Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part I (2011) is the penultimate film in the franchise. Harry, Ron and Hermione begin a desperate race to understand the instructions Dumbledore leaves after his death, concluding they must find and destroy the horcruxes that keep Voldemort alive before he discovers their quest. The horcruxes are objects containing a part of Voldemort’s soul, which he has divided into seven pieces in a bid to be all powerful through immortality. The magical narrative, core conflict of good versus evil, and other-worldly setting means the film belongs to the fantasy genre. Yet, despite the fantastical genre, the film makes regular comments upon very real societal notions. The film’s audience is made up of a wide range of ages, genders and backgrounds and the franchise’s popularity has cemented its status as a timeless classic.

On second thoughts, timeless *may* be a stretch. Sorry JK Rowling.

Unquestionably, the narrative relies upon a hero and villain – the two lead masculine characters. At the side of each male figure are Voldemort’s reptilian aid, Nagini, and Harry’s doting owl, Hedwig, who are both female. Nagini is a female python-like snake. For those avid Potterheads, some may be aware of the snake’s past as a woman bound by a genetic ‘maledictus’ – a blood curse which eventually causes irreversible animal form. Ultimately, Nagini is Voldemort’s most trusted confidant and the audience attribute the snake and her master with equal villainy. Snakes are typically equated with evil, deceit and danger; a framework reinforced through common insults in everyday language and dark representation of the animal in TV and film. On the contrary, Hedwig is a female snowy owl and Harry’s closest companion since childhood. She valiantly sacrifices herself in a battle after diving in front of a spell aimed at Harry, saving his life. The female animals are symbolic of the binary of good and evil, and this relies upon the cultural response to the two animals in order to be successful. As female sidekicks, the demonised snake and the gentle owl typically conjure a parallel response of loathing versus admiration. I believe the animals also portray a patriarchal binary of femininity – with vulnerable, pure and fragile being attributed to the side of good, leaving an array of characteristics cast to the side of evil. Thus, I will explore how the film reinforces not only the discourse of species, but also the patriarchal view of femininity, using Hedwig and Nagini.

Figure Two – Nagini’s lost ability to freely transform, in a scene from Fantastic Beasts: Crimes of Grindlewald.

Figure Three – Harry and Hedwig.

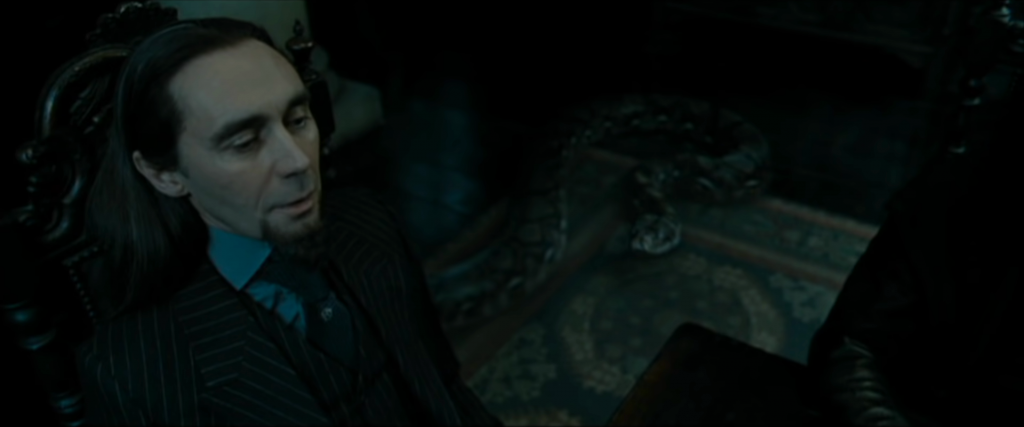

The film reiterates snakes being a fear stimulus by showcasing Nagini’s notoriety through several repeated horror techniques used in her moments on screen. In the opening scene of the film, Voldemort, Nagini and a collection of death eaters meet at Malfoy Manor to discuss their next move in finding Harry Potter. The film harbours a contextual sense of darkness, in the increasing danger and widening impact of Harry and Voldemort’s feud within the world of magic. This is mirrored by the monochromatic colour scheme consistent throughout the film. This is a stylistic feature that is commonly used in horror, as an indication of a setting devoid of hope. The colour tone is displayed to an audience for the first time as Voldemort and his disciples scheme for the downfall of Harry, suggesting the darkness arrives and lives within these characters.

As conversation begins, Voldemort’s attention turns to Pius – a cowardly informant from the Ministry of Magic. The frame below is a medium close-up shot on a wide lens. The shot is of shallow focus, depicting Nagini blurred in the back of the frame as a reminder of the threat he faces if his words are deemed disagreeable. The camera is angled from a raised perspective creating a high-angled shot, emphasising Pius’ inferior, prey-like vulnerability. As Pius speaks, an audience hears the subtle diegetic sound of Nagini’s gentle hiss and her skin’s friction upon the floor. Whilst Pius is in closer proximity to the camera and so appears larger, the unsettling noise and her striking position serves as a symbol of her superiority over a man who cannot look in her direction.

Voldemort’s attention then turns to their dinner guest. Charity Burbage is a former teacher at Hogwarts, disturbingly floating above the table. Voldemort suddenly casts his wand, her lifeless body slams on the table, and Voldemort exclaims, “Nagini, dinner”. The mise-en-scene here exemplifies Nagini’s status as powerful and predatory. Yates uses a close-up tracking shot as Nagini slithers menacingly down the central spine of the table towards her victim. As the dolly moves down, the wide lens reveals the reactions of the characters along the side of the frame. The reactions of horror reinforce the alienation of Nagini, as a creature a fraction too disturbing even to the comparison of Voldemort. In the final moments of the shot, Nagini bares her fangs and lunges for the lens as the non-diegetic sound reaches a climax in speed and pitch, parallel to the peak of tension elicited in audience members.

The stereotypical societal opinion of snakes, particularly in film, is epitomised through the portrayal of Nagini’s character in this scene. She not only evokes fear in other characters, but an audience perceives her as aggressive and dangerous through her unsettling movements and unpredictable character. When considering the factors of animality that evoke fear, the bodily appearance of the animal, for example, “an unusual body shape which could stand for otherness”, is a common contribution to a reaction of anxiety.1 The film and its portrayal of Nagini both relies upon and reinforces this type of reaction. The discourse of species is a term addressing the social framework of ideas surrounding different animals. It is made up of terms, attributes and emotions that relate to animality but do not necessarily accurately reflect the animal from which they are derived. Animal portrayals in film often characterise creatures with human affections, like a snake defined by its spiteful nature in the case of Nagini. Yet, these portrayals of anthropomorphism often leave a permanent stain upon the audience’s future perception of the animal in real world applications. Despite Nagini being a 3D animation, the film experience manifests in viewers as “prejudice-based fear”.2 There is a sense of otherness embedded within Nagini’s snake form; an otherness sculpted through the fear of those around her. This is easily comparable to perception of female identity as antagonistic if non-conforming to patriarchal ideals of submission and vulnerability. Nagini’s unruliness ultimately means her female identity enters a space of undesirability. The film’s incorporation of her as a female and as a snake combines to illustrate the binary in femininity – a binary exemplified by Hedwig.

The character portrayal of Hedwig is a polar opposite to Nagini. When comparing both portrayals of the animals, their division into agents of moral opposition rather than simply different animals is defined by their appearance. Hedwig is a pure white, fluffy bird with the ability to fly. Contrastingly, Nagini is a slithering, darkly coloured, scaly reptile. An animal’s method of movement is critical to the manner in which it is perceived, with a study published in the International Journal of Science Education concluding that “flying in the air versus crawling on the ground was a major differentiator for attitude” towards animals, with flying animals being considered “pleasant and confidence-inspiring”.3 The antithetical reactions elicited by Hedwig and Nagini’s appearance are ideal to encompass the conflict of good versus evil parallel to Harry and Voldemort, and even more fitting to subtly align the desirable attributes of femininity with the favoured female animal.

In addition, the religious connotations of the two animals’ appearance must be acknowledged. Without being too cliche, Hedwig is undoubtedly an angelic symbol. Her feathers are white – an obvious expression of purity and virtue. In terms of femininity, the colour white is traditionally worn as an indication of virginal purity, which is a further reiteration of patriarchal gender standards through the favour of Hedwig over Nagini. Adding to this, birds are considered an emblem of fragility in their stature, and women of the desirable patriarchal mould are naturally vulnerable and fragile creatures. Gross, I know.

In stark contrast, religious tales do not favour poor old snakes. The story of creation in the Garden of Eden is an archaic example of snakes representing the devil, sexual desire and the temptation of succumbing to such feelings. Considering the religious connotations and the sense of temptation integral to serpents in the Bible, Nagini’s internal characteristics can thus be aligned with a ‘femme fatale’ – a woman deemed dangerous in her ability to reverse the binary and be empowered by the parts of her femininity that the patriarchy shames. Most crucially though, a ‘femme fatale’ is a woman with the power to lure and deceive, epitomised by Nagini’s bodily possession of Bathilda Bagshot.

Within the scene, Yates’ favour of typical horror methods resurfaces in Nagini’s magical possession of Bathilda, an elderly witch. Nagini’s presence is completely unknown. As Harry follows Bathilda upstairs, Hermione is left behind to explore the rest of the house with trepidation. A sense of audience tension is built using cuts between Harry and Hermione paired with a slowly increasing regularity of the cuts between each shot. This method exaggerates the sense of impending danger within the scene, as if Hermione may discover something that will reveal the danger Harry is in.

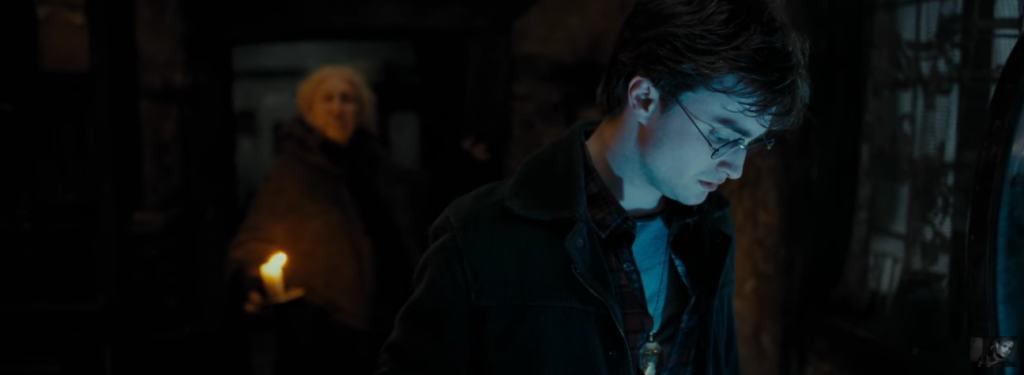

Figure Seven depicts light design within the scene as symbolism of the opposing forces of good and evil at play. For example, in the frame above, Harry and Bathilda’s faces are illuminated by a flame and a wand. The cool, crisp light of Harry’s wand and the warm light of the flame demonstrates how the practical lighting is used to illustrate a contrast – a contrast that indicates a difference between the characters, reiterating the narrative of good and evil. Here, Yates repeats his use of the shallow focus in a medium shot with a wider lens as shown in Figure Four, to display a figure in the background of the shot. Whilst Harry’s face is in clear focus in Figure Seven, an audience notice Bathilda twitching in an inhuman manner in the unfocused background. She begins to writhe and alter, and the transformation is an unearthly example of a human-animal relation as Nagini reverses the natural power dynamics between human and animal, which is a significantly chilling factor in typical depictions of animals in horror cinema. The type of shot is purposeful in creating a dramatic irony in Harry being unaware of the disturbance occurring behind him for several seconds, pushing the tension in the scene to a dramatic climax.

Figure Seven depicts light design within the scene as symbolism of the opposing forces of good and evil at play. For example, in the frame above, Harry and Bathilda’s faces are illuminated by a flame and a wand. The cool, crisp light of Harry’s wand and the warm light of the flame demonstrates how the practical lighting is used to illustrate a contrast – a contrast that indicates a difference between the characters, reiterating the narrative of good and evil. Here, Yates repeats his use of the shallow focus in a medium shot with a wider lens as shown in Figure Four, to display a figure in the background of the shot. Whilst Harry’s face is in clear focus in Figure Seven, an audience notice Bathilda twitching in an inhuman manner in the unfocused background. She begins to writhe and alter, and the transformation is an unearthly example of a human-animal relation as Nagini reverses power dynamics between human and animal and takes control, which is arguably a factor that chills an audience in depictions of animals on screen. The type of shot is purposeful in creating a dramatic irony in Harry being unaware of the disturbance occurring behind him for several seconds, pushing the tension in the scene to a dramatic climax.

In Figure Eight, Yates uses an extreme close up. I found this frame striking, particularly if considering Nagini’s character as a symbol of disorder to idealised femininity. The shot is in deep focus, depicting Bathilda’s facial features. The warm lighting emphasises the shadowed brown of her grotesque teeth, surrounded by a pair of pale, thin lips. The skin surrounding her mouth is deeply wrinkled, and upon looking at this shot, it forced me to imagine other extreme close up shots in film of female characters. Arguably, it seemed to be a reversal of the images often depicted.

Figure Eight – an intimate close up of the mouth.

Figure Nine – a frame of Mia Wallace’s lips from Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction.

As seen in Figure Nine, an extreme close up shot of the mouth is often used to emphasise beauty, sexuality and conventional femininity. In comparison to Figure Eight, Nagini’s female form is the complete opposite, with the shot of her lips emphasising an unpleasant alternative. This warped depiction of a typically feminine feature echoes Nagini’s ability as a character to disrupt traditional order. Her villainy and the common perception of serpents means she will consistently conjure a negative audience response. Thus here, when Nagini’s appearance is associated with gender nonconformity, her ‘baddy’ status is used to subtly reiterate the ‘bad’ within an unconventional female appearance.

Overall, the animal form of Hedwig and Nagini, their anthropomorphic personality traits, and their divided perception due to the discourse of species, all combine to provide the film with the suitable mode to make a gendered comment. By no means am I suggesting that the way to empower yourself as a female is to magically inhabit one’s grandparents and attack passers by. Instead, I want to point out how the unfair constructs surrounding types of animals are strikingly similar to the reductionist notions of femininity and gender evident in cinema, like this example. If we as viewers can understand the role that film has in “directing public perceptions of species”, then it becomes easier to notice how film has the power to influence public perceptions of factors like gender, race and sexuality.4

Further Reading:

James Walters, Fantasy Film: A Critical Introduction, (London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, 2011)

Katarina Gregersdotter, Johan A. Höglund, and Nicklas Hållén, Animal Horror Cinema: Genre, History and Criticism (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015)

Meredith Cherland, Harry’s Girls: Harry Potter and the Discourse of Gender, Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 52.4 (2009), 273-82 <https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.52.4.1>

The Psychologist, The Psychologist, 2016 <https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/heroes-and-villains>

References:

1. Breuer, Gabriel B, Jürg Schlegel, Peter Kauf, and Reto Rupf, ‘The Importance of Being Colorful and Able to Fly: Interpretation and Implications of Children’s Statements on Selected Insects and Other Invertebrates’, International Journal of Science Education, 37.16 (2015), 2664–87 (p. 2679).

2. Breuer, Gabriel B, Jürg Schlegel, Peter Kauf, and Reto Rupf, ‘The Importance of Being Colorful and Able to Fly: Interpretation and Implications of Children’s Statements on Selected Insects and Other Invertebrates’, International Journal of Science Education, 37.16 (2015), 2664–87 (p. 2664).

3. Breuer, Gabriel B, Jürg Schlegel, Peter Kauf, and Reto Rupf, ‘The Importance of Being Colorful and Able to Fly: Interpretation and Implications of Children’s Statements on Selected Insects and Other Invertebrates’, International Journal of Science Education, 37.16 (2015), 2664–87 (p. 2664, 2677).

4. Geest, Emily A, Ashley R Knoch, and Andrine A Shufran, ‘Villainous Snakes and Heroic Butterflies, the Moral Alignment of Animal-Themed Characters in American Superhero Comic Books’, Journal of Graphic Novels & Comics (2021), 1–16 (p. 2).

Bibliography:

Emily A. Geest, Ashley R Knoch, and Andrine A Shufran, ‘Villainous Snakes and Heroic Butterflies, the Moral Alignment of Animal-Themed Characters in American Superhero Comic Books’, Journal of Graphic Novels & Comics (2021), 1–16

Gabriel B. Breuer, Jürg Schlegel, Peter Kauf, and Reto Rupf, ‘The Importance of Being Colorful and Able to Fly: Interpretation and Implications of Children’s Statements on Selected Insects and Other Invertebrates’, International Journal of Science Education, 37.16 (2015), 2664–87

Figures:

2. Harry Potter Wiki, https://harrypotter.fandom.com/wiki/Maledictus

3. Harry Potter Wiki, https://harrypotter.fandom.com/wiki/Hedwig

4. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part I, 2010, Warner Bros. Pictures.

5. Tenor, https://tenor.com/view/nagini-harry-potter-fantastic-beasts-jkr-gif-12580197

6. Wizarding World, https://www.wizardingworld.com/features/all-the-times-hedwig-proved-she-was-the-queen-of-sass

7. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part I, 2010, Warner Bros. Pictures.

8. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part I, 2010, Warner Bros. Pictures.

9. Film School Rejects, https://filmschoolrejects.com/quentin-tarantino-perfect-shots/