Prior to American Honey, Arnold’s filmography was distinctly British, primarily focused upon the harsh reality of poverty in Britain. However, American Honey deviates from this pattern, as it follows protagonist Star (Sasha Lane) on her journey with a travelling magazine sales crew across America. Star dices with danger, leaping headfirst into risky situations, whether it be jumping into cars with several different men, or pursuing a relationship with Jake (Shia Labeouf) against the rules of the magazine crew. This unnerving behaviour a reflection of the bleak truth that, as an impoverished runaway, Star has nothing to lose. Unfortunately, Star’s story is not one of success. Her sales are minimal, and she appears to move from one dangerous scenario to another. American Honey is littered with images of vastly different kinds of animality, for a far greater purpose than merely their aesthetic beauty. Whilst animals are not the central focus of Arnold’s film, she presents animal and human life as indivisible. Arnold draws distinct similarities between free and restricted kinds of animality, reflecting the struggles of American Honey’s young characters.

American Honey primarily fits within the road movie genre, a genre considered as an integral part of American culture. Arnold uses the potential of the road movie and its tendency to romanticise alienation in order to explore the relationships and seclusion of humans and animals alike.[1] Road movies are usually concerned with misfit groups following a pursuit of freedom, in which the road becomes synonymous with self-discovery, and at times, chaos. American Honey adheres to these conventions as Arnold focuses upon humans trying to escape their past. In this way, the sales crew pursue a thwarted version of the American dream. This idea of freedom and escape is used to highlight disparities of situation between human and non-humans within the movie. The varying terrain of America becomes a landscape of staggering inequality as the film traverses vast open fields, rich neighbourhoods, and impoverished towns. This setting provides the perfect canvas for Arnold’s renowned focus upon animal subjects. Arnold uses sporadic images of free and restricted animality, illustrating the fraught tension in which Star and the magazine crew are seemingly free on their adventure road journey, yet inherently restricted by their estranged and poor identity. Moreover, Star’s hardened characterisation is challenged by her compassion towards the animals which surround her, directly juxtaposing her distinct distrust of humans.

The vehicle is a key setting within road narratives and American Honey is no different. The minivan is home to young people from all walks of life, and animals become equal and integral parts of this mismatched group. As Star is introduced to each member of the crew, she is also introduced to one boy’s pet flying-squirrel. The boy, Sean, tells Star, ‘She fell out of a tree’ and ‘Her name is Sugar’. Star is introduced to the animal here in the same way as she is to each crew member. Whilst Sean’s explanation that ‘she fell out of a tree’, attempts to justify his pet keeping as an act of compassion or saviour. This notion infers that the animal has been rescued, in a similar way to the other young adults have been rescued from poverty and swept up into their journey with the sales crew. This idea is revisited elsewhere later in the film as a dog, Bella, is brought into the van. The two teens laugh retelling the story of how they stole the dog. The dog is aligned as merely another crew member, sitting between members in the crowded van as they kiss and stroke her. They teens laugh saying ‘Now she’s ours. She’s our dog now. Nobody’s ever gonna get her back cos she’s gonna be the new dog’. Continuing to say, ‘Listen, dog, you’re gonna be a stoner by the time it’s over […] Can we get the dog high?’. For Star and her peers there appears to be no bridge between themselves and the animals they bring into the van. Neither the people or the animals are immune from the landscape of crime and drug abuse which characterises Star’s journey. Arnold appears to be saying something deeper here, suggesting that although the animals are taken under good intentions, this lifestyle can be pollutive and damaging for non-human and human travellers. The animals become trapped within this confined space and are restricted in the same way that these young adults are restricted by their economic circumstances.

Figure 3: Bella surrounded by drug use

Figure 2: The misfit magazine crew

Whilst animals are an integral part of the life of these underprivileged characters, Arnold presents pet keeping and affection towards animals as a universal behaviour. At a crucial point in the film, Star abandons Jake in pursuit of adventure, jumping into a car with rich men to accompany them to a BBQ at their large country house. Star fires questions at the men, asking, ‘Is this your dog? Is this your house?’. There is a childish curiosity here, overwhelmed by the privileged surroundings which starkly contrast the dingy spaces which Star inhabits on the road. Shaky handheld camera movements track Star’s point of view as she moves with awe through the house, lingering over a framed painting of a horse hung upon the wall. Star moves through to the terrace where an over the shoulder shot follows Star’s focus upon horses grazing freely in a nearby field. This brief focus aligns these animals with the wealth and privilege of the rich men. Star’s attention to these animals, and equally these rich older men adorned with cowboy hats, is similar. There is an awe of wonderment to her focus upon their representation of a foreign way of life.

However, Star’s focus does not remain upon the horses for long. Sitting on the poolside the camera refocuses upon a wasp floating in the water. Star quickly fishes the insect from the water using a torn sweet wrapper saying, ‘I gotcha’. This marks just one of the several moments in the film in which Star stops to aid faltering animals. In Pamela Hutchinson’s reflections on American Honey she notes, ‘Arnold’s cut-in shots of butterflies, birds and bugs failing to take flight reinforce the feeling that something is keeping these young Americans down. Only Star pauses to set the bugs free’.[2] There is a feeling that Star too is waiting for someone to save her. Even within this privileged setting, with alcohol, money, and rich men to distract her, Star’s focus remains on the small, everyday animal. This focus draws connections to Arnold’s award-winning short film entitled Wasp. The aptly named short film culminates in a wasp crawling into the mouth of a neglected child. This focus upon a commonly disliked animal across Arnolds cinematography works to create a connection between her interest in the underprivileged in society and under-represented animality. Moreover, Star’s urge to help those suffering is revisited throughout the film, whether it be through saving a drowned wasp from the pool or providing food to the young children whose mother is incapacitated by drugs. Therefore, Arnold draws an explicit similarity between the vulnerability of animals and people.

Figure 4: Star rescues wasp

Figure 5: Star allied with the bear

Often, when humans alienate Star, she seeks refuge in the natural world. When Jake abandons Star following an explosive argument, she escapes to the outdoors for solitary reflection. The camera angle shifts to show a large bear within striking proximity. The moment is serene as Arnold foregrounds the diegetic sounds of nature and the bear. Even as the bear approaches Star, the teenager remains unphased despite her vulnerability. This moment challenges typical representations of bears as a threat, portraying Star and the bear in a quiet companionship. This interaction is almost downplayed by its subtlety, however this representation of oneness between Star and the natural world is poignant. This subdued, calm representation of Star is in stark contrast to her confrontational behaviour towards humans within the film.

Further to this, American Honey draws connections between people and animals not merely through ideas of vulnerability, but through a shared wildness. Jake defends Star when she is reprimanded for her poor sales. He tells Krystal, the leader of the sales crew, ‘I’m good with the wild ones’. Star is animalised here as Jake presents her as something that must be tamed and controlled. Later wildness also becomes and indicative trait of Jake’s character as he howls like a wolf in order to attract Star’s attention. Star reflects on his actions later stating, ‘you make a good wolf […] you were the only wolf’’. This analogy draws upon the discourse surrounding wolves which represents wolves as definitively wild pack animals. However, Star and Jake symbolise the lone wolf analogy somewhat as they unsuccessfully attempt to break away from the crew. Once more, ideas of animality are useful in understanding the ways in which Star, Jake, and the remainder of the crew, function as a group of misfits, slightly disconnected from civilised society.

These ideas of wildness are reaffirmed through the group’s unruly behaviour at the ‘loser night’ celebrations, in which the members of the crew with the least sales fight one another. One crew member wrestles fiercely, pouncing stark naked and covered in dirt, beating his chest in anticipation. Animal characteristics are projected onto this young man, othering the chaotic behaviour of the fellow group members in their representation as animalised humans. Arnold presents this chaotic event as animalistic through incorporating representations of raw aggression, and foregrounding ideas of wildness. Moreover, Bella the dog, playfully attempts to engage in the chaos, echoing the childlike excitement of the group as they gather to watch the fight. Bella’s incessant barking works alongside a heavy rap song, creating a tribal energy. This uncivilised representation of the sales crew furthers portrayals of the marginalised youngsters as wild. They are separated from a civilised reality here, occupying a kind of radical freedom that the road narrative allows.

The final scene furthers these ideas of revelry as the magazine crew dance wildly around a campfire. Jake pulls Star to the side and places a turtle into her hands. This ambiguous gesture has a curious intimacy. Star turns her back on Jake, and the party, moving towards the water to set the turtle free. The camera slowly lingers over the turtle returning to its natural habitat, before Star too enters the water. Although we have already learned that Star is unable to swim, she submerges herself as Arnold appears to suggest that Star, like the turtle, has turned away from the group towards a more natural safety. When Star emerges from the lake the music is abruptly cut and only the natural diegetic sounds of birds and insects remain. This moment is something of a rebirth. As Savina Petkova notes, Arnold’s characters ‘reinvent themselves physically, as female, as animal, as human’.[3] Fireflies and small bugs flit around Star in the darkness and it becomes apparent that suddenly she is alone. Star is at peace among this natural environment and there is a notion that, like the animals she seeks to rescue along the way, Star is saving herself.

American Honey works to establish a distinct disparity between captive animality, for example the trapped insects, and dogs within vans, and an arguably more natural, free animality such as the bear and the horses. Star and several of the other young travellers embody these ideas of freedom and restriction at various points within the film, through their alternating wild and vulnerable representations. Whilst the road movie genre offers a radical space in which these characters are imbued with a sense of freedom and wildness, they are ultimately restricted by systemic boundaries of class which inhibit their actual freedom.

Figure 6: Example of wildlife cinematography style

Arnold intertwines images of humans and animals within American Honey to expose inequality and disparities across America. Whilst moments in the film can be likened to wildlife cinematography, and synonymous with the freedom and beauty of nature, other aspects of animality in the film are overtly obscure, such as a dog roaming a motel parking lot, dressed in a makeshift cape and shorts. This variation shows how animals too can be marginalised and confined. Ultimately, Arnold shows an unfiltered view of humanity, however, this is only achieved by illustrating how ideas of freedom and restriction transcend beyond the human world.

Bibliography

A24, American Honey Official Trailer HD A24, online video recording, Youtube, 21 June 2016, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y1SpWZm1PLc&feature=youtu.be> [accessed 20 May 2020]

Cohan, Steven, and Hark, Ina Rae, eds., The Road Movie Book (London: Taylor & Francis E, 1997)

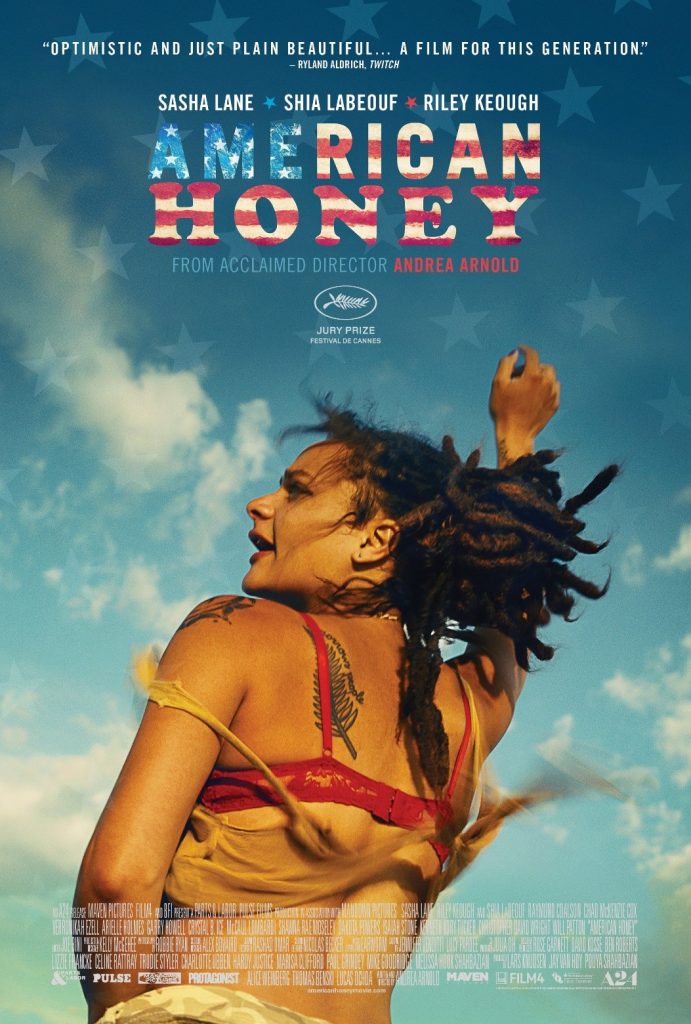

Figure 1, digital image, imdb.com, <https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3721936/>[accessed 25 May 2020]

Figure 2, digital image, rogerebert.com https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/american-honey-2016https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/american-honey-2016 [accessed 25 May 2020]

Figures 3-6, print screen digital image, Box of Broadcasts, <https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/ondemand/index.php/prog/0E44AEC6?bcast=131448478> [accessed 27May 2020]

Hutchinson, Pamela, ‘American Honey’ Sight and Sound, November 2016 <https://search-proquest-com.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/docview/1833966739?accountid=13828> 66-67 [accessed 20 May 2020]

Petkova, Savina, ‘Female Beasts: Animalistic Sexuality in Fish Tank and American Honey’, Girls on Tops, 2019 <https://www.girlsontopstees.com/read-me/2019/4/6/andrea-arnold-and-the-female-beast-animalistic-sexuality-in-fish-tank-and-american-honey> [accessed 05 May 2020]

Filmography

American Honey (dir. Andrea Arnold, 2016, USA, UK)

Further Reading

Lawrence Michael, ‘Nature and the Non-human in Andrea Arnold’s Wuthering Heights.’ Journal of British Cinema and Television, 13.1 (2016), 177-94 http://dx.doi.org/10.3366/jbctv.2016.030

Petkova, Savina, ‘Female Beasts: Animalistic Sexuality in Fish Tank and American Honey’, Girls on Tops, 2019 <https://www.girlsontopstees.com/read-me/2019/4/6/andrea-arnold-and-the-female-beast-animalistic-sexuality-in-fish-tank-and-american-honey> [accessed 05 May 2020]

Priest, Joy, ‘American Honey’ Southern Cultures, 24. 2 (2018),146-147 https://doi.org/10.1353/scu.2018.0025

Urbina, Ian, ‘For Youths, a Grim Tour on Magazine Crews’, The New York Times, 21 February 2007 <https://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/21/us/21magcrew.html> [23 May 2020]

[1] The Road Movie Book, ed. by Steven Cohan and Ina Rae Hark,(London: Taylor & Francis E, 1997) (p.1).

[2] Pamela Hutchinson, ‘American Honey’ Sight and Sound, November 2016 <https://search-proquest-com.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/docview/1833966739?accountid=13828> 66-67 [accessed 20 May 2020] (p.67).

[3] Savina Petkova, ‘Female Beasts: Animalistic Sexuality in Fish Tank and American Honey’, Girls on Tops, 2019 <https://www.girlsontopstees.com/read-me/2019/4/6/andrea-arnold-and-the-female-beast-animalistic-sexuality-in-fish-tank-and-american-honey> [accessed 05 May 2020].