Disney’s animated comedy feature The Emperor’s New Groove follows the journey of a selfish Inca Emperor, Kuzco, who is transformed into a llama by his megalomaniac royal advisor, Yzma. In order to revert back into his human self and stop Yzma from taking over the Inca Empire, Kuzco persuades the gullible yet good-natured peasant Pacha to help him under the conditions that once human again, Kuzco will abandon his prior plans to destroy Pacha’s village and build his dream pool elsewhere.

Primarily aimed towards families and children, The Emperor’s New Groove parodies the comedic tone and style conventional to the sub-genre of ‘buddy’ movies but with a family-friendly narrative twist featuring animal transformation. Kuzco’s unintentional transformation occurs during Yzma’s dinner party sequence, where she maliciously plots to poison Kuzco in order to take over the empire and become the new ruler. However, Yzma’s dense, clumsy sidekick Kronk accidentally mixes the wrong potion into Kuzco’s drink which instead transforms him into a llama. Though at first the potion appears to have killed Kuzco, John Debney’s light-hearted, whimsical score suddenly becomes more abrupt and syncopated with Kuzco’s unexpected movements as he regains consciousness from the potion. Debney’s playful score grows in intensity as the spectator along with Yzma and Kronk witness an unknowing Kuzco transform into a llama, with the score still remaining in sync to Kuzco’s bizarre change of appearance. Kuzco’s growing ears (figure 1) and neck along with the replacement of his hands with cloven hooves (figure 2) are all depicted humorously as the spectator watches Kuzco’s metamorphosis from a point-of-view shot through the eyes of Yzma. Purple ‘magic’ Inca symbols are also used to signify Kuzco’s animal transformation to younger spectators, with the genre of animated, family-friendly films often relying on visual clues to help guide younger audiences on what is happening within the narrative.

Figure 1 – Kuzco’s transformation begins.

Figure 2 – Kuzco becomes a llama.

The decision to use a llama as Kuzco’s animal counterpart is arguably due to the significance of llamas in Incan society, as historically, ‘llamas were the Incas’ most important domestic animal, providing food, clothing, and acting as beasts of burden. They were also often sacrificed in large numbers to the gods’[1]. It is therefore both symbolic and comedically ironic that Kuzco, an emperor treated like a god, is transformed into an animal that would have been sacrificed in large quantities as offerings to the gods. The irony of this antithesis represents not only the dry, comedic tone of the film but also suggests that Kuzco will embark on a psychological transformation, along with this physical animal transformation, to change his self-obsessive, egotistical ways through this new, zoomorphic form. As the Sapa Inca, a name given to the leader / emperor of the Inca’s ‘meaning the only Inca or One True Inca’[2], Kuzco has been showered with nothing but luxuries and riches by his subjects. However, as a llama, Kuzco cannot rely on this title and therefore must now experience what it is like to be ordinary in an empire that revolves around him. Disney’s decision to use animal transformation to symbolise character growth is also due to the attraction of animal-based narratives, as ‘box office returns reflect the enduring popularity of animal narratives, they also make apparent the economic dimension of such representations: animal stories are profitable’[3]. The representation of character growth through animal transformation not only comedically symbolises Kuzco’s change from God-like ruler to lowly llama but is also used by Disney to commercially attract a wider audience due to the profitable appeal of animal-orientated narratives in film.

Figure 3 – gold llama.

Figure 4 – llama in early Inca civilization Machu Picchu.

After Kronk’s failed attempt to ‘dispose’ of llama Kuzco at Yzma’s behest, a local peasant, Pacha, unknowingly transports a sack containing the emperor from the palace to his village. Unable to tell his wife about the emperor’s plans to tear down their home, Pacha instead sentimentally observes their ancestral family hut one last time before resting his eyes on a llama carving (figure 5). A close-up, point-of-view shot of Pacha’s hand touching the carving (figure 6) shows his connection to the animal, with both Pacha and the Inca llama symbolising the hard-working, domesticated, and undervalued sector of Kuzco’s empire. Like the llama, Pacha represents dependability and kindness – qualities of which vastly differ from Kuzco. Pacha’s occupation as a llama farmer presumably passed down from his father also reinforces the llama as a symbol personal to Pacha connoting stability and paternal love. Contrary to this, Kuzco’s lack of a paternal figure suggests the reasoning for his materialistic personality stems from the absence of family within his life. By becoming the llama, spectators are encouraged to wonder if the lonesome, narcissistic ruler will change his ways through gaining a family in the paternal, family-orientated figure of Pacha.

Figure 5 – Pacha looks at llama carving.

Figure 6 – close up of Pacha tracing the llama carving.

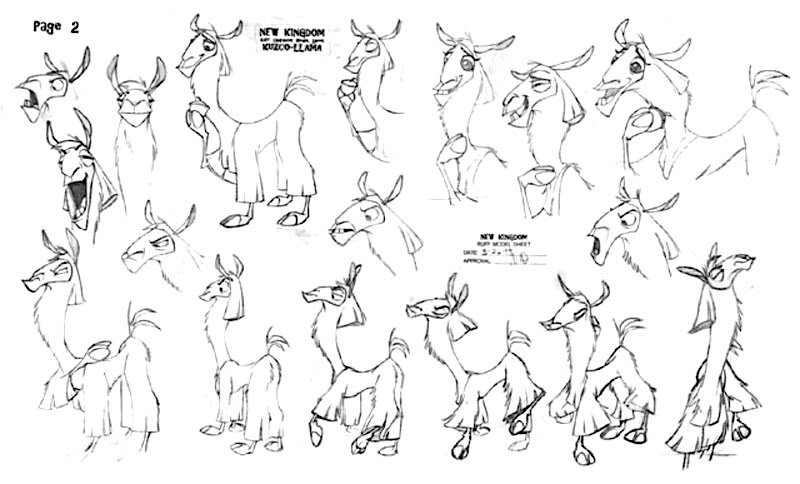

Pacha returns back to his cart only to discover the body of an unrecognisable llama inside the sack. Once Pacha realises the llama can anthropomorphically talk, Debney’s high-energy score intensifies to highlight the panic of both characters, as Pacha believes Kuzco is some form of ‘demon llama’ and Kuzco relates Pacha’s fear to the regular llama behind him. Still unaware he too is also a llama, a fast-paced tracking-shot of Kuzco running away becomes comedic as Kuzco changes from running with two legs to running with all four of his new quadrupedal feet. Unfortunately for the emperor, he soon quickly stumbles over his newly transformed body, with an upside-down shot from Kuzco’s perspective of a horrified Pacha (figure 7) used to place the spectator in Kuzco’s disorientated body. The animated character design of llama Kuzco (figure 8) nevertheless retains his facial expressions, hairstyle, and eye shape / colour, suggesting that ‘animation can wholly preserve the nature of the beast while still invoking human characteristics, and the therianthropic image can be a conventional representation in animation, largely through the ways the design and execution of a character occurs’[1]. Kuzco’s llama counterpart is also designed specifically through a westernised lens, as ‘exotic as the llama is, Disney nonetheless Americanizes and culturally domesticates it for the US viewing public. In Groove, there is an unremitting insistence on pronouncing the word llama (‘yama’) as lama’[2]. Kuzco’s metamorphized, animal body resembling characteristics of his human self therefore not only creates cohesion between the two designs, which makes it easier for younger spectators to recognise that the llama and the emperor are the same character, but also assimilates the Incan identity of the llama for a primarily westernised audience.

Figure 7 – upside-down shot of Pacha.

Figure 8 – Kuzco’s llama animated character design.

Now aware of his zoomorphic appearance, an amnesiac Kuzco manipulates Pacha to help take him back to the palace where he believes Yzma will gladly help change him back to his human self. Along the journey, Kuzco is forced to rely on his animal characteristics as a llama to survive. However, Kuzco’s submission into becoming more ‘llama’ contrarily grounds the character into adopting more humane and empathetic qualities, both of which he desperately lacked as a human. During the scene where Pacha and Kuzco find themselves in grave danger stuck at the bottom of a ravine with crocodiles beneath, it is Kuzco’s zoomorphic ability to extend his long, llama neck (figure 10) which enables Pacha to grab onto some hanging rope and pull them to safety. Their collaborative teamwork along with Kuzco’s surrender to embrace his metamorphized body suggests that Kuzco’s egocentric, selfish ways are beginning to change. Kuzco also manages to use his mouth to grab Pacha to safety during this scene after the ground gives away under his feet, with Kuzco practically utilising this new body to help others rather than simply himself. The triumphant, gleeful non-diegetic score present within the scene also highlights the importance of Kuzco’s first altruistic act, as comedic, fast-paced shot-reverse-shots of the two characters discussing Kuzco’s new-found heroism further emphasises how astounding this change in behaviour is. An astonished Pacha learns from this act that Kuzco’s attitudes towards others has the capacity to transform during his experiences as a llama, with Pacha and Kuzco’s friendship now evolving in symbiosis with Kuzco’s maturing disposition.

Figure 9 – Pacha and Kuzco work together.

Figure 10 – Kuzco uses his llama neck.

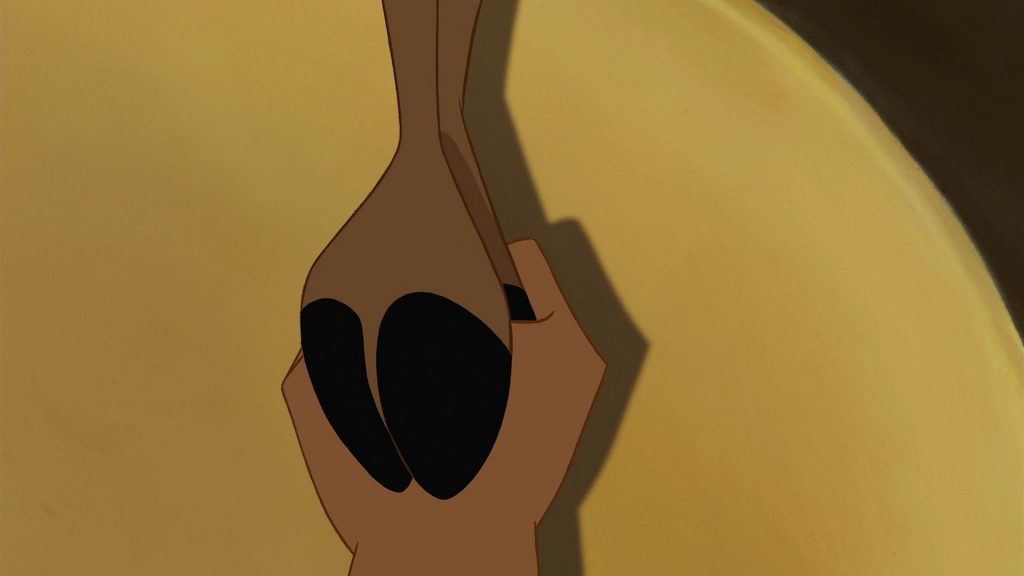

During the climax of the film, Kuzco and Pacha’s successful teamwork on the ravine is paralleled to reflect Kuzco’s full-circle journey. When faced with choosing between retrieving Yzma’s vial (which will turn him back into a human) or saving Pacha from falling to his death, Kuzco chooses to save Pacha, thus cementing Kuzco’s emotional evolution. A close-up shot of Kuzco’s cloven hoof holding Pacha’s hand to prevent him from falling (figure 11) signifies Kuzco’s selfless decision to save his friend before himself, with the image of the embraced hoof and hand a symbol of the close friendship which exists between the animal and human. In this scene, Kuzco finally exhibits the characteristics and spirit of Inca’s dependable llama, as he has learnt through Pacha the valuable moral to help others before himself. Through eventually embodying the llama in both spirit and appearance, Kuzco proves himself not only as a changed man, but as a great and dependable friend. Fortunately for Kuzco, his act of kindness is rewarded as he receives another chance to retrieve the vial. By working with Pacha in a similar fashion to their teamwork on the ravine (figure 12), the duo is able to successfully defeat Yzma and recover the vial. Like the previous scene on the ravine, wide-shots of the two characters working together arm-in-arm combined with Debney’s light-hearted, amiable non-diegetic score highlights the growth of Kuzco and Pacha’s friendship as equals, not as animal and human or ruler and subject. The relations between animal and human are consequently represented in The Emperor’s New Groove through Pacha and Kuzco’s balanced friendship, with both characters now viewing the other as equal despite Kuzco’s animal transformation and Pacha’s lower social class.

Figure 11- close-up of Kuzco saving Pacha.

Figure 12 – wide-shot of Kuzco and Pacha working together.

To conclude, The Emperor’s New Groove uses animal transformation to both physically and symbolically represent character change. Through human to animal metamorphosis, Kuzco learns important morals and the value of friendship by coming to terms with his modest, llama counterpart in the good-natured, paternal company of Pacha. The llama subsequently is represented as a symbolic emblem for Kuzco’s undervalued, working-class subjects, as it is through becoming the llama that enables Kuzco to gain more humanity and compassion towards Pacha’s community. To complete Kuzco’s transformative journey, the emperor decides to abandon his selfish plans to destroy Pacha’s home once and for all. Kuzco’s internal transformation is illustratively reflected through Pacha’s wife gifting an appreciative Kuzco a poncho bearing the image of a llama. Touched by this thoughtful gift, Kuzco proceeds to wear the llama poncho with pride (figure 13) as his human self now exhibits selfless characteristics associated with the spirit of the Inca llama. The Emperor’s New Groove’s animal transformation narrative subsequently ends with Kuzco embracing his humbled experiences as a llama, with Kuzco no longer materialistically driven by his own selfish desires now that he has gained something infinitely more valuable – a family

Figure 13 – Kuzco receives a symbolic gift.

Figure 14 – Kuzco is accepted by Pacha’s family.

Bibliography:

[1] BBC, ‘Inca Gold Llama’, BBC, <https://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/l83ZQ7grS9iS0D84X8HRuA> [accessed 16 January 2022].

Dindal, Mark, dir., The Emperor’s New Groove, (Walt Disney Pictures, 2000)

[2] History Histories, ‘The Sapa Inca’, HistoryHistories, <http://www.historyshistories.com/inca-the-sapa-inca.html> [accessed 16 January 2022].

[3] Molloy, Claire, Popular Media and Animals, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), p. 1.

[1] Wells, Paul, The animated bestiary : animals, cartoons, and culture, (Piscataway: Rutgers University Press, 2008) p. 71.

[2] Silverman, Helaine, ‘Groovin’ to Ancient Peru’, Journal of Social Archaeology, 2.3 (2002), 298–322, (p. 307).

Further Reading:

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion, 2002)

Ebiri, Bilge, ‘We’ll Never Make That Kind of Movie Again’ An oral history of The Emperor’s New Groove, a raucous Disney animated film that almost never happened’, Vulture, 2021, < https://www.vulture.com/article/an-oral-history-of-disney-the-emperors-new-groove.html> [accessed 19 January 2022]

Wakild, Emily, ‘Llamas are having a moment in the US, but they’ve been icons in South America for millennia’, Boise State University, 2021, <https://www.boisestate.edu/bluereview/llamas-are-having-a-moment-in-the-us-but-theyve-been-icons-in-south-america-for-millennia/> [accessed 19 January 2022]

Figures:

Figure 2 – BBC, ‘Inca Gold Llama’, BBC, < https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00tn9vj> [accessed 19 January 2021]

Figure 3 – Davies, Josh, ‘The rise and fall of the Inca Empire is recorded in llama poo’, National History Museum, 2019, <https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2019/january/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-inca-empire-is-recorded-in-llama-poo.html> [accessed 19 January 2021]

Figure 8 – Character Design References, ‘art of The Emperor’s New Groove’, character design references, <https://characterdesignreferences.com/art-of-animation-8/art-of-the-emperors-new-groove> [accessed 19 January 2022]