Figure 1: The original cinematic release poster for Gates of Heaven.

Eighty-Five minutes of predominantly medium close-up shots without narration with a focus, superficially at least, on the pet cemetery business. You may think that the initial prognosis for Errol Morris’s 1978 debut Gates of Heaven is bleak; indeed you would be in good company.[1] Morris’s fleeting between concepts led Werner Herzog to promise to eat his shoes if it was ever publically exhibited. The next year Herzog chowed down on the mortal remains of a cow that met an end less fortunate than a plush plot in the California sunshine (fig. 2).[2] Live animals are, unsurprisingly, almost completely absent from the film. The main drama concerns the exhumation of hundreds of pets from a bankrupted cemetery and their reburial with a competitor. The absence, as opposed to presence, of animals casts an incredible light on the lives of those featured. Morris’s purposefully vague interviews with pet-owners and staff are augmented with poignant and unusual shots of scenery in order to reinforce the film’s cryptic tagline (fig. 1).

Figure 2: A still of Werner Herzog’s aforementioned eponymous shoe from the short documentary Werner Herzog Eats his Shoe.

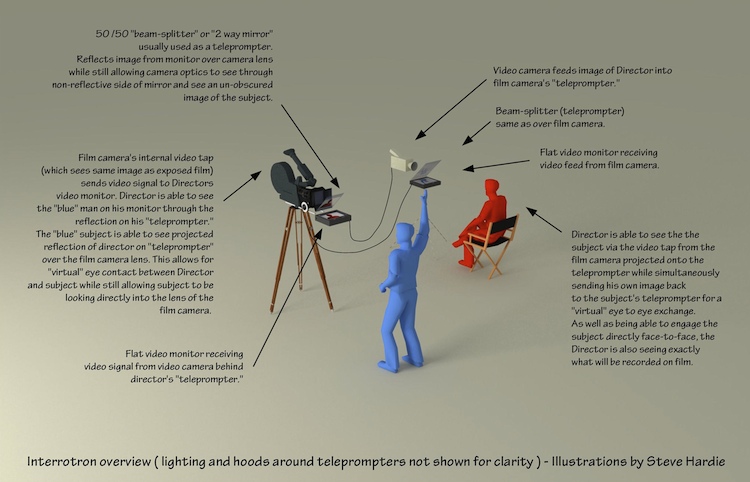

Louis Theroux’s famous forays into Nazism and pornography (as an observer of course) owe a lot to Morris’s debut.[3] Yet the differences between Theroux’s style and that of his generic predecessor are stark. Theroux’s tricky (‘Hi I’m Louis!’) vocally involved style contrasts completely with the front-on intensive interviewing technique (fig. 3) that has become synonymous with Morris’s work. Morris’s elective mutism compliments the aesthetic simplicity of the film. Long monologues abound and, as Brandon Irvine states, it would be easy to ‘walk out of the theatre thinking you’d simply seen an investigative report on an exceedingly dry topic’.[4] Yet the discussion of animals serves as the metaphorical gateway into the lives and feelings of the subjects. Film theory grandee Bill Nichols asserts that ‘In documentaries we find stories or arguments, evocations or descriptions that let us see the world anew’[5]. Through careful juxtaposition of the absurd subject matter with scenery-implied significance and the passion and emotional involvement of quirky subjects Morris does just this, creating a tragi-comic offbeat masterpiece.

Figure 3: A diagram of the Interrotron filming setup that allows for Morris’s characteristic interview technique.

Ironically as Morris sat and dismembered his raw footage a rendering plant dismembered animals next door. This juxtaposition is reflected in the sequence editing itself which, along with Morris’s choice of backdrops, create silent distinctions between the three featured businesses. The paraplegic Floyd McClure, proprietor of the failed Foothill Pet Cemetery in Los Altos, is the first subject of the film. McClure’s life is presented pastorally; he sits on his farm (complete with elusive live dog) in an unbuttoned shirt and braces (fig. 4). McClure’s interviews alternate with those of the plant manager who is filmed with a seriousness that reflects his macabre trade; he is in his office, with the window framing a nondescript but ominous industrial backdrop. Morris’s self-defined ‘ecstatic absurdity’ is never too far away either; in the second half of the film McClure’s Napa rivals talking dead dogs with their bond-villain globes, garish shirts and ultramarine swimming pools (fig. 5).[6] Morris’s visual distinctions and juxtaposition of interviews emphasise differences between the attitudes of the three men. McClure’s work is his vocation, a quasi-religious offering to ‘Mother Nature’. The rendering plant manager is either unempathetic or sociopathic and the second cemetery is full of business-like name boards, trophies and entrepreneurial masterplans.

Figure 4: A film still showing Floyd McClure sitting in his garden. The straight-on medium close-up shot in use is typical of the results offered by the Morris’s Interrotron filming setup.

The subjects aren’t the only things that are juxtaposed. The business spiel is broken up by small reminders of the film’s silent subjects: the animals. Frozen pets often oversee proceedings, sometimes in frames on the wall and sometimes as frames of the film itself. Monotone newsprint clarifies colourful accounts through blunt headlines. Secondary shots relating to the realities of the backstory are sparse but significant. The longest of these is a montage of headstones; each featured for slightly too long so the viewer must read the inscriptions and consider the photographs (fig. 7). Tippins, Jou-Jou and Andy become ‘Our Angel’, ‘Our Love’ and ‘Our Son’ respectively. Morris’s not-so-random cross-section illustrates the potential intensity of owner-pet relationships and highlights the personification of animals by their owners. Indeed at points personification gives way to fully-fledged role-reversal as the viewer is informed that grandparents ‘need grandchildren to rear’. Gates of Heaven features a sliding scale of posthumous potentials from undignified glue production to elaborate beatification. Despite the difference in aesthetic outcome all of the businesses involved are dependent on the same commodity: dead animals. Indeed, elephants and giraffes aside, the cemetery trade is definitely the more lucrative. Throughout the film Morris’s questions provoke slips from the emotional rhetoric of ‘deserving animals’ to talk of ‘advanced selling plans’.

Figure 5: An unusually casual scene for the subject matter, saturated by the colours of the pool, the kitsch telephone and the fine example of 1970s casualwear.

These commercial realities seem harsh given the delicate subject matter. We should only have to see the unmarked truck snaking away from McClure’s cemetery or listen to one of the pet owners to remember the grim backstory. The scenes with the trucks are indeed dark but the owner interviews that Morris uses sporadically are often surprisingly ambiguous. About halfway through the film we are treated to the film’s longest scene; an old woman, Florence Rasmussen, sits on a rocking chair in her doorway and spontaneously metamorphoses from the understated caterpillar of relevance to a beautiful rambling butterfly (fig. 6). He is willing to superficially lose himself in Rasmussen’s monologue but he must have soon realised its potential as the thread that sews together his patchwork project. It sits almost directly halfway through the film, after McClure and before Napa, and could be taken as Morris’s support for his suggestion that: ‘if you scratch the surface of any person, you will find a world of the insane, very close to that surface’.[7] Rasmussen briefly recaps the background story before giving up with an ‘Ah well’. She plods through a discussion of her disability, passes a scathing and stereotypical judgement with regards to her daughter-in-law and criticises her absent son. The fate of the cemetery allows Rasmussen an opportunity to vocalise her plethora of problems and questions that she can’t refuse.

Figure 6: Florence Rasmussen delivering her monologue in the scene that many critics agree divides the two halves of the film.

Despite the discussion of the moral ins and outs of different forms of animal disposal Gates of Heaven offers no insight into the lives of animals themselves; it is only concerned with the effects of the absence of these animals on owners and associated businesses. The film’s tagline ‘Death is for the living and not for the dead so much’ emphasises the fact that the human subjects are all dependent, one way or another, on animals. The live animals have had disproportionately large roles in the lives of their generally quirky, isolated owners and once dead they become a commodity that the business machinery of the Napa cemetery or rendering plant is eager to consume. The meeting of loving, if eccentric, pet owners and savvy, if badly dressed, Napa businessmen inspires the elaborate and emotional memorials exhibited by Morris. The animals in Gates of heaven are silent; they exist solely for the enjoyment or enrichment of their human owners (fig. 7).

Figure 7: A film-still showing an example from the long procession of memorial headstones featured by Morris towards the end of the film.

Throughout the film these non-existent animals provide a staggering gateway into the world of the subjects. The talk of animals is the pan-European (or pan-Californian) currency that lowers the guard of everyone except the Eurosceptic rendering plant manager. Pet ownership is a coping mechanism for the abandoned Rasmussen and the disabled McClure. Rasmussen’s monologue proves that once prompted with the mention of their animals the subjects are completely willing to discuss a wide array of personal problems. In Morris’s owner interviews the loss of an animal becomes a metaphor for loss as a whole and the need for memorialisation becomes representative of the need for consolation and attention amongst humans that are somehow deprived. Despite their silence the animals have clearly been used in lieu of humans and are presented as unquestioning and universal confidantes and companions to their unusual owners.

Figure 8: The colourful closing scene of Gates of Heaven features an altar in the Napa cemetery set against the backdrop of a spectacular Californian sunset.

Werner Herzog loved Morris so much he gave his shoes in a show of cinematic approval. His role in inspiring Morris to niche, cult-classic documentary greatness cannot be understated. Herzog’s 2005 film Grizzly Man has shares some of the offbeat features of Morris’s debut but is diverted by Herzog’s invasive involvement and dark commentary.[8] Both films revolve around eccentric animal lovers. In Herzog’s film Timothy Treadwell acts as the preeminent flag bearer for army of quirkiness. Treadwell is as, if not more, dependent upon animals as his pet-cemetery counterparts. Treadwell’s bears have the same supportive and rehabilitative role as Tippins and Jou-Jou but are altogether more socially problematic because of they are a) alive and b) capable of eating humans. Ultimately Grizzly Man differs because it has an obvious agenda that is defined by an openly subjective and vocal director whereas Morris has often proclaimed his own objectiveness and the absurdity of his story encourages the viewer to make their own judgements. This is easy because the stakes are not life or death as in Grizzly Man; in Gates of Heaven literal death is for the animals and not for the humans so much.

[1] Gates of Heaven, dir. Errol Morris. New Yorker Films, 1978.

[2] Werner Herzog Eats his Shoe, dir. Les Blank. 1980.

[3] Louis Theroux’s Weird Weekends, dir. Louis Theroux. BBC Bristol, 1998-2000.

[4] Bradon Irvine, Brattle Theatre Film Notes, ‘Gates of Heaven’ (30th November 2011) < https://www.brattleblog.brattlefilm.org/2011/11/30/gates-of-heaven-1216/> [accessed 29th January 2011].

[5] Bill Nichols, Introduction to Documentary, 2nd edn. (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2001), p. 3.

[6] The Believer, ‘Werner Herzog [Filmmaker] in Conversation With Errol Morris [Documentarian]’ (March 2008) <https://www.believermag.com/issues/200803/?read=interview_herzog> [accessed 31st January 2015].

[7] Noel Murray, A.V. Club, ‘Errol Morris’ (September 14th 2005) < https://www.avclub.com/article/errol-morris-13951> [accessed 14th January].

[8] Grizzly Man dir. Werner Herzog. Lion’s Gate Entertainment, 2010.

Bibliography:

Books:

Nichols, B., Introduction to Documentary, 2nd edn (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2001)

Films:

Blank, L. (dir.), Werner Herzog Eats his Shoe, 1980.

Herzog, W. (dir.), Grizzly Man. Lions Gate Entertainment, 2005.

Morris, E. (dir.), Gates of Heaven. New Yorker Films, 1978.

Theroux, L. (dir.), Louis Theroux’s Weird Weekends. BBC Bristol, 1998-2000.

Webpages with authors:

Irvine, B., Brattle Theatre Film Notes, ‘Gates of Heaven’ (30th November 2011) < https://www.bra ttleblog.brattlefilm.org/2011/11/30/gates-of-heaven-1216/> [accessed 29th January 2011].

Murray, N., A.V. Club, ‘Errol Morris’ (September 14th 2005) < https://www.avclub.com/article/errol-morris-13951> [accessed 14th January].

Webpages without authors:

The Believer, ‘Werner Herzog [Filmmaker] In Conversation With Errol Morris [Documentarian]’ (March 2008) <https://www.believermag.com/issues/200803/?rea d=interview_herzog> [accessed 31st January 2015].

Further Reading:

Roger Ebert’s review of Gates of Heaven that did so much to propel the film to notoriety:

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-gates-of-heaven-1978

An online analysis of the Interrotron filming setup that allows for Morris’s characteristic filming technique:

The Rotten Tomatoes page for the film, featuring a wide array of reviews:

https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/gates_of_heaven_1980/

A particularly interesting interview between Morris and Werner Herzog that features some discussion of the differences and similarities of between their approaches to filmmaking. Herzog also offers his interpretation of Gates of Heaven:

Believer Mag: https://believermag.com/issues/200803/?read=interview_herzog

The IMDB page for the film, with details of the cast, scenery, release etc.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0077598/

Errol Morris’s own entry on Gates of Heaven on his own personal webpage:

https://www.errolmorris.com/film/gates.html

An interview with Morris that discusses the prospects of Gates of Heaven when it was initially released and the inspirations behind the film:

https://www.avclub.com/article/errol-morris-13951

A filmed interview for the Film Society of Lincoln Center where Morris discusses the release of Gates of Heaven and offers some explanation of the film’s meaning:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJzV07VkD_I

Last but not least some excerpts from the masterpiece Werner Herzog Eats his Shoe:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJzV07VkD_I