The woods are getting smaller every day.

At the core of 2020’s Wolfwalkers is a fable about environmental degradation: the mounting destruction of the natural world, and the subjugation of those who live in tune with it. From its very beginning, the film seeks to examine and even disrupt the human/animal boundary in a unique way. Whilst many of the human characters seek to enforce this boundary (and their own sense of superiority) through the violent subjugation of nature, the film ultimately proves that there is animality within us all. In doing so, it highlights that the oppression and destruction of the ‘animal’ world equally harms the human-animals who cause it, a powerful message about our real-life climate crisis. These major themes are highlighted in the film’s iconic opening sequence, which viscerally demonstrates the process of ecological destruction.

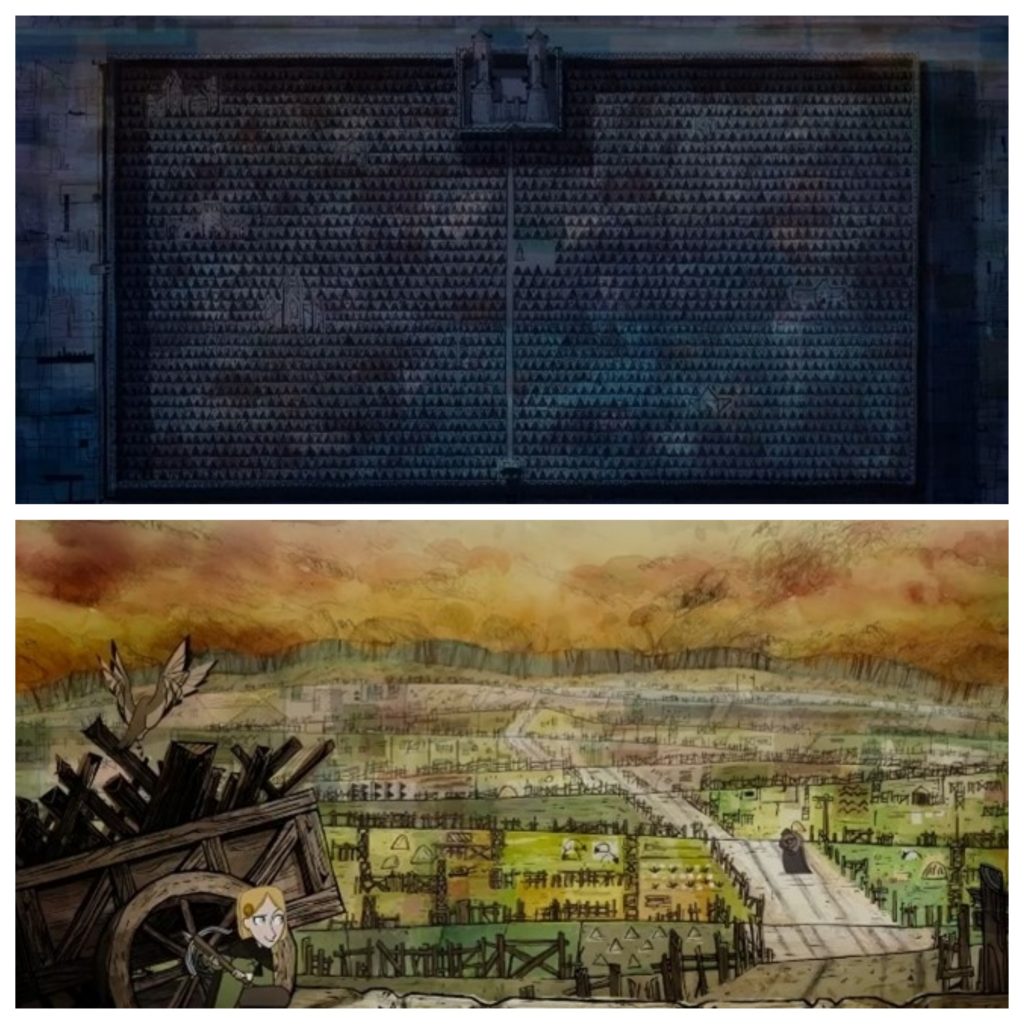

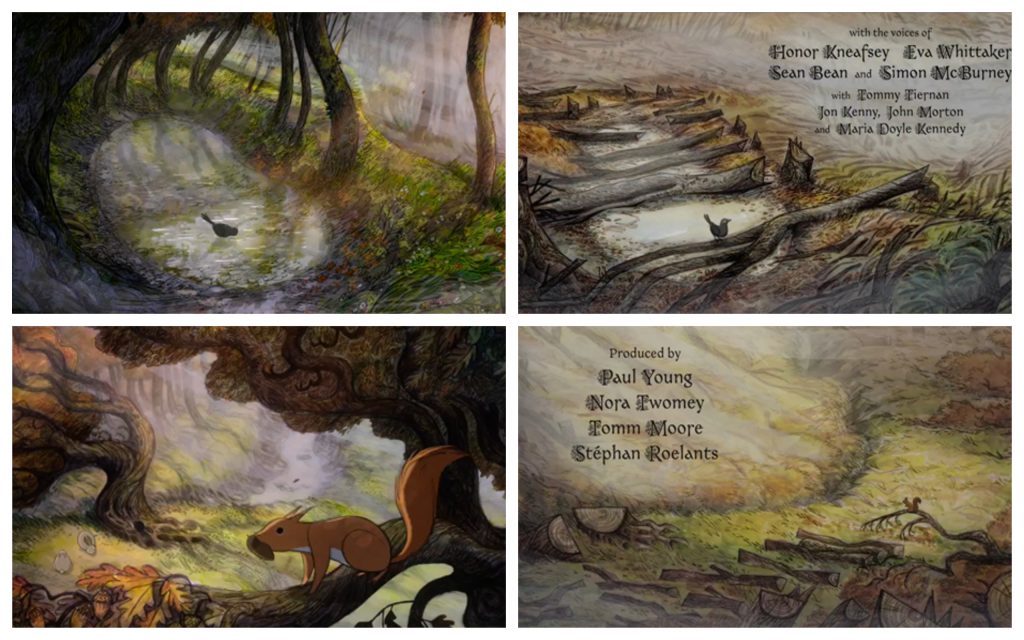

The opening frames of the film shutter between vignettes of woodland animals, each captured in their natural setting. The soundscape mixes Bruno Coulais’ original score for the film (the gentle but unnerving Wolfwalker’s theme) with diegetic woodland sounds, highlighting both the mystical beauty and the fragility of nature. This montage of natural life is disrupted by the sharp swing of an axe through the frame; soon followed by even more weapons, as a spear wielding army is sent to raze the forest. This immediately introduces the first form of human/animal relations the film explores – those humans who deny their own animality, and thus, live at odds with the natural world. Those humans who embrace their animality (the literal Wolfwalkers, residents of the forest) are persecuted by the reinforcement of this assumed hierarchy, as much victim to the ecological destruction as the non-human animals they live alongside. As is unfortunately true of the real climate crisis, the most devastating consequences of environmental exploitation are first felt by the most vulnerable humans and animals.

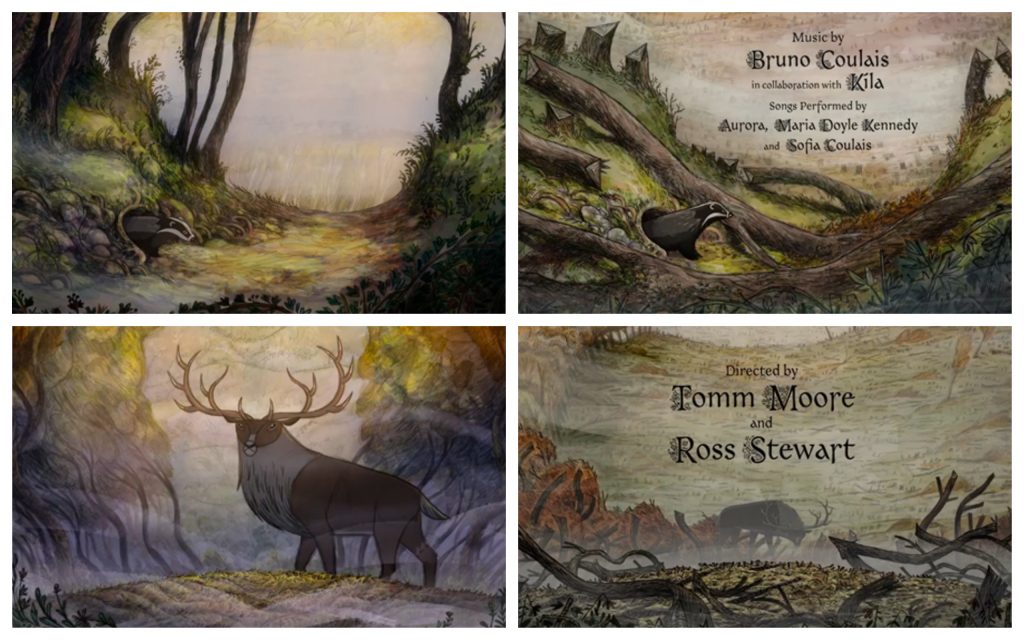

The film’s following sequence only further highlights the destruction these human soldiers have wielded. In a dark mirror of the opening montage, the film returns to each of the woodland animals, struggling to survive as their habitats lay destroyed around them. The film’s purposeful and unusual animation style emphasises this destructive process, as the once uniformly curved shapes of the woods begin to give way to sharp, jagged lines – straightened to sharp points by the blows of the axe. This use of straight and geometric lines is used consistently to depict the town; the style becoming visually synonymous with the urban and denaturalised centre of human command. This destructive ordering gradually breaches the boundaries of the woods, slowly erasing more and more natural and animal life. The only non-human animals left remaining are those deemed ‘useful’ and controllable – the rest fall as either collateral damage of human expansion, or like the wolves, are intentionally hunted to protect human interests.

The ecological issue of deforestation is thus explored in the film using both human and non-human animals. The destruction of the forest is emphasised by its effects on the animals who reside there; effects that the film silently draws attention to in its framing. The filmmakers have stated that they didn’t want the animals to be too ‘human’ or typically ‘cartoony’, but rather, to be visually expressive whilst retaining their core animality.[1] The second, parallel montage of woodland life achieves this expressiveness through its framing of the animals within. Both the squirrel and the stag are moved from the foreground to the background of these second shots, dwarfing them in their destroyed environments. The stag – the archetypal ‘King of the Forest’ – now has his head bowed, as he stares directly at the audience in a silent and subdued plea. Human animals (the titular Wolfwalkers) are highlighted as further victims of expansion, but simultaneously, the film very explicitly presents both the ‘Wolfwalkers’ and the wolves as forces of healing and protectors of the natural world. The film’s main conflict is therefore between two very distinct forms of animal-human relations: humans who embrace their own animality and live-in tune with nature, and humans who suppress and destroy it.

[1] IndieWire, ‘Wolfwalkers’ Ross Stewart and Tomm Moore’, IndieWire, 2021, <https://www.indiewire.com/influencers/wolfwalkers-tomm-moore-ross-stewart> [accessed 10 November 2021]

Figure 1: Mauro Pimentel, Amazonia rainforest in Labrea, digital photograph, Wired, 2nd December 2021, < https://www.wired.co.uk/article/end-deforestation-2030> [accessed 13 January 2022].

Figure 2: Rich Carey, Newly logged Malayasia rainforest, digital photograph, GLP, 19th October 2019, <https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2020/10/19/rewilding-farmland-can-protect-biodiversity-and-sequester-carbon-new-study-finds/>[accessed 13 January 2022].

Figure 3: Dennis Finley, Landfill, digital photograph, National Geographic, <https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/pollution/> [accessed 13 January 2022].

Figure 7: Alex Wong, Indigenous Protest of the DAPL, Grist, 3rd May 2021, <https://grist.org/protest/pipeline-protest-laws-montana-kansas-arkansas/> [accessed 13 January 2022].