Synopsis

The Prestige (2006) is a film directed by Christopher Nolan and based upon an adaption of Christopher Priest’s 1995 novel. The film is set in twentieth century London and follows the lives of two rival magicians, Robert Angier (Hugh Jackman) and Alfred Borden (Christian Bale) and their competing struggle to claim ownership of the most notorious illusion, known as the ‘Transported Man’. This conflict descends into escalating acts of violence and revenge and Nolan uses the symbol of the canary bird to exemplify several key themes. The opening scene depicts the loss of the bird through a magic trick, a loss which is crucial to the understanding of the film and it is this moreover, which deconstructs traditional ideas surrounding the innocence of ‘magic’. Instead, the outcome of this one magic trick is a symbol for the indelible corruption of society and is particularly prevalent through the series of depictions of violence exemplified in the film. In addition, the canary bird metaphorises the entrapment surrounding the majority of characters in the film but most particularly in the case of Sarah Borden who chooses death as a bid to regain her autonomy, in a very evocative scene which irrevocably associates her with the birds. Finally, the undercurrent of fear surrounding human degeneration and scientific advancement is portrayed through the manipulation of the natural, and the ability to condemn an animal to death with a refusal to allow it human emotions on a par with humans.

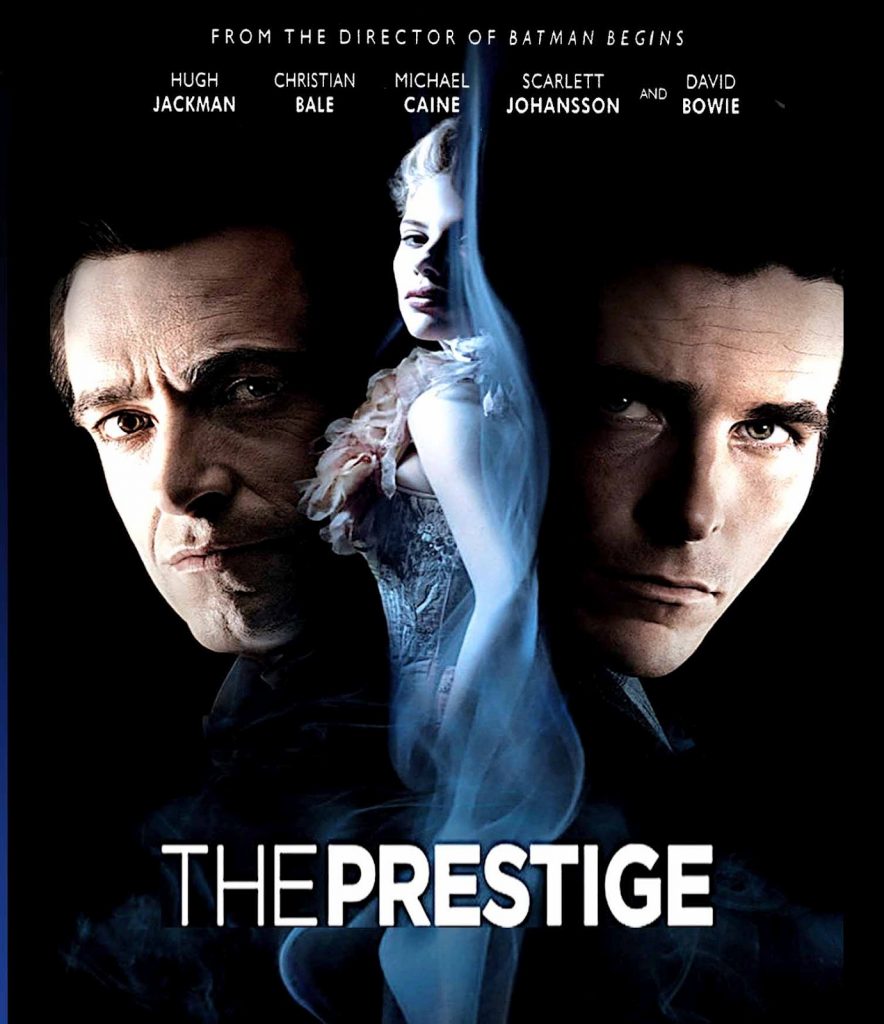

(Film cover for The Prestige)

Genre

The Prestige does not represent one particular generic focus, but instead encompasses elements of drama, mystery and suspense thriller genres. The drama genre is characterised by its ability to identify with real life issues and concerns, which is certainly true in The Prestige as paralysing grief, alcoholism and suicide are all explored. Yet, the film also complies with many of the expectations of mystery, exemplified through the film’s interaction with the imaginative and fanciful uses of magic, which carries the film in a far more dynamic direction. The sub-genre of the suspense thriller is perhaps the most essential generic contribution to the plot, as it is used to enhance a feeling of anticipation through the film’s self-conscious orchestration to replicate the theatrical structure of an illusion.

Animal presences in the film

The opening scene of the film immediately interacts with the conventions of the suspense genre as it presents a set of identical top hats, a deliberate choice by Nolan to allow the audience to reconnect with traditional images of ‘magic’. Nolan immediately aims to reconfigure our previous notions surrounding magic, so instead of representing childhood memories of innocence, it alternatively opens up possibilities for corruption and decadence. Therefore, the initial scene deliberately plays on societal expectations that the dark void of a top hat is irrevocably associated with the positive ascent of a pure white dove. The contrast between the black and white is visually suggestive of the change from the darkness of disbelief to the innocence of conviction in magic. Yet, Nolan deliberately subverts our expectation of magic, the hat and the bird are consciously disconnected and the purity of the white dove is undermined by instead presenting the yellow feathers of a canary bird. This dramatic colour transformation demonstrates a symbolic link between the birds’ feathers and the taint of sin, with each character in the film showing a capability towards a dark corrupting inner self.

(Opening scene in the film)

In addition, there is a clear contrast between the freedom of the hats’ position in the film, often displayed in natural settings, which is a surreal image and is used effectively in key moments of the film to signify when true ‘magic’ had been performed or, in actuality, science. Scientific advancement is portrayed to be an uncontrollable and potentially dangerous aspect of modern society, with its ability to transform the before only magical possibilities into reality. Yet, crucially, the canary birds are irrevocably removed from their natural environment, lingering instead among industrialised locations and inside man-made cages. Birds are a traditional image of freedom, as by their very nature they are often far out of reach of human handling, however, Nolan associates the birds continually with entrapment. In addition, the use of the canary to demonstrate the successful construction of a magic trick rather denigrates the bird to a mere prop in human entertainment. Moreover, as the voiceover insists ‘you don’t really want to know’, which sheds a rather disconcerting light on the human desire to be fooled and displays a troubling ability to conceal the parts of ourselves that we would rather not acknowledge. However, crucially, the film does not revel in the success of magic and promote this artistry, instead, it pushes the audience to ask for the truth behind the illusion and whether the price of a life is worth this fleeting moment of deception.

Furthermore, the film suggests that on some level the audience is aware that the bird has not survived this magic trick, portrayed through Sarah’s nephew crying ‘but where’s his brother?’ instead of laughing along with his peers. His insight is manifestly important as we see humankind’s reluctance to acknowledge the violence needed to entertain and create this trick, caring only that on the surface, some form of bird has returned. Moreover, the idea of a ‘brother’ is crucial, as the film takes a cyclical structure, beginning and ending in this room and with this trick, representing that the cost of creating this legendary performance was the ultimate sacrifice, the death of one of the Borden twins. In addition, Angier sentences one of his duplicated selves to drowning in a water filled tank, yet another link to the traditional forms of magic tricks and profoundly effective at again removing the original innocence behind it. Therefore, the death of the bird, the death of Angier’s duplications and the death of one of the Borden twins appears to have symbolic link, as all gave their lives to create the performance which demonstrates the bitter reality behind the creation of true illusion.

The scene in which we most fully connect with the birds visually is the depiction of Sarah’s suicide and her bid to escape her own entrapment. The scene, unlike the majority of others in the film, is not accompanied by dramatic music reminiscent of the stage and the drama genre; rather the silence increases our awareness of the birds. The audience then, can appreciate the beauty of their song however, instead of evoking images of pastoral scenes of freedom, Nolan utilises the symbolic use of locations to heighten this sense of claustrophobia. Scenes are largely centred through the public domain of the stage or in Borden’s room where the birds are kept as a symbolic source of illusion to aid the stage performance.

Moreover, the mise-en-scene is characterised by a darkness reflecting the mental state of Sarah, with the only light emerging from a large window, out of which, nothing can be seen. This only serves to enhance the tension, complying fully with the suspense thriller genre but it is likewise the interplay with the drama genre which allows Nolan to render the birds our primary focus. It is the birds’ sudden change in pitch and unexpected flight within the cage which equates for Sarah’s hanging and it is this which becomes the source of shock. In addition, it is also troubling that the bird noises continue as Sarah hangs, which demonstrates the futility of the illusion when compared with the lives lost, both human and animal. Nolan then, destabilises the idea of the bird being a symbol of creation in a magic trick, the bird in fact represents the ultimate entrapment and Sarah, who instead of emerging to great applause, joins them in the darkness. In addition, there appears to be a great authority given to the sound of the birds which links to ideas given in Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1790) in which he accounts for the ‘sublimity’ of the birds call which alters the way in which we perceive them and has a terrifying yet beautiful power all its own.[1] Indeed, in this section of the film the social structure of the scene implies that the birds are in a position of power, making the audience aware of Sarah’s death and perhaps also their own helpless situation.

Therefore, the birds metaphorise the relationship between illusion and reality and moreover, show how this connection leads to the degeneration of this society. Death increasingly appears to be transformed into a performance by Angier and Borden, both choosing to forget the pain of the bird or the agony of drowning, focusing only on the artistry and the prestige of being truly notorious. Indeed, throughout the film the audience assumes Angier and Borden embark on this process of self-sacrifice and destruction because of some overwhelming connection and competition with each other however, this impression ends with Angier’s statement that ‘it was the look on their faces’. This suggests that he thrives off the ability to shock his audience, an audience dominated by its era of rapid industrial, social and scientific advancement. Indeed, there was an undercurrent of fear in this post-Darwinian society that the human species was actually reversing the evolutionary process, descending instead into degeneration and becoming less civilised. Nolan foregrounds this idea by opposing the innocence associated with traditional magic tricks with their violent evolution in the film. These continual images of violence frame the film and suggest that despite the attempt to create an illusion there is always the inherent inescapability of reality.

Therefore, Nolan utilises the image of the canary bird to provide multiple metaphorical functions within the film which help to convey serious critiques on nineteenth century society. The use of the canary bird instead of the traditional dove is crucial to Nolan’s deconstruction of our preconceived ideas surrounding magic, as he visually and symbolically separates ideas of magic tricks being emblematic of innocence into his own very daring portrayal of man’s quest for infamy which descends into corruption. The bird represents through its own literal caging the metaphorical entrapment of Sarah and yet also the entrapment of the Borden twins and Angier, all bound by the illusion which eventually destroys them. The juxtaposition of the cage and the bird produces a very evocative image through the sheer unnaturalness of caging something which ought to be free. It is only in the suicide scene when Sarah regains her own autonomy that we obtain a true sense of the mastery of the bird and its overwhelming beauty. However, Nolan also uses the bird as a symbol for man’s degeneration in an increasingly progressive society, as the natural structures are able to be tampered with through modern science.

Personal reflection and connection to Ken Loach’s Kes (1969)

Lippit stated in Electric Animal: Toward a Rhetoric of Wildlife that human murder of animals is made possible by the metaphorical and visual deconstruction of animals’ into something ‘inhuman’.[2] This argument is interesting when analysed in relation to Ken Loach’s film Kes and to Nolan’s The Prestige, as in both films birds are killed brutally and at the hands of unrepentant humans. Lippit appears to suggest that as birds are without the ability to communicate verbally with humans, their capacity for personal reflection and resistance is limited and therefore, any emotional response can be separated by humans. However, both films explore the impact of this careless behaviour towards animals and as we see clearly through Billy’s inconsolable grief at the death of Kes and Nolan’s depiction of the close connection between the thoughtless treatment of Sarah and the caged birds, we see the consequences of separating emotions into ‘animal’ and ‘human’. Loach and Nolan appear to demonstrate that human treatment of animals is closely connected with their conduct towards humans and that such behaviours are never acceptable to either species.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Books

Altman, Rick, Film/Genre (London: BFI, 1999)

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion, 2002)

Burke, Edmund, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, ed. James T. Boulton, (Oxford, Blackwell, 1987)

Lippit, Akira Mizuta. Electric Animal: Towards a Rhetoric of Wildlife (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000)

Websites:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/films/2006/11/06/the_prestige_2006_review.shtml

https://www.lovefilm.com/reviews/The-Prestige

[1] Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion, 2002), page 11.

[1] Burke, Edmund, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, ed. James T. Boulton, (Oxford, Blackwell, 1987)

[2] Lippit, Akira Mizuta. Electric Animal: Towards a Rhetoric of Wildlife (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), p.168.