Derek Cianfrance’s 2011 feature film, Blue Valentine, explores the instability of the family unit in the rural American suburbs. The almost immediate death of the family dog Megan underpins this instability as her absence becomes symbolic of marital collapse. Through two temporally separated narratives, the film observes the story of Dean, Cindy, and their daughter, Frankie. After Frankie finds Megan missing in the opening sequence, the film follows the subsequent twenty-four hours, moving between past and present to explore the conditions of Dean and Cindy’s relationship. Megan’s absence stands out; her death comes to represent the breakdown of the present, gravely antithetical to the romantic and distant past. Destabilising the security of the nuclear family, the departure of the loyal family pet becomes analogous of Dean and Cindy and an irrevocably damaged relationship that can no longer be saved.

The film plays with various images of isolation and detachment, underpinned by Megan’s death. Opening with Frankie alone in the garden (fig. 1), it cuts between different domestic spaces, with Dean asleep alone on the sofa (fig. 2) and Cindy in the bedroom (fig. 3). These varying degrees of separation immediately establish a chain of fractured relationships that comes to define the focus of the film. Where in the rest of the film a diegetic soundtrack is frequently used to connect Dean and Cindy through music, particularly in its documentation of the origins of their relationship, this opening sequence is almost silent apart from the sounds of birds in the distance, indicating the tone of present day, as the audience watches in eerie silence. This use of diegetic sound ties to the film’s distinct use of poetic and observational realism, where the camerawork and sound choices implicate the viewer into the family’s dysfunctional reality. These technical and stylistic choices are illustrated in figures 1, 2 and 3, where rather than placing us in a more traditional spectral position, the camerawork imposes us into the personal lives and spaces of the family, fitting the film into a canon of realism.

Figures 1, 2 & 3. The film’s opening sequence establishes a fractured family underpinned by Megan’s absence.

The scene of Dean burying Megan continues to underscore the image of a divided family. This sequence is foregrounded as narratively symbolic through temporal shifts that establish a binary between the interwoven nostalgic past and a damaged present. The shots cut in quick succession from the first time Dean sees Cindy in a care home in Pennsylvania (fig. 4) to the present, where Cindy looks on at Dean (fig. 5), holding the body of Megan, placing her gently into her grave. These shots connect an unseen period through the mirrored shot of the characters looking on at each other. Megan’s death connects the past to the present, reminding the characters of what they have lost.

Figures 4 & 5. Dean sees Cindy for the first time years before, cut with Cindy looking on at Dean burying Megan years later.

As Dean sits on the sofa watching an old home video of Frankie and Megan playing in Megan’s pen, the shaking camera and bad-quality video and audio create heightened nostalgia to build on the theme of a distance between past and present that continues to widen (figs. 9, 10 & 11). The image of the dog as the ultimate symbol of loyalty in these home videos, crucial to the family unit, reflects the couple’s inability to remain loyal to each other, as the film concludes with their separation ending with a shot of Dean, alone, walking away from Cindy and Frankie. Susan Mchugh’s foundational book, Dog, explores the socio-historical relationship between humans and dogs and the importance of the domesticated dog in helping to establish a family unit. Writing on the history of the bred dog, Mchugh underlines the breed-dog as ‘a carefully controlled site through which increasingly middle-class, heterosexual, white and Anglo-American ideals are reproduced’. With Megan’s death, Cianfrance underlines the unstable nature of these ideas and turns the pet into a narrative tool embodying failure by not appealing to these hegemonic ideas. Where McHugh underlines the occurrence of social reproduction reflected in the process of breeding dogs and their role in cementing Anglo-American socio-cultural familial organisation, her writing becomes reminiscent of tensions in the film surrounding biological reproduction as the audience learns Frankie is not Dean’s biological child. Where the dog’s death means a literal break in reproduction through an impossibility of breeding, Megan also becomes a marker of the threat divorce poses to the reproduction of the family in a social and biological sense.1 Domestic instability is echoed in the relationships of Cindy’s parents and Cindy and Deans own marriage is embodied in Megan’s death, Frankie’s nonconsensual conception and the film’s overall concern with marriage as a fragile institution.

Figures 9, 10 & 11. Dean sits on the sofa watching home movies of Megan and Frankie playing.

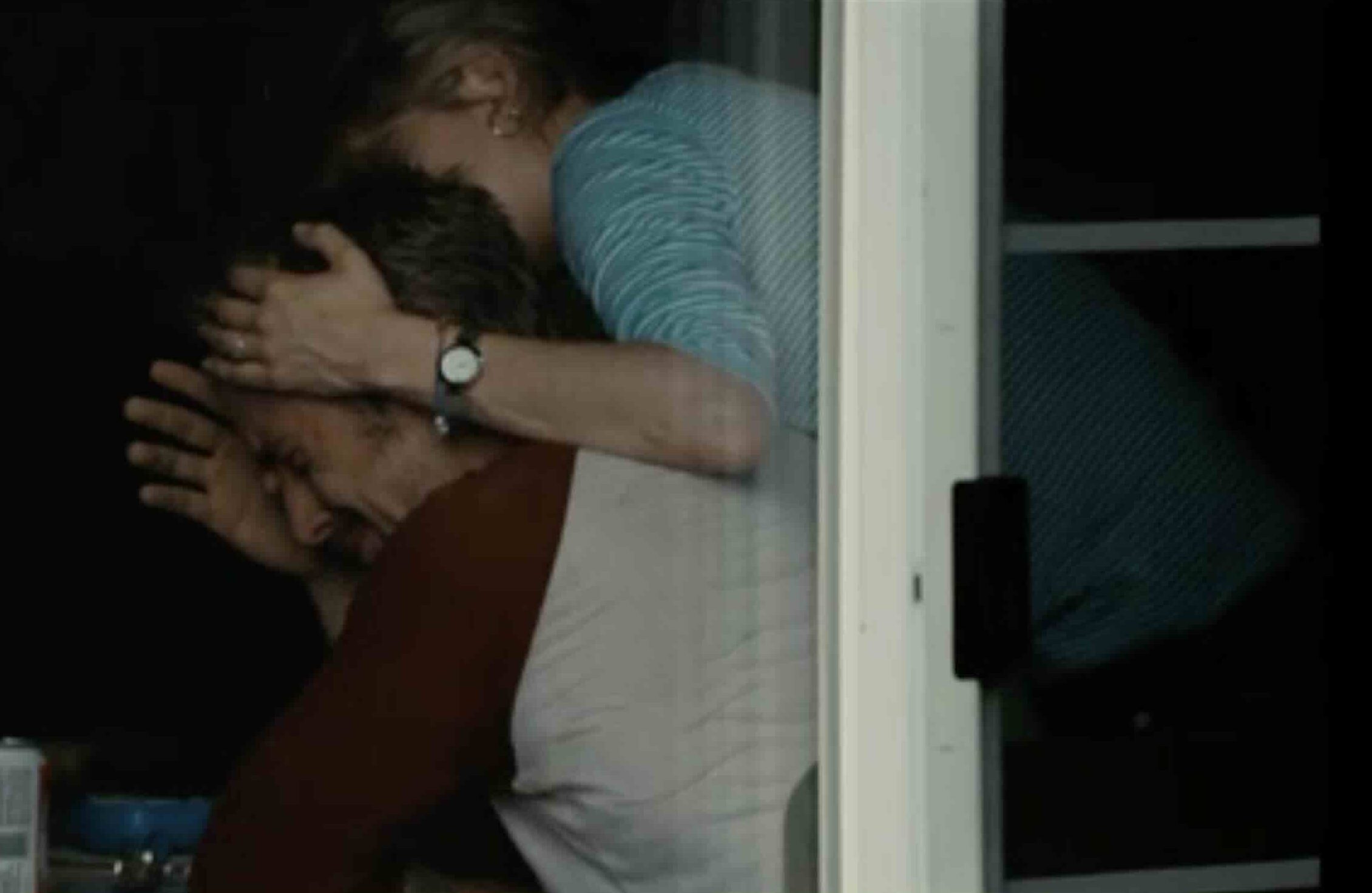

Figures 6, 7 & 8. Cindy finds Megan dead on the side of the road, Dean carries Megan to be buried, cut to Cindy comforting Dean.

Playing with notions of obedience and loyalty to the hegemonic reproduction of family, patriarchy and standards of success, Megan’s death and departure from the domestic setting encourages the audience to question the stability of the ideal suburban family. The death of the obedient dog asks us to question our own obedient loyalty within domestic structures. Megan’s position ultimately works to develop an image of impossible stability and inevitable collapse; her death symbolises the unsavable, foreshadowing Dean and Cindy’s separation and the fracturing of the family home.

- Susan Mchugh, Dog, (London: Reaktion, 2004) pp. 106 ↩︎

Bibliography:

Cianfrance, Derek, dir., Blue Valentine (The Weinstein Company, 2010)

McHugh, Susan, Dog (London: Reaktion, 2004)