Do you want a second chance, Cole?”

In other words – Do you want your body experimented upon to benefit our research again, Cole?

The film cuts to a scene where Cole is injected and pinned to the time machine… or rather, torture machine. Cole never gets to answer the question – he has no choice.

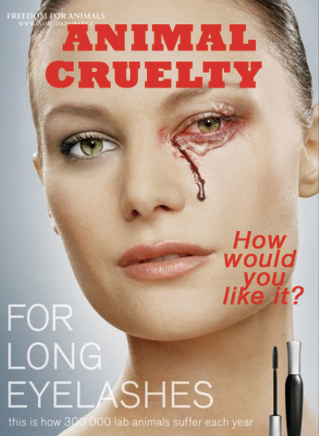

The survivors’ ‘escape’ from the deadly virus is “a giant medical prison, where scientists rule . . . where shaven, bar-coded, and caged inmates are selected to ‘volunteer’ for lethal experiments.”[1] The survivors are animals – laboratory animals.

When animals get injected and pinned to the torture machine, like Cole, they can’t answer a question – they have no choice.

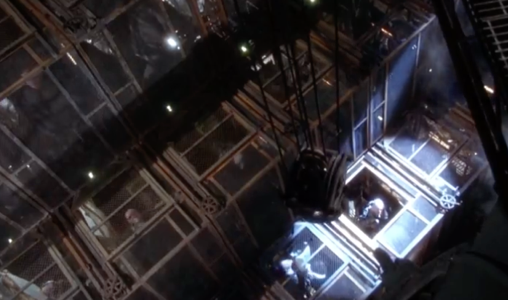

After the audience is introduced to Cole and his fellow cellmate on an individual and personal level – the camera zooms out to introduce the audience to the caged beings in their entirety. Their portrayal develops into a non-individualised species – whooping and rattling in their cages. They are no longer presented as caged laboratory humans – they are now caged laboratory animals. Therefore, Terry Gilliam’s animalised and brutalised human protagonist unveils the immorality of the treatment towards laboratory animals. The audience can empathise with Cole better than an animal because we are a narcissistic race. We search for other humans suffering so that we can pity our own suffering – to find catharsis – for reassurance that we are not alone. It is the human form that aids our ability to see the other sufferer as a reflection of ourselves. Therefore, Cole – the human protagonist – allows us to infer the treatment towards him as disturbing and cruel.

Surprisingly, Gilliam doesn’t evoke the audience’s empathy with Cole by using camera shots which place us in Cole’s perspective. Instead, audience empathy is achieved through point of view shots which place us in the camera’s position, moving around Cole in the metal chair. We are the ones analysing him; trapping him. Despite the presentation of a human victim evoking our empathy, the camera shots force us into the perspective of the victimisers. We can only watch this scene in the shoes of the scientists. Yet as fellow human beings, we have to pay the emotional consequences of witnessing Cole’s suffering.

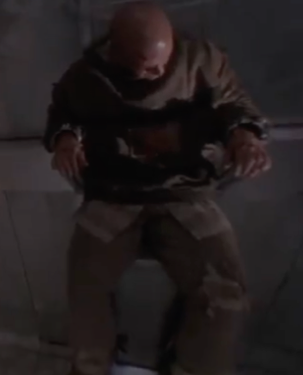

In the following scene, industrial medical materials are layered between Cole and the camera, increasing the distance between him and the audience. The point of view shots place us as the scientists who strap and clip Cole to the time machine. We (the scientists) wear identical uniforms which conceal our identities – our guilt is hidden behind the uniform; behind the TV screens. Cole, however, lies naked, trapped between the wires and plastic – he is exposed and vulnerable. The scientists’ faces are never captured in the same shots as Coles’ – highlighting the scientists’ emotional distance from him as a person. Moreover, from the point of view shots of the scientists, Cole’s body is introduced in fragments…

First, they inject his arm…

Then, they clip his neck to the machine…

The camera shots only show the audience the parts of Cole which are being used for the scientific study – not one whole being with an identity. This creates a representation of how animal testers may perceive animals. The human subject illuminates the immorality of this perception to the audience.

The film exposes the cruelty of animal testing through placing the audience into the testers’ perspective and providing a subject who evokes empathy – “The ability to understand and share the feelings of another”[2]. We understand no species better than our own. Likewise, we share our feelings most similarly with beings of our own species. Therefore, as humans, we are capable of projecting the horror of torture upon ourselves most effortlessly when it is applied to another human being. We do not want to be tortured, nor do we want to be the torturer. The only conclusion Gilliam makes available to us is – experimenting on another living being is wrong.

The film shows the characters that “the future is history”. The film shows the audience that without this crucial, though distressing reality check – history is the future.

[1] David Lashmet, ‘“The Future is History”: “12 Monkeys” and the Origin of AIDS’, Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, 33.4 (2000) 55-72, (p. 58).

[2] “Empathy | Definition Of Empathy In English By Oxford Dictionaries”, Oxford Dictionaries | English, 2018 <https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/empathy>

Bibliography

Lashmet, D. (2000). “The Future is History”: “12 Monkeys” and the Origin of AIDS. Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, 33(4), pp.55-72.

“Empathy | Definition Of Empathy In English By Oxford Dictionaries”, Oxford Dictionaries | English, 2018 <https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/empathy> [Accessed 12 December 2018]