What was up with the deer?

Sam Esmail’s Leave the World Behind (2023) is an apocalyptic psychological thriller. Conventional American family, the Sandford’s, attempt to disconnect from the city with a family holiday. Presented with an opportunity engage with nature, the family remains obsessed with their gadgetry. When they are plunged into technological darkness, almost crushed by an oil tanker, stalked by hundreds of deer, with flamingos landing in their swimming pool, they are left to their own devices. The sudden collapse of their world resembles religious apocalypse, and the recent pandemic. The character’s failure to connect with the animals around them, parallels the abandonment of animals within post-pandemic society. The film is disorienting, tense and ripe with cultural references to the current sociopolitical climate, yet one superseding question plagued the minds of viewers: what was up with the deer?

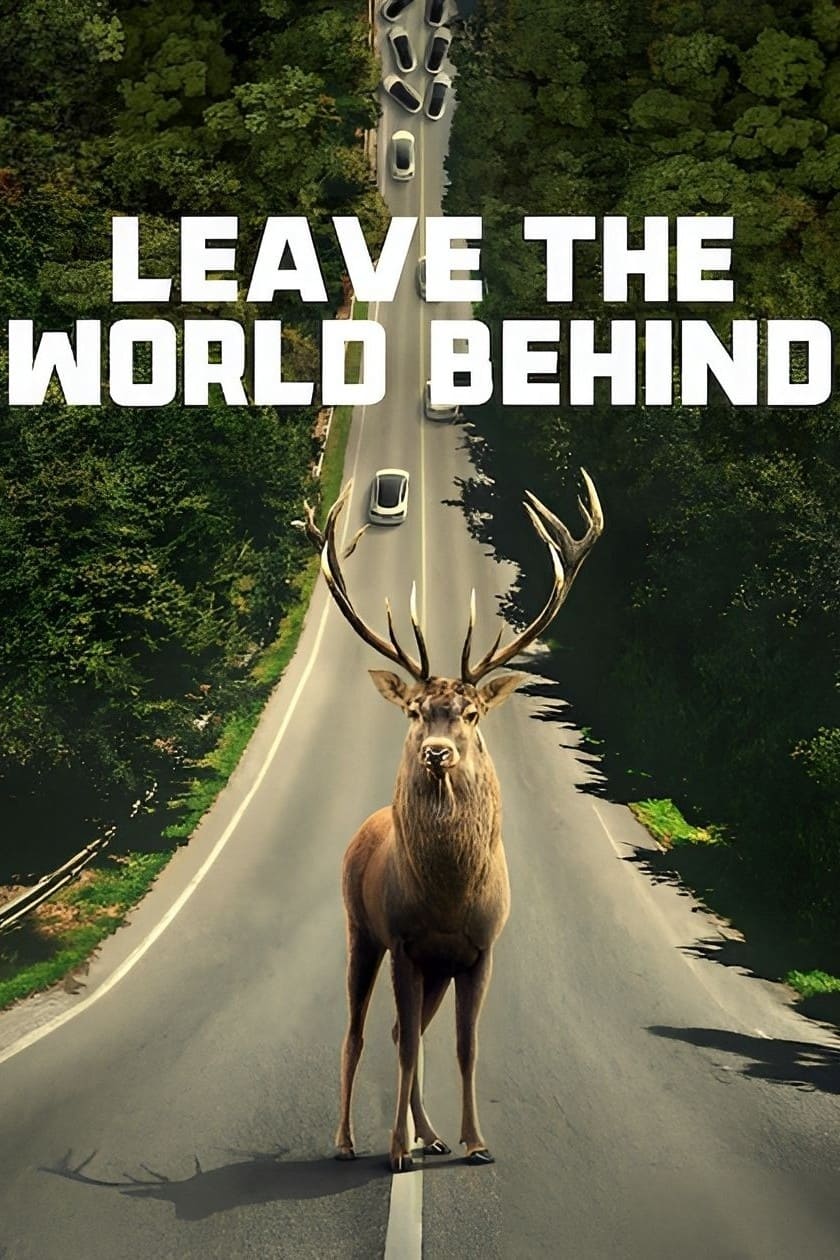

The image of the deer, specifically the stag, is present in all advertising and is a significant motif throughout the film. In promoting the film, Netflix placed mechanical deer in public areas of cities in America. People responded by taking photos and videos and sharing them online, proving that humans are terminally attached to technology.

As an apocalyptic psychological thriller, the presence of the deer is warped and ominous, signified by the disturbing musical score that accompanies their arrival onscreen. Typically, in film and in real life, deer are represented as regal and docile, Esmail ‘turn[s] that sweet image into this sort of ominous, menacing, almost warning.’1 The stag, being the ultimate symbol of the natural world, is the central motif of the film, he consistently leads the herd to the Sandfords.

The deer’s attempts to warn the family, and the family’s ignorance/ aggression towards them, demonstrates that humans and animals are ultimately disconnected beings. The gaze between human and animal is permanently severed, and the cause of this is human reliance on technology and their subsequent isolation from the natural environment. This apocalyptic narrative parallels the human-animal relations that came into discussion during the Covid-19 pandemic, which were dropped when restrictions were lifted, and human life resumed. It also rejects religious stories that present humans as connected to the natural world.

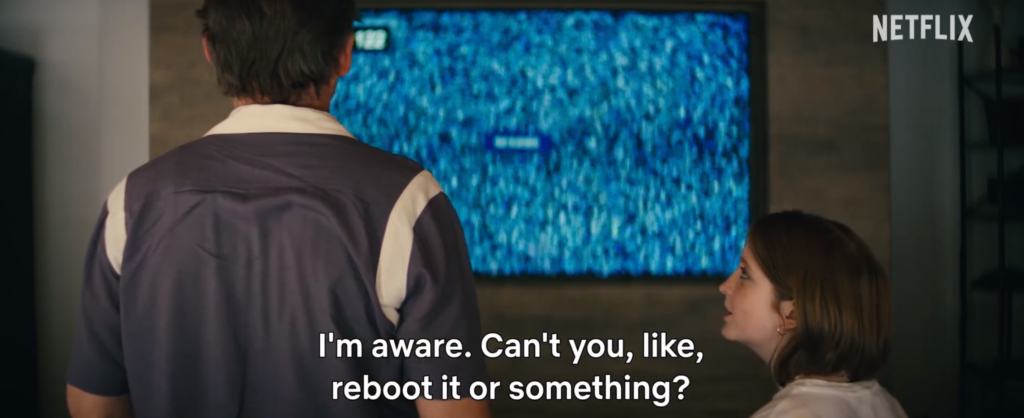

The youngest Sandford, Rose, is the first character to acknowledge the oddness of the deer. This is foreshadowed at the beginning of the film, when they depart the homogenous cityscape, and the rural mise-en-scene of greenery emerges. The camera pans and zooms in on the characters individually, showing that all members of the family remain connected to technology. Amanda talks on the phone, Clay fiddles with the touchscreen of the car, Archie plays a violent game on his phone, and Rose tries to watch Netflix. She is the first character to become disconnected from technology.

The deer-encounter scene is triggered by Rose becoming frustrated that the Television is still not working, causing her to storm outside. This directly links Rose’s disconnect from technology to her potential connection to the natural environment. The fact Rose is the youngest character, and female, is also significant. In an apocalyptic scenario, Rose represents the next generation, and her gender would facilitate repopulation and the survival of the human race. Even her botanical name symbolises her potential to connect with the natural world.

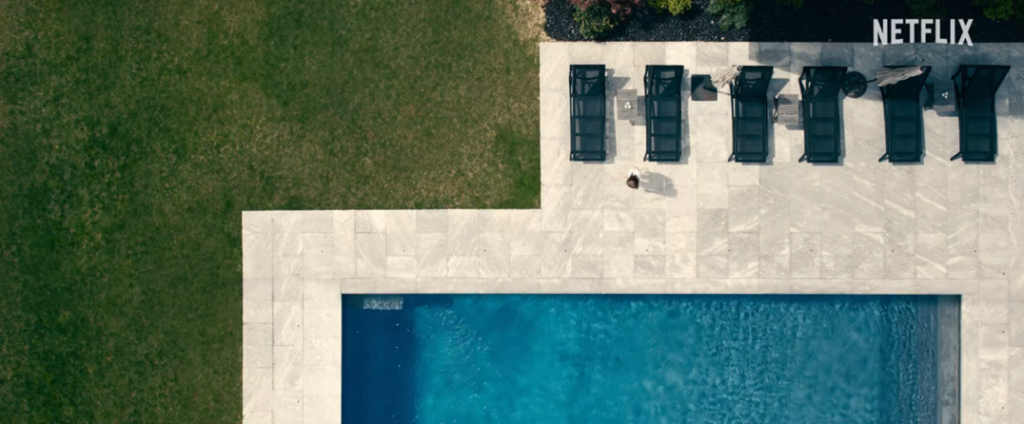

At the beginning of the scene, Rose is pictured from an aerial view, which literally captures the line between man and nature. The grass meets the stone in a zig-zag pattern, which demonstrates the separation of the two worlds, but also their invasion of each other. Rose notices the deer and walks toward them cautiously. The camera focuses on her bare feet in the grass as they breach the border between man and nature, signifying her potential connection to the natural environment. Her bare skin against the grass creates a harmonious, natural mise-en-scene, which evokes images of Eve in the garden of Eden, further exaggerating Rose’s importance in the survival and repopulation of the human race, and her potential connection to the natural world.

The camera zooms in on Rose’s face, staring at the deer, then the camera faces the deer and pans upwards and outwards, revealing hundreds of deer beyond the treeline. The diegetic soundtrack is gradually replaced by a building, non-diegetic musical score which swells as the camera pans. The atmosphere becomes ominous, foreshadowing the pessimistic tone of the rest of the film, and as Rose is cut out of frame, this foreshadows the human-animal disconnect.

This event prompts Rose to ask her older brother about the deer, “This morning I saw deer. Not a deer. A fuck lot of deer. A hundred, maybe more, right in the backyard. It was really weird, Archie. Do they go around in big groups like that?” Archie’s response mirrors the other character’s ignorance and aggression towards the deer: “Why the fuck would I know anything about deer?”2 For example, the next deer run-in happens to characters Amanda and Ruth. Before they encounter the deer, Amanda, who ‘fucking hates people,’3 monologues about the selfishness of the human species.

“We fuck every living thing on this planet over and think it’ll be fine because we use paper straws and order the free-range chicken. And the sick thing is, I think deep down we know we’re not fooling anyone. I think we know we’re living a lie. An agreed upon mass delusion to help us ignore and keep ignoring how awful we really are.”- Julia Roberts as Amanda Sandford

Figure 15: Amanda Sanford’s speech

Following this, a large herd of deer approach the women, the stag leading the herd. This scene occurs in conjunction with the male characters of the film seeking medication for Archie, whose teeth are falling out after being bitten by a tick. As the male characters argue with a doomsday prepper and guns are pulled, the women are surrounded by deer, and the tension builds. The non-diegetic musical score imitates drone-like buzzing, and the atmosphere becomes incredibly volatile. Amanda screams and violently waves her arms at the deer, causing the deer to scatter.

This happens as the men’s argument results in threatened gun violence, emphasising the human tendency to respond to fear with violence and panic. The deer are trying to warn Ruth and Amanda, but their communication is futile. This demonstrates the disconnect between humans and animals, particularly in regard to the older characters, which leaves all hope resting on Rose’s shoulders. The speech Amanda gives throws a shadow of irony over this interaction, because it immediately proves her point, that the disconnect between human and animals has become too great to overcome. Amanda’s hypocritical environmental pessimism, mirrors human-animal relations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2020, memes began to go viral surrounding the lockdown’s effects on nature, stating that ‘humanity is the virus.’4 People posted images of animals with the caption ‘nature is healing.’5 This widespread awareness of how humans negatively affect the environment and animals triggered a parody, mocking this sentiment. Despite the satirical nature of the posts, there is some truth behind them. This time period labelled the ‘Anthro-pause,’6 saw better air quality and less pollution. In turn, animals began to turn up in unusual places. For example, buffalo on a main road in India.

The apocalyptic overtones, detachment from daily life, and presence of animals in strange places, parallels the narrative of Leave the World Behind. This is not surprising, considering the book that the film is adapted from was published in 2020. So, considering this, Amanda’s speech echoes the misanthropist sentiment of online discourse during the pandemic.

When lockdown restrictions were lifted and human life resumed, so did the climate crisis. In Leave the World Behind, Rose symbolises the last opportunity for humans to connect with nature and survive beyond the severance from technology. From the point of her first interaction with the deer, Rose becomes fixated on finding them again. She expresses her anxiety to her mother through a story about a man, who prays to God to save him from a flood, but ignores all the signs God sent him and dies. This further portrays Rose as the saviour of humanity, and she leaves to find the deer. The film saves what she finds till the very last moment, building suspense as we wonder if she is successful. In the meantime, we follow Ruth and Amanda searching for Rose frantically. In doing so, Ruth, although too late, finally realises that the animals were trying to warn them. Just as she realises this, a horrific truth is revealed…

“I saw flamingos in the pool last night…The animals, they’re trying to warn us…They know something, they know something that we don’t…It’s like when dogs know storms are coming.” – Myha’la Herrold as Ruth Scott

Figure 23: Quote from Ruth

In this landscape shot, the city and the forest is divided by the lake, which exemplifies, firstly, the separation of the human, urban world and the natural, rural world. Secondly, this demonstrates how the apocalypse will wipe out humanity, but the natural world will survive. So, if the Sandfords are able to connect with nature and the animals, they could survive, and if not, they too will be doomed. The film ends with Rose, who comes across the house next door. This is foreshadowed earlier on in the film, when Rose sees the stag, stood in front of the house, the stag then runs out of frame, leaving just the view of the house. This is significant because the film ends with Rose finding the ‘rich asshole doomsday bunker,’7 in this house, where she turns the TV on, and watches the last episode of Friends. The choice is presented to Rose clearly, the stag or the house, the stag represents the natural world, the house represents anthropological technology. Rose chooses the house.

Despite finding a bunker, which will ensure temporary survival, this ending condemns humanity, because it solidifies the permanent severance of the human-animal connection. Rose smiles, gazing at the television, which demonstrates that the human gaze is unchangeably fixed on technology. In addition, the cold, blue, artificial light contrasts scenes where Rose gazes at the deer, wherein the lighting is warm and natural, further assuring the severance. This confirms that ‘the look between animal and man[…] has been extinguished,’8 and replaced by the look between man and technology.

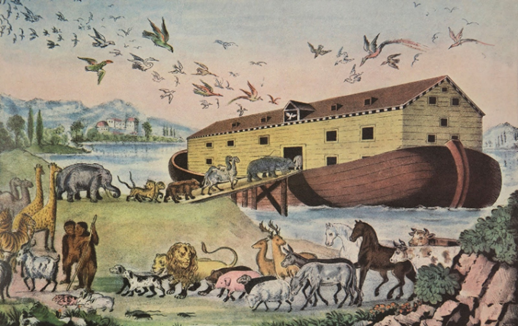

As Esmail states, the deer ‘represent this idea of nature, as a warning sign about what we’re going through, and how our tech is blinding us to it.’9 This mirrors the warning signs that animals displayed during the pandemic, which have also been ignored. The apocalyptic theme of the film, combined with the few religious references, echoes the story of Noah’s ark. However, wherein Noah and his family were saved alongside the animals, Rose and the Sandfords, are on their own.

To conclude, Leave the World Behind uses the image of the deer, and other animals such as flamingos and geese, to demonstrate that in the event of a genesis-like apocalypse, humans are doomed. This is due to the irreparable disconnect between humans and animals, the gaze ‘between man and nature [is] broken.’10 This film utilises human-animal relations that were questioned during the pandemic, a real apocalyptic event. Ironically, though this film criticises human reliance on technology, none of the animals in this film are real, ‘they are all digital.’11 The animals are CGI, the deer in the advertising are mechanical. In this way, Leave the World Behind is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

- Jack King, ‘All of your spoiler-y questions about Leave the World Behind, answered by its director’, GQ (8 December 2023) https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/leave-the-world-netflix-director-interview-2023 [Accessed 15 January 2024] ↩︎

- Leave the World Behind, Sam Esmail, (Netflix, 2023) [Accessed 17 January 2024] 00:57:11 ↩︎

- Ibid., 00:03:17 ↩︎

- Kate Yoder, ‘Why ‘Nature Is Healing’ Might Be the Best Pandemic Meme’, Atlas Obscura (14 July 2020) ) < https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/nature-is-healing-covid-meme> [Accessed 15 January 2024] ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Leave the World Behind, 01:57:42 ↩︎

- John Berger, ‘Why Zoos Disappoint’, New Society 21 April 1977, p.123 ↩︎

- Jack King, ‘All of your spoiler-y questions about Leave the World Behind, answered by its director’, GQ ↩︎

- John Berger, ‘Animals as Metaphor’, New Society 10 March 1977, p.504 ↩︎

- Jack King, ‘All of your spoiler-y questions about Leave the World Behind, answered by its director’ ↩︎

Bibliography

Primary sources

Leave the World Behind, Dir. Sam Esmail (Netflix, 2023)

Secondary sources

Berger, John, ‘Animals as Metaphor’, New Society (10 March 1977), pp.504-505

Berger, John, ‘Why Zoos Disappoint’, New Society (21 April 1977), pp. 122-123

King, Jack, ‘All of your spoiler-y questions about Leave the World Behind, answered by its director’, GQ (8 December 2023) <https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/leave-the-world-netflix-director-interview-2023> [Accessed 15 January 2024]

Yoder, Kate, ‘Why ‘Nature Is Healing’ Might Be the Best Pandemic Meme’, Atlas Obscura (14 July 2020) < https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/nature-is-healing-covid-meme> [Accessed 15 January 2024]

Further reading:

Arora. Shefali, Deoli Bhaukhandi. Kanchan, and Kumar Mishrac. Pankaj, ‘Coronavirus lockdown helped the environment to bounce back’, National Library of Medicine (29 June 2020) < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7323667/> [Accessed 10 January 2024]

Kinver, Mark, ‘Then and now: Pandemic clears the air’, BBC News (1 June 2021) <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-57149747> [Accessed 12 January 2024]

Leave the World Behind (2023) directed by Sam Esmail • Reviews, film + cast • Letterboxd

Prasad, Sumith, ‘What is the Significance of the Deer in Leave the World Behind? Theories’, The Cinemaholic (8 December 2023) < https://thecinemaholic.com/leave-the-world-behind-the-deer/> [Accessed 16 January 2024]