Howard Hawks created a mass of parallels between the female and the leopard Baby in Bringing Up Baby. He displays a classical Hollywood screwball gender notion – women are wild while men are sensible. It is obvious that the female protagonist Susan has a closer relationship with the wild animals than everyone else in the film. In many scenes, Susan is even suggested to be the wild animal itself. Using the relationship of Susan, Baby and David, Hawks prompted us to reevaluate the potential of female animality.

This idea is most bluntly displayed in the scene when Susan and David go to the wilderness in search of Baby the leopard. The frame shows that David leads the way and Susan follows him behind, she finds the bushes too high that they obstruct her way and suddenly Susan walks on all four limbs and crawls on the forest ground.

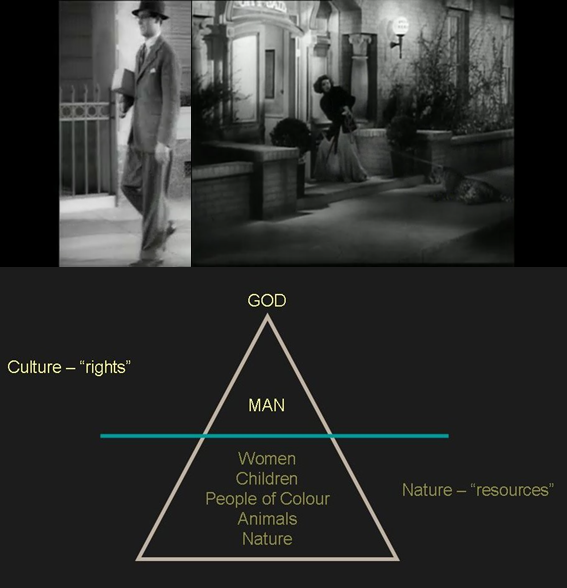

(Clockwise from the upper left: Fig. 1. Susan walking on all four limbs, Fig. 2. Susan looking up to David, Fig. 3. David and Baby in the same frame, Fig. 4. David looking down on Susan)

First, Susan shows physical animal instinct with slapstick. She feels easier to walk in the nature with four limbs than two in the wilderness, unlike David, who gets through the bushes just fine. Second, Susan’s verbal response also exhibits her animality. When David looks back and cannot see Susan at the eye level, he impatiently shouts ‘Susan, I have no time to play games!’ she plainly replies ‘I am not playing games.’ Susan’s answer suggests her animalness. The literal meaning of ‘not playing games’ is Susan admitting frankly that walking on all four limbs is a natural behavior to her. The man, however, can only see it as a game. Third, the manipulation of camera further attributes to her animalness perceived by audiences. Although they are not captured in the same frame, their positions and the discrepancy of height are shown through eye line matching. Moreover, the shooting angles tilt to imitate their subjective view, the camera looks down on Susan and looks up to David. Not only does it show the human and animal relation, it also reflects the social positions of male and female. The staged physical movement, dialogues and camerawork clearly identify David as a man and Susan as an animal. If we look at the last frame (fig. 3.) where David and Baby are captured in the same frame, David remains in the same position as the previous three frames (fig. 1,2,4) while Susan and Baby replace each other. Susan occasionally acts as the animal’s substitute in the film.

(Fig. 5. Susan dragging baby on the street)

A similar frame composition appears again in the film with a switch of roles where Susan becomes the master visually in the frame as she drags the real animal behind her. When set in an urban landscape and dressed in a rather manly blazer, Susan can finally dominate the animal instead of being the animal herself. (Fig. 5.) While the leopard here is the wild one from the zoo, Susan in comparison is the tamed and cultured one. The scene proposes that women have two ways to beat their wild selves, either learn to be the human in the civilised world, or try looking like men. A three levels of hierarchy is seen if we put the two frames together: men are always the well-polished and mannered human in the light, women are sometimes the animals and sometime the human, and animals remain wild at all times. (Fig. 6.) We would end up with men on top of women on top of the animals, a simplified version of the concept of ‘natural hierarchies’, which developed back in the classical and medieval period to justify rights of power to exploit ‘natural’ recourses in the world. (Fig. 7.)

(Fig. 6. David, Susan and Baby, Fig. 7. Illustration of The Great Chain. Taken from human-animal-liberation.blogspot.hk/)

Most films marking this hierarchy in the modern times would most probably be criticised as misogynistic as the women’s humanity and dignity are both physically and allegorically undermined. The sentiment is however only valid based on the assumption that animals are inferior beings. Nonetheless, in romantic comedies, romantic love is the final measurement of the characters’ capability instead of their intelligence or civilisation. Baby the matchmaker and the animalistic Susan are the ones who effectively set up the romantic plot in the film and bring out the romantic side of the emotionally oppressed David, leading the film to a happily romantic ending. Hawks’ representation of romance does not belittle wildness at all, it ultimately celebrates animality in characters and criticises the level headed.