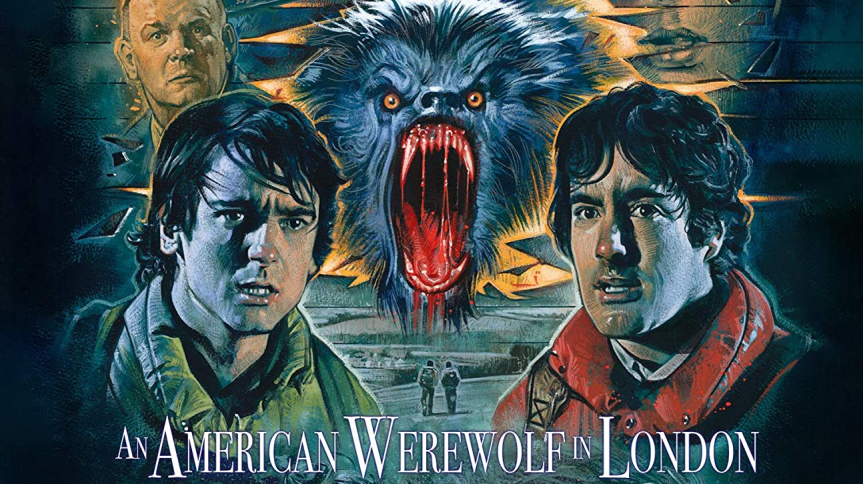

“The wolf’s bloodline must be severed; the last remaining werewolf must be destroyed. It’s you David.”

An American tourist, traumatised and alone wakes up in a London hospital after an attack on the Yorkshire Moors. His newly cursed body drifts between human and wolf as his deceased friend haunts him in limbo, telling him he must kill himself for the good of others. The people around him deny his story, claiming he was attacked by a lunatic and simply traumatised while the nurse manages to convince him that he isn’t a werewolf. Even the head Doctor who is explicitly told by a man on the Moors, ‘it’s almost full moon… he’ll change’, underestimates the result of the attack. It isn’t until his transformation in the middle of London square that people finally listen, but it’s too late for David Kessler – our American Werewolf in London.

Figure 1: David declares to nurse Alex that he’s a werewolf.

Figure 2: Moor resident warns the Doctor that David will ‘change’ at full moon.

Figure 3: David’s death

David’s naked form, riddled with bullets, is the last shot of the film before the credits abruptly roll to the sound of The Marcels’ Blue Moon. What emerges from John Landis’ concoction of self aware jokes, stunning practical effects and horrifying transformations is a tale of neglect and the question of animal euthanasia as we use this final shot to reflect on the rest of the film and consider: was death the only solution?

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

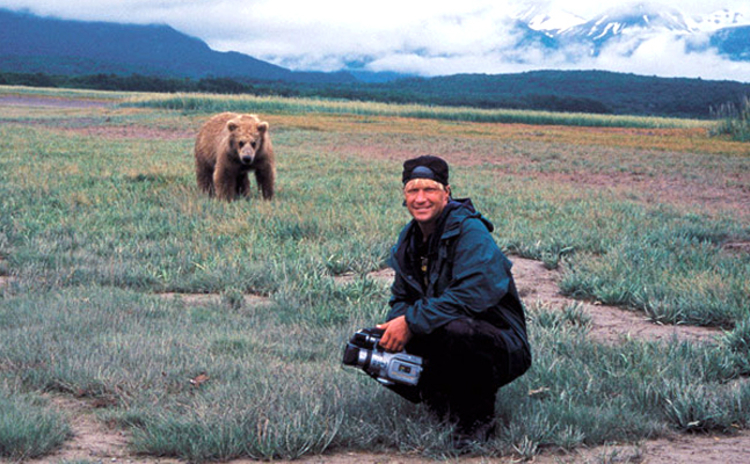

David’s portrayal of becoming a wild animal, or simply non-human, can be seen during one of his visions at the hospital, which harbours a nature-documentary style chase [figures 4-7]. Viewers see him running barefoot and naked across the forest and there is a wide shot of the marsh, marking out his ideal territory. A tracking shot is then used to bring viewers with him as he effortlessly manoeuvres across the terrain and there is a close up shot to his feet – a David Attenborough-esque way of demonstrating the biological tools he uses to peruse the habitat. As he reaches the two deers, he hides behind a tree and a medium shot reveals the doe’s ear alertedly twitching. An extreme close up shot of David’s eyes widening is then used to show his excitement for the prey, as he lunges forwards and takes it by the neck – feasting on its head. Though emblematic of his now predatory and animalistic identity, it is also mimetic of the way humans viewed and treated him throughout the film. As opposed to portraying him in his wolf form, Landis’ decision to keep him as a human highlights the way the people of London disregarded his behaviour, admitting at various points that he was a dangerous werewolf, and instead focusing on the fact his outer appearance was still human by their standards.

Figure 8

Figure 9

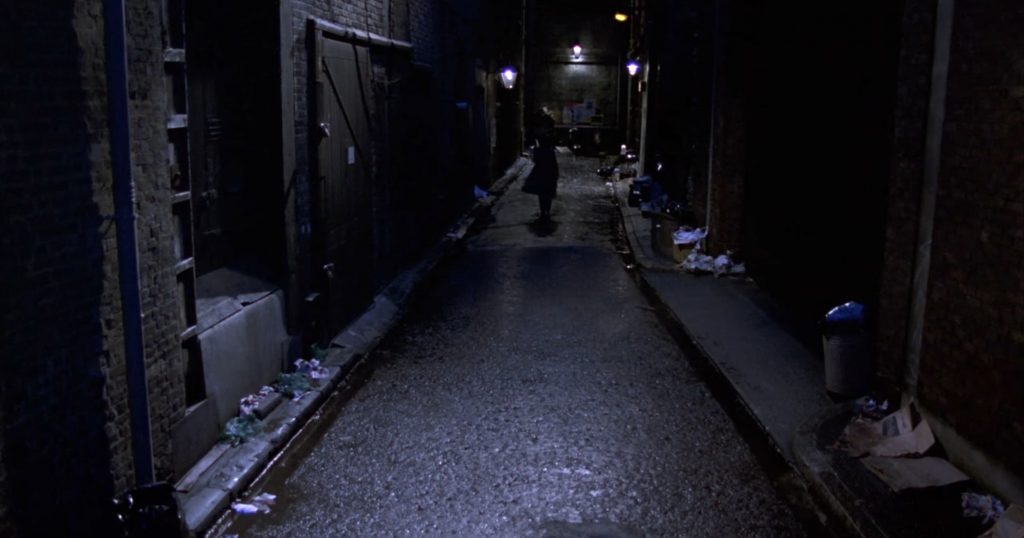

David’s predisposition to transform into a wolf every full moon is completely against his will – part of his innate nature. Unfortunately, he isn’t granted the luxury of anything but death; his penultimate demise – put down in an alleyway by the police – is a tragedy which sees him transform back to his naked form, reminding the audience that he was once a man, once living and once demanded for nothing but understanding and help. It is a tragedy which extends beyond cinema, to a real world where animals are punished for the behaviours and decisions of humans [figure 8 – 9]; Travis the chimp, once considered ‘a beloved animal and a local fixture’, was killed and branded vicious upon attacking a woman he did not recognise; he was frightened and was never supposed to be kept as a pet. [2] This notion of animals having to suffer from acting upon their instincts is emphasised by the parallel of David’s wounds and the placement of blood in his dream sequence [figure 10-11].

Figure 10

Figure 11

Here, the use of visual design and makeup depicts blood from his prey splattered across the right of his shoulder, his lower face and hands while his left shoulder remains completely clean. This parallels the patterning of his wounds, shown in a medium shot as the doctor begins a checkup [figure 11]. The placement seems to evoke a sense that as a werewolf, David – in this human society – will bring harm to himself if he is to act on his carnal instincts which lay dormant until the full moon.

Doomed to death if he feeds himself during wolf form, the decaying ghost of Jack and many other victims continue to visit David with only a single, morbid solution for him.

“Have you ever talked to a corpse? It’s boring! I’m lonely! Kill yourself, David, before you kill others.”

Griffin Dunne as Jack Goodman

The dialogue is both comical yet tragic, with an emphasis on Jack’s own feelings as a human as opposed to David, who must now exist as half human, half nocturnal predator. It is a solution which provides for human convenience only, disregarding him as a beast – even Jack’s comfort as a ghost is considered more valuable than David’s life. Lycanthropy is a curse, a predisposition and isn’t necessarily the current holders issue but they must suffer for it. The solution and pressure for death is forced by humans.

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

This strong, human narrative and control over David’s animal perceptions is also prevalent within his death scene. With the animalised David backed into an alleyway, there is a wide shot of his nurse, Alex, running down towards him. The scene then cuts to a medium shot of her from the front angle, revealing a crowd of officers backed behind her. The distance represents David’s detachment from society with Alex as his only barrier. Wether or not he can cross back into society is determined by a complete human. A low volume, extra diegetic sound begins to play in an ominous hum as the intra diegetic pleas from Alex begin to unfold. ‘David… please, please let me help you’, she states. With the final words from that utterance, the extra diegetic hum fades out and there is a close up shot of David in his wolf form. The scene falls silent besides his low growl and with a final attempt Alex decides to say ‘I love you David’. The absence of extra diegetic music (often used to indicate tone in the scenes) plunges viewers into a state of tension, unable to predict what will happen next. This is an effective technique at emphasising the barrier between human and animal perceptions – they are unpredictable for us who don’t completely understand them, and so can we really decide their fate? David shows a brief moment of recognition as another extreme close up shot shows his snarl slightly relaxing, before lunging at Alex. The officers unload and London is filled with the sounds of hundreds upon hundreds of bullets against a single wolf.

Figure 15: David Kessler’s wolf form movie prop (Credit: Tom Spina Designs)

Figure 16: The bipedal werewolf Larry Talbot in ‘The Wolf Man’ – a much more human depiction than David Kessler (Credit: Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images)

It’s important to note that David did not attack right away, only when spoken to and confronted up close when his territorial instincts as a wolf-creature were activated. This reflects the unfortunately common, real world issue of humans disregarding animal space and nature – causing them to be considered harmful by putting their own human presence there. What is most striking about this death sequence is what it reveals about human nature; even when faced with an animal being, humans will always assume that human recognition is what determines wether it is a monstrous beast or not. If a shark kills a seal, is it branded a seal-eater? What does it really mean for an animal to be a man-eater?

In addition to this, the layered sound of hundreds of guns firing highlights the existing power difference between the single werewolf, which was close to a large bear [figure 15], and an entire police force. This emphasises the fact that the humans had the power to have a choice, thus they had the capabilities to look for alternate methods. However, due to him being perceived as an animalistic beast which they couldn’t understand, they decided to kill him. His death and the situation could have been avoided completely if the humans had taken action sooner and listened to David’s concerns.

Figure 17

Figure 18 (credit: @BenjaminTobitt on Twitter)

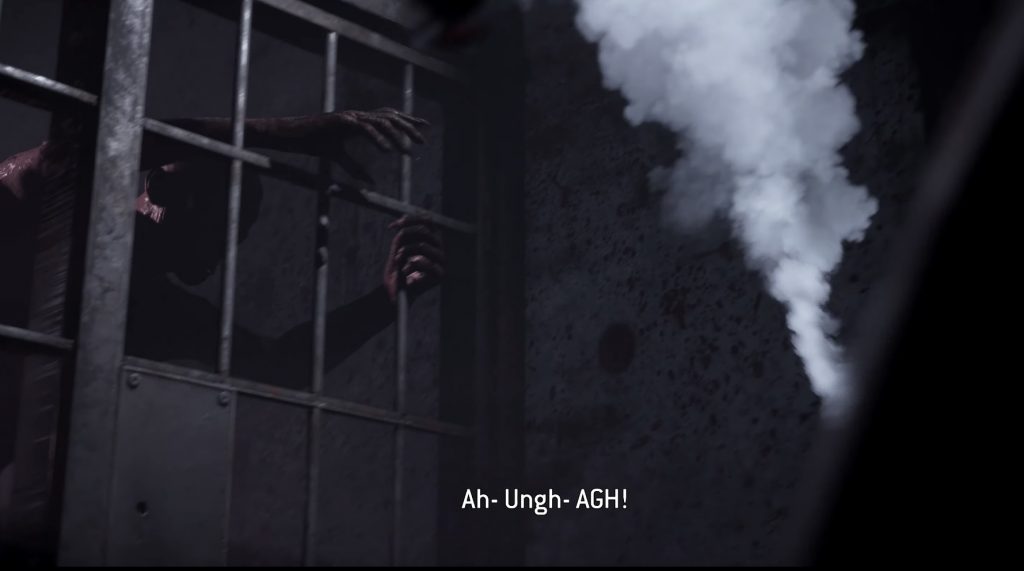

Figure 17-18: A screen capture and concept art from Supermassive’s The Quarry game. Werewolves and those suspected of the curse were locked before a full moon with one werewolf character even being able to maintain his job as a youth camp advisor on regular nights – they were able to co exist to an extent.

Once again, David’s unfortunate death can be used to reflect on earlier in the film, right to when the pub goers of The Slaughtered Lamb gave their very first warning to the backpacking duo.

Stay on the road. Keep clear of the moors. Beware the moon, lads.”

The dialogue reveals, though subtlety, that although the people around the Moors are aware of the danger, they are still able to function like usual, implying that they have indeed been co-existing with this creature. Their advice seems to claim the Moors as the territory of the wolf man, one which they do not cross upon either. It isn’t until David and Jack trail off the path, into the wolf’s territory, that they must interfere. And so the fate which eventually befalls David, is inflicted on the werewolf which came before. After the attack, David turns to his side and there is a medium shot of an older man in place of the wolf, his eyes wide with shock and his torso torn with bullets [figure 19] – a direct parallel to David’s morbid end. Perhaps the curse wasn’t in the lycanthropy, but the continuous neglect from humanity.

Figure 19

To conclude, David’s declarations and the warnings of others fell on deaf ears until the screams of his victims in London square rang out. The euthanasia of animals is often a topic of debate but what does it say about human and animal boundaries? If one takes in a traumatised dog and cannot provide it with the patience and guidance it needs, why must the animal suffer? If a human steps into a ‘wild’ animal’s territory and is attacked, why is the creature immediately considered a danger to all humans and hunted down for acting naturally? David, like many other animals, had a predisposition. The doctor and employees at the London hospital were warned many times; even David’s rampage around an officer demanding he himself be arrested for the murders failed and the Doctor leaves the Yorkshire Moors after being told ‘it’s almost full moon – he’ll [David] change’. Instead, they dismiss the gravity of the situation and then, when he finally attacks, he gets put down. He was doomed because people didn’t listen, a fate shared by many animals – domesticated and wild. A fate shared because humanity valued its own convenience above others.

Bibliography

An American Werewolf in London, dir. by John Landis (Universal Pictures, 1981)

[1] BBC Earth, Best Wild Animal Chases Part 2, compilation, YouTube, 18 February 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZYbyaj4G9FM> [accessed 15 January 2023]

[2] Oconnor Jessica, ‘Inside Travis The Chimp’s Gruesome Attack That Left A Woman Without A Face’, ATI, 2022 < https://allthatsinteresting.com/travis-the-chimp> [accessed 15 January 2023]

Supermassive Games, The Quarry (2022), Playstation

The Wolf Man, dir. by George Waggner (Universal Pictures, 1941)

Further reading:

Aaltola, Elisa, and John Hadley, Animal Ethics and Philosophy : Questioning the Orthodoxy (London ; New York: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2015)

Cujo, dir. by Lewis Teague (Warner bros, 1983)

Pluhar, Evelyn B., Beyond Prejudice : the Moral Significance of Human and Nonhuman Animals(Durham: Duke University Press, 1995)

Sorabji, Richard, Animal Minds and Human Morals : the Origins of the Western Debate (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1993)

The Wolf Man, dir. by George Waggner (Universal Pictures, 1941)