A modern twist on the traditional fairytale story of Rapunzel, Tangled is an edgy take on a timeless classic. Disney’s 50th animated family film is a fantasy, fairytale, romance, comedy and musical. Set in a fantasy kingdom far-far away, the King and Queen’s baby daughter Rapunzel is stolen by the evil Mother Gothel, who wants to use Rapunzel’s hair for its magical healing properties. Gothel imprisons the young princess in a hidden tower; 18 years pass and the lost princess and her pet Chameleon, Pascal, have a dream to escape the tower and watch the golden lanterns. Pascal is a cheeky, trustworthy best friend who does not speak, but instead his quirky character is communicated through rapid colour changes, his sharp, feisty attitude and grit determination.

Enter the mysterious Flynn Ryder who promises to take Rapunzel to see the golden lanterns. It is almost too good to be true for Rapunzel’s Prince Charming is actually a common thief. The palace horse Maximus will not stop until Ryder has been successfully captured. Maximus is a proud individual, filled with self-importance which makes for many comic scenes especially with his highly animated tracking abilities. Rapunzel’s feminine charm leads the hybridised horse-dog Maximus to postpone the official chase of Ryder until after the ceremony of the golden lanterns. Pascal and Maximus quickly become the true stars of this Disney animation. Maximus, like Pascal, is a kind-hearted creature that believes in what is morally right and saves Ryder from execution. The plot comes to its climax when Pascal finally rids Rapunzel of Gothel. Any Disney animation would not be complete without its very own “Happily Ever After” and this film is no exception, as Rapunzel returns to her rightful place in the kingdom. This coming of age, feel-good family film celebrates how true love really does conquer all.

Above are contrasting stills from Tangled, the first taken from early in the film when Rapunzel captures Ryder and ties him to the chair. The second figure is taken from the much later in the film when Rapunzel and Ryder are setting out in the boat to watch the golden lanterns. For this next section of the article it is important to focus on the positioning of Pascal in both these figures. Notice how in the first image Rapunzel holds Pascal in the centre of the figure and compare this to Rapunzel’s treatment of Pascal in the second figure, he is at the end of the boat, barely visible in this second figure.

To ascribe human attributes to an animal creates a likeable character with the potential for comic moments. Disney uses anthropomorphic animal presences with the characters of Maximus and Pascal to do just that –to create characters that are likeable that the whole family can enjoy. However by attributing qualities that are essentially human, such as moral judgement, this displaces the true sense of the animal. In the process of Maximus and Pascal gaining human attributes, the animal characters lose their animal-ness. The audience no longer see the animal as simply an animal because they have been constructed to be so much more than that. In the process of the animal becoming anthropomorphised the reality of the animal is lost. As the magic of Disney comes to life so does this original animal presence as the audience is immersed into a film that produces an infinite amount of possibilities with the power of animation.

Where ever Rapunzel goes Pascal accompanies her. The pet is a comfort to the lost princess and he is the only thing in the world that belongs to her. Rapunzel’s ability to experience familiarity with Pascal reduces her anxieties and gives the girl confidence, as with any child that has an attachment to a toy. Rapunzel’s pet chameleon becomes the symbol for a transitional object that represents the development of Rapunzel’s coming of age. In figure 1 Rapunzel’s sole focus is Pascal as she holds him in the palm of her hand, looking directly at him and looking for comfort from him. She is speaking an elaborate conversation with him in figure 1, even though it is unclear if Rapunzel understands Pascal’s squeaky noises of a reply, she is able to use Pascal to express her own thoughts. Rapunzel gains a sense of domination whilst imagining Pascal possesses the human characteristic of speech. It is clear that Pascal has significance or meaning for Rapunzel and she believes that he is always protecting her. Pascal’s anthropomorphism is accentuated when he makes the moral judgement to trip up Gothel and rid her from the tower in order to save Rapunzel. But before all that, Pascal becomes an object that allows Rapunzel to escape the tower and explore the world around her. It is not Ryder that helps Rapunzel escape the tower, but Pascal. Once Rapunzel becomes interested in the world around her then she is able to focus less on Pascal as her main source of comfort. The positioning of Pascal in figure 2 emphasises this transition into adulthood on Rapunzel’s 18th birthday. Whilst Rapunzel sits at one end of the boat, Pascal is at the other, placing a distance between the pair. The contrasting spaces of interior and exterior represent Rapunzel’s development further. Whilst the exterior space in figure 2 reflects Rapunzel’s escape from the tower, it also suggests her escape from childhood and progression towards becoming a woman. This freedom is expressed through the contrast of light spaces in figures 1 and 2. With one solid light in figure 1 reflecting Rapunzel’s focus on Pascal, skip forward to figure 2 and the light is everywhere; Rapunzel is no longer focusing her attention on Pascal, but on the world. Animal presence is made to be transformative in animation as it is not a fixed object. ‘Tangled’ literally means to ‘mix up, to complicate or confuse’[i] and with the animal presence of Pascal, the imaginative quality Rapunzel instils into his character allows him to come to life as he becomes so much more than a chameleon.

The animal presence of Maximus with his dog-like behaviour is comic. Anthropomorphic animals such as Maximus make for many funny moments in the comedy because the “animal” inside the palace horse is exaggerated, such as his dog-like tracking abilities. Maximus experiences recognition from the audience for possessing these characteristics, and for being a horse, because many audience members like horses. The scene in which Rapunzel persuades Maximus to postpone the chase of Ryder, she attempts to praise him by saying, ‘Oh he’s nothing but a big sweetheart’ to which Maximus responds with numerous tail wags. In effect Maximus’ exaggerated actions become his own language. Maximus thinks like a human, understands humans and expresses his thoughts like a human would. Even though the horse is not physically human, when Maximus is tracking Ryder he cannot be seen as a threat to Ryder’s freedom, because the animal remains one of the most comic and light hearted characters in the film. Maximus’ personality is shown through his facial expression, one of the most comic being his pompous attitude. Maximus’ actions are always implied because he is unable to obtain clear expression of self through speech. The horse’s inability to express himself clearly creates a comic confusion that runs throughout the film. The major animal presences of Maximus and Pascal come to represent the film’s main genres because they are subjected to human desires. With Pascal representing Rapunzel coming of age and Maximus being at the centre for the majority of the comedy in the film, both animal presences are an integral part to the workings of this coming of age comedy. This kind of animal presence allows the animal characters to be comic and relatable for the whole family.

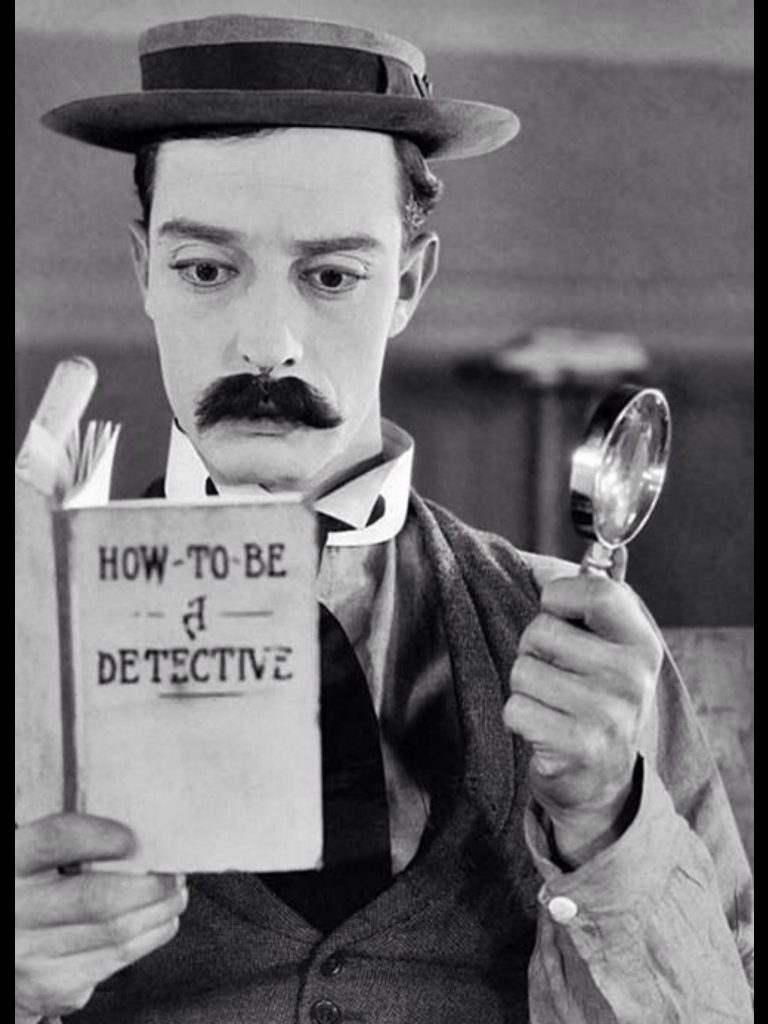

Since the animal characters are anthropomorphised, then surely it would make sense for the animals to also have the ability to speak. However after watching the silent animal characters on screen it is clear that the decision to hold back on animal human voice-overs establishes a greater quality of comedy. The animal representations in Tangled can be seen to have been inspired by the silent film era in which characters such as Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton became well known for their acting in silent comedy films. I have included a short film taken from the silent film era. Notice the similarities between Buster Keaton and Maximus. Even though neither character talks in their film, the comedy evidently runs throughout because of the relationship between the character and the audience. The silent film era, like the animal presences in Tangled, include a series of seemingly never ending comic mishaps. Take for example figures 3 and 4, both Keaton and Maximus are placed in the position of the detective. Whilst Keaton is seen to be reading a book entitled ‘How to be a Detective’, Maximus is eating a ‘Wanted’ poster of the criminal Ryder. The silent film protagonist forever remains on a futile journey that revolves around a series of comic events flowing into one another.

Disney embellishes silent film with animal presence with the constant focus being, as Buster Keaton believed, ‘When you’ve got spots in there where you can do things in action without dialogue, you should take advantage of it.’[i] (p.395) and Maximus and Pascal fill every scene to the brim with comic interludes. Even though the animal character may not always be involved in the central plot, it is the animal characters that constantly supply the film with laughter. The animal sidekicks do not talk, instead using facial expressions to communicate ideas. This was a central idea to silent film as Keaton said in an interview, ‘Let’s see how much material we can get where dialogue is not needed.’ [ii] The facial construction of the animated animal is central to the communication of emotion without speech. The eyes on Maximus are a typical example of this for they are not like a realistic horse. Animators construct the eye sockets towards the centre of Maximus’ face, like human eyes, to allow Maximus to communicate with his expressions more effectively. Similarly in silent film the protagonist relies on over animated facial expression to communicate thoughts. Pascal uses his whole body to express emotions with his colour changes. The chameleon is the embodiment of the silent film character because through colour he is able to successfully communicate any emotion he desires. Disney updates these stars of the silent film era with animals. It is not just about filling ‘spots’ as Keaton suggests, these animals unexpectedly become the true stars of this animation. The representation of silent animal presence is successful because their thoughts are always implied without them having to speak. The magic of the animal is never lost because it remains silent. The animal representations are at once realistic because the characters never speak, but unrealistic because the physical animated body of the animal is not a true representation of the animal in real life.

Tangled harkens back to the silent film era with the animals in film not talking and instead using their facial expressions to produce comedy. The concept of an animated horse sniffing the ground might seem to burst with originality, but when you’ve seen it once, you’ve seen it a hundred times. Everything that is good about Tangled – everything that is comic – is the belief that it is a fresh take on the fairytale classic of Rapunzel. Step forward 3 years to 2013 and Disney release Frozen, another musical animation. This film was a great success, smashing box office hits around the world. In the film the character Kristoff has a pet reindeer called Sven. I have included a teaser trailer that presents the comical characters of Sven and Olaf playing fetch with a carrot. There is a familiarity at work here between Maximus and Sven. Both the horse and the reindeer have been attributed the comic ability to behave like a dog, whether it be to play fetch or sniff the ground. In fact it is not just the animal presences that are similar, both the Tangled and Frozen plots are musicals about a lost princess returning to her kingdom. Study these similarities from a Marxist perspective and suddenly we can see, ‘how formalized the procedure is can be seen when the mechanically differentiated products prove to be all alike in the end.’[i] Ultimately a Disney animation film is a product to be sold to the paying masses. It is clear that once Disney have found a successful way of creating animal presence, they will follow a specific set of rules of plot and character construction to produce a successful film time and time again. When analysing an individual Disney animation it seems new and exciting for a film to place characteristics associated with a dog onto another animal. If the audience peel back the surface of a Disney animation then the cracks begin to show and all these seemingly unique qualities begin to be recognised as traits that are simply used to be monopolised on and the film slowly loses its sense of authenticity and originality. The capitalistic nature of the film industry is played out through the fact that the same animal presences are replicated over and over again. In this materialistic world that we live in, what is more superficial: the animal that behaves like a dog, or the audience that is satisfied with this presumably comic ideal? We are enslaved to consume the animal and spit back out a reproductive formulation to satisfy the paying masses.

Further Reading

Articles on Tangled and animals more generally include:

Brevet, Brad, ‘Movie Review: Tangled (2010)’, Comingsoon.net (2010) <https://www.comingsoon.net/movies/news/547939-movie-review-tangled-2010> [accessed 25 November 2015]

Carnevale, Rob, ‘Tangled – Glen Keane interview’, Indie London (2010) <https://www.indielondon.co.uk/Film-Review/tangled-glen-keane-interview> [accessed 25 November 2015]

Carnevale, Rob, ‘Tangled – Nathan Greno and Byron Howard interview’, Indie London (2010) <https://www.indielondon.co.uk/Film-Review/tangled-nathan-greno-and-byron-howard-interview> [accessed 25 November 2015]

Donofrio, Elaina C, ‘The Wonderful World of Gender Roles: A Look at Recent Disney Children’s Films’, eScholarship@BC (2013) <https://hdl.handle.net/2345/3061> [accessed 25 November 2015]

Leventi-Perez, Oana, ‘Disney’s Portrayal of Nonhuman Animals in Animated Films Between 2000 and 2010’, Georgia State University (2011) <https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/81> [accessed 25 November 2015]

Films that relate to similar animal presences include:

Frozen, as previously discussed, relates specifically to Tangled in many aspects. Frozen. Dir. Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee. Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2013.

The character of Flit in Pocahontas is a great comparison to Pascal’s role as a protective sidekick. Pocahontas. Dir. Mike Gabriel and Eric Goldberg. Buena Vista Pictures, 1995.

Rapunzel’s desire to “fly the nest” is also played out in Ratatouille with Remy the rat. Ratatouille. Dir. Brad Bird. Buena Vista Pictures Distribution, 2007.

The Princess and the Frog is a loose connection made by Flynn Ryder in the film with Rapunzel’s pet being a frog. The Princess and the Frog. Dir. Ron Clements and John Musker. Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2009.

YouTube videos relating to the making of Tangled include:

An interview with the supervising animator, Glen Keane, who was originally the animating director of Tangled, gives an idea of the challenges associated with the filmmaking process. Empire Magazine: ‘Glen Keane Talks Tangled’, YouTube (2011) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SM9Qadvc5kE> [accessed 25 November 2015]

For more information on the musical element running through Tangled the composer, Alan Menken, openly talks how musical creation informs the story of the film. Empire Magazine: ‘Alan Menken On Tangled’, YouTube (2011) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FCKm9_q0qc0> [accessed 25 November 2015]

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor and Horkheimer, Max, ‘The Culture Industry’ in Global Literary Theory, Ed. Richard Lane, (London: Routledge, 2013).

Feinstein, Herbert and Keaton, Buster, ‘Buster Keaton: An Interview’, The Massachusetts Review, 4.2 (1963), <https://www.jstor.org/stable/25079030> [accessed 16 November 2015]

Frozen. Dir. Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee. Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2013.

OED ‘tangled’ adj., 1. www.oed.com [accessed 21 November 2015]

Tangled. Dir. Nathan Greno and Byron Howard. Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2010.

Walt Disney Animation Studio: Disney, America, Inc., ‘Disney’s Frozen Teaser Trailer’, YouTube (2013) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S1x76DoACB8> [accessed 20 November 2015]

wonkat: Joseph M. Schenck, Metro Pictures Corporation, ‘”The Goat” – Buster Keaton SILENT COMEDY (1921)’, YouTube (2012) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fwls7oS-MHI> [accessed 20 November 2015]

[1] OED ‘tangled’ adj., 1. www.oed.com [accessed 21 November 2015]

[2] Herbert Feinstein and Buster Keaton, ‘Buster Keaton: An Interview’,The Massachusetts Review, 4.2 (1963), pp. 392-407 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/25079030> [accessed 16 November 2015].

[3] Herbert Feinstein and Buster Keaton, ‘Buster Keaton: An Interview’,The Massachusetts Review, 4.2 (1963), <https://www.jstor.org/stable/25079030> [accessed 16 November 2015] (p.395). All future references will refer to this edition and will appear in parenthesis to the text.

[4] Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, ‘The Culture Industry’ in Global Literary Theory, Ed. Richard Lane, (London: Routledge, 2013), p.332.