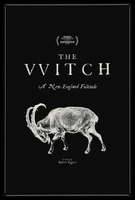

Robert Eggers’s 2015 independent horror film The Witch encounters human-animal relations in reference to a manmade issue – religion and the occult. I argue that such a representation of humans living alongside animals in the context of a restricted, puritanical environment of their own making exists because of how the characters decide to build their own isolation. Otherness encompasses not only the animals that are controlled by the human characters (as in, ‘otherness of species’) but how the animals compare to the victims of the family’s subjugation, such as the teenage protagonist Thomasin.

The film opens bleakly, with the family patriarch, William, demanding, ‘what went we out into the wilderness to find?’ This initially could be seen only as a religious lament, a post-lapsarian family wondering how and why they would forsake paradise. Within the lens of animal-based analysis, the line is a question that cannot be answered. The ‘wilderness’ to William could encapsulate anything that he is unfamiliar with, or contradictory to the kind of life that the family have set up for themselves. Animals inhabit the wilderness, feed off it, and create new life within it. In the case of this Puritan family, to encounter animal otherness is to bring about their own misery and undoing.

Religiously, the family had already been isolating themselves. Their fear and paranoia parallels how they have cut themselves off from the rest of the humans that were part of this constructed ‘civilisation’, interestingly enough, on a plantation where the main source of life comes from the ground. The noises that they hear as they leave their village are distinctly that of domesticated or ‘useful’ animals, such as roosters and sheep. The animals are clearly separate, subject to the whims of the humans that entrap them. The only time that animals are seen before the family’s move away from the plantation is when they are fenced in, ridden or dead in the hands of some trader. It is without question that it is assumed that anything remotely ‘other’ to the Puritan family must be an enemy, that beyond the farm where they live are creatures seeking to harm them. Their choice of livelihood, a farm, is fascinating too, seeking some form of control over the animal, other world. To place the fence around the animals living there (including the humans) is testament to such paranoia. If the animals cannot die immediately because they are of use, they must be contained. If the animals are not contained, they will attack vengefully because of a collective knowledge of how humans have treated their brethren.

Despite their worst fears, the family become part of the natural landscape themselves, with the colourless cinematography making them indistinguishable from the animals that surround them, such as the long shot where they leave the plantation they previously occupied on a horse-drawn cart. They are surrounded by grey bleakness, and are static in comparison to the lively animals, such as Black Phillip the goat rearing onto his hind legs and the hare that William and Caleb see bolting through the otherwise quiet woodlands when they are hunting. Converging with the animal other, the twin children Mercy and Jonas even lose their power of speech at some points in the film. Instead of speaking to one another coherently, they communicate by mimicking the bleats of the goat and mewling at one another. Humans’ supposed natural advantage, the ability to communicate through language, is made completely useless to them, because not only do the human characters fail to communicate and find support with one another, their muttered prayers and hymns do nothing to evidence a listening God constructed by humans. Mercy and Jonas rarely speak with human language to communicate except when they are confident that Black Phillip understands them, and when they speak to him, it is not so much a master requesting an answer from a servant, but a child requesting answers from a god. The children deify Black Phillip for his otherness and seeming exoticism, sure that if they speak directly into his ears with perfect diction, he will be able to give them something in return. Black Phillip does gain the ability of human speech; however, this is not actually depicted in the film. Instead, it could be argued that Thomasin has surrendered to her own animal otherness and can now understand what other humans only hear as incomprehensible bleating.

What seems shocking to the family and the filmic audience is the first loss of the baby Samuel to the witch (although a wolf is repeatedly made scapegoat and hunted for what it has not done). It is unusual to acknowledge in a rational world that babies can be used as sacrifice for an occult ritual, or that anyone would consider a human baby as a piece of meat to be farmed and consumed. And yet, this uncomfortable feature in The Witch puts humans and animals on equal footing in terms of natural power, and the previously sacrosanct child is ground down to a paste. As the witch has no qualms eating and consuming the baby Samuel, Thomasin recognizes the tragedy of an eggshell breaking with an unhatched chick inside. What is feared is how the characters must face their own basic mortality as an animal before it is even hatched. Despite what we as humans assume is greater intelligence, ultimately the consumption of humans in addition to animals gives weight to the argument that we are no better and no less like breathing meat. Throughout the film, the witch’s appearances see her consuming human flesh – the most memorable instance being the baby Samuel’s – and then later, the nanny goat Flora, under Thomasin’s guidance, produces blood when milked, which the witch drinks. Corporeally, the ‘otherness’ of the witch forces the human characters to see themselves as no different from other consumable creatures. For Thomasin’s last depicted act to be the slaughter of her own mother is for her character to submit to the temporary nature of flesh and see no tragedy in either human or animal blood being spilt.

Animals are only ever seen by the family leaders, William and Katherine, as ‘other’ to their existence, something primal that they should fear as involved with the occult. Alan Bernard McGill points out in his essay, ‘The Witch, the Goat and the Devil’ that it is building myth around otherness to inspire fear that can make trouble more so than the otherness itself. He argues that, ‘The demonization of the Other can unleash murderous potential’ (p.411) . The witch is representative of something animal, in cohabitation with nature instead of on its behalf. All the animals behave on her behalf instead of her acting on theirs – she gives over to their power. I recognise that the witch in the film is not so much giving over all of her power as sharing a mutually beneficial power dynamic with the animals that are embodied to communicate with her. The concept of a witch’s familiar has often been argued as a symbol of female empowerment, and the film The Witch seemingly emphasises this sentiment. Although the witch is frightening, her presence is one of authority and power, and the group of witches levitating around a fire at the end of the film is shot from far away, so that their bodies are a blur. Because they are unknown beings and acting in their own space, they cannot be objectified or used, similar to animals in their natural habitats or as of yet undiscovered.

The only character so heavily gendered that she is forced into unknowing oppression is Thomasin, who acts as the ‘other’ infiltrating the human construction. She has the first ‘signs of womanhood’ that make her subject to human men as animals are subject, as her mother notes to her horror. No longer is she to be as sacred as the treasured baby Samuel, untouched and untouchable. She is there to be of use, and at these first signs has her mother demand that she is essentially sold to another family for their purposes. She is accepted by the witch, who is both symbolised and represented by the hare, as the animal kind of ‘other’. Thomasin struggles to conform to the trappings of a human life where the subjugation of animals reflects her own subjugation to expectations of behaviour, religious life and familial pressures. She feels most at comfort when in the frame of the barn, not petting the nanny goat, but seemingly communing with it. She and Black Phillip, the family’s other goat, are both made scapegoat for the misfortunes that befall them. Arguably, the final scene of the film where Thomasin dances with the witches without human-made clothing is when she is most at her ease.