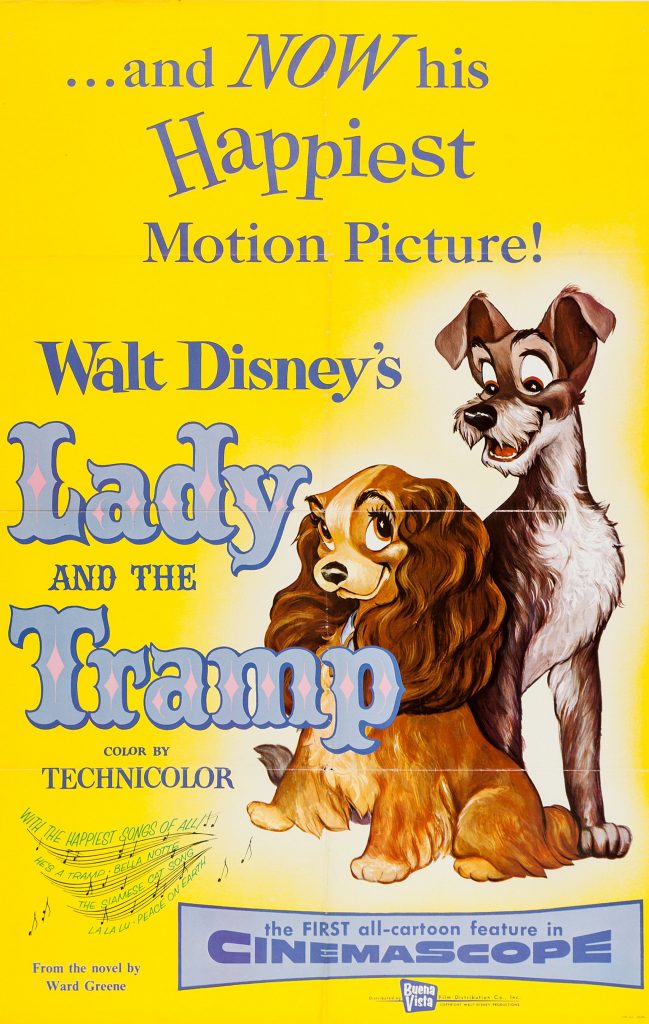

Disney’s 1955 film Lady and the Tramp follows its two title characters, a pampered American Cocker Spaniel named Lady and a stray mongrel referred to by the dogs about town as ‘the Tramp’. Lady’s indulgent upper class life is disrupted when a baby arrives in her house. When Aunt Sarah comes to babysit with her malevolent Siamese cats in tow, Lady finds herself muzzled and turned out on the street. Luckily for her, the streetwise Tramp comes to her rescue and shows her how he lives, ‘footloose and collar-free’. The sheltered Lady finds it difficult to keep up with the Tramp’s carefree and lawless lifestyle, and after she is caught by the dogcatcher and impounded, an unpleasant conversation with the town’s street dogs reveals to her the Tramp’s womanising ways. In the film’s dramatic climax, the Tramp must find a way to prove himself to Lady and demonstrate that despite their opposing lifestyles, they are in fact compatible for one another.

Lady and the Tramp is produced in the hand-drawn method of animation that Disney is famous for, and falls under the category of an animated film. Animation is arguably ‘a film technique’ rather than its own genre but often incorporates ‘genre-like elements’, in this case from romance and family films. [1] Romance films typically focus on the journey that a relationship between two main characters takes, and they often ‘face obstacles and hazards’; in Lady and the Tramp these obstacle take the form of differing social class status between the pedigree Lady and the stray Tramp, who has a lax attitude to relationships and commitment. [2] The film focuses on importance of commitment and family life, told through the medium of animal relationships, to teach moral lessons on loyalty, courage and friendship as well as presenting the middle-class American dream as a goal for all to aim for regardless of their social background. Although it contains a villain and very mild horror-like elements in the form of the rat that sneaks into the baby’s bedroom with malicious intent, its absence of violence, inclusion of moral lessons and ultimate happy ending with the ‘triumph of good over evil’ places it firmly within the family film genre. [3]

Lady and the Tramp contains two of Disney’s most controversial characters in the form of Si and Am, Aunt Sarah’s Siamese cats that perpetuate many racist stereotypes of Asians. [4] An influx of Asian immigrants into America in the twentieth century created a fear of the disintegration of American society and a desire for ‘America [to] be kept American’ expressed explicitly by Present Calvin Coolidge. [5] American labourers resented Asian immigrant labourers, who they felt undercut wages and took jobs that were not rightfully theirs and the National Origins Act of 1924 almost entirely barred Asian immigrants from entering the United States. [6] The portrayal of Si and Am corresponds with these contemporary anxieties of ‘yellow peril’. Although not the villains of the film, they are certainly antagonistic and portrayed as manipulative and sly, never once expressing positive characteristics. They move in perfect symmetry, lacking individuality whilst plotting to steal the baby’s milk and attempt to eat a pet fish and budgerigar and display total disregard to the damage they cause to the family home, embodying the negative attitudes towards mass Asian immigration and the damage they are doing to American society by ‘stealing’ jobs that should be rightfully American. This attitude is further expressed through the lyrics to their infamous song, where they state: ‘now we’re looking over new domicile/ If we like we stay for maybe quite a while’, with the new domicile of Lady’s home being an allegory for the American state which they will take for their own with disregard to the opinion of the original inhabitants.

Si and Am speak in stilted English with heavily exaggerated accents and have buck teeth with a distinctive slant to their eyes, physical aspects that perpetuate unattractive negative Asian stereotypes. Significantly, they are characterised as cats as opposed to one of the many Asian dog breeds. This creates a difference of species between the heroic Lady, who is a specifically American Cocker Spaniel (as opposed to the more widely recognised English Cocker Spaniel) and the unfriendly antagonistic cats, implying that Asians are a distinct and undesirable kind of ‘Other’ from white Americans, as well as associating Asians with less-desirable characteristics that are usually associated with cats. These characteristics include unfriendliness, independence, vicious and lazy, which also directly contrasts with the positive and desirable attributes often associated with dogs such as loyalty, compassion and protectiveness. This racist portrayal of Asians is especially controversial as it comes from within a film that is marketed at children. Children become aware of skin colour and physical differences from a young age, but build their ideas about racial identity socially. [7] The develop their ideas about racial identity from the opinions of those around them as well as their own personal experiences and exposure to media, which is why it is important that they are not exposed to prejudices that may develop into strong racist viewpoints later in their lifetimes. To include such an incredibly racist and stereotypical portrayal of Asians in a film marketed at children and families shows complete disregard for the way in which this portrayal will shape children’s understandings of Asian culture and ‘moulds their brains early on to perceive anyone of Asian descent as bad’, or could be argued to be a deliberate attempt by Disney to impose these racial attitudes upon children. [8]

Lady and the Tramp expresses issues of social class and inequality through its canine characters, which fall into two distinctive categories – upper class, pedigree dogs and stray street dogs who find themselves impounded. The street dogs, representative of the working class, such as Peg the Pekingese, Bull the Bulldog and Pedro the Chihuahua are portrayed as friendly but all posses ‘degenerate’ and undesirable characteristics. These include Pedro’s apparent drunkenness, Peg’s seductive swagger and Bull’s loud and mocking Cockney accent. The street dogs of the lower social class are confined to the Dog Pound, and the film never resolves whether or not they manage to escape. Their imprisonment and the film’s lack of concern for their fate demonstrates a social disregard towards the lives of the working class and an association between negative characteristics and the working class. In contrast, Lady the American Cocker Spaniel displays demurity and Trusty the Bloodhound and Jock the Scottie display gentlemanly valour, desirable characteristics that are reflective of the upper-class refined neighbourhood they live in and portrayed as an ideal to aim for; the admiration of Lady’s collar and license by the other dogs in the Pound is a canine embodiment of the American Dream and a desire for a stable family life and home.

The Tramp is immediately established as being from the wrong side of the tracks; his introductory scene shows him sleeping by a railroad and the name given to him by the other dogs shows his vagrancy. He is obviously a mongrel which further highlights his lower position in society. He is the archetypical loveable rogue who is proud of the fact he is ‘footloose and collar-free’ without an owner, but emphasises the fact that he does not belong anywhere. Drawing Lady into his lifestyle results her being impounded, an allegory for the corrupting influence of men on young women and the degenerative effect of vagrancy on American society. The romance between the Tramp and the pedigree Lady which cumulates with his adoption shows a desire for upwards social mobility, particularly as the Tramp takes great pride in the red collar and license that he wears in the final scene. Their puppies are presented biologically inaccurately which represents a fantasy of social agreement where although the Tramp has been able to lift himself from vagrancy to a higher social class, his blood physically remains the same and cannot ‘mix’ with Lady’s upper-class status. They have four puppies; three spaniels and one mongrel which physically represent the permanent difference that will exist between Lady and the Tramp.

Lady and the Tramp is quite clearly stylistically told from a dog’s point of view; the human characters have simplistic names (‘Jim Dear’, ‘Darling’, ‘Aunt Sarah’) that give them little sense of identity and their faces are rarely shown. Instead, establishing shots are animated as being from ‘dog level’ – below tables and at the bottom of fences, and with humans differentiated by their shoes and legs. The dogs all display loyalty towards family and friends as a moral message in the desirability of this characteristic; Lady’s friends valiantly defend her, Tramp sets his friends free from the Dogcatcher and the dogs in the Pound work together to try and escape. In the dog world, the canine characters live together happily despite their differing social statuses, with even Boris the Communist wolfhound being portrayed as friendly despite contemporary Cold War anxieties. [9] The utopian dog world allows for differences and co-existence, but Disney does little to disguise the racial and social prejudices it expresses in even its friendly characters.

Lady and the Tramp’s theme of family loyalty is common to many of Disney’s films. 101 Dalmatians and The Aristocats both feature a narrative family protection and the importance of staying together, as well as a stable home embodying middle-class values. Similar issues of social class and mobility are expressed in Oliver & Company, where a homeless kitten joins a gang of dogs to help him survive before he is adopted by a rich family living on Fifth Avenue. Racist stereotypes of Asians can also been seen in other Disney films. A Siamese cat in The Aristocats plays the piano with chopsticks and sings ‘Shanghai Hong Kong egg Foo Young, fortune cookie always wrong’ in an exaggerated accent and is depicted with slanted eyes and bucked teeth, and the Siamese Twin gang from Chip ‘n’ Dale Rescue Rangers are portrayed as criminals who also speak with a heavily distorted accents. [10]

Lady and the Tramp’s theme of family loyalty is common to many of Disney’s films. 101 Dalmatians and The Aristocats both feature a narrative family protection and the importance of staying together, as well as a stable home embodying middle-class values. Similar issues of social class and mobility are expressed in Oliver & Company, where a homeless kitten joins a gang of dogs to help him survive before he is adopted by a rich family living on Fifth Avenue. Racist stereotypes of Asians can also been seen in other Disney films. A Siamese cat in The Aristocats plays the piano with chopsticks and sings ‘Shanghai Hong Kong egg Foo Young, fortune cookie always wrong’ in an exaggerated accent and is depicted with slanted eyes and bucked teeth, and the Siamese Twin gang from Chip ‘n’ Dale Rescue Rangers are portrayed as criminals who also speak with a heavily distorted accents. Racism in Disney is not just restricted to representations of Asian characters; there is a obvious absence of ethnic minorities throughout many of its films and those they are represented are often presented as villains or according to stereotypes (one of the most potent being the Native Americans/ ‘Red Men’ in Peter Pan). The company has only recently begun to acknowledge this and represent a wider range of races and ethnicities and attributing characters from ethnic minorities with positive characteristics.

Further Reading

‘Lady and the Tramp’ – https://www.timeout.com/london/film/lady-and-the-tramp

‘Lady and the Tramp: A Dog’s World’ – https://thedancingimage.blogspot.co.uk/2010/12/dogs-world-lady-and-tramp.html

‘Racism and Class Warfare Symbolism in Disney’s Lady and the Tramp film – https://illuminatiwatcher.com/racism-and-class-warfare-symbolism-in-disneys-lady-the-tramp-film

‘Siamese Cats in Lady and the Tramp’ – https://blogs.uoregon.edu/j320finalproject/2013/03/13/siamese-cats-in-lady-and-the-tramp

‘The Code Behind the Kitty: Unpacking the Racist Myth of the Siamese Cat’ – https://flavorwire.com/397512/the-code-behind-the-kitty-unpacking-the-racist-myth-of-the-siamese-cat

Referenced Material

Joel Bocko, ‘Lady and the Tramp: A Dog’s World’. The Dancing Image.

Hayley Brown and Morganne Hatfield, ‘Siamese Cats in Lady and the Tramp.’ Asian Americans in Media.

Tim Dirks, ‘Animated Films.’ AMC Filmsite.

Tim Dirks, ‘Children/ Kids and Family Films.’ AMC Filmsite.

Tim Dirks, ‘Romance Films.’ AMC Filmsite.

Ben Joseph, ‘The 9 Most Racist Disney Characters’. Cracked.

Sheryl R. Tynes, ‘The Colors of the Rainbow: Children’s Racial Self-Classification’, Sociological Studies of Children and Youth.

[1] Tim Dirks, ‘Animated Films.’ AMC Filmsite. https://www.filmsite.org/animatedfilms.html (accessed 23.11.2013).

[2] Tim Dirks, ‘Romance Films.’ AMC Filmsite. https://www.filmsite.org/romancefilms.html (accessed 23.11.2013).

[3] Tim Dirks, ‘Children/ Kids and Family Films.’ AMC Filmsite. https://www.filmsite.org/childrensfilms.html (accessed 23.11.2013).

[4] Graphic Design Degrees, ’10 Disney Characters who Stirred up Controversy’, Graphic Design Degrees, https://graphicdesigndegrees.org/10-disney-characters-who-stirred-up-controversy (accessed 31.12.2013)

See also: footnotes 8 and 10.

[5] Paul S. Boyer (ed.), The Enduring Vision: A History of the American People (6th edt.), (Wadsworth; Cengage Learning; 2010), p. 548.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Sheryl R. Tynes, ‘The Colors of the Rainbow: Children’s Racial Self-Classification’, Sociological Studies of Children and Youth 8, p. 72

[8] Hayley Brown and Morganne Hatfield, ‘Siamese Cats in Lady and the Tramp.’ Asian Americans in Media.

https://blogs.uoregon.edu/j320finalproject/2013/03/13/siamese-cats-in-lady-and-the-tramp (accessed 23.11.2013)

[9] Joel Bocko, ‘Lady and the Tramp: A Dog’s World’. The Dancing Image. https://thedancingimage.blogspot.co.uk/2010/12/dogs-world-lady-and-tramp.html (accessed 24.11.2013)

[10] Ben Joseph, ‘The 9 Most Racist Disney Characters’. Cracked. https://www.cracked.com/article_15677_the-9-most-racist-disney-characters.html (accessed 24.11.2013)