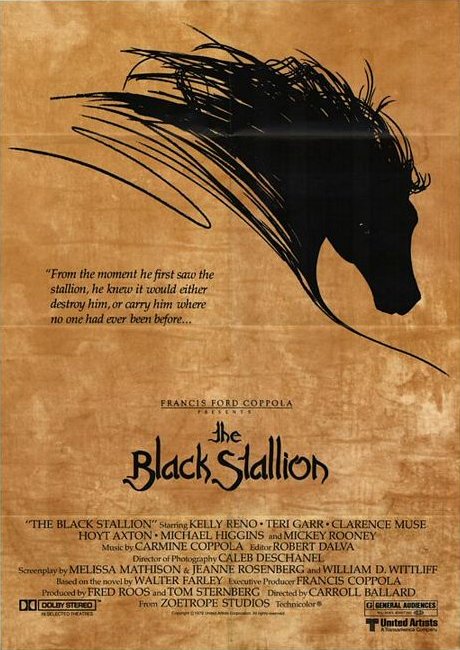

The Black Stallion (1979) Dir. Carroll Ballard

Pulled to the tropical shores of a desert island by a wild Arabian horse following a shipwreck, The Black Stallion follows the narrative of an unbreakable bond between boy and horse, man and beast. The only remnants of the shipwreck that remain are the black stallion (The Black), the boy (Alec) and the two objects given to him by his father; a small figurine of Bucephalus and a knife. Passed down to him, both generational tools of masculinity represent his ascent into adulthood as the narrative embarks on a young boy’s epic journey into autonomy. Taming the mysterious wild beast and riding him to victory acts as an exploration of Alec’s personal coming-of-age story. Their alliance fractures archetypes of animal-human relationships as he introduces the mystical, Arabian figure into the implicitly white, middle-class, human world of racing. It’s inspiring at times, ethically passé at others, but always interesting in its exploration of The Black as a symbol of masculine power; an extension of Alec’s physical, emotional and sexual development into manhood.

As a product of Twentieth Century Fox, The Black Stallion partakes in the tradition of genre hybridity. Ballard adapts Walter Farley’s original children’s story to broaden the film’s mass-market appeal by combining Family Film with Action and Adventure, resulting in an intimate Bildungsroman narrative. This narrative explores ‘the inner life of the protagonist’[i] and investigates how ‘his self-realization become[s] an important element along with the unfolding of the whole person’.[ii] The gradual ‘unfolding’ of the coming-of-age narrative reveals an abundance of psychological and moral growth in Alec, and a self-determination that epitomises the action hero. O’Brien explains that ‘the hero in an action movie is very much an agent of will: a paradoxical figure of both compulsion and command’[iii], an idea reinforced by the pivotal moment Alec insists ‘I gotta ride’[iv].

Furthermore, expansive shots of an exotic desert island situates Alec and The Black’s communal development, grounding the film in its Action and Adventure context. Obstacles stand in the way of Alec’s ambitions of unanimity between man and horse, and the ‘feel good’[v] response that the Family Film attempts to produce. The final race is an emphatic actualization of his Father’s Bucephalus prophecy. Alec’s ambitions reach fruition as he competes The Black in a climatic race of macho power-struggle. In his victory he re-establishes the family unit and gains his acceptance into an exclusive male world. This is an example of when ‘the family film gives its audience a sequence of concrete instances for the testing and re-affirmation of a fundamental belief in the virtues of family life’.[vi] Thus, The Black Stallion stresses the importance of the generational bond and maintenance of an archaic, chauvinist gender hierarchy.

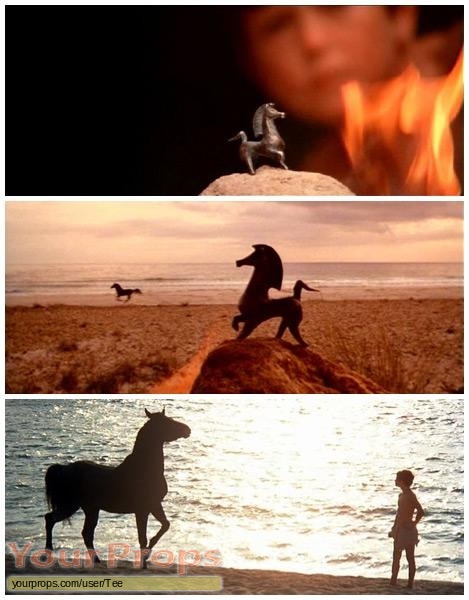

The symbolism of the powerful horse is one that reverberates through literary and aesthetic history. Tyler explores the importance of ‘the American man-horse’[vii] in the context of the American film industry, he explains that ‘The horse is not only a power symbol as a fleshy engine but as an extension of the man’s personal power, and more specifically, of his sexual power’.[viii] Their speed, elegance and freedom of movement provides a perception of mastery and control that empowers its male, human counterpart. As Alec creates fire with his bare hands, he performs an ancient ritual of manhood. Ballard uses a deep focus shot that pans out to show the Bucephalus statuette and The Black galloping valiantly across the shore throughout the fire-making process. The mise-en-scène’s majesty confronts the viewer with a visually powerful symbol of male independence and sovereignty, a notion underpinned by The Black’s unrefined autonomy. Moreover, the horses in The Black Stallion belong to an implicitly male world and female characters have no true influence. His mother supports and accommodates his transition into adolescence as he succeeds in fulfilling his Father’s legacy, ensuring there are no tensions within the representation of the family unit.

Through the polarity in Napoleon and The Black’s characterisations, the only two horses within the narrative, both male, represent the struggle in harnessing prepubescent manhood. Napoleon epitomises this mastery of this self-control. Nappy and Snoe act as examples for the possibilities of Alec and the Black’s development. The purity in Napoleon’s white complexion juxtaposes the Black’s dark and foreign, almost preternatural, appearance. The Orientalism within the film creates hyperbolic representations of differing ethnic groups whereby ‘The filmmakers inaccurately portray people, country, customs, and/or beliefs for their own benefit’.[ix] This inaccurate portrayal can be seen in the contrasting figures of Nappy and Snoe. Napoleon represents a domesticated completion of the Black; an Arab horse, or ‘other’, that has been successfully introduced into a human world to live in harmony with the Western man. Released during the Oil Crises of 1979, The Black Stallion echoes the global politics of its time. The oil embargo, imposed by Middle Eastern Countries, functioned as a catalyst for long-stemming intercontinental tensions between the East and West.[x] These frictions are prevalent in the representation of the Arab men. They are portrayed as barbaric, turbaned figures that undergo no narrative development and operate only as a dangerous symbol for the foreign ‘other’. In taming The Black and racing him into the victorious stands of a white, Western world, Ballard portrays an image of American superpower controlling the wild, Middle Eastern ‘other’. Thus re-establishing a narrative of American supremacy through the form of a seventeen-year-old boy fulfilling the American dream.

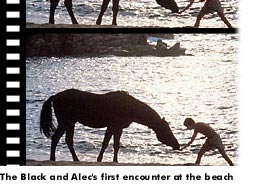

Alec and the Black’s friendship is one of beauty and trust. Ballard creates a visual poetry in exploring their animal-human co-dependency. During their first meeting, Ballard creates edited shifts in perspective as he moves from Alec’s point-of-view shot to The Black’s. The over-arching, non-diegetic sound of a heartbeat links the two perspectives and creates dramatic apprehension. Through this visual representation of unity, Ballard explores their connection as supernatural and intrinsic. In this symbolic use of editing, Ballard creates the image of a singular soul inhabiting two separate, yet innately connected, entities. Further symbolism of the sublimity of the animal-human bond is portrayed as they meet again on the desert island. It appears as though Alec and The Black have their own language. Foregrounded by the non-diegetic tribal sound of a drum, Alec and the Black embark on a ceremonial, interpretive dance of trust between Man and Beast, a series of shots follows their silhouettes against a glistening auburn sunset as a filmic medium of shadow-play. Furthermore, Ballard creates an aesthetic euphoria through the use of organic water imagery as they swim together. Alec and the Black initiate a beautiful, underwater imitation of the pas de deux in a symbolic representation of reciprocal love; an emphasis of their unity. The beat of the singular tribal drum is now interspersed with the sounds of a grandiose Western orchestra, represented as a climatic completion to their ceremonial dance and a celebration of their co-existence. This use of visual poetics stresses the interdependence of human-animal co-inhabitancy as two evolutionary components that construct the world of today.

Interestingly, other animals within The Black Stallion are represented as a threat. The birds in the barn taunt Alec and persist as physical barriers to their union and the owls are utilised as a gothic trope to incite fear and apprehension. The cobra is symbolic as the harbinger of death and the close up shots of it hunting Alec create emphasis on the diegetic sound of the snake. Carmine Coppola, Father of renowned Hollywood director Francis Coppola, synthesises human breathing with the hissing of a serpent to create a parcel tongue of sorts. This use of anthropomorphism is terrifying and represents the disturbing threat of a non-domesticated animal, untamed by the human world, encroaching on and endangering human existence. Ballard creates a paradoxical tension in the representation of animals as a whole, the film’s notion of freedom is undermined by the restraints of the human world the animal is thrust upon. The Black is allowed to be free, but only in an understood human construct of freedom that is typified by suburban fences.

However, The Black Stallion focuses on animal magnificence and human audacity, and how both are combined to portray an all-encompassing exploration of power and masculine mastery. To pacify and moderate a wild and unbroken horse is a figurative challenge of maturity. Through his relationship with The Black Alec achieves a state of heightened consciousness and an instinctive, primal authenticity is derived from their union. Nevertheless, the film marginalises any other groups of society that exist outside the male ego. As an emblem of freedom, The Black represents the spheres of male-only liberty and exists as a symbol of juvenile fantasy, a desire of complete autonomy away from parental authority. A freedom that is established away from the interfering outsider that obstructs the endeavors of boys and men.

Due to its intimate focus on the emotional relationship between the horse and the human, the most interesting similarity is of Black Beauty (1994). Both The Black and Black Beauty are a symbol of freedom and heroism. However, Black Beauty endures the oppressive brutality of the humans, whilst The Black aids them in their recognition of dominance and authority, eventually adapting to successfully function within a human world by becoming one of them. A moral thread permeates Black Beauty as Thompson explores the issue of animal cruelty, contrasting the ethical concerns of The Black Stallion which focus on human self-discovery and male governance. Thompson utilises the emblem of the horse to communicate issues regarding the animal, whereas Ballard uses the horse to portray the matters of the human. An interesting amalgamation of the two can be seen in The Horse Whisperer (1998), where Redford focuses on the fragile nature of human dominion over animals in a rare projection of untainted communion between mammals of different species.

[i]Esther Kleinbord Labovitz, The Myth of the Heroine: The Female Bildungsroman in the Twentieth Century, 2 edn (New York: Lang, 1988), p. 55.

[ii]Esther Kleinbord Labovitz, The Myth of the Heroine: The Female Bildungsroman in the Twentieth Century, 2 edn (New York: Lang, 1988), p. 55.

[iii]Harvey O’Brien, Action Movies: The Cinema of Striking Back (London: Wallflower Press, 2012), p. 3.

[iv] The Black Stallion, dir. by Carroll Ballard. Twentieth Century Fox, 1979

[v]Noel Brown, ‘The ‘Family’ Film and the Tensions Between Popular and Academic Interpretations of Genre’, Trespassing Journal: an online journal of trespassing art, science, and philosophy 2, (2013), P.7

[vi]Paul Loukides, Beyond the Stars 2: Plot Conventions in American Popular Film, ed. by Linda K Fuller (London: Popular Press 1, 1991), p. 93.

[vii]Parker Tyler, Sex, Psyche, Etcetera in the Film (Baltimore: Pelican Books, 1969), p. 31.

[viii]Parker Tyler, Sex, Psyche, Etcetera in the Film p. 31.

[ix]Modern Orientalism, Orientalism in Modern Pop Culture (2016), <http://modernorientalism.weebly.com/film.html> [accessed 24 January 2016].

[x]CBC News, The Price of Oil- In Context, <https://web.archive.org/web/20070609145246/http://www.cbc.ca/news/background/oil/> [accessed 18 November 2015].

Further investigations…

Walter Farley super-fan sight, including movie/book reviews etc.: http://theblackstallion.com/web/category/media/

Journal article:

Steve Vineberg, ‘The Magician’, The Threepenny Review, .108, (2007), 28-31.

Very interesting analysis of the film:

Ellen Seiter, ‘The Black Stallion: A Boy and his Horse’, Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, .23, (1980), 38-39.

Media to go with article:

YouTube link for cobra scene:

YouTube link for original trailer for film: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8GlZJ4wVLdA