White God (dir. Kornél Mundruczó, 2014) depicts the story of Hagen [Bodie and Luke], a mixed-breed dog, and his relationship with Lili [Zsófia Psotta], a young girl who is sent to live with her emotionally distant father [Sándor Zsótér]. Unwilling to pay the newly implemented ‘mongrel fee’ imposed by the Hungarian government in a desperate attempt to control the stray dog population, Lili’s father ruthlessly abandons Hagen on the roadside, much to Lili’s distress. Whilst Lili searches for Hagen, the film follows his journey through the city, as he is subsequently passed from human to human, all of whom attempt to claim ownership over him in their separate ways. Yet, Hagen refuses to remain submissive to those who abuse, torment and torture him, eventually escaping the dog shelter where he has been taken to be euthanised and leading a canine uprising in which he violently avenges those who have mistreated him.

The generic hybridisation of White God is emphasised by Arlene Landau who describes the film as ‘part myth, part fairy tale, part political fable, and part horror story’. [1] Indeed, reviewer’s attempts to categorise White God within one genre are overwhelmingly inconclusive, with the film described as everything from ‘an urban adventure yarn’ [2] to a ‘Dickensian melodrama’. [3] However, one aspect that the majority of these reviews have in common is that in order to ‘understand’ White God, the film must be read as an allegory. Thus, the film has been considered a comment on class tensions, increasing anti-immigrant sentiment in Europe, and the rise of Jobbik, a nationalist Hungarian political party. Mundruczó himself states: ‘White God is a dog movie, but it’s not about dogs’. [4] Crucially, in the critical discourse surrounding White God, the film gains artistic value only when the animals of the text illuminate something about human society, only when the animal is reduced to metaphor and symbol, ‘ciphers that we fill with our [human] meaning’. [5] The animal must be more than animal.

Nevertheless, in alternate interviews Mundruczó also explains that: ‘I cannot say a specific minority was symbolized by the dogs because they symbolize themselves as dogs’, [6] and an interesting contradiction emerges. If the dog actors are representative of dogs in general outside of the filmic framework, then it is difficult to comprehend how these animals can simultaneously blur the species-boundary to be emblematic of the human ‘other’ also. This movement from the physical to the symbolic is startling subjugating, as the animal body is present only to be masked and concealed, to transmit a message over which it has no control. It is therefore necessary to explore how White God can be interpreted outside of this allegorical structure. To examine what the film can reveal to us regarding inter-species relationships as opposed to simply perpetuating an anthropocentric hierarchy, in which the animal is always the signifier and never the signified. We must make visible the invisible.

Jonathan Burt argues that: ‘the animal image [within film] is a form of rupture in the field of representation.’[7] The animal body cannot be contained by the film itself and the animal cannot be perceived as an actor playing a fictional part. ‘Our attention is constantly drawn beyond the image’[8] as we consider questions regarding the treatment and welfare of the animal throughout the filming process. Yet, White God immediately draws attention to this rupture with its opening credits, which begin not with the traditional ‘No Animals Were Harmed in the Making of This Film’ certification [trademarked by the American Humane Association as an ostensible stamp of approval], but rather with an epigram from Rainer Maria Rilke: ‘everything terrible is something that needs our love’. The film immediately encourages us to see the dog actors as subjects in their own right, as opposed to mere objects which are focalised around concept s of legality and paperwork. Instead of the AHA’s emphasis on animals as a collective, homogeneous group, White God asks us to see the animal as an individual, a distinct body which becomes grouped only through active intention, not passive disregard. This is further emphasised by the film’s closing credits which list ‘és kutya barátainknak’ [literal translation – ‘our dog friends’], followed by the names of all the dogs that appeared in the film. The credits go on to state that all the dogs that starred in the film were adopted by families after production had finished. Through the listing of each separate and distinct dog name, the dog actors are further individualised and granted recognition for their work. ‘Our attention is constantly drawn beyond the image’ as dogs are acknowledged as ‘dog’, and, through the disclosure of the adoption process, each dog once again becomes ‘pet’.

Indeed, regarding inter-species relations, White God asks us to reflect on the distinct categories in which we tend to fix animals. Often this is as rigid types which allow for no progress and evolution. However, throughout White God Hagen shifts between several dog classifications, principally those of pet, meat and beast. His fluid movement between these types destabilises this taxonomy as Hagen becomes both all of them, and none of them, resisting generic archetypes. White God thus presents us with a new way of seeing, as it refuses to allow for just one type of gaze.

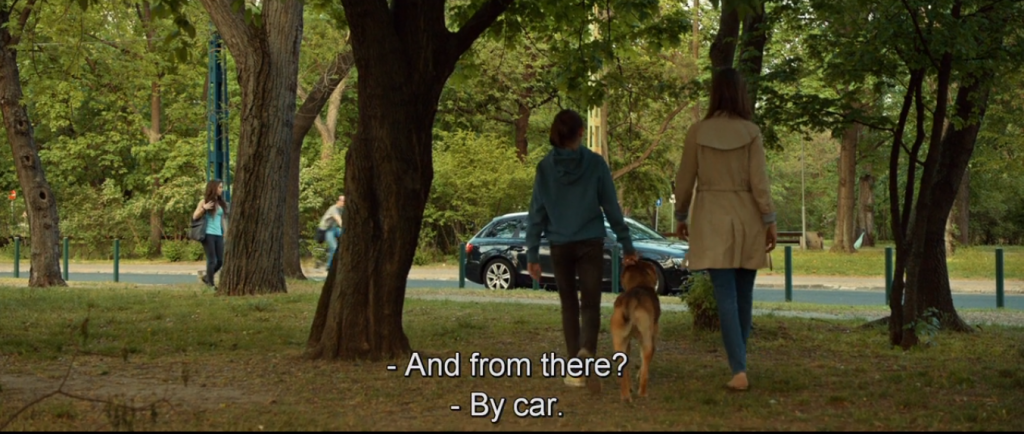

At the beginning of the film, Hagen is a pet. He plays fetch and tugs on a rope with Lili, the shaky and jerky camera movements emphasising the natural ease of this game. The diegetic sound of birdcalls, Lili’s breathlessness and Hagen’s excited whines only underscore this sense of organic bliss. As Lili leaves the park, we become aware that Hagen has no lead or harness and instead Lili firmly grips onto his collar [see figure 3.] to prevent him from running off. He struggles to walk, stumbling over his paws as he tries to slow down his pace to match the rhythm of Lili. Whilst Lili’s control at this point may seem cruel, as she allows no space for Hagen to roam outside of her immediate vicinity, this idea is firmly undermined later in the film. Hagen and Lili escape the stifling claustrophobia of her father’s house to explore the local surroundings. Here, in true nature dotted with rocks and tufts of grass, Hagen is free to move as he wishes, often overtaking Lili. Situated at the top of the hill and looking down onto the city beneath them, the two see a man getting increasingly frustrated as he tries to train his German Shepherd to ‘lie down!’ and ‘sit!’. Lili says to Hagen that she ‘will never do that to you’ and allows Hagen to gently bite and paw at her as he responds to her voice. Lili’s relationship with Hagen as pet thus seems to have two distinct categories: the performative and the authentic. She is subtly aware of societal expectations surrounding pet-keeping and becoming ‘master’ to the dog, to the extent that she can conform to these notions when in public company to demonstrate Hagen’s subordination. Alone and in the natural world together, their relationship becomes more equal. Not only is Lili no longer master, she reveals that she never intended to be.

The indifference with which Lili’s father leaves Hagen at the roadside, surrounded by frantic traffic and beeping cars, illustrates Hagen’s transition from pet to ‘meat’. Whilst Lili’s father does not intend to eat Hagen, the similarity lies in the way in which both Lili’s father and the meat industry treat the animal as a disposable body that is to be consumed [or in this case, taken responsibility of] by another. The rapidity of this incident with its quick cuts and hastily shouted dialogue contrasts greatly to the slow, medium shots that characterise those scenes set in the slaughterhouse where Lili’s father works. Interestingly, it is here that the animal body is handled with care and respect, with workers making sure that they don’t rip the skin before the meat goes on sale to the public. As the slaughterhouse workers look shamefully on at the violence before them [see figure 4], the diegetic sound of blood dripping and the scraping of metal instruments accentuate the abject environment. In White God, it is only when the animal is already dead that we can avert our gaze to one of solemnity and quiet humiliation, compared to the angry and unconcealed force that Hagen is subject to as Lili’s father moulds him into ‘meat’.

It is in the classification as beast that Hagen remains the longest. However, this transformation is not a natural one and is initially forced on Hagen after he is sold to a dog fighting ring. His new owner subsequently injects him with steroids, beats him and chisels his teeth to sharp points. In the ring, as the camera jerks back and forth, Hagen is bloodied and snarling, wrestling with another dog to the sound of human cheers. Staring at his kill, he appears more like the ancestral wolf than the domestic pet of previous [see figure 5].

It is this aesthetic transmutation, combined with the horrific abuse he has received, that signals Hagen’s own metamorphosis into a savage animal, avenging all those who have wronged him. As Hagen and his canine companions race down the streets of Budapest, they look a ferocious and savage pack. In a terrifying turn of events, Hagen’s actions mirror those of the humans at the dog shelter, except now it is his turn to decide who to let live. However, on closer inspection we can see the wagging tails and dog ‘smiles’ that dominate this once visually brutish horde [please see clip 1].

It is in fact the editing techniques which make Hagen and the other dogs appear so vicious. Through a layering of non – diegetic and foley sounds that include both dog snarls and rousing classical music, as well as quick, choppy edits between shots, Mundruczó creates tension and discomfort as we wait for a climax that never quite comes. The use of a widescreen camera that is placed at ground level to show the dogs perspective also ensures a sense of confusion and disorientation as the animals are reduced to a sequence of blurred bodies. This manipulation thus works on a dual level. Not only must the animal ‘act’, but his performance must then be understood from a human perspective. The ‘rupture’ that Burt mentions occurs once again, and we are led to question how these categories of pet, meat and beast relate to our naming and categorisation of dogs in the real world, and how this human way of reading the animal is overwhelmingly contrived.

Oerlemans argues that allegory is ‘the dominant mode’ in which animals enter texts, and it ‘becomes the mode through which they are read’. [9] Yet, White God provides us with the crucial opportunity not only to refuse this reduction of the animal to mere symbol, but instead to see how the lives of animals integrate with our own and to re-consider our relationships with them. Indeed, when we refuse to co-operate with Mundruczó’s initial intensions that are centred around creating anthropocentric meaning, Hagen and the other dogs are given their own agency as they become recognised as subjects both in the film and in the real world. Furthermore, Hagen as subject deconstructs and destabilises the idea of a singular gaze in which to regard the animal. As he moves through several classifications that we use to contain and subsequently read dogs, he blurs the once simple and unambiguous boundaries of understanding and interrogates what it is for us to ‘know’ an animal.

At the end of White God, Lili tries desperately to reason with Hagen, asking him ‘what have you done’ and ordering him to ‘relax!’. As Hagen creeps closer and closer, seemingly poised to attack, she tries a new way of relating, a new form of communication and plays her trumpet until the dogs cease their barking and lie down in her front of her. When her song finishes, Lili too lies down, not subordinate but equal to, and finally, she understands. Gazing into Hagen’s eyes she sees him as pet, meat and beast all at once. She sees him as animal.

[1] Arlene Landau, ‘White God. (2014). Directed and Cowritten by Kornél Mundruczó’, Psychological Perspectives, 59.1 (2016), 149 – 151 https://doi.org/10.1080/00332925.2016.1134228 (p. 149).

[2] ‘’White God’ (‘Feher Isten’): Cannes Review’, The Hollywood Reporter https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/white-god-feher-isten-cannes-705224 [accessed 19th January 2019]

[3] ‘‘White God’: Human abusers feel bite of dog uprising’, The Seattle Times https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/movies/white-god-human-abusers-feel-bite-of-dog-uprising/ [accessed 19th January 2019]

[4] Mundruczó as quoted in ‘Meet the star of art-house favorite ‘White God.’ He’s a good boy.’, The Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/meet-the-star-of-art-house-favorite-white-god-hes-a-good-boy/ [accessed 19th January 2019]

[5] Onno Oerlemans, ‘The Animal in Allegory: From Chaucer to Gray’, ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, 20.2 (2013), 296 – 317 https://doi-org.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/isle/ist020 (p. 300).

[6] Mundruczó as quoted in ‘WHITE GOD Interview: Director Kornél Mundruczó’, The Collider http://collider.com/white-god-kornel-mundruczo-interview/ [accessed 19th January 2018]

[7] Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books, 2002), p. 11.

[8] Ibid, p. 12.

[9] Oerlemans, ‘The Animal in Allegory: From Chaucer to Gray’, p. 299.

Further Reading

Books and Essays:

- Steve Baker – Picturing the Beast: Animals, Identity and Representation, (2001). Baker considers how animal images and iconography throughout history affect how we perceive and look at animals in the real world.

- John Berger – Why Look at Animals?, (2009). A fantastically comprehensible introduction to some of the key issues in animal studies, focusing on the fractured relationship between human and animal that has occurred in an age of consumerism.

- Jacques Derrida – The Animal That Therefore I Am (More to Follow), (2002). Derrida asks what it is that the animal sees when he looks at us, whilst deconstructing the not so clear distinctions between man and animal. This essay can be found at https://www.jstor.org/stable/1344276.

- Akira Lippit – Electric Animal: Toward a Rhetoric of Wildlife, (2000). Lippit explores the animal in relation to modernity, tracking their disappearance from our natural spaces only to be replicated in technological medias.

Films

- Cats & Dogs (dir. Lawrence Guterman, 2001) – children’s comedy which depicts the secret, high-tech war going on between cats and dogs…in our own neighbourhoods! The film is unusual in that it portrays animosity between animal species, instead of animals and humans.

- Wendy and Lucy (dir. Kelly Reichardt, 2008) – drama in which a woman searches for her lost dog after being arrested.

Bibliography

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books, 2002)

Dalton, Stephen, ‘’White God’ (‘Feher Isten’): Cannes Review’, The Hollywood Reporter https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/white-god-feher-isten-cannes-705224 [accessed 19th January 2019]

Dollar, Steve, ‘Meet the star of art-house favorite ‘White God.’ He’s a good boy.’, The Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/meet-the-star-of-art-house-favorite-white-god-hes-a-good-boy/ [accessed 19th January 2019]

Keogh, Tom, ‘‘White God’: Human abusers feel bite of dog uprising’, The Seattle Times https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/movies/white-god-human-abusers-feel-bite-of-dog-uprising/ [accessed 19th January 2019]

Landau, Arlene, ‘White God. (2014). Directed and Cowritten by Kornél Mundruczó’, Psychological Perspectives, 59.1 (2016), 149 – 151 https://doi.org/10.1080/00332925.2016.1134228

Oerlemans, Onno, ‘The Animal in Allegory: From Chaucer to Gray’, ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, 20.2 (2013), 296 – 317 https://doi-org.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/isle/ist020

Roberts, Sheila, ‘WHITE GOD Interview: Director Kornél Mundruczó’, The Collider http://collider.com/white-god-kornel-mundruczo-interview/ [accessed 19th January 2018]

Filmography

White God (dir. Kornél Mundruczó, 2014, Hungary).