Lee Unkrich’s Coco (2017) is built on similar foundations of recent Disney/Pixar releases alike Moana(2016) and The Good Dinosaur(2015); twelve year old Miguel’s (Anthony Gonzalez) dream of becoming a musician compromises his family’s ban on music and their hope for Miguel to continue the family business.[i]Yet what may feel like recognisable narrative territory, the enriched setting of traditional Mexico during the night of Día de los Muertos are uncharted grounds for the studio and potentially for the audience to experience on screen. When Miguel becomes trapped in the Land of the Dead, extra responsibility is placed upon the position of his animal companion to help navigate these unknown worlds. His Abuelita’s warning of naming a street dog as they ‘will follow you for life’ is rendered false, as instead it is Miguel who follows Dante through life and passing into death. By characterising Dante as a ‘good dog’, the popularity of this species to feature in Western cinema means his body acts as a point of familiarity to transform this world into something recognisable to Disney/Pixar’s global audience. Dante’s responsibility as a ‘spirit guide’ comes to encompass more than the reunion between Miguel and his long lost, and deceased, grandfather, for his body acts as signposts for the audience to follow across this potentially alienating world.

Unkrich explains that Dante has been part of the journey in creating Cocosince the beginning; ‘When we were coming up with the ideas for Coco, pretty early on we came up with the idea of Miguel having a dog’.[ii]Before he can even be characterised or developed, before he is even Dante, there is this requirement for there to be a dog. Such desire to possess and feature a dog indicates the species holds a significance that no other can replicate and a value that is integral to the film. Whilst the target audience being the whole family means there is already an inclination for Dante to be a positive role model, this is not the first time we have encountered a ‘good boy’ such as Dante. In fact, this specific representation of the dog can be tracked and followed throughout Western film history. The ‘cult of the dog hero’, along with the expectations and association of this stock character, have remained fairly consistent since its origins. Cultivated in the 1920s by the German shepherd Rin Tin Tin, it is as though to qualify as a ‘good boy’ an onscreen dog must be loyal, dependable, intelligent, lifesaving, or willing to travel vast distances to reunite with its owners.[iii]Yet what has changed dramatically is the popularity of this image, with films featuring a dog as a protagonist were release at a rate of less than one per year until 1940, when this rate grew to more than seven a year in 2005.[iv]Whilst Pixar have yet to focus upon a dog as the central character, they have had responsibility in the continuation and encouragement of this identity, fortracing across their filmography reveals the lurking and presence of this ‘good boy’ to feature. Even when immersed within the world of living toys, Slinky-dog is still described ‘as loyal as any other dog’, or on adventures in floating houses, the extent of Dug’s devotion to remain close to his master Carl means risking his life ‘hiding under your porch because I love you’.[v]For the audience to recognise the similarities between these dogs demonstrates the strength and rigidity of the idea of ‘the good boy’ to remain unchanged. Dante may transgress between the Land of the Living and the Dead, but in his characterisation as a dog, he has already spanned across the Pixar and cinematic universe, for almost a century.

Dante follows the examples set by his canine peers as he conforms to the ideals of the trope that determine his deserving of being the ‘good boy’. He demonstrates his loyalty in his refusal to leave Miguel’s side. Even when he is unfairly scolded and abandoned by Miguel, he still returns to rescue him when he is trapped in a cave. Dante is repeatedly there to save Miguel, whether that is to help him fight off security guards or catch him from falling buildings. Yet he is more than just heroic, but his devotion for his owner is obvious and present from the very beginning when he is the only one who will accept Miguel as the musician he desires to be. We become so convinced in his portrayal of the dog, that even when he is an accepted and recognised as a spirit guide, he still remains associated with the image of the ‘good boy’. When Miguel asks ‘Who’s a good spirit guide? You are!’, the substitution of the ‘dog’ for ‘spirit guide’ demonstrates that he retains this close attachment to his previous form, as though it is impossible for him to stray too far from the image of the dog. It becomes even more convincing when reading across headlines of reviews that found the featuring of a ‘lovable’ and ‘very good dog’ the most resonating element of the film.[vi]Together these qualities convince us of Dante’s ability as the animal companion and since he successfully completes this duty, he is rewarded in the transform into the heightened and powerful state that is a ‘Spirit Guide’.

Crucially the crux of his attainment of becoming this ‘Spirit Guide’ and the title of ‘good boy’ relies upon his success in reuniting Miguel and his grandfather. Although at times his attempts are misconstrued as an annoyance and unhelpful to Miguel, retrospective watching reveals these moments as Dante’s effort to encourage Miguel towards Hector (Gael García Bernal). When they are together, Dante appears calm and content as though his job is complete, but when separated Dante becomes anxious and displays chaotic behaviours. This awareness of their relation indicates Dante retains both an emotional intelligence and omniscient knowledge that no other – human, skeleton or audience – possesses. However, this also means that for Dante to succeed as a dog, he must subvert the ‘one trope in dog-centric films’ that ‘has been explored to the point of exhaustion’, the ‘Coming Home’ narrative.[vii]Unlike the other ‘dog-centric’ films that Chodoshacknowledges, such as Lassie (1943) or The Incredible Journey (1963), Dante is never separated from his owner or family, meaning his role is not to be return himself but rather to reunite Miguel and restore his fragmented family back together. By employing and engaging with these clichés and conventions, Dante becomes closer aligned with the Western cinematic construction of the dog, convincing the audience of capabilities as the animal companion in his ability to help navigate Miguel, and consequently the audience, back home safely.

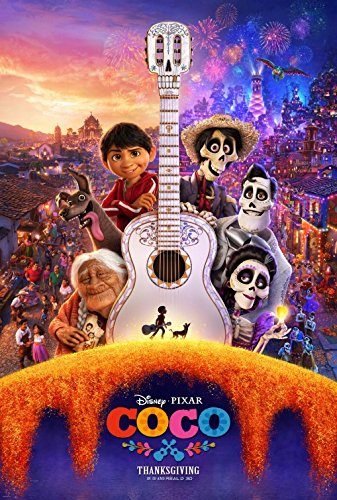

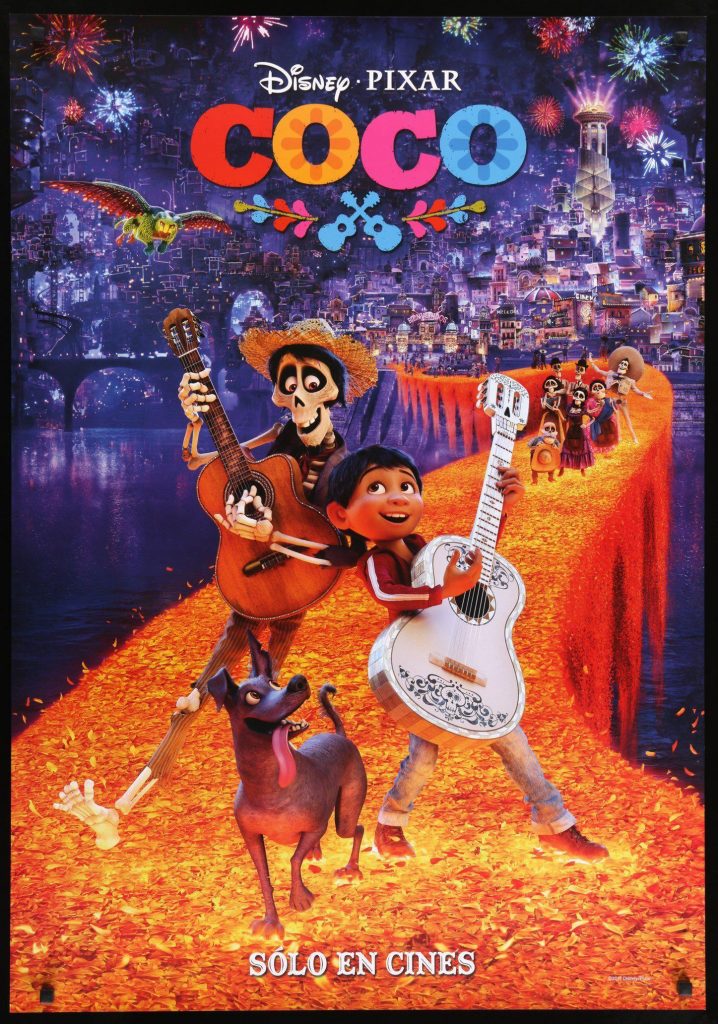

Dante is given the responsibility to guide and encourage the audience before the film can even begin. Three months before the release of the official trailer Pixar premiers Dante’s Lunch with the intension for it to ‘introduce’ and ‘appetize’ yet focuses entirely, as the title suggests, on Dante.[viii]And these are not his only two minutes of fame, but across the film’s advertising posters they consistently place Dante in the centre and where his body is either easily distinguishable as a dog, or the only figure at all. Each of these posters subtly hint at his duty of ‘spirit guide’, as he is often depicted in the foreground or in front of Miguel in the hopes that audiences may emulate him and follow Dante; whether that be into the cinema, to buy the DVD or click play on Netflix. Such heavy featuring of Dante across all the marketing material highlights the vitality for audiences to acknowledge Dante and his participation within the film. It is as though they fear audiences who are unfamiliar with Latin cultures and themes, will feel alienated and unrepresented so may avoid the film. In promising the mere presence of a dog, and our comfortability and compliance to welcome this image,Dante’s body becomes a symbol of familiarity as an attempt to reassure the universal appeal of the film.

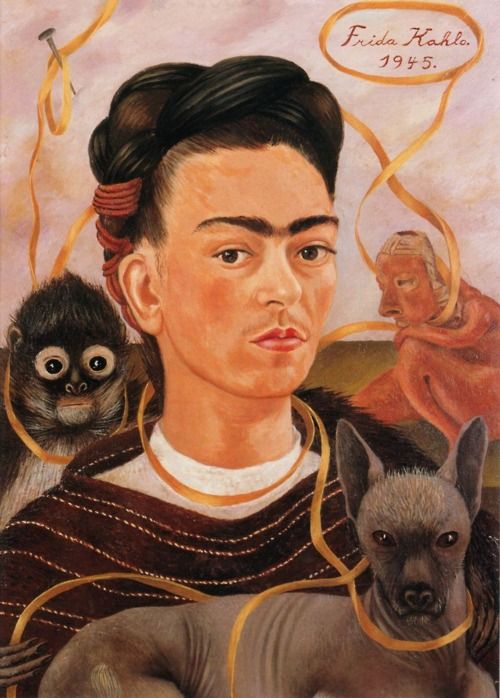

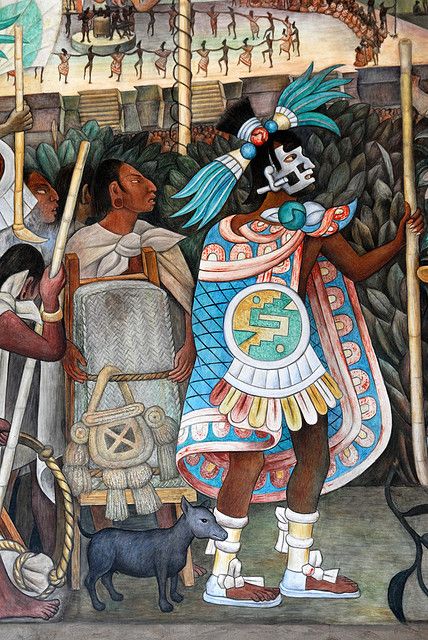

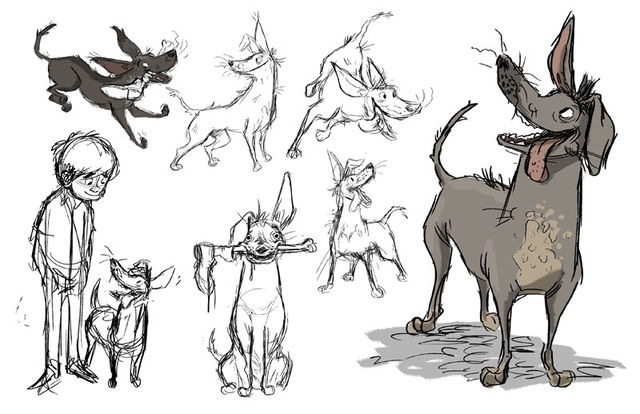

Thus Dante comes to be integral for the film’s social, ideological and economic success as his body acts as a bridge into the new, unfamiliar cultures and territories. Pixar combines the conventions of the common dog as way to gain access into this new world, to be an entry point for those who may feel disconnected from the Mexican setting. However, whilst Dante’s personality corresponds to the ideas and conventions that are so prevalent and commonplace, they are packaged into a body that is less familiar. Dante’s breed as a Xoloitzcuintli (Xolo for short) may be unusual on the tongue, but his hairless, wart covered skin, missing teeth and broken tail are more out of place within animation.[ix]Yet as the national dog of Mexico, heavy featuring within the art of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera along with 3500 years of history in Mesoamerican culture, the Xolo dog will be less of a stranger to indigenous audiences.[x]According to Aztec mythology, the Xoloitzcuintli was instructed by Xolotl, the God of lightning and death and whom the breed is named after, to guide Man through the dangers of Mictlan, the world of Death, towards the Evening Star in the Heavens.[xi]Dante’s role within the film just closer associates it with his origins and the mythologies of his breed. For those aware of these folklores, the big reveal of Dante’s responsibility to ‘guide’ the ‘wandering spirit’ of Miguel may not come as a big surprise or twist, but by transforming Dante’s body into this Spirit Guide, it roots him deeper and authentically within Mexican culture.

For those who are less familiar with the breed nor of their deep and enriched history, Dante becomes a tool to educate outside audiences as these complex and detailed ideas are packaged within this recognisable form. When he transforms into a Spirit Guide towards the end of the film, we can quickly comprehend their qualities and characteristics since they have been aligned with our cultural ideas and expectations of the dog. The history that may have felt separate and unattainable for Western audiences, becomes easily understood and navigated because it is made familiar in presenting it via the body of the dog. Dante allows for further appreciation of Mexican culture that goes beyond surface level aesthetics, since Xolo dogs have such an enriched history that expands further than the cinema screen. Dante becomes an access point, something of interest or significance that may be the start for those who may wish to explore further. The territory that Dante helps us navigate broadens further than the one shown on screen, as it is not just the fictional Land of the Dead but this in fact reflects a larger, denser Mexico.

Pixar updates the body of the Xolo from the Aztec clay sculptures or that of Frida Kahlo’s paintings onto a new canvas of CGI animation, in a refreshing, updated interpretation accessible for all audiences. They apply pressure on the cultural ideas and the history of the Xolo dog, with the conventions of the dog in Western cinema, to construct Dante. In turn he becomes something new, a walking melting pot as his body is created as a collage of an amass of cultures and ideas of the conception of the dog.He is a dog, but one which resonates and conforms to the ideals of both the Latin and the Western viewer. These different features and ideas as appropriated from across the globe, amalgamate in order to create a dog that is recognisable and identifiable for all. He remains true and authentic to his ancient heritage in order to stay respectful and camouflaged within the films setting. But crucially, the film projects the conventional tropes in the Western construction of the ‘good boy’ upon the body of Dante and relies upon our ability to recognise and identify with these, in order for an easier negotiation of this strange and unfamiliar world.

[i]Moana, dir. by. Ron Clements, John Musker (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2016).

The Good Dinosaur, dir. by. Peter Sohn (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2015).

[ii]On the Set Coco [Dante (Xoloitzcuintli or Xolo), online video recording, YouTube, Feb 14,2018 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kOV7uzrsp7o&t=153s> [accessed 14/01/2019].

[iii]Caleb Chodosh, ‘Good Boy: Canine Representation in Cinema’, Momentum, 5.1 (2018) pp.8-17 < https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1043&context=momentum> [accessed 14/01/2019] (p.10)

[iv]Stefano Ghirlanda, ‘Dog Movie Stars and Dog Breed Popularity: A Case Study in Media Influence on Choice’,Public Library of Science, 9.9 (2014) pp.1-5 < https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0106565&type=printable> [accessed 14/01/2019] (p.2).

[v]Toy Story, dir. by. John Lasseter (Buena Vista Pictures Distribution, 1995).

Up, dir. by. Pete Docter (Walt Disney Pictures Motion Studios, 2009).

[vi]Joanna Robinson, ‘Pixar Introduces Coco’s Lovable Dog With All-New Short’, Vanity Fair, 29 March 2017 < https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/03/coco-pixar-short-dante-dog-xolo> [accessed 14/01/2019] Hillary Busis, ‘Coco Review: Pixar’s Latest Has Wit, Style, and a Very Good Dog’, Vanity Fair, 21 November 2017, <https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/11/coco-movie-review-pixar-day-of-the-dead> [accessed 14/01/2019].

[vii]Chodosh, ‘Good Boy: Canine Representation in Cinema’, (p.12).

[viii]Disney UK,COCO | Dante’s Lunch… A Short Tail | Official Disney Pixar UK | Official Disney UK, YouTube, 29 March 2017 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6rOKoa6RSHM> [accessed 14/01/2019] .

Gwynne Watkins, ‘New Pixar Short “Dante’s Lunch” Introduces ‘Coco’ Dog, Plus Director Lee Unkrich on Whether ‘Coco’ Will Make You Cry (Exclusive)’, Yahoo, 29 March 2017 <https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/new-pixar-short-dantes-lunch-introduces-coco-dog-plus-director-lee-unkrich-on-whether-coco-will-make-you-cry-exclusive-155901674.html> [accessed 14/01/2019] .

[ix]Jenna Busch, ‘Pepita and Dante: Meet the Creatures of Disney•Pixar’s Coco’, Coming Soon.Net, 2 November 2017 < https://www.comingsoon.net/movies/features/899979-pepita-and-dante-meet-the-creatures-of-coco#WWzfWYROXFO46ESe.99> [accessed 14/01/2019]

[x]Kristin Romey, ‘This Hairless Mexican Dog Has a Storied, Ancient Past’, National Geographic, 22 December 2017 <https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/11/hairless-dog-mexico-xolo-xoloitzcuintli-Aztec/> [accessed 14/01/2019]

[xi]Sandra L. Bridges, ‘Origins & History of the Xoloitzcuintli’, Xoloitzcuintli Club of America, 2013 < http://www.xoloitzcuintliclubofamerica.org/breed_history> [accessed 14/01/2019].

Suggestions for further reading;

Michael Lawrence,‘Practically infinite manipulability’: domestic dogs, canine performance and digital cinema’, Screen, Vol.56. (2015) pp.115-120.

Adrienne L. McLeanCinematic canines : dogs and their work in the fiction film(Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey. 2014)

Grace Wearden, ‘Mirrors & Windows: Why Diversity Must Be Better Represented in Children’s Fiction’, Jameson First-Year Writing Contest Winners, 3.1 (Spring 2018).

Bibliography

Bridges, Sandra L., ‘Origins & History of the Xoloitzcuintli’, Xoloitzcuintli Club of America, 2013 < http://www.xoloitzcuintliclubofamerica.org/breed_history> [accessed 14/01/2019].

Busch, Jenn., ‘Pepita and Dante: Meet the Creatures of Disney•Pixar’s Coco’, Coming Soon.Net, 2 November 2017 < https://www.comingsoon.net/movies/features/899979-pepita-and-dante-meet-the-creatures-of-coco#WWzfWYROXFO46ESe.99> [accessed 14/01/2019]

Busis, Hillary. ‘Coco Review: Pixar’s Latest Has Wit, Style, and a Very Good Dog’, Vanity Fair, 21 November 2017, <https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/11/coco-movie-review-pixar-day-of-the-dead> [accessed 14/01/2019].

Chodosh, Caleb. ‘Good Boy: Canine Representation in Cinema’, Momentum, 5.1 (2018) pp.8-17 < https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1043&context=momentum> [accessed 14/01/2019]

Clements,Ron.John Musker, dir,. Moana, (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2016).

Disney UK,COCO | Dante’s Lunch… A Short Tail | Official Disney Pixar UK | Official Disney UK, YouTube, 29 March 2017 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6rOKoa6RSHM> [accessed 14/01/2019] .

Docter, Pete, dir,. Up(Walt Disney Pictures Motion Studios, 2009).

Ghirlanda, Stefano. ‘Dog Movie Stars and Dog Breed Popularity: A Case Study in Media Influence on Choice’, Public Library of Science, 9.9 (2014) pp.1-5 < https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0106565&type=printable> [accessed 14/01/2019]

Lasseter, John, dir,.Toy Story,(Buena Vista Pictures Distribution, 1995).

Lawrence, Michael.‘Practically infinite manipulability’: domestic dogs, canine performance and digital cinema’, Screen, Vol.56. (2015) pp.115-120 <https://watermark-silverchair-com.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/hjv009.pdf?token=AQECAHi208BE49Ooan9kkhW_Ercy7Dm3ZL_9Cf3qfKAc485ysgAAAlswggJXBgkqhkiG9w0BBwagggJIMIICRAIBADCCAj0GCSqGSIb3DQEHATAeBglghkgBZQMEAS4wEQQMftCOKc7q12jbKLLbAgEQgIICDgcmzpiS5wJvETkfdgRbG_8ufMBaTWnJ18TTmyqAN1YY-EdhJqLBXDc4jhIXjZze5QwkhBJyn335VAqtc-PAu3j6aDgHerUJ6hRcVuZO5Fkvy4ztOLJUbrA_tptd-Jg8Nm0swbtwsfLDECNJxEQi-d2TepNcnnzFs01lonad20wHevwNEwt4dI4PcFhzXpr-QnKcT4FgZ4qA2nInrPh48yTkwQKtXRjTyR50LaqNRXPxvD_clBXKXds4zElyJFm1ekq8Aq2KE2IColkcDQeQyRtBegfRhqfW7Mc1MYk2ySssXwddj4PiA1Mz8XsC0P8UhpFvrK6Er1mOE0XY2xZWY0MW78V50tzGwobuPMxCnSC-yX0CkWxhpTD9wG2y5_oQ1tIctCQOs6cVqxPFSC_WKAzEHn4VQwaX8MuRvHOo1zWepH6E47aaP-0ToxVpNe5gk__tVRU7Sy2x9yDP8SBQcKvb8Sl6QwuqHIcYWaG9tEU8aL-iNF1xBsqIE4Ye6-H-eukI7EGW7RCjMSR8RZn_6394Dpj9CBLdzyrxb7RwHZ7FyC1kcaTbcoFCSOC9QJUZWDTkfol65i-0HZ-K0WnfGK8qYBI3-CN5YvhvfwCLeuXTfsPX7dCE9TuhHhlZabAxtmf7d8ADaLntIO3rJLrG6nJ65IeimX-M2ir-UJDIy2jv9-dSV3NsKeRGvLHhc68> [accessed 14/01/2019]

McLean, Adrienne L.. Cinematic canines : dogs and their work in the fiction film,

(Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey. 2014)

On the Set Coco [Dante (Xoloitzcuintli or Xolo), online video recording, YouTube, Feb 14, 2018 < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kOV7uzrsp7o&t=153s> [accessed 14/01/2019].

Robinson, Joanna. ‘Pixar Introduces Coco’s Lovable Dog With All-New Short’, Vanity Fair, 29 March 2017 < https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/03/coco-pixar-short-dante-dog-xolo> [accessed 14/01/2019]

Romey Kristin. ‘This Hairless Mexican Dog Has a Storied, Ancient Past’, National Geographic, 22 December 2017 <https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/11/hairless-dog-mexico-xolo-xoloitzcuintli-Aztec/> [accessed 14/01/2019]

Sohn, Peter, dir,.The Good Dinosaur, (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2015).

Unkrich, Lee, dir,. Coco, (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2017).

Watkins, Gwynne. ‘New Pixar Short “Dante’s Lunch” Introduces ‘Coco’ Dog, Plus Director Lee Unkrich on Whether ‘Coco’ Will Make You Cry (Exclusive)’, Yahoo, 29 March 2017 <https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/new-pixar-short-dantes-lunch-introduces-coco-dog-plus-director-lee-unkrich-on-whether-coco-will-make-you-cry-exclusive-155901674.html> [accessed 14/01/2019] .

Wearden, Grace. ‘Mirrors & Windows: Why Diversity Must Be Better Represented in Children’s Fiction’, Jameson First-Year Writing Contest Winners, 3.1 (Spring 2018). <https://journals.wheaton.edu/index.php/wheaton_writing/article/view/527> [accessed 14/01/2019]

[1]Moana, dir. by. Ron Clements, John Musker (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2016).

The Good Dinosaur, dir. by. Peter Sohn (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2015).

[1]On the Set Coco [Dante (Xoloitzcuintli or Xolo), online video recording, YouTube, Feb 14,2018 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kOV7uzrsp7o&t=153s> [accessed 14/01/2019].

[1]Caleb Chodosh, ‘Good Boy: Canine Representation in Cinema’, Momentum, 5.1 (2018) pp.8-17 < https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1043&context=momentum> [accessed 14/01/2019] (p.10)

[1]Stefano Ghirlanda, ‘Dog Movie Stars and Dog Breed Popularity: A Case Study in Media Influence on Choice’,Public Library of Science, 9.9 (2014) pp.1-5 < https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0106565&type=printable> [accessed 14/01/2019] (p.2).

[1]Toy Story, dir. by. John Lasseter (Buena Vista Pictures Distribution, 1995).

Up, dir. by. Pete Docter (Walt Disney Pictures Motion Studios, 2009).

[1]Joanna Robinson, ‘Pixar Introduces Coco’s Lovable Dog With All-New Short’, Vanity Fair, 29 March 2017 < https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/03/coco-pixar-short-dante-dog-xolo> [accessed 14/01/2019] Hillary Busis, ‘Coco Review: Pixar’s Latest Has Wit, Style, and a Very Good Dog’, Vanity Fair, 21 November 2017, <https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/11/coco-movie-review-pixar-day-of-the-dead> [accessed 14/01/2019].

[1]Chodosh, ‘Good Boy: Canine Representation in Cinema’, (p.12).

[1]Disney UK,COCO | Dante’s Lunch… A Short Tail | Official Disney Pixar UK | Official Disney UK, YouTube, 29 March 2017 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6rOKoa6RSHM> [accessed 14/01/2019] .

Gwynne Watkins, ‘New Pixar Short “Dante’s Lunch” Introduces ‘Coco’ Dog, Plus Director Lee Unkrich on Whether ‘Coco’ Will Make You Cry (Exclusive)’, Yahoo, 29 March 2017 <https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/new-pixar-short-dantes-lunch-introduces-coco-dog-plus-director-lee-unkrich-on-whether-coco-will-make-you-cry-exclusive-155901674.html> [accessed 14/01/2019] .

[1]Jenna Busch, ‘Pepita and Dante: Meet the Creatures of Disney•Pixar’s Coco’, Coming Soon.Net, 2 November 2017 < https://www.comingsoon.net/movies/features/899979-pepita-and-dante-meet-the-creatures-of-coco#WWzfWYROXFO46ESe.99> [accessed 14/01/2019]

[1]Kristin Romey, ‘This Hairless Mexican Dog Has a Storied, Ancient Past’, National Geographic, 22 December 2017 <https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/11/hairless-dog-mexico-xolo-xoloitzcuintli-Aztec/> [accessed 14/01/2019]

[1]Sandra L. Bridges, ‘Origins & History of the Xoloitzcuintli’, Xoloitzcuintli Club of America, 2013 < http://www.xoloitzcuintliclubofamerica.org/breed_history> [accessed 14/01/2019].

Suggestions for further reading;

Michael Lawrence,‘Practically infinite manipulability’: domestic dogs, canine performance and digital cinema’, Screen, Vol.56. (2015) pp.115-120.

Adrienne L. McLeanCinematic canines : dogs and their work in the fiction film(Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey. 2014)

Grace Wearden, ‘Mirrors & Windows: Why Diversity Must Be Better Represented in Children’s Fiction’, Jameson First-Year Writing Contest Winners, 3.1 (Spring 2018).

Bibliography

Bridges, Sandra L., ‘Origins & History of the Xoloitzcuintli’, Xoloitzcuintli Club of America, 2013 < http://www.xoloitzcuintliclubofamerica.org/breed_history> [accessed 14/01/2019].

Busch, Jenn., ‘Pepita and Dante: Meet the Creatures of Disney•Pixar’s Coco’, Coming Soon.Net, 2 November 2017 < https://www.comingsoon.net/movies/features/899979-pepita-and-dante-meet-the-creatures-of-coco#WWzfWYROXFO46ESe.99> [accessed 14/01/2019]

Busis, Hillary. ‘Coco Review: Pixar’s Latest Has Wit, Style, and a Very Good Dog’, Vanity Fair, 21 November 2017, <https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/11/coco-movie-review-pixar-day-of-the-dead> [accessed 14/01/2019].

Chodosh, Caleb. ‘Good Boy: Canine Representation in Cinema’, Momentum, 5.1 (2018) pp.8-17 < https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1043&context=momentum> [accessed 14/01/2019]

Clements,Ron.John Musker, dir,. Moana, (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2016).

Disney UK,COCO | Dante’s Lunch… A Short Tail | Official Disney Pixar UK | Official Disney UK, YouTube, 29 March 2017 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6rOKoa6RSHM> [accessed 14/01/2019] .

Docter, Pete, dir,. Up(Walt Disney Pictures Motion Studios, 2009).

Ghirlanda, Stefano. ‘Dog Movie Stars and Dog Breed Popularity: A Case Study in Media Influence on Choice’, Public Library of Science, 9.9 (2014) pp.1-5 < https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0106565&type=printable> [accessed 14/01/2019]

Lasseter, John, dir,.Toy Story,(Buena Vista Pictures Distribution, 1995).

Lawrence, Michael.‘Practically infinite manipulability’: domestic dogs, canine performance and digital cinema’, Screen, Vol.56. (2015) pp.115-120 <https://watermark-silverchair-com.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/hjv009.pdf?token=AQECAHi208BE49Ooan9kkhW_Ercy7Dm3ZL_9Cf3qfKAc485ysgAAAlswggJXBgkqhkiG9w0BBwagggJIMIICRAIBADCCAj0GCSqGSIb3DQEHATAeBglghkgBZQMEAS4wEQQMftCOKc7q12jbKLLbAgEQgIICDgcmzpiS5wJvETkfdgRbG_8ufMBaTWnJ18TTmyqAN1YY-EdhJqLBXDc4jhIXjZze5QwkhBJyn335VAqtc-PAu3j6aDgHerUJ6hRcVuZO5Fkvy4ztOLJUbrA_tptd-Jg8Nm0swbtwsfLDECNJxEQi-d2TepNcnnzFs01lonad20wHevwNEwt4dI4PcFhzXpr-QnKcT4FgZ4qA2nInrPh48yTkwQKtXRjTyR50LaqNRXPxvD_clBXKXds4zElyJFm1ekq8Aq2KE2IColkcDQeQyRtBegfRhqfW7Mc1MYk2ySssXwddj4PiA1Mz8XsC0P8UhpFvrK6Er1mOE0XY2xZWY0MW78V50tzGwobuPMxCnSC-yX0CkWxhpTD9wG2y5_oQ1tIctCQOs6cVqxPFSC_WKAzEHn4VQwaX8MuRvHOo1zWepH6E47aaP-0ToxVpNe5gk__tVRU7Sy2x9yDP8SBQcKvb8Sl6QwuqHIcYWaG9tEU8aL-iNF1xBsqIE4Ye6-H-eukI7EGW7RCjMSR8RZn_6394Dpj9CBLdzyrxb7RwHZ7FyC1kcaTbcoFCSOC9QJUZWDTkfol65i-0HZ-K0WnfGK8qYBI3-CN5YvhvfwCLeuXTfsPX7dCE9TuhHhlZabAxtmf7d8ADaLntIO3rJLrG6nJ65IeimX-M2ir-UJDIy2jv9-dSV3NsKeRGvLHhc68> [accessed 14/01/2019]

McLean, Adrienne L.. Cinematic canines : dogs and their work in the fiction film,

(Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey. 2014)

On the Set Coco [Dante (Xoloitzcuintli or Xolo), online video recording, YouTube, Feb 14, 2018 < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kOV7uzrsp7o&t=153s> [accessed 14/01/2019].

Robinson, Joanna. ‘Pixar Introduces Coco’s Lovable Dog With All-New Short’, Vanity Fair, 29 March 2017 < https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/03/coco-pixar-short-dante-dog-xolo> [accessed 14/01/2019]

Romey Kristin. ‘This Hairless Mexican Dog Has a Storied, Ancient Past’, National Geographic, 22 December 2017 <https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/11/hairless-dog-mexico-xolo-xoloitzcuintli-Aztec/> [accessed 14/01/2019]

Sohn, Peter, dir,.The Good Dinosaur, (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2015).

Unkrich, Lee, dir,. Coco, (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2017).

Watkins, Gwynne. ‘New Pixar Short “Dante’s Lunch” Introduces ‘Coco’ Dog, Plus Director Lee Unkrich on Whether ‘Coco’ Will Make You Cry (Exclusive)’, Yahoo, 29 March 2017 <https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/new-pixar-short-dantes-lunch-introduces-coco-dog-plus-director-lee-unkrich-on-whether-coco-will-make-you-cry-exclusive-155901674.html> [accessed 14/01/2019] .

Wearden, Grace. ‘Mirrors & Windows: Why Diversity Must Be Better Represented in Children’s Fiction’, Jameson First-Year Writing Contest Winners, 3.1 (Spring 2018). <https://journals.wheaton.edu/index.php/wheaton_writing/article/view/527> [accessed 14/01/2019]