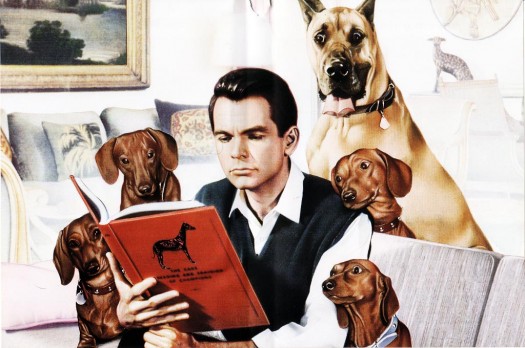

The Ugly Dachshund (1966), adapted from the 1938 novel by Gladys Bonwyn Stern, begins as Mark Garrison (Dean Jones) frantically prepares to drive to the hospital. This tricks us in to thinking that his wife, Fran Garrison (Suzanne Pleshette), is going to give birth when in fact they are taking their Dachshund Danke to the animal hospital to have puppies. When Mark returns the next day to retrieve Danke and the three puppies, the family vet, Dr. Pruitt (Charles Ruggles) persuades Mark to take a Great Dane pup (Brutus) home with him to be weaned by Danke. Mark leads Fran to believe that the puppy is a male Dachshund, but as Brutus gets older it becomes obvious that he is a totally different breed of dog — a very large breed at that! Fran then decisively returns the dog to the vets as he has, by then, been weaned by Danke. Mark then becomes exceedingly unhappy, so she regrettably presents Brutus to Mark as a birthday present (figure 1). Following this, the dachshunds collectively destroy the Garrison’s perfect home, but Fran places all the blame on Brutus. The chaos created by the dogs sheds light on the tensions that emerge in Mark and Fran’s relationship. The films resolution occurs when Mark secretly trains Brutus for a dog show, and he wins the ‘best of breed’ ribbon. Fran then rewards Mark by allowing Brutus to remain in the household.

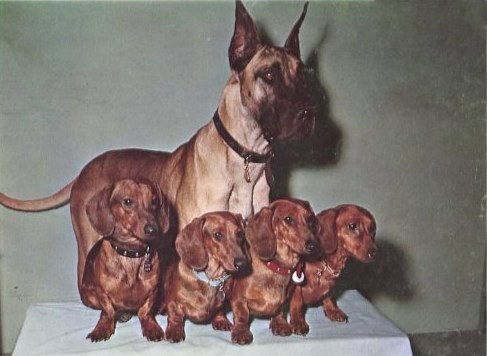

Walt Disney’s The Ugly Dachshund, was one of the many live action films to be released in the 1960s. The romantic comedy-come-family film is delightfully energetic; suitable for adults, children and even your pet dogs will be drawn in by the barking and frolicking puppies. Thecomedy is derived from the way the Garrisons’ relationship revolves entirely around their dogs. The small dogs wreak havoc throughout the house, fuelling Fran’s frustrations. The adorably small, female Dachshunds are cleverly trained to create the chaos, leaving poor Brutus to bear the brunt of Fran’s wrath, as she considers him to be a “clumsy” large male. The use of arch humour in the film will have animal lovers and dog owners giggling in their seats. Like many family films ‘the animal is an explicit focus of attention (1). The film focuses our attention on five dogs and is visually appealing due to the contrast of the small Dachshund to the large Dane (figure 2). It is especially playful when accelerated motion is employed, as it makes the dogs’ movements faster and more comical. Burt considers that: ‘there are also films that have led to a surge in sales of featured animals…101 Dalmatians acted as an advertisement for this visually striking breed of dogs’ (2). These sorts of family films do not only appeal to the audiences sensibilities, but they also commodify the dogs that are featured. It is evident that they have been rigorously trained and show tremendous skill, which would undoubtably appeal to potential dog owners.

In Lady and the Tramp, Tramp says that Lady leads a “life on a leash” as she is domesticated, contained within the household and controlled by her owners. The Ugly Dachshund explores Fran’s desire for Mark and Brutus to live “life on a leash,” but the fundamental problem is that neither of them can be read as domesticated because of their gender, which is problematised by the inversion of gender roles. Nadel suggests the Lady and the Tramp can be read as ‘articulating the role of female sexuality by simultaneously valorising and domesticating male sexuality [so] the issue of domestic security is identified as a gender problem’ (3). At the beginning of The Ugly Dachshund, Mark is flustered and unable to compose himself meaning that he gets the telephone stuck in his jumper sleeve. Later on in the film, Brutus gets tangled in lots of wool that the Dachshunds have trailed around everything in the room. When Mark attempts to rectify the mess, he ends up smashing Fran’s expensive vase. These instance’s of domestic incapacity are employed for comedic effect, but also extend to the issue of domestic security in the absence of Mark leading a conventional working life.

Not only does Fran give Brutus back to Dr. Pruitt against Mark’s will, she also requests that Brutus sleep in the garden when he returns. When Mark takes him outside, he too gets locked out, showing that the male domain is external rather than internal. Even Mark’s art studio is outside in the garden. This demonstrates that Fran’s sexuality and the fact that she is in socio-financial control entitles her to choose whether or not Brutus and Mark remain in the household, showing that both of them lack domestic security. In true Hollywood style, the film ends in resolution with Mark and Fran unified in a frontal medium shot, which cuts to a point of view shot of Brutus and the Dachshunds sleeping indoors together. Fran announces that the day has ended far better than it has begun. This is because Mark and Brutus have won a blue ribbon for ‘best of breed,’ showing that they have become domesticated. Fran’s wishes of owning a champion dog are fulfilled, and the ribbon represents that Mark and Brutus are tamed and constrained. Mark proceeds to claim that: “females always make the difference,” showing that he is conscious that Fran has determined what an audience may deem to be domestic bliss.

The audience humour Fran when she says: “I don’t want to have any more problems about the dogs” as she allows the dogs have autonomy within her and Mark’s relationship. The dogs are substitutes for children, exemplified by moments such as when Mark asks Fran to pose for his painting of a mother and baby using her dachshund, Danke. The film’s advertisement suggests ‘It’s a daffy disaster…when a Great Dane turns a Happy Household into a marital doghouse,’ showing that the films appeal is directly associated with the amount of control the dogs have over the fate of their marriage. Burt suggests that:

‘The roles the animals often play, particularly in fiction films, involve notions of agency and in that sense, the animal, even if unintentionally, comes to determine it’s effects as much as they are determined by the position it is placed in by humans.’ (4)

Fran says that Brutus is “a sweet, clumsy klutz, not proud like a Dane.” Her expectation is that Brutus (and similarly Mark) must be proud (vis-à-vis being composed and in control of themselves) in order to be domesticated. However, the reason that Brutus is undomesticated is because he was placed in a position (by Mark) to be reared by Danke alongside three female Dachshunds in order to fulfil his desire of having a “real dog”. The problem is that Brutus thinks he is a Dachshund (a quarter of the size that he actually is). His mistaken identity is comical as he tries to perform as a domesticated Dachshund, stooping low and attempting to get under and over things. Rather than displaying a “solidarity and strength,” as a male ally, Brutus’ Dachshund-like behaviour jeopardises Mark’s domestic security because in The Ugly Dachshund dogs are extensions of their owners’ character. In the dog show sequence, the visual exaggeration of dogs resembling their owners is toyed with in order to reinstate this idea (figure 4). In this sense, the Dachshunds (“the girls”) intwined with Fran’s character, able to hide their faults as they are small, sociable females. Brutus and Mark are also inseparable characters as they are always to blame for the mishaps because of their asocial nature, foreign to the domesticated females. The intertwining of dog and owner is visually comical, but socially problematic as gender is represented as a determinant in terms whether the individual is accepted within the confines of their own home.

In The Ugly Dachshund the male is presented as undomesticated and is consequently not fully accepted in the home, whereas the female is empowered solely because of her gender and aesthetic. Fran is ultimately able to control Mark and Brutus, forcing them to sacrifice their own individual happiness for the happiness of the family (in order words for “the girls”). Nonetheless, the films’ visual appeal lies within its ability to delight the audience by contrasting the behaviour and size of the Great Dane with the Dachshund. It is significant that the blame for the destruction is gendered, meaning that the males are emasculated; forcing them out of the safe domestic space, into the external world. The films gendered representation of the dogs is for comedic effect, but allows the audience to consider the social consequences of this way of life.

The Ugly Dachshund bears resemblance to Lady in the Tramp (1955). Like the Dachshunds, the Spaniel Lady is small and feminine and seen as the perfect pet. It is through a process of acceptance that Brutus, Mark and the Tramp (a mongrel) become domesticated. Jim Dear longs for a baby boy, and Mark longs for a male dog as a way of escaping from the female domain. The comedic elements also chime with Beethoven (1992) as George does not want a large cumbersome St. Bernard in his perfect home. The comedy emerges from Beethoven’s behaviour as he is a large breed of dog like Brutus. This is also a tale of acceptance, as George accepts that his family love their dog despite his size and naughty behaviour.

(1) Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books ltd, 2002), p. 189.

(2) Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books ltd, 2002), p. 189.

(3) Alanda Nadel, Containment Culture: American Narratives, Postmodernism and the Atomic Age (London, Duke University Press, 1995), pp. 117-125.

(4) Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books ltd, 2002), p. 30.

Videography

The Ugly Dachshund, Norman Toker, Walt Disney, 1966.

The Lady and The Tramp. Dir. Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson, Hamilton Luske. Walt Disney. 1955

Beethoven, Brian Levant, Universal Pictures, 1992

101 Dalmations, Dir. Clyde Geronimi, Hamilton Luske, Wolfgang Reitherman. Walt Disney, 1961

Bibliography

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books ltd, 2002)

Nadel, Alanda, Containment Culture: American Narratives, Postmodernism and the Atomic Age (London, Duke University Press, 1995)

Further Reading/Viewing:

The Disney Films ‘The Ugly Dachshund 1966’, <https://thedisneyfilms.blogspot.co.uk/2011/10/ugly-dachshund-1966.html> [accessed 4 January 2015]

The Ugly Dachshund Trailer, ‘Great Dane 1966’, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FLQMQYx4y4s> [accessed 4 January 2015]

The Ugly Dachshund, ‘Destructive Weenie Dogs’, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sy3Ei0dnNqE> [accessed 4 January 2015]