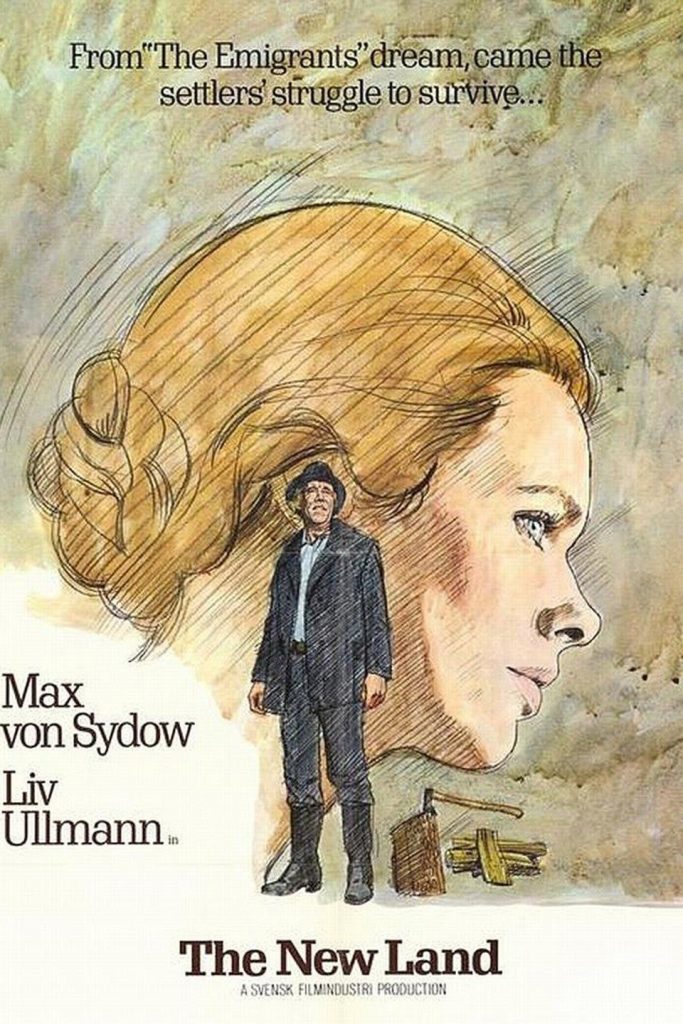

American expansionism and the frontier myth – the romanticisation of prosperity found in claiming the ‘wilderness’ and the forceful expansion of the American border – pillars of the Western genre [1]. From Jan Troell’s The New Land (1982), John Ford’s Wagon Master (1950) to Charlie Chaplin’s Gold Rush (1925); Western cinema has constantly glorified the rich opportunities which were found within the hardships and struggles of the frontier. Through romance, financial success or even a development in morality, the wilderness always seemed destined to provide for the new civilisation – regardless of those who had come before.

Yet what happens when nature acts against humanity’s control? When the pioneers and opportunists of the American West find themselves pushed out?

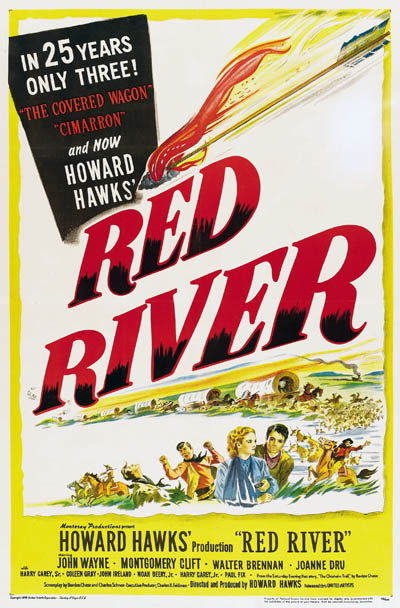

Howard Hawks’ Red River (1948) reimagines the frontier myth through a stampede of 10,000 cattle, united in their own community of solidarity, overrunning human spaces in a force which mirrors Dunson’s (the owner) attempt to forcefully expand his own territory – seen earlier as he steals cattle from a rival and rebrands them. What is most striking about this scene, is that the destruction caused by the animal society is due to a lack of human solidarity. While the cattle have been travelling as one, the men have argued among themselves, competing for gunslinger titles and personal ambitions. So, it is no surprise that the disastrous incident occurs after the mischievous Bunk Kenneally attempts to steal some sugar.

The scene opens as Kenneally reaches for the sugar. His eyes are fixed on his fellow cattle hands, wary of the punishment for being caught. The camera then cuts to Dunson – the first to react to a sudden, off screen clamour. Soon the rest of the men follow as Kenneally fails to hold back the displaced pots. As the intra-diegetic sound of falling metal ring out, there is a wide shot of the cattle beginning to stir [fig. 1]. The physical and psychological closeness of the animals is reflected through a domino affect, which starts at the far end of the herd, shuffling with unease until the rest begin to follow, reacting to each other’s mental state. At the centre of the herd are sleeping cows, adding a sense of familiarity and vulnerability to the family of animals – a civilisation in its own right by mass and solidarity. Furthermore, the varying levels displayed by the cattle claim a sense of individuality while maintaining this togetherness.

Two cattle hands preparing for a cattle drive, circa 1889. Credit: Jared Enos / Media Drum World

Though this shot mirrors the movement of the men, the unity between them is completely diminished. The scene progresses with several different close up shots of the cattle hands’ shocked expressions, and it is clear that Kenneally’s behaviour is perceived as both unacceptable and dangerous. The movement of the pots – starting from the top and escalating to the bottom – depicts a gradually worsening, unstoppable force. This places human failings at the same, if not greater, degree of risk as what is about to unfold. The frontier glorification of fighting the wilderness (or what colonial America perceived as wild) for peace has been disrupted as not only have the men failed to protect their group, but they have caused their own downfall and brought danger to themselves. It is their lack of alliance that is about to make the cattle’s act of complete solidarity so terrifying.

‘STAMPEDE!’

-Tom Dunson (John Wayne)

Suddenly, there is a burst of erratic, extra-diegetic composition and the deafening intra-diegetic sound of 40,000 hooves fill the night as Dunson declares ‘stampede!’. The cattle dominate the land with their singular presence, enhanced by the volume of the hooves and the lighting of the scene – a darkness that merges the animals together into a singular silhouette [fig. 2]. Human ownership and control begins to sever, with the dust almost concealing the presence of a cattle hand who is placed at the furthest distance from the camera, portraying him as a ghostly and forgotten figure [fig. 2]. While the cattle stampede, the men are no longer alive, no longer a strong enough force to seem like they are truly there – simply an apparition and a reminder of how the stampede came to be. The isolated figure, tall among the large black mass, looks on at the true animal civilisation of the frontier; a solidarity which the men failed to create through selfish incompetence.

As the stampede continues, an extreme long shot reveals the animals approaching a wagon, the only symbol of humanity left in their way, before cutting to a closer long shot as the wagon begins to break [fig. 3]. The use of mise en scène here creates a reversal in the frontier myth, as the ‘wilderness’ claim dominance over the land and force out the humans, tearing down what was before them. This is further emphasised as one of the men gets crushed in the stampede. The fast paced editing sees multiple different shots used in quick succession to portray his demise – from a close up of the man screaming to a level view of the upcoming cattle, a below view and then a wide shot from afar to highlight the lack of influence the humans have over their cattle.

‘They’re heading for the canyon!’, declares a cattle hand. A simple statement which highlights the true magnitude of the stampeding cattle; unable to direct the animals, the men have no choice but to chase

after the herd. In contrast to earlier in the film, it is no longer the humans who are leading the journey but the cattle.

Finally, the stampede comes to a stop. The camera cuts to an extreme long shot, displaying the canyon which physically bars the animals from going any further [fig. 4] – emblematic of the end of the frontier. They have finally settled and the previously erratic extra-diegetic composition becomes grandeur with the sound of percussions. Their unanimous decision to head into the canyon for safety is unplanned and instinctive, as is their sense of herding and solidarity. This, is what truly strikes against the frontier myth of American expansionism. What’s ‘wild’ will always be together, and so attempting to impose control as a group of humans – whose desires are fiercely independent – will cause damage and destruction. The cattle have usurped the human frontier myth, that the men of the west can claim the wilderness and natural state of lands (owned by others) as their own, forcing their own animal civilisation upon them.

[1] Carter, Matthew, Myth of the Western : New Perspectives on Hollywood’s Frontier Narrative (Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press, 2014)