Is this love, is this love, is this love, is this love that I’m feelin?

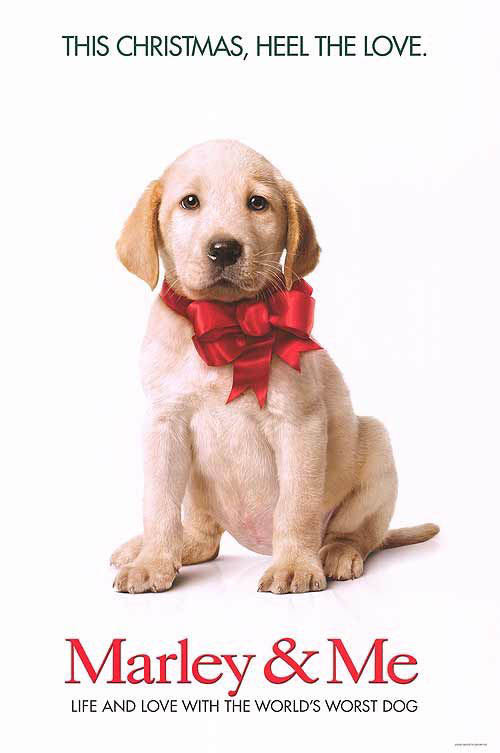

This is the one question undoubtedly playing on John Grogan’s mind when looking at his cushion shredding, underwear stealing, jewellery eating, chaos causing canine; an ebullient bundle of joy whom he later asserts is “the world’s worst dog.” It goes without saying that unruly Marley, despite his many flaws (emphasis on the many), brings countless smiles to people’s faces and warms hearts aplenty.

When Jenny and John make a life changing decision to start a family after marrying, little does Jenny know that John has doubts about taking on paternal responsibilities. They’ve moved down South to begin a new life in Florida and having already checked “new house” and “new careers” off of their generic family list; having children being the next empty box. After confessing concerns to his friend and work colleague about embracing the transformation from manhood to fatherhood, John resolves to delay any chances of immediate pregnancy with one simple solution; cue boisterous ball of yellow fur accompanied by full frontal face licks of affection.

In order to replicate the experience of having a child and henceforth subdue Jenny’s maternal instincts, John adopts Marley. This centralises the moral issue regarding buying and domesticating animals for human happiness and companionship. Realistically, Marley does not represent the couples future child, he is in fact a replica of the child within John. Wilson is part labrador. Their golden locks of hair being uncannily similar reinforces this theory entirely. The fact John turns to such drastic measures rather than talking to Jenny about his worries in the first place offers further support of an attempt to cling on to his own childhood. The transitional process of John starting as an unruly man to becoming a fully integrated, domesticated father is mirrored in Marley’s animal presence. The Marley as Grogan aspect of the film is significant in that it serves as a caustic commentary on man’s domineering disposition in containing an animal within the home.

The animal-honoured domesticity of having a pet is depicted in social accordance to the cultural constructs of the family film genre. Despite it somehow seeming natural in the Grogan household; life with dogs does not happily and straightforwardly ensure human success stories, i.e. creating a newspaper column based on said “world’s worst dog” and consequentially receiving a larger income. A reflection on the film in accordance to this idealist view can be found in the review by Peter Bradshaw, who reduces “blond, bland” Wilson’s performance to fifteen years of “marital crisis, career hangups [and] daddy issues.”Human life is simplified in particular ways in order to secure the audience’s homely family fantasy, and in most instances it does just that.

Before they know it, Marley grows into a considerably larger, accident prone mischief who turns their new home into what looks like a war zone. Anything and everything starts to revolve around him and the Grogans make all sorts of adjustments to squeeze in their new pup’s demands and requirements; including a 50% salary income cut on behalf of Jenny, who opts to be a stay at home Mum. It dawns upon them that they may have possibly taken on more than they can chew, unlike Marley who consumes pretty much everything.

Marley getting expelled from obedience school, and John finding this amusing, again clarifies the “fatuous stereotyping” Bradshaw comments upon. Marley appears to verge on mentally insane – note stolen Thanksgiving turkey – and while he imbues personality into the film, with his voracious antics becoming the main source of enjoyment, the fast-paced action and themes evoked throughout are familiar of generic dog movies. David Frankel tries to stray away from generic conventions by interspersing the years of tackling unruly freedom, in relation to both Grogan and Marley/man and animal, with episodes of tender family bonding. Marley becoming a cherished member of the family and teaching the Grogans the true concepts of unfaltering loyalty is entirely heartwarming, yet Frankel is essentially abiding by the idealistic utopian quality needed for a successful family film.

The stock types which make up the cast identify with the universal themes of marriage, love and family. Jennifer Aniston who plays Jenny reflects “You think it’s a story about a mischievous dog – and it is – but it’s so much more than that. There’s something about the Grogans and about Marley that connects in a universal way.” However, the manipulation of sentiment for melodrama’s sake needs to be taken into account in this dog focused film. Marley is able to support Jenny when John fails to do so and the scene in which Marley comforts her after she returns home from the hospital having just had a miscarriage is one of the most moving in the film. Marley is explicitly presented as an externalisation of Grogan’s untamed, self-centred masculine role. The way that Marley stops misbehaving to adapt to the needs of his human owner’s emotions creates a fantasy vision about the correct socialisation of men. When Jenny falls pregnant again and successfully brings a new baby into their world, Marley surprises them both, again, by adopting an incredibly protective parental-role himself and handles the children with the utmost care. The emotional work enforced on Marley due to John’s lack of support suggests that dogs are perfectly secondary to proper human monogamy, yet in the film they are not.

Throughout his entire presence in the film, Marley teaches the Grogans various life lessons. He not only shows them the strength and importance of love and how this does not falter over time, but also how dogs have a reciprocal love for humankind. This supports what McFarland asserts in saying that there are “differences and similarities we humans share with other species,” yet his canine presence also raises concerns regarding pet-keeping. Grogan, albeit not in a criminal sense, essentially exploits his pet to gain income and this makes viewers question whether it is a pay rise or true love which makes the companionship between Marley and John surpass that of a normal man/dog bond. This poses the question- can a companionship be formed between a human and animal when an animal cannot consent to anything? The domestication of animals re-enforces the selfish desire of human beings to possess and command other species, and in this instance many of Marley’s natural desires and behaviours are repressed.

Chief among the trials and tribulations caused by rambunctious Marley, is the attempt to tame him at obedience school. The sergeant like instructor, Ms. Kornblut, proudly tells the Grogans that no dog has ever failed her program. Marley’s determination to remain a wild and free spirited dog highlights how dogs have certain drives despite being confined to a human home. Rather than blaming the dogs for their bad behaviour, Ms Kornblut insists that there are only bad dog-owners, and proceeds to berate the Grogans throughout the class. Until they are politely invited to leave that is. Marley’s disobedience shows that you cannot control all aspects of family life and neither can you fully domesticate animals for convenience. This scene undercuts the attempt by Frankel to sell us a picture of the perfect nuclear family.

Marley and Me is a family film in the stereotypical sense; it is based upon the Grogan’s family life. The familiar quality of having a pet and starting life as a newly wed couple, whilst shown in a chaotic and haphazard sense, is explored under aesthetically bias lighting. The growth of Marley from puppy to adult is paralleled to the growth of John; they each mature in time. The film adheres to the genre in many ways and Frankel particularly highlights the fun that is to be found in marriage, which is not typically portrayed in Hollywood films. It is often the concept of everything going downhill that is focused on, whereas in Marley and Me this is not the case. Frankel points out that “the story tells us how important a dog’s perspective can be to us – and specifically to the Grogans. Dogs are wonderful because they don’t think about the future or the past; they know only the joy of living in the present. And humans, sadly, often forget that.” He concludes that Marley is a “beautiful metaphor for happiness.” (Levy, Cinema 24/7, 2008) The repetition of Marley running through the back door screen on multiple occasions and at different ages in his life exemplifies this quality perfectly. However, there are slight imperfections in this metaphorical vision of happiness in that there are no explorations of Jenny’s self development. The ‘ideal’ mother is shown quitting her job, despite being the better reporter out of the two, as an act of self-sacrifice for her family.

The conclusion focuses solely on the heartbreaking consideration that as Marley is dying, so too is John’s child-like freedom. The emotional ending, in which John is forced to make the decision to put Marley to sleep for ethical reasons, falls appropriately into the genre of drama whilst tying in with the biggest problem involved in pet-keeping. John, as the main character, is in conflict at this crucial moment of his life and this conflict regards both himself, of course, and the family unit. The loss of Marley highlights how pet-owners take control over animals. Not only do humans declaw dogs, neuter dogs, and take them to obedience classes, they also euthanise them too. This concept is brushed over to focus on the heightened sentiments of John, which again gravitates towards greater human significance.

There are many family films which present animals as being secondary, and consequentially subject to, human desires in the chain of existence. In We Bought a Zoo, the concept of pet-keeping is a lot broader in the sense it focuses on caged animals in a zoo, rather than a singular “free” animal in a house. The tigers death being delayed due to Benjamin Mee’s emotional and financial instability is dimmed by the heroic sacrificing of him having given up his job to raise his broken apart family amidst the fantasy based landscape at Rosemoor Wildlife Park. Animals are instead shown, similarly to in Marley and Me, as being subjects to human emotional dependance.

Further Reading

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/filmreviews/4980274/Marley-and-Me-film-review.html

https://www.clickertraining.com/node/1830

https://www.humanehollywood.org/index.php/movie-archive/item/marley-and-me

Bibliography

Bradshaw, Peter, ‘Marley & Me’ The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/mar/13/marley-and-me-film-review [accessed 17 December 2015]

Dirks, Tim, AMC Filmsite ‘Comedy Films’ Part One https://www.filmsite.org/comedyfilms.html [accessed 15 November 2015]

Dirks, Tim, AMC Filmsite ‘Drama Films’ https://www.filmsite.org/dramafilms.html [accessed 15 November 2015]

Levy, Emanuel, ‘Marley & Me: Interview with Director Frankel and Stars Wilson and Aniston’ Cinema 24/7 (2008) https://emanuellevy.com/comment/marley-me-interview-with-director-frankel-and-stars-wilson-and-aniston-7/ [accessed 18 November 2015]

‘Marley and Me’ Production Notes (2015) https://www.cinemareview.com/production.asp?prodid=5153 [accessed 20 November 2015]

Sarah E. McFarland, ‘The Animal as verb: Liberating the Subject of Animal Studies’, JAC, vol.30, no.31, (2010) pp813-823), p.816

Waal, Frans de, ‘Sympathy’ The Age of Empathy: Nature’s Lessons for a Kinder Society https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=qT04AAAAQBAJ&pg=PT86&lpg=PT86&dq=marley+comforts+jenny+after+miscarraige&source=bl&ots=Tg8ESN5D23&sig=SFcnUVytihPQ_–WlkF1QbMYYlc&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjBpszHraHJAhWBXRQKHXgYDuEQ6AEITTAI#v=onepage&q=marley%20comforts%20jenny%20after%20miscarraige&f=false [accessed 19 November 2015]