Disney’s The Aristocats[1] follows a family of pet cats who are stolen from the house of Madame Bonfamille, a Parisian aristocrat, when her butler, Edgar, discovers that they will inherit the estate before him. Edgar drugs and abandons the cats in the countryside outside of Paris, presuming that they will be lost forever; however he doesn’t count on their having help from the charismatic Thomas O’Malley: an alley cat voiced by Disney veteran, Phil Harris. With the help of O’Malley and a few stray friends, Duchess and her kittens find their way home across Paris and succeed in foiling Edgar’s plan by shipping him off to Timbuktu in a trunk- perhaps a slightly harsh punishment for a man who simply wants an inheritance after many years’ loyal service…

The genre of family films possesses several key tropes, many of which are present in The Aristocats. The first of these is that the animals in the film are heavily anthropomorphised, with many, if not all of the animals wearing clothes and taking on the characteristics of humans. Many family films, and Disney films in particular, depict a complete family unit, and The Aristocats is no exception, with the family name ‘Bonfamille’ offering the literal translation of ‘good family’. I use the word ‘complete’ to describe this set up, in the sense that generally, in family oriented films, we see a family unit consisting of a mother, father and children, with the male of the family taking on the role of provider whilst the female provides nurture, in typical gender stereotype. As such, the family of cats is presented as incomplete before Duchess meets Thomas O’Malley who steps immediately into the role of father, without whom the classic happy ending would not be possible. A large number of Disney films employ a somewhat bourgeois version of the Deus Ex Machina, that is, a filmic or literary device used to solve a seemingly unresolvable plot issue in a way that is not necessarily a logical step relating to the progression of the story thus far. In the case of most Disney features, this serves to create a unifying aspect by the end of the film and sets the world to rights in one stroke, however unrealistic this may be. For example, in 101 Dalmatians[2], Roger and Anita decide to create a Dalmatian plantation to deal with the issue of finding homes for ninety nine puppies, in order to avoid rehoming them all, which might be a distressing ending for a child audience. Similarly, The Aristocats ends with Madame Bonfamille opening her home to all of the stray cats of Paris, with both endings set to an uplifting song which fritters away any issues the audience may have concerning these rather flawed solutions. It is interesting to note that, due to the hand-drawn animation style being particularly laborious, the animators have reproduced patterns of movement from earlier Disney films in several places, such as the removal truck from 101 Dalmatians:

In a similar way to Disney’s Robin Hood[3], Reitherman takes a ‘Humanimal’[4] approach to the portrayal of animals in that the animal presence in The Aristocats serves not as a critique of the behaviour of animals, but humans. The fact that the animals in the film are representative of humans is made apparent through several inconsistencies in their behaviour and appearance which serve to anthropomorphise the characters, such as the issue of the cats not having slit pupils as they should in an animalistic depiction. The animal characters often wear items of clothing such as Scat Cat’s hat and Duchess’ collar, which appears to be more of a jewelled necklace, as well as Roquefort the mouse sporting a Sherlock Holmes-esque outfit to show that he has taken on the role of investigator in the cats’ disappearance.

As The Aristocats was produced at a point when there was more equality between classes than at the time the film was set, it possesses a certain amount of conflict and ambiguity concerning the benefits of an integrated society. Set in 1909, Reitherman uses the characters of Duchess and the kittens to mirror the behaviour of Parisian aristocracy at the time, with Duchess instructing the kittens on how they should act if they wish to be proper ‘ladies and gentlemen’. Toulouse, Berlioz and Marie are encouraged to take up pursuits that are ‘appropriate’ for the upper classes such as painting, music and singing and are reprimanded for ‘biting and clawing’, thus separating them from the lower classes and also from any inherent animal nature.

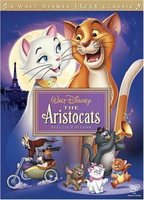

This is somewhat troubling as it encourages young children watching the film to notice class distinctions and to form superior opinions of themselves whilst looking down on others, and also promotes a lifestyle of leisure where you are not required to work for what you have or learn skills that will aid you in life. This ‘us and them’ focus can be seen both in the titular song that describes aristocats as never being found ‘around garbage cans where common kitties play’ and by Toulouse’s indignation at the truck driver calling the family of cats ‘tramps’. With these prejudices in mind, the scene where Roquefort the mouse appears to be chasing the gang of stray cats becomes a direct attack on integration between classes; with the alley cats (or lower classes) running to the aid of the aristoc[r]ats, they are going against the natural order, to the extent that the stereotypical French man that witnesses this pours away his bottle of wine, as he believes that he is hallucinating. It is interesting to note the differing packshots for each edition of the film released since the original in 1970, as each portrays social class slightly differently:

The polished, ‘Christmas card’ portrayal of a family in the first image shows little integration between social classes as it would appear that Thomas O’Malley has become a part of the aristocracy and retains none of his lower class attributes. The contrived appearance of a portrait leaves no opportunity to include images of the streets on which the majority of the film takes place, and suggests an exclusion of the outside world by placing a window in the background. Both of the other packshots include images of the alley cats, or at least some hint that there is integration between different classes in the film. However, with the image on the second packshot appearing to be made entirely of one scene, the elevated position of the well groomed Thomas O’Malley and Duchess watching the children play in the gutter suggests that there is still a certain amount of condescension where ‘lower class’ behaviour is concerned, as they are literally looking down on them. In contrast, the ‘Special Edition’ depicts O’Malley as an unkempt alley cat on an equal level with Duchess, rather than being changed into ‘one of them’ to elevate his status. The progression of these portrayals suggest a change in Disney’s position on class over time, with each packshot representing the most desirable aspects of the film, from the upper classes being distanced from the rest of the world, to a fully integrated society as depicted on the ‘Special Edition’ cover.

Another key reflection on society that The Aristocats produces is that of gender stereotypes and in particular, the idea that a woman’s role is to be constantly charming, accomplished and appealing to men. Duchess, unlike any of the other cats, is constantly unruffled and perfectly courteous in every exchange, just like her owner, as if they are both considered to be ‘the women of the house’. The similarity in the two characters’ roles can be seen when Madame Bonfamille says that they ‘must both look [their] best for Georges’, demonstrating the importance of feminine charm and appearance. Madame Bonfamille also suggests when Thomas joins the family, that they ‘need a man around the house’, as if a woman cannot be happy on her own. When Duchess plays the harp in ‘Everybody Wants to be a Cat’, it appears as though all of the ‘men’ in the room are placed in some kind of trance by her seductive voice, suggesting that a woman’s power lies in her feminine accomplishments such as singing and music.

Both Marie and Duchess are presented as damsels in distress throughout the film, just as many human women are portrayed in Disney films, with the exception of characters such as Mulan[5] in her film of the same title, and Merida in Pixar’s Brave[6], begging the question of whether young audiences should see these characters as role models. Marie falls off of both a train line and a truck, relying on Thomas O’Malley to save her- presumably as her mother would be incapable of such a feat or should not be shown jumping into a river as these are more ‘manly’ activities. When O’Malley first meets Duchess and doesn’t know that she has children, he appears to be a womaniser, yet immediately takes on the role of protector once he discovers the kittens, thus demonstrating two prominent male stereotypes. The kittens yearn throughout the film for a father figure and become attached to Thomas O’Malley as a strong male role model, who by the end of the film completes the classic family unit of two parents plus children, as previously mentioned. This is an element which is also present in films such as Lady and the Tramp[7], with the film ending with the two dogs and their puppies having a family photo taken, just as the cats do at the end of The Aristocats. In Lady and the Tramp, the genders of the puppies are distinguished by their similarity in appearance to either their mother or father, with none of them being cross breeds as they should be, having parents of different breeds. As with The Aristocats, this suggests that Disney’s idea of gender is entirely reliant on outward appearance; as the film has established until this point what a male and female should look like and what character traits they should possess by using the models of Lady and Tramp, the puppies are depicted in the same way to infer that they also have these same qualities.

Disney films depicting animals, like many within the genre of family entertainment, function by appealing to both children and adults alike through their familiar depiction of family life. By presenting controversial topics such class and gender in the form of a children’s film, Disney trivialises their importance by depicting these issues as a natural part of human life and appealing to an audience that will not understand them, and may see the characters as role models. However, by including these stereotypes in such a widely distributed genre of film, they are placed under scrutiny by bringing them to the forefront of public consciousness, allowing the audience to form their own opinion on the issues raised.

Filmography:

The Aristocats. Dir.Wolfgang Reitherman. Disney, 1970.

101 Dalmatians. Dir. Clyde Geronimi, Hamilton Luske and Wolfgang Reitherman. Disney 1961.

Brave. Dir. Mark Andrews, Brenda Chapman and Steve Purcell. Disney, 2012.

Lady and the Tramp. Dir. Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson and Hamilton Luske. Disney, 1955.

Mulan. Dir.Tony Bancroft and Barry Cook. Disney, 1998.

Robin Hood. Dir. Wolfgang Reitherman. Disney, 1973.

Bibliography:

Paul Wells, The Animated Bestiary (London: Rutgers University Press, 2009)

Suggestions for further reading:

Malfroid, Kirsten, ‘Gender, Class, and Ethnicity in the Disney Princesses Series’ [accessed 26.11.2013]

https://lib.ugent.be/fulltxt/RUG01/001/414/434/RUG01-001414434_2010_0001_AC.pdf

Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary (London: Rutgers University Press, 2009)

[1] The Aristocats. Dir.Wolfgang Reitherman. Disney, 1970.

[2] 101 Dalmatians. Dir. Clyde Geronimi, Hamilton Luske and Wolfgang Reitherman. Disney 1961.

[3] Robin Hood. Dir. Wolfgang Reitherman. Disney, 1973.

[4] Paul Wells, The Animated Bestiary (London: Rutgers University Press, 2009), p.53

[5] Mulan. Dir.Tony Bancroft and Barry Cook. Disney, 1998.

[6] Brave. Dir. Mark Andrews, Brenda Chapman and Steve Purcell. Disney, 2012.

[7] Lady and the Tramp. Dir. Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson and Hamilton Luske. Disney, 1955.