Core to Mark Jenkin’s 2019 film, Bait, is a narrative depicting the gentrification of the coastal land and community in Cornwall. Following Martin, a local fisherman, Jenkin’s film emphasises how the tourism industry alienates and disenfranchises localised heritage and livelihoods. Martin’s job is central to this. The fish and lobsters that he catches serve as images that reflect Jenkin’s focus on class consciousness as tensions between Martin and the Leigh family, landlords that bought and rent out his childhood home to holiday makers, bubble to the surface of a narrative defined by opposition. Martin’s day is depicted through imagined binaries embodied by aquatic animals, from catching fish on the beach at first light, to gazing at the product of his labour half eaten by sightseers in the pub he drinks at in the evening. While Martin gifts his neighbours free fish, hanging them over their door handles, the film’s tensions boil over when Martin’s catch is stolen by the Leigh family’s son.

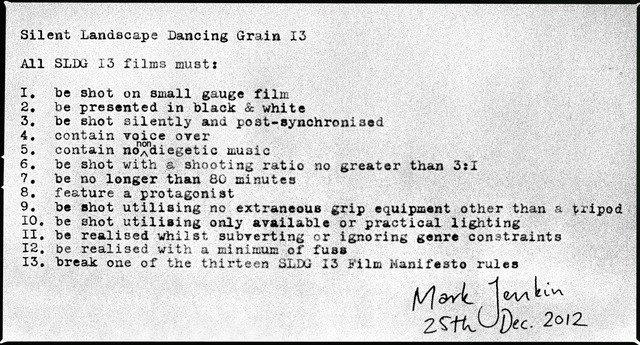

The film is described by its producers as a “handmade feature film”[1]. In accordance with his ‘Silent Landscape Dancing Grain 13’ manifesto, Jenkins shot with a windup camera, developing the film with unconventional materials such as vitamin C powder and coffee. As such, the film’s realism is best defined as experimental, with pastoral authenticity set against a narrative backdrop of consumerism. Jenkin’s editing furthers this, with abrasive cross cutting creating contention between images throughout the film. While subverting the cinematic “impressionistic realism”[2] of rural British narrative cinema, Bait doubles-down on the genre’s interest in socioeconomic disparity and how animals can serve as symbols of human behaviours. This isn’t dissimilar to other social realist filmmakers, like Andrea Arnold and Clio Barnard, who display “an attentiveness to the non-human animals with which we share our environments”[3]. Subverting this however, Jenkin’s fish and lobsters are defined by objectification and monetary value.

As such, the film’s themes lend it well to a Marxist reading wherein it displays many of the behaviours described in Karl Marx’s ‘Estranged Labour’[4]. In discerning the film’s aquatic animals as objects of labour, Jenkin’s film reveals itself as a narrative defined by alienation, objectification, and estrangement. Marx emphasises how “the worker can create nothing without nature, without the sensuous external world”[5]. Jenkin’s film extends this evaluation, questioning the consequences of when the sensuous external world is not only the “material on which his labor is realized”[6], but itself a profitable commodity. This is manifested in the various ways the film depicts fish, whether that be as sources of income or as markers of wealth and class. Foundational to this is Marx’s definition of the central binaries of society, detailing the “property owners and propertyless workers”[7]. These dynamics are sewn into the framework of Bait, with the Leigh family having bought Martin’s childhood home to rent it out to holiday makers for profit. They adorn the property with nets, buoys, and a porthole window in an “appropriation”[8] of Martin’s tools of labour. Fundamental to this, Jenkin’s film follows a tight structure centred around the journey of the fish from capture to plate. This narrative reveals at lengths the alienations as described by Marx in ‘Estranged Labour’, representing product alienation, “species-being”[9] alienation and the estrangement of man from mankind.

To begin the narrative of the fish’s journey, Jenkin foregrounds the labour that goes into catching them early in the film. He does this through close-up shots of the sharp netting and dead fish lay out across the shore as Martin and his nephew wake up at “first light” to work.

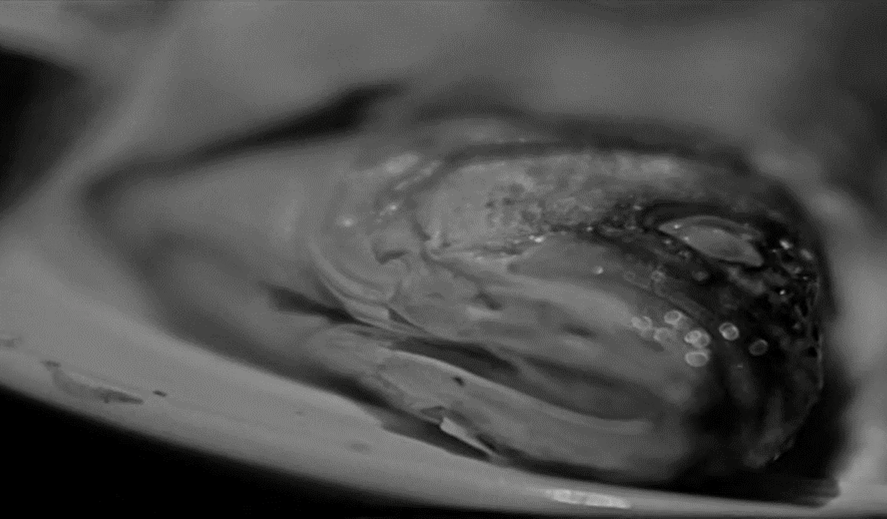

Strikingly, Jenkin often depicts the fish in close-up shots that put their eyes in the centre of the frame. These shots are evocative of the film’s genre, operating within the conventions of realism wherein images “linger” and create a “dynamic subjectivity between looker and image”[10]. This is particularly poignant due to the film’s monochrome shading, where the black pupils of the fish’s eye contrast deeply with that of the white surrounding it. While the result is disturbing, it resonates with a reflection upon Marx’s understanding of mankind’s estrangement from his “species-being”, wherein nature is an extension of the human body. Drawing upon Marx’s description of nature as “the inorganic body” [11]of humanity, Jenkin’s macabre emphasis on the fish’s eye reflects an urgent link between the tensions rising between the humans of the film and the ecological crisis that sets its backdrop. This consumes Jenkin’s diegesis as well, where outdoor scenes are flooded with the sounds of thrashing waves and indoor scenes are often coupled with the voices of radio hosts discussing the consequences of Brexit and the debate surrounding fishing in the Channel. Yet, Martin’s line of work is dependent on his estrangement from nature. As detailed by Marx, “estranged labor estranges the species from man” wherein “nature is his body, with which he must remain in continuous interchange if he is not to die”[12]. As the fish’s eye stares back at the camera lens, Jenkin beckons for a discussion of the climate crisis that threatens coastal communities such as the one depicted in his film.

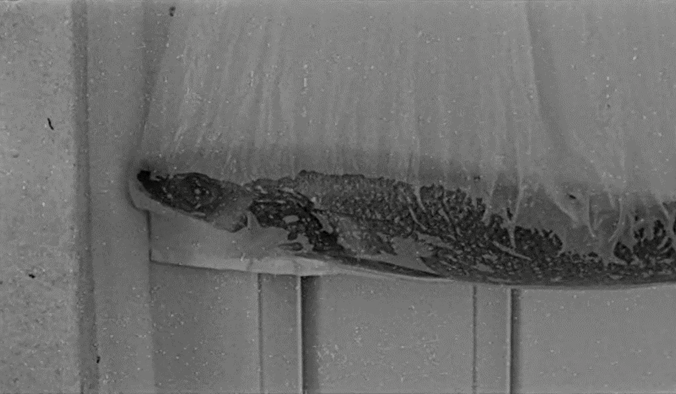

Jenkin’s film has a clear understanding of the hierarchies that arise within the social strata when nature is appropriated in this manner. Marx described the alienation of man from one another, wherein when the worker “treats his own activity as an unfree activity, then he treats it as an activity performed in the service, under the dominion, the coercion, and the yoke of another man”[13] which itself is a core builder of tension and antagonism in Bait. In these instances, Jenkin urges his audience to revaluate their relationship not only with nature, but also with each other. The acquisition of fish in the film serves as a larger metaphor for the ways in which man treats one another as well as a signifier of class and wealth. In the first instance, Martin is emphasised as the base of the infrastructure that upholds many of the area’s local businesses. After having shown Martin catching the fish, Martin is seen selling them to the owner of the pub in the community. She scoffs at the inflated prices of his produce. In comparison, Martin gifts those who live nearby to him fish for free, placing them on the handles of their front doors in plastic bags.

Again, Jenkin allows these shots to linger, as the transparency of the bag set against the wet fish reveals its eye. Martin’s own community values are called into subject here, as this small action signifies a rebellion of the caring nature to the existing capitalist hierarchy and the consuming gentrification of his neighbourhood. It’s notable that in this shot, as compared to one of the fish tangled in the netting, the whiteness of the bag and door are striking compared to the dark shade of the fish. In this sense, Jenkin inverts his focus from nature itself, as called into question by the fish’s eye in the former shot, to the ways in which nature effects mankind in the latter. Moments like these in the film are particularly striking when considering scenes such as the following one where Martin is sat in the aforementioned pub.

Jenkin’s mise-en-scene situates Martin sat next to a sign that reads, “Tonight’s Special, Seabass, Caught in This Very Cove!”. The prestige of selling locally caught fish in parallel with the reality of the labour that goes into farming them results in a dark comedic irony. As Martin drinks, he notices opposite the family currently renting his family home eating the fish he caught the prior morning and sold to the pub owner. He is confronted with the fruits of his labour being consumed by those who have partaken in the gentrification of his heritage. This scene exemplifies Marx’s statement that “the more the worker produces, the less he has to consume; the more values he creates, the more valueless, the more unworthy he becomes”[14].

The scene ends with Jenkin allowing the camera to linger on the half-eaten fish’s eye left on the plate. Here, in considering William Epson’s writing on “proletarian art”[15], parallels can be drawn between Jenkin’s film and that of John Grierson’s Drifters. Like how the fish serve as a poignant reminder that the film has the same “pastoral feeling about the dignity of that form of labour”[16] as that of Grierson’s, Epson notes that “Herring fishermen are unlikely to see Drifters; for all its government-commercial claim to solid usefulness is it a ‘high-brow’ picture”[17]. In this sense, while Martin’s labour is understood to be dignified in the film, he is unable to partake in the same culture of which he serves. All the while, in serving this culture, Martin partakes in the demise of his own. This paradox is the epitome of Estranged Labour, summarised by Marx as the truth that while “labor produces for the rich wonderful things ]…] for the worker it produces privation”[18]. In considering this alongside the conventions of the social realist genre, it signifies a broader issue that while “realist texts might speak of the nation, they do not speak to it”[19].

When fishing seabass proves financially disappointing for Martin, he turns to catching lobsters. The film’s tension, as caused by the repeated alienation of Martin from both his local community and heritage, boil over as the Leigh family’s son steals Martin’s lobster to impress his parents. What follows is a sequence of cross-cutting between the family’s preparation of the lobster, Martin confronting their son in the pub and the making of pasta by Martin’s nephew. The sequence is accompanied by a quiet diegetic soundscape, interrupted only by the sounds of voices, the boiling of water and eating noises. What has previously only been contention manifested through passive aggressive acts turns into action, as Martin forces Hugo to repair the lobster trap he vandalised in order to steal. There is duality within the lobster’s imagery here, as both an image of higher-class delicacy and a tangible image of what labour, capitalism and gentrification has stolen from Martin. Central to this is the question as to who is entitled to this animal and catch? Martin, as the individual who lay the foundations for the capture of the lobster, or Hugo, as the one who seized the opportunity to claim the animal in a self-fulfilling act? The abrasive cross-cutting within the scene therefore determines a clashing of ideals, wherein the multitudes of images of what Cornwall and the coast means to local people and what it has come to represent are encapsulated by the lobster.

To summarise, Mark Jenkin’s Bait considers aquatic animals and their commodification through a narrative framework of tourism and capitalist profiteering. In following the journeys of fish from capture to plate, through labour that “appropriate the external world”[20], the film explores what Marx describes as “estrangement, as alienation”[21]. Jenkin does this through understanding that the idealisation of the coast boils down to the existence of aquatic animals in a pastoral environment that can generate profit for humans. He also considers that this happens at all levels of the social strata, both through the proletariat act of fishing and the ownership of property.

Jenkin uses striking images, such as that of the dead fish, and draws upon the social realist genre more broadly to provoke his audience into reconsidering how they partake in the consumption of these animals, as well as the wider impact this has on communities such as the one Martin lives in. In evoking Marx’s Estranged Labour, I argue that the portrayal of alienation reveals these consequences as the source of the growing tensions in the film. To summarise using Marx’s words, the film exemplifies how man “transforms his advantage over animals into the disadvantage that his inorganic body, nature, is taken from him”[22].

Further Reading

David Forrest, Social Realism: art, nationhood and politics (Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013)

John Bellamy Foster, Marx’s Ecology (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000)

Samuel Hanes, Teresa Johnson and Cameron Thompson, ‘Vulnerability of fishing communities undergoing gentrification’, Journal of rural studies, Vol 45, (2016) p. 165-174

The Last Tourist, dir. Tyson Sadler (Elevation Pictures, 2021)

Bibliography

[1]Jonathan Romney, ‘Bait’, Sight & Sound, September 2019, pp. 50, 50-51

[2]Jonathan Romney, ‘Bait’, Sight & Sound¸ September 2019, pp. 50, 50-51

[3]Michael Lawrence, ‘Nature and the Non-human in Andrea Arnold’s Wuthering Heights’, Journal of British Cinema and Television, 13.1 (2016) 177-194 (p. 177) <https://doi.org/10.3366/jbctv.2016.0306>

[4]Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Martin Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto (New York: Prometheus Books, 1988)

[5]Marx, Engels, and Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto p. 42

[6]Marx, Engels and Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, p. 42

[7]Marx, Engels and Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, p. 41

[8]Marx, Engels and Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, p. 49

[9]Marx, Engels and Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, p. 45

[10]David Forrest, New Realism : Contemporary British Cinema (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020) p.75

[11]Marx, Engels and Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, p. 45

[12]Marx, Engels and Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, p. 45

[13]Marx, Engels and Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, p. 47

[14]Marx, Engels and Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, p. 43

[15]William Epson, Some Versions of Pastoral (London: Chatto & Windus, 1935) p. 3

[16]Epson, Some Versions of Pastoral, p. 8

[17]Epson, Some Versions of Pastoral, p. 8

[18]Marx, Engels and Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, p. 43

[19]David Forrest, New Realism : Contemporary British Cinema, p.3

[20]Marx, Engels and Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, p. 49

[21]Marx, Engels and Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, p. 42

[22]Marx, Engels and Milligan, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, p. 46