushik Patowary, ‘Akira Yoshizawa: The Master of Origami’, Amusing Planet, 2012 < https://www.amusingplanet.com/2012/03/akira-yoshizawa-master-of-origami.html> [accessed 19 January 2023].

[14] Brother Bear, dir. By. Aaron Blaise and Robert Walker, dir., (Disney, 2003).

[15] Focus Features, Regina Spektor – “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” – Official Video (From Kubo And The Two Strings), online video recording, YouTube, 10 August 2016 < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8hUOKjy-9-o> [accessed 19 January 2023].

[16] Kubo Shunman, Woman Playing on the Shamisen, 1815, ink and colour on paper, 20.2 x 17.9 cm, <https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/54050> [accessed 19 January 2023].

[17] Yashima Gakutei, Woman Tuning a Shamisen and a Cat Looking at its Own Reflection, c.1820, ink and colour on paper, 20.8 x 18.6 cm, <https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/54124> [accessed 19 January 2023].

Bibliography:

BBC Click, Behind the scenes of Kubo and the Two Strings – BBC Click, online video recording, YouTube, 9 September 2016 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JncuykDwT8A> [accessed 19 January 2023]

Blaise, Aaron and Robert Walker, dir., Brother Bear (Disney, 2003)

Crair, Ben and Maciek Pożoga, digital photograph, ‘What Japan’s Wild Snow Monkeys Can Teach Us About Animal Culture’, Smithsonian Magazine, 2021 <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/japan-wild-snow-monkeys-teach-scientits-how-animals-pass-skills-180976488/> [accessed 19 January 2023]

Focus Features, Regina Spektor – “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” – Official Video (From Kubo And The Two Strings), online video recording, YouTube, 10 August 2016 < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8hUOKjy-9-o> [accessed 19 January 2023]

Gakutei, Yashima, Woman Tuning a Shamisen and a Cat Looking at its Own Reflection, c.1820s, ink and colour on paper, 20.8 x 18.6 cm, <https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/54124> [accessed 19 January 2023]

Knight, Travis, dir., Kubo and the Two Strings (Laika Studios, 2016)

LAIKA Studios, “Beetle vs Monkey” Evolution of a Scene – Kubo and the Two Strings | LAIKA Studios, online video recording, YouTube, 26 April 2022, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=svHFPU-nzTY> [accessed 19 January 2023]

LAIKA Studios, Puppet Featurette: Monkey – Kubo and the Two Strings | LAIKA Studios, online video recording, YouTube, 3 November 2022, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6bCaqa_81c> [accessed 19 January 2023]

Patowary, Kaushik, ‘Akira Yoshizawa: The Master of Origami’, Amusing Planet, 2012 < https://www.amusingplanet.com/2012/03/akira-yoshizawa-master-of-origami.html> [accessed 19 January 2023]

Romano, Aja, ‘Kubo and the Two Strings is a gorgeous stop-motion homage to Kurosawa and the power of stories’, Vox, 2016 <https://www.vox.com/2016/8/19/12520870/kubo-and-the-two-strings-review-kurosawa> [accessed 19 January 2023]

Rundell, Katherine, ‘Stories with teeth: How animal tales help us understand humans’, The Guardian, 2022 <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/dec/10/stories-with-teeth-how-animal-tales-help-us-understand-humans> [accessed 19 January 2023]

Selick, Henry, dir., Coraline (Laika Studios, 2009)

Shunman, Kubo, Woman Playing on the Shamisen, 1815, ink and colour on paper, 20.2 x 17.9 cm, <https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/54050> [accessed 19 January 2023]

Wells, Paul, ‘Introduction: The Kong Trick’, in The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture, (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2008), pp.1-25. ProQuest Ebook Central ebook

Further Reading:

Barnes, Simon, The History of the world in 100 Animals (London: Simon and Schuster, 2020)

Fraser, Lucy, ‘Dogs, Gods, and Monsters: The Animal–Human Connection in Bakin’s Hakkenden, Folktales and Legends, and Two Contemporary Retellings’, Japanese Studies, 38.1 (2018) 103-123 <http://dx.doi.org10.1080/10371397.2018.1448972>

Miyazawa, Kenji, Night Train to the Stars:Beloved, Enigmatic Japanese Folk Tales. Trans. by John Bester (London: Vintage Classics, 2022)

Ortabasi, Melek, ‘(Re)animating Folklore: Raccoon Dogs, Foxes, and Other Supernatural Japanese Citizens in Takahata Isao’sHeisei tanuki gassen pompoko’, Marvels & Tales, 27.2 (2013) 254-75 <http://dx.doi.org/10.13110/marvelstales.27.2.0254>

Shaw, Matthew, ‘Thinking with Animals’, British Library, 2015 <https://www.bl.uk/animal-tales/articles/thinking-with-animals> [accessed 19 January 2023]

National Gallery of Art, ‘Animals in Japanese Folklore’, National Gallery of Art, [n.d.] <https://www.nga.gov/features/life-of-animals-in-japanese-art.html#top> [accessed 19 January 2023]