Animal Misunderstanding and Mystery in Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou

In The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou (dir. Wes Anderson, 2004) Zissou, the famous oceanographer, tackles familial issues while on board his ship The Belfonte. When Ned Plimpton, a man claiming to be his son, comes on board, Zissou’s marriage begins to disintegrate. This domestic upheaval takes place while Zissou simultaneously tries to film a nature documentary. The ship’s multilingual crew includes a Brazilian guitar player who sings Bowie hits in Portuguese, an Indian cameraman, a German second-in-command, and a group of unpaid college interns. The subject of Zissou’s film is the vengeful search for the elusive ‘jaguar shark’ that killed his friend, leaving The Belfonte’s crew bereft. Here, the film self- consciously works within an American literary tradition of marine vengeance that sees Martin Brody hunt a man-eating great white shark in Jaws (dir. Steven Spielberg, 1975), and Captain Ahab search for the great sperm whale that left him dismembered in Melville’s Moby Dick. Unlike these American classics, however, Anderson has Zissou decide not to kill the jaguar shark at the end of the film. Instead, he watches in awe as it swims past his submarine.

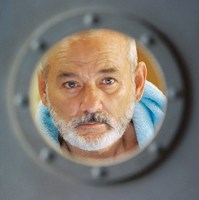

The self- referential style of Anderson’s oeuvre is particularly apparent in The Life Aquatic; the fact that Zissou is himself shooting a documentary foregrounds the metacinematic nature of the film. The pastiching of iconic real-life oceanographer Jacques Cousteau with the crew’s costume, references the tradition of nature films it critiques. The mise-en-scène is also significant, as through the perpendicular lines of the ship’s architecture, and its many portholes and windows, the cinema screen is regularly evoked. Anderson’s films are also ‘characterised by the curious mix of irony, comedy, and sincerity’. This is epitomised in the playful casting of the comedic actor Bill Murray as the glum Zissou, whose deadpan delivery of lines produces much of the wry, detached humour that permeates the film. The Life Aquatic engages with, perhaps, independent cinema’s most pervasive characteristic: its refusal to engage with Classical Hollywood conventions, deriving its identity from ‘challenging the mainstream’. One aesthetic example of this is Anderson’s employment of stop motion animation, which is used to portray many of the animals in the film, but most notably the jaguar shark. This ‘older technology, anomalous and arcane in the era of digital imagination’ (Past, p.63) illuminates Anderson’s refusal to participate in the special-effects driven Hollywood conventions that had seen Jaws’ huge box office success. The director also does this through a lack of concern with cinematic verisimilitude and a dedication to playfulness and style.

Through these indie movie characteristics, The Life Aquatic critiques its apparent cinematic opposite, the sincere, earnest world of documentary filmmaking. Jonathan Burt argues that ‘film images are fake by virtue of their cinematic artifice’, and so the documentary film’s generic insistence on authenticity and, especially in the case of the natural history documentary, scientific knowledge, comes into question. Anderson playfully undermines this self-proclaimed authority by emphasising the contrived nature of Zissou’s documentaries. The narrative of Zissou’s film is constantly shifting, most dramatically when Ned Plimpton comes on board the ship. Zissou sees the opportunity for ‘a relationship subplot’, exposing the filmmaker’s concern with entertainment over authenticity. Anderson explicitly comments on this through the character Jane Winslett-Richardson, a reporter sent to investigate Zissou’s filmmaking process. She tells him she thought some of his work ‘seemed slightly fake’, just as an orca whale swims, inexplicably, past the window. Zissou’s films are legitimised by his wife Eleanor, or rather, her scientific knowledge of animals. She tells him the ‘Latin names for all the fishes’, turning his adventures into legitimate, scientific, and therefore credible documentary films.

The Life Aquatic, however, mischievously disrespects scientific knowledge. Anderson presents the categorisation and naming of animals as nothing more than a paternal desire of ownership: Zissou changes Ned’s name to ‘Kingsley’, the name he would have chosen had he been involved in his upbringing. The bizarre nature of some of the animals’ scientific names, from the ‘Rhinestone Bluefin’ to the ‘Crayon Ponyfish’, holds up the act of naming for ridicule. Furthermore, the ‘Linguistic and multicultural miscegenation’ on board the ship adds to the general feeling of confusion in the film, which is ‘characterised primarily by misunderstanding’ (Past, p.55). Here, Anderson uses this confused tone to undermine natural historians’ arrogance, by showing Zissou and his crew constantly getting things wrong. In one scene, Eleanor remarks upon a couple of ‘mating’ Sugar Crabs. When one rips the claw off the other, Zissou asks confusedly, ‘Is that mating?’ The clear misunderstanding of the lives of the animals is perpetuated through Zissou’s documentaries, which package assumptions about creatures, and disperse them as scientific facts. This is illuminated through Zissou’s views on the two dolphins that swim by the ship as scouts; he remarks that ‘They’re supposed to be very intelligent, although I’ve never seen any evidence of it’. That the dolphins are humorously kitted out with special filming equipment but spend their time playing, emphasises how the cultural assumptions of animals are legitimised by scientific presentation, and therefore become fact.

Zissou’s preoccupation with naming, categorising and filming animals comes into conflict when he finally encounters the jaguar shark. Initially, the scene is presented as a turning point for Zissou. He cries at the sight of the shark and, as the ethereal Sigur Rós music plays, Anderson implies a point of catharsis for the character. After all, Zissou, in the end, does not kill the shark. As the film is a mocking of the earnestness of nature films, however, Anderson undercuts the sentimentality of the scene with his characteristically detached humour. Zissou says little about the shark, other than ‘It’s pretty good, isn’t it?’. While Burt states that ‘through postmodern notions of impossibility in animal representation’ film is ‘one more symptom of the disappearance of the animal modernity’ (Burt, p. 26), as much as is possible, Anderson attempts to avoid the disappearance of the jaguar shark. Zissou’s offhand adjective ‘good’, while initially acting as another source of deadpan humour in the film, is purposefully open. Here, Anderson has Zissou resist categorising the shark with words or action, leaving the creature to swim past, while his crew simply experience the encounter. Burt argues for the case of ‘animal as protean image, an object without resistance’ (Burt, p. 29), but Anderson attempts to resist this; the shark is not a villain, but just swimming past, and Zissou does not avenge the death of his friend, not because he has a new respect for the shark, but actually because there is no dynamite.

The representations of animals in the film are therefore used primarily to undermine the sincerity of nature documentaries. Anderson mocks the idea that scientific films are the only way to represent animals, a concept that hangs on the notion that there is a ‘true’ animal to be discovered. Anderson playfully ridicules scientists’ desire to ‘know’ animals by showing how Zissou and his crew constantly misunderstand the creatures they are filming. The exaggerated names of the creatures serve to provide The Life Aquatic with much of its wry humour by mocking the act of naming. Another way Anderson undermines nature documentaries is through the jaguar shark encounter. Instead of simply mocking the nature documentary film form, Anderson subtly offers up an alternative method of viewing animal encounters; not only accepting man’s lack of understanding, but relishing in it. By showing the wonder of animal mystery through the jaguar shark encounter, heightened by the visually arresting stop-motion animation, he reveals the value that can come from interactions with animals without a need for scientific knowledge. The stop-motion animation presents an animal so unlike those shown in earnest nature documentaries that the jaguar shark is displayed as a mystery that science cannot uncover.

The Life Aquatic has clear connections to Jaws, as both films are adventure stories of sorts, and follow the vengeful search for a shark. Anderson’s film, however, deviates from Hollywood conventions, through his highly stylised mise-en-scène and resistance to reach the same revenge resolution that Jaws does. Anderson’s self-conscious reworking of the iconic shark movie plays on audiences’ expectations of the revenge narrative, making Zissou’s inability to kill the shark therefore more significant. The film also has strong links to other Anderson films, for example Rushmore (dir. Wes Anderson, 1998), which similarly references the work of Jacques Cousteau. The Anderson film with the strongest link, perhaps, is Fantastic Mr Fox (dir. Wes Anderson, 2009), which employs the stop-motion animation used in The Life Aquatic. Anderson collides cultural understanding and scientific understanding of various countryside animals, playfully undermining the notion of a ‘truth’ about them. The film presents bizarre concepts, such as beagles love blueberries and badgers are demolition experts, as scientific fact, in the same way Zissou’s world believes that the two albino dolphins are ideal scouts. Anderson’s signature playfulness is perfect foil for the sincerity of the documentary and nature film, mocking the notion that there is a true animal to be discovered, and that science is the only way to find it. For Anderson, mystery is more fun.

Further References

Fantastic Mr Fox (dir. Wes Anderson, 2009, USA)

Jaws (dir. Steven Spielberg, 1975, USA)

Rushmore (dir. Wes Anderson, 1998, USA)

Bibliography

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London, UK: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2002)

Gooch, Joshua, ‘Making a Go of It: Paternity and Prohibitionism in the Films of Wes Anderson’, Cinema Journal, Vol. 47 No. 1 (Autumn 2007) <https://www.jstor.org/stable/30131997> [accessed 14 March]

Newman, Michael Z., ‘Indie Culture: In Pursuit of the Authentic Autonomous Alternative’, Cinema Journal, Vol. 48 No. 3 (Spring 2009) <https://jstor.org/stable/20484466> [accessed 14 March]

Past, Elena, ‘Life Aquatic: Mediterranean Cinema and Ethics of Underwater Existence’, Cinema Journal, Vol. 48 No. 3 (Spring 2009) <https://www.jstor.org/stable/20484468> [accessed 14 March 2015]