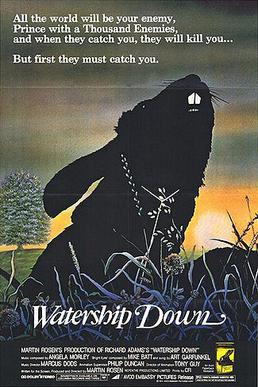

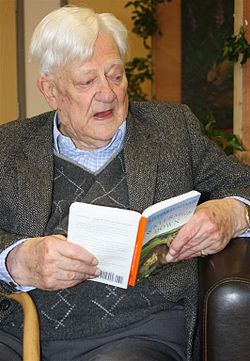

Above left: Film Poster Richard Adams reading Watership Down in 2008

Far from the fluffy, cotton-tailed animals we think rabbits to be, Watership Down (dir. Martin Rosen, 1978) depicts the brutal world of a political and regimented rabbit hierarchy. Chief rabbits dictate from the top of the hierarchy, whilst the military ‘Owsla’ bring down their leader’s iron paw of fascism. Based on the Richard Adams novel Watership Down (1972), the tale follows Hazel (John Hurt) and Fiver (Richard Briers), two brothers who dream of a utopian life without dictatorship. Eccentric Fiver has a vision of an evil peril that faces the warren, but the Chief Rabbit (Ralph Richardson) will not listen to Fiver’s warning because Fiver is a relatively unknown, lesser member of the hierarchical society. The two brothers then lead an escape plot and defy the leadership that chose to ignore them. The journey is thwart with danger from start to finish, from other tyrannical societies to the aforementioned brutal snare traps. Upon reaching their destination, the rabbits realise that their society cannot thrive without the addition of female rabbits to carry on the society. With the help of Kehaar (Zero Mostel), a loud and obnoxious bird they befriend, the rabbits hatch a plan to infiltrate and bring down the totalitarian warren of Efrafar and with it, destroy the tyrannical reign of General Woundwort (Harry Andrews). After the fascists’ defeat, Hazel and Fiver’s dream is realised, creating a happy utopian life for all of the rabbits in Hazel’s warren.

Animation has a contested status as a genre, and Watership Down includes a hybrid of the genres of family film, action, moments of horror and political subtext. Though animation usually targets an audience of children, Watership Down also attracts an adult audience through the darker political plot. It is the political subtext and the violence within the film that makes Watership Down stand out amongst other animated animal films. Paul Wells writes in The Animal Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons and Culture that ‘animation could embrace radical perspectives and challenge reactionary views’. Animal characters can confront the political problems of our own society, like hierarchy, without causing the viewer to intentionally avoid the issue. Many viewers would recoil from such messages if presented by a human character due to it being far too close to the dark truth about ourselves. Thus, the use of animals to challenge our own society creates a space in which to explore these issues without causing the viewer to avoid the hideous truth. Using the entertaining story of the rabbits, hierarchy is shown to be a negative force within the film world and within our own world. Watership Down brings forth an allegory about the hierarchies that exist in human society, showing the viewer that tyranny does not help a society to thrive. However, the film also explores literal problems that hierarchy cause within the human world, with snare traps being a point of contention for animal welfare activists like Richard Adams. Therefore, the animation form of Watership Down uses and breaks our perception of rabbits as fluffy and harmless to present a far more intriguing and hard-hitting antifascist message which can be applied to our own society.[1] The film aims to make the audience review their own complicity as these issues happen in our own society.

The initial escape scene introduces the idea of tyranny within rabbit warrens, as the Chief Rabbit (Ralph Richardson) will not take Fiver’s warning into account because he is not high up in the social hierarchy. It is the double-focused form of animated films that allows Watership Down to challenge the hierarchies that are allegorical of our own society. Loud, trumpeting music clangs in the background of the scene as the dissenters try to escape, creating a feeling of panic within the viewer. The rapid jump cuts between the group and the pursuing Owsla emphasise this panic and fear, making clear that the two groups are in opposition: the oppressed escapees and the oppressors in pursuit. The Owsla are drawn with hostile expressions, accentuating that they are the villains. The drawn nature of animation allows the film to stylise the characters to emphasise who the viewer should ally with, the angry Owsla and ugly Chief Rabbits being presented as unattractive so that children and adults naturally align against them. However, Owsla member Bigwig (Michael Graham Cox) joins the dissenters, which suggests that it is not the Owsla personally who are the problem. Instead, the problem is within the regimented system itself which will not allow for individuality or autonomy. The tyrant Chief Rabbit will not listen to suggestions made by others, but he also will not allow them to leave his society because he wants total control over his subjects. The viewer is warned of the totalitarian, restrictive nature of hierarchical structures from the very first warren that is presented, making it clear that hierarchy is a major issue within the film.

Bigwig caught in a snare

The film also shows that humans have created a hierarchy between us and animals, whereby humans are at the top of the pyramid and animals are below on various levels. The gruesome snare scene is another argument against hierarchical structures, as we are shown the bloodshed that comes from this human-over-animal hierarchy. The BBFC report states that ‘Animation removes the realistic gory horror in the occasional scenes of violence and bloodshed’, and as this is animation, the filmmakers avoid animal cruelty and can make the scene as harrowing and bloody as possible.[2] Bigwig is caught in a snare and struggles to remain alive whilst the others try to save his life. Throughout the scene, red blood is drawn spreading around his mouth as he lies on the grass. The gory image of flies surrounding the bloody, corpse-like rabbit is one of horror and seeks to shock the viewer into realising the impact that humans have on other creatures. By using the audience’s sentimental attachment to the individual Bigwig, the film aids welfare campaigns against the use of brutal snare traps against wildlife. Unlike in the real world, the group are able to save Bigwig by working as a team. Adults watching the film would be aware that this is pure fallacy, as rabbits have no organised groups that can fight for their own individual lives. Therefore, the film emphasises that we must be the protector of these creatures by campaigning against the cruelty. However, staying within the fictional world, the film’s narrative demonstrates that every member of society is important, which is not something a hierarchy would acknowledge. A bonded, equal society is shown to prevail over hierarchy in the saving of Bigwig, as the rabbits conquer the human endeavour to kill them and therefore conquer the human-over-animal power structure.

The inequality within a hierarchy is emphasised again within Efrafar. Those who have lived in the society longest do not get privilege to move up the hierarchy, yet newcomer Bigwig is given power due to his previous officer position and fighting skills. Subjects have a mark clawed into their side which states when they are allowed above ground, and those who try to leave Efrafar are beaten and their ears ripped. Tyrant General Woundwort’s regime is arguably the most severe and demonstrates the dangers of fascism gaining power, as the subjects are not allowed to make the most basic decisions for themselves and have no way of moving up in society. A tyrant’s position at the top of the hierarchy is achieved through having followers to do his bidding. Woundwort has unrealistic assertions about the amount of power he possesses on his own. He is defeated because he believes he has more power than the dog trying to kill him. A tyrant’s power is shown to be dependent upon the strength of a mass of followers and the inequality within hierarchy can be broken once these followers have been removed.

Bigwig’s infiltration and the escape demonstrate that by working together, tyranny can be fought and beaten. However, the utopia is not achieved by escaping the tyrannical society, as General Woundwort and his Owsla find the group’s new home and try to regain power over all those who escaped. General Woundwort is at the top of the hierarchy and knows an equal society would not serve his totalitarian, selfish needs. Hazel’s diplomatic terms that ‘we should be together, a joining of free, independent warrens’, are ignored because Woundwort cannot see how such a society can benefit him, as his needs are his only priority, demonstrating that tyranny cannot be reasoned with. Woundwort believes that the strongest, most powerful member of a warren should be the leader because they can assert power over others. Hazel’s leadership is in opposition to this view, and it surprises Woundwort to find out that Bigwig is not the leader. Bigwig states that ‘my Chief’s told me to defend this run’ and Woundwort replies ‘your Chief?’. Hazel is the leader of the group because he is able to put the needs of the group before his own individual needs, not because he is the most powerful and domineering member. Hazel’s leadership is shown to triumph over Woundwort’s fascism, presenting that fascism can be beaten by a society of equality.

Though the group meets with opposing forces, they fight fascism through to the end of the film. As they win their utopian society, the viewer is shown that fascism can be fought and beaten. Through the anthropomorphic use of rabbits in the place of humans, we are shown the dangers of tyranny in a way that is entertaining, preventing the tale from becoming too political whilst still delivering an important message. The animated form of the film means that violence can be shown without harming animals to achieve this. The animators are therefore able to emphasise the more gruesome parts of the film, giving them more visual power. The snare scene is effective because of the increasing amount of blood that begins to seep around Bigwig’s mouth. The horror of this causes the viewer to think about the harm that such man-made contraptions cause on animals, as most viewers would never have seen an animal caught in a snare. This aids the literal political message of campaigns against such devices, as the viewer is shown that only they can help protect the animals since the animals themselves have no such power. The violence of Efrafar is necessary to prevent the reality of fascist societies, which punish anyone who dares to challenge the tyrannical leader. This parallels the reality of real, human fascist regimes and warns the viewer that hierarchy within society can cause this severity of power structure.

Through unpicking the hierarchical structures within Watership Down, I can draw comparisons to British animations Animal Farm (dir. Joy Batchelor and John Halas, 1955) and Chicken Run (dir. Peter Lord and Nick Park, 2000) through the way that all three films depict oppressive societies that cause the oppressed animals to attempt to escape the tyranny. Animal Farm and Chicken Run revolve around the oppression within a farm, whereby humans are at the top of the hierarchy and completely in control of the animals within that hierarchy. Chicken Run includes an escape plot and the chickens plan to build a utopian society free from human intervention, much like Watership Down. In contrast, Animal Farm demonstrates the real difficulties in maintaining a completely equal society, as hierarchy is shown to form once again but with a different leader at the top of the social structure. However, Watership Down takes place completely in the wild, where humans do not have control over the animals but nevertheless still disrupt the lives of these wild creatures. These films demonstrate that the use of animated animals allows political messages to be delivered in a more entertaining way that captures the audience’s attention. The novelty of the animals representing human issues prevents the viewer from simply switching off.

Filmography

Animal Farm, Dir. Joy Batchelor and John Halas, Distributors Corporation of America (United Kingdom, 1954)

Chicken Run, Dir. Peter Lord and Nick Park, DreamWorks Pictures and Pathé (United Kingdom, 2000)

Watership Down, Dir. Martin Rosen, CIC (United Kingdom, 1978)

Bibliography (Primary Sources)

BBFC Examiners Report 15th February 1978, <https://www.bbfc.co.uk/sites/default/files/attachments/Watership-Down-report.pdf> [last accessed 26 November 2014]

Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture (Rutgers University Press, 2009)

Further Reading (Secondary Sources)

Anderson, Celia Catlett, ‘Troy, Carthage, and Watership Down’, Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, Spring 8.1 (1983) <https://muse.jhu.edu.eresources.shef.ac.uk/journals/childrens_literature_association_quarterly/v008/8.1.anderson.pdf> [accessed 26 November 2014]

Battista, Chrissie, ‘Ecofantasy and Animal Dystopia in Richard Adams’ Watership Down’, in Environmentalism in the Realm of Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature (Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars, 2012), pp.157-167

BBFC Examiners Report 15th February 1978, <https://www.bbfc.co.uk/sites/default/files/attachments/Watership-Down-report.pdf> [last accessed 26 November 2014]

Tyler, Tom, ‘If Horses Had Hands…’, Society & Animals, 11.3 (2003) <https://www.cyberchimp.co.uk/research/horseshands.htm> [accessed 26 November 2014

Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture (Rutgers University Press, 2009)

[1] Paul Wells, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture (Rutgers University Press, 2009), p.65

[2] BBFC Examiners Report 15th February 1978, <https://www.bbfc.co.uk/sites/default/files/attachments/Watership-Down-report.pdf> [last accessed 26 November 2014]