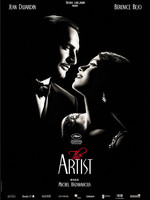

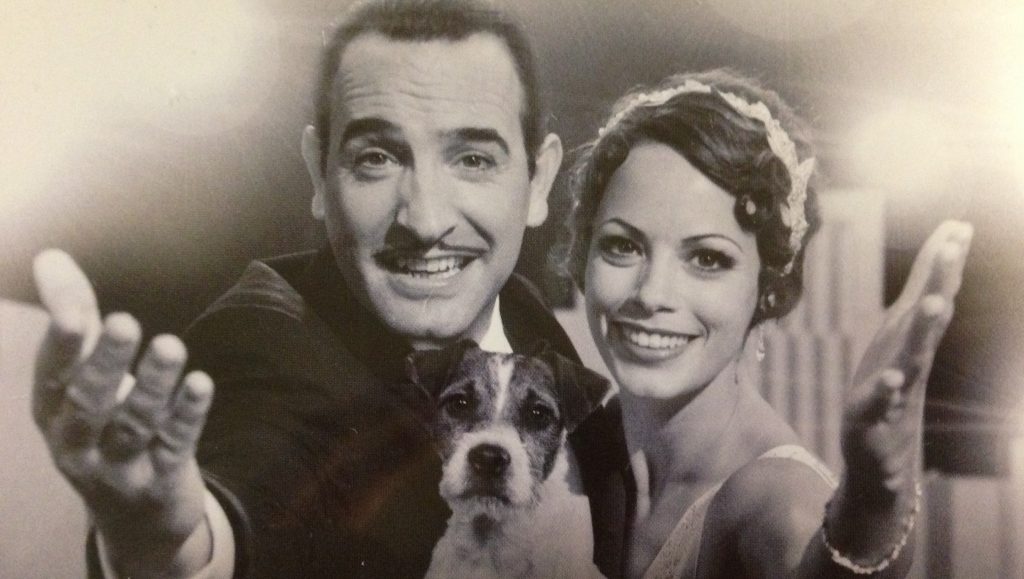

Jean Dujardin as George Valentin, Bérénice Bejo as Peppy Miller and Uggie the dog in The Artist

The Artist (2011) is a remarkable modern day silent film that explores the transformation of silent movies into talking pictures in 1920s Hollywood. This change in cinema style affects the lives of both the famous silent movie actor George Valentin (Jean Dujardin), and the up-and-coming actress Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo); but in very different ways. George, partnered with his sidekick dog (Uggie), is a prominent star in the silent movie business, making picture after picture. Yet, with the introduction of the sound in cinema, Peppy strides up the stairs that George is descending. He once laughed at the prospect of talkies, but after years of being a nobody, the veteran suffers his fall in silence. Thanks to Uggie and Peppy, George is saved from himself and sees a new lease of life by partnering up with Peppy to do what they do best: tap-dancing.

Hazanavicius’ choice of making a silent feature length movie is truly admirable. The Artist sticks to technical traditional style, made in 1.33:1 aspect ratio and non-diegetic music as a tool to express emotion. Although Uggie may not have a prominent role in this film, he is essential to the main character’s life. When asked why use the dog in the film, Hazanavicius stated: ‘The dog is very important in the movie […] to me it was just cool to have a dog because he changed the profile of the main character and it was very period’.[1] In the era of silent movies, animal agency was used to create a heart-warming story. Everyone enjoyed this because ‘everyone had a dog’ and people loved the idea that their own dog would save the family.[2]

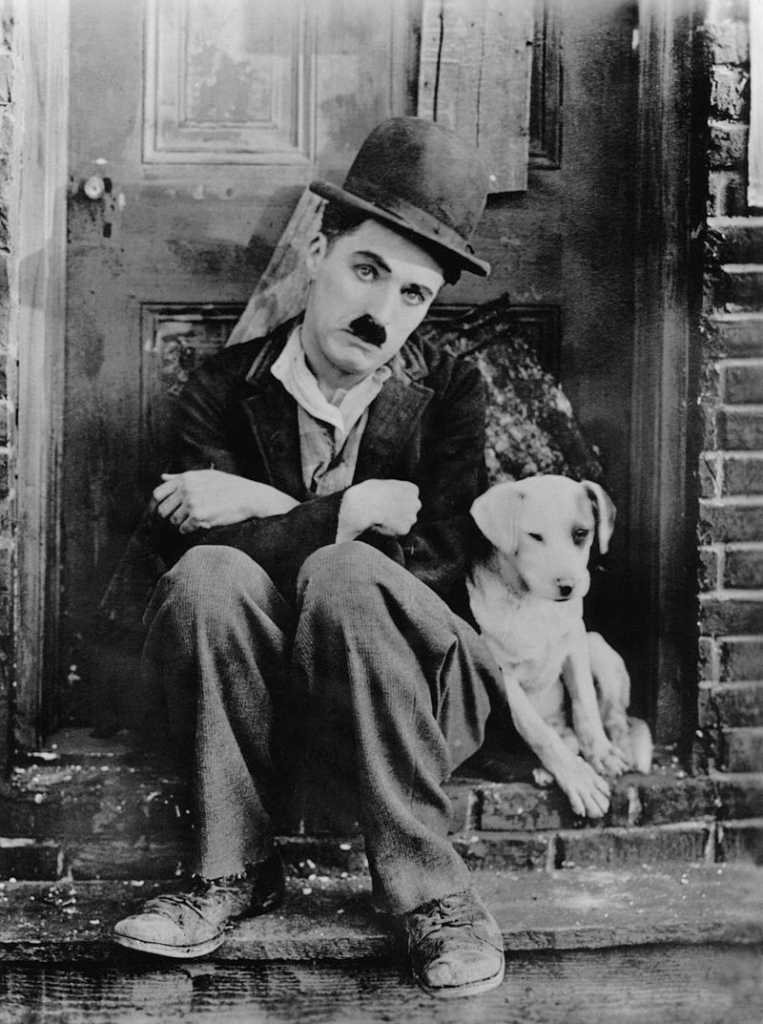

Charlie Chaplin as The Tramp and his dog in A Dog’s Life.

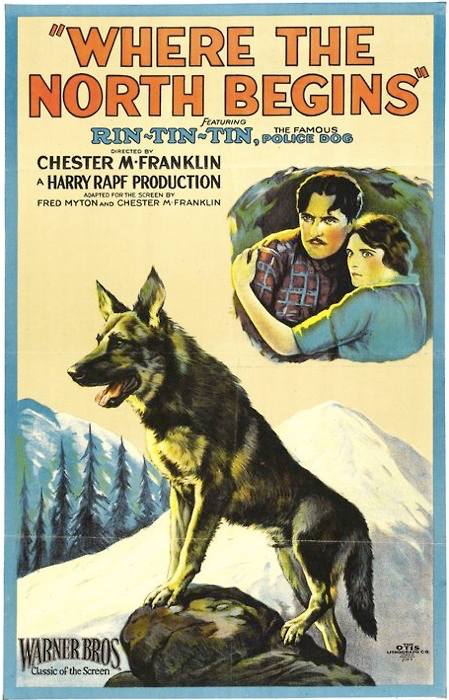

Movie poster of Where the North Begins

Dogs function in different ways across all genres of film. In silent movies, dogs have either the role of comedic release and/or the role of a hero; they are a tool for the audience to engage in either laughter or admiration. Dogs are involved in a slap-stick spectacle and this can be seen in Charlie Chaplin’s A Dog’s Life (1918). The dog helps create the human character’s wealth but also brings with him an infectious daftness. Chaplin stressed that a dog would be an asset in his works.[3] Dogs are brilliant for this kind of comedy because they are physically funny in their playful temperament and silent film is reliant on the visual to be funny. Uggie’s interaction with George is always physical and is often drawn on due to their master/pet relationship.

Dogs also commonly embodied heroic figures saving the familial unit, such as the sheepdog Blair in Rescued by Rover (1905). Or the more famous Rin Tin Tin, a heroic police dog starring in Where North Begins (1923). These stories are exciting yet also moving, audiences relate to them despite the absence of language because the dogs display heroism and loyalty, demonstrating that it is the physical that is entertaining, yet also the fidelity of human and animal relations. These famous dogs establish a cultural trope of heroic dogs in films.

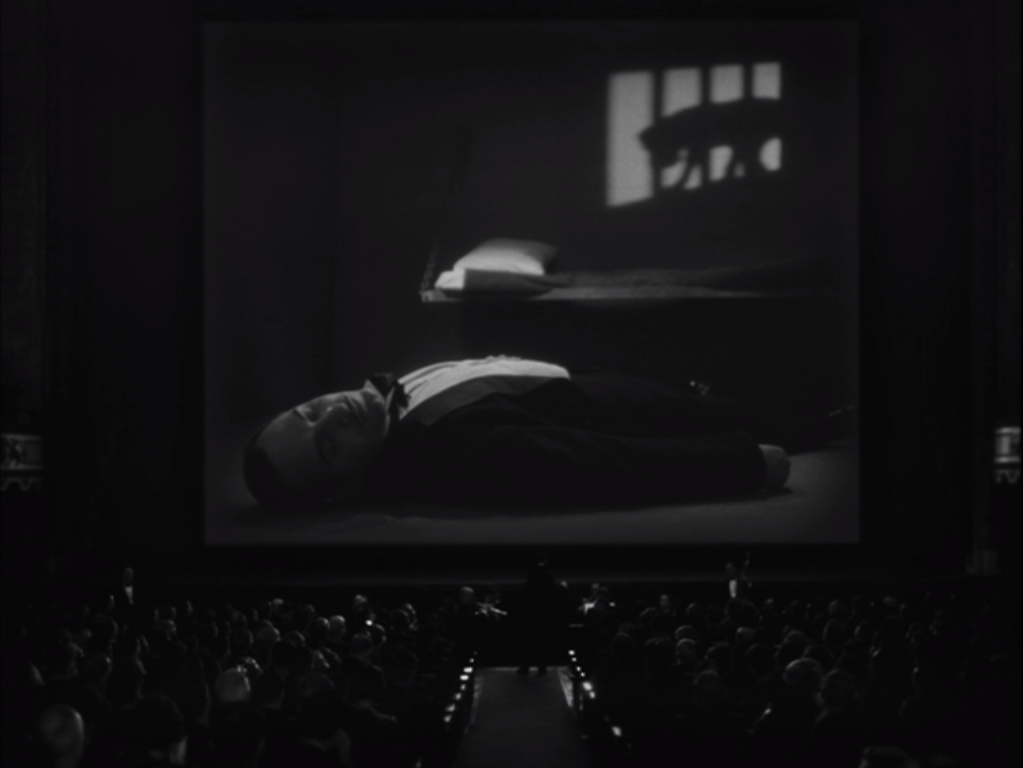

| Fig.1. Jean Dujardin as George Valentin lying in a prison cellwith Uggie in The Artist |

Uggie successfully fulfils both the roles of hero and comic. The opening scene of The Artist establishes the partnering of George and his dog act. We are watching a 1927 audience watch George Valentin on screen in a movie theatre. The pairing are famous together, but as the rest of the film demonstrates, this is not enough anymore. In his silent film, George is lying on a prison floor and a shadow of Uggie appears behind the shadow of prison bars (Fig.1). There is an effective overlapping and layering of images here, as the dog figure is a shadow, which is an image on a screen, which is then presented to us. After the screening of the film, George comes onto the stage and performs tricks with Uggie, and the audience enjoys his tricks of ‘shooting’ the dog as this is a comical and endearing use of Uggie (Fig.2). Non-diegetic, joyful xylophones accompany this scene, creating a lighthearted tone, establishing that master and dog are charming characters. This same ‘play-dead’ trick is duplicated at the end of the film, but in a darker situation. George does not commit suicide as he intended, but his gun still goes off in his hand. Uggie, used to ‘BANG!’ as a command for the trick to ‘play dead’, falls to the floor (Fig.3). This provides a comical release of tension, as both Peppy and George laugh at Uggie, lifting the potentially sad scene into one of humour. Uggie’s trick reminds the audience of the lighthearted tone at the beginning, implying that not all hope is lost for the duo.

| Fig.2. Jean Dujardin as George Valentin and Uggie the dog in The Artist | Fig.3. Uggie the dog performing ‘play dead’ trick in The Artist |

Uggie is again used as a comic relief in the breakfast scene with George and his wife. Doris (Penelope Ann Miller) is furious with George for appearing in a newspaper with Peppy, and George attempts to lighten the mood using Uggie. The dog is put on the table and they perform the same actions, mirroring each other, such as bending the head down to apologise (Fig.4). This ironic comic doubling satirises George’s sincerity because it is a performance of an apology. This scene exemplifies how trained dogs are entertaining. It is the playful interaction between human and dog that is enjoyable, and the respect for one another is evident. Hazanavicius argued that this is because Uggie represents a goodness in George because ‘you can’t help but love a character who is so loved by a dog like this. You know he’s a good person’.[4] Here, George cannot establish a connection with the audience without his animal counterpart, demonstrating that Uggie’s role within the film is more than just a comedic one. Uggie’s tricks are adorable and charm us into watching the both of them perform.

| Fig.4. Jean Dujardin as George and Uggie the dog in The Artist | Fig.5. Uggie the dog barking at Joel Murray as the policeman in The Artist |

We are also charmed by Uggie’s position as a hero, saving George from a house fire. George, in a mad rage, burns all his films in his apartment. This turns into a scene of chaos as the orchestral music increases tempo, with short sharp movements from the strings, creating a menacing tone that is reminiscent of the films George made. The camera cuts to Uggie, who shoots up in his basket, barking at George’s erratic behaviour. It is this close up that creates a communication between dog and owner which cannot be portrayed through sound. Uggie is anthropomorphised as he appears to be shouting, pleading George to stop this madness. The intelligence of Uggie becomes apparent as he makes a conscious decision to take action. The camera cuts to Uggie quite literally flying along the pavement. The audience question where he is going, as he runs past people in the street. It is only when Uggie stops at a policeman’s feet that the extreme intelligence of the animal is shown (Fig. 5). Uggie’s barking at the policeman highlights a language barrier between humans and animals. The style of silent film illustrates this further because of the frustration of being unable hear him either when you can see his physical urgency. Hazanavicius superb use of mise-en-scene is very precise, as George lying down after being rescued (Fig. 6), is extremely similar to the image used earlier in George’s own movie (Fig.7). This doubling of images is highly significant as it suggests that Uggie thinks the situation is like a movie again. However, the fact he barked and tried to communicate with George disproves that; it shows Uggie to be more than just an actor dog. He has a higher level of intelligence that makes his friendship and loyalty to George even more endearing to watch.

| Fig.6. Jean Dujardin as George Valentin and Uggie the dog in The Artist | Fig.7. Jean Dujardin as George Valentin and Uggie the dog in The Artist |

The primary use of Uggie in The Artist is to show the companionship between man and his dog. The fact the movie is silent intensifies this bond, because the audience has no verbal clues to draw on. It is this physicality of human/animal relationships that determines Uggie’s necessity to be in the movie. Uggie is George’s only friend and this is a play on silent film, because the dog does not speak to him. George is caught up in his own world of fame and fall from grace, therefore Uggie is perhaps the best companion he could have. The dog represents the quiet, faithful friend, who listens to George: a prominent figure, but not an interfering one, like a human has the potential to be. This demonstrates a true companionship between human and animal. Dujardin as an actor felt this too as he states: ‘Uggie was my shadow and my friend’.[5] These bonds between humans and animals exist outside of the film as well, showing the devotion from Uggie to be real. This purely physical relationship is a catalyst for Uggie being so well trained. The relationship between human and animal is strengthened by the fact Uggie always obeyed George. This is why the scene of saving George from the fire makes the film less about pet-keeping, and a hierarchy of man over beast, but more about true friendship. As an audience, we find this relationship heart-warming.

Animals in silent movies are extremely interesting because they are never given a “voice”. Even the inter-titles of silent films would not accurately depict the tone the dog would be barking in. In animated movies like Ratatouille (2007)and adventure films such as Homeward Bound (1993), animals speak to one another in order to create a dialogue among species that an audience enjoys. Here, Uggie is silenced, and his barks are muted and therefore explores the human/animal relationship without the need for speech.

I believe there is an interesting link between the end of the movie and dogs on film and television today. George’s new-found fame is due to his tap-dancing ability. I find this highly ironic that George must now perform repeated sequences over and over, because of the rise in popularity of dancing dogs today. Television shows such as Britain’s Got Talent have made performing dogs famous, even creating a film, Pudsey: The Movie (2014). Audiences are attracted to physicality of the performance. In The Artist, there has been a subversion of human and animal roles, as to regain his popularity in the talkies era, George must dance.

Pudsey and trainer Ashleigh and Jean Dujardin as George Valentin and Bérénice Bejo as Peppy Miller in The Artist

Further Reading

Friesen, Eric, ‘Music: The Language of The Artist’, Queen’s Quarterly, 119.1 (2012)

Horak, Jan-Christopher, ‘Rin-Tin-Tin in Berlin or American Cinema in Weimar’, Film History, 5.1 (1993), pp. 49-62

Natoli, Joseph, ‘The Artist: Mystification Beyond Artistry’, Senses of Cinema (2012) <http://sensesofcinema.com/2012/feature-articles/the-artist-mystification-beyond-artistry/>

Online video of Rescued by Rover (1905) – <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LlhNxHfyWTU>

Bibliography

Basinger, Jeanine, Silent Stars (New York: Random House Inc, 2012)

The Celeb Factory, ‘The Artist interview: Michel Hazanavicius on Uggie the dog’ YouTube (2012) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CQ-Zio4BIp4> [accessed 28 November 2015]

Filmmaker Magazine, ‘Michel Hazanavicus, The Artist’ <http://filmmakermagazine.com/35047-michel-hazanavicius-the-artist/#.Vl4Jh7TN7zJ> [accessed 26 November 2015]

Robinson, David, Chaplin: His Life and Art, Google Books <https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ovzYAgAAQBAJ&vq> [accessed 28 November 2015]

Uggie, Uggie, the Artist: My Story (London: Harper Collins, 2012)

Filmography

A Dog’s Life. Dir. Charlie Chaplin. First National Pictures Inc, 1918.

Rescued By Rover. Dir. Ceceil Milton Hepworth. American Mutoscope and Biograph Co, 1905.

The Artist. Dir. Michel Hazanavicius. Warner Brothers, 2011.

Where North Begins. Dir. Chester M. Franklin. Warner Brothers,1923.

[1] The Celeb Factory, ‘The Artist interview: Michel Hazanavicius on Uggie the dog’ YouTube (2012) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CQ-Zio4BIp4> [accessed 28 November 2015]

[2]Jeanine Basinger, Silent Stars (New York: Random House Inc, 2012) p. 466.

[3]David Robinson, Chaplin: His Life and Art, Google Books <https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ovzYAgAAQBAJ&vq> [accessed 28 November 2015]

[4]Filmmaker Magazine, ‘Michel Hazanavicius, The Artist’ <http://filmmakermagazine.com/35047-michel-hazanavicius-the-artist/#.Vl4Jh7TN7zJ> [accessed 26 November 2015]

[5]Uggie, Uggie, the Artist: My Story (London: Harper Collins, 2012)