This wild land must be civilised.

Whilst this film’s premise – the child-friendly tale of two young werewolves attempting to end Oliver Cromwell’s invasion of Ireland – may sound bizarre, it proves itself to be one of the most politically and thematically poignant children’s films of 2020. The young protagonist is Robyn, an English Puritan and the daughter of famed wolf-hunter Bill Goodfellowe, who has found himself working under Cromwell in the town of Kilkenny. Early in the film, Robyn sees her dreams to follow in her father’s wolf-killing footsteps crushed, as shortly upon her arrival in Ireland she is turned into a ‘Wolfwalker’ (a mythical shapeshifter) after encountering the wild young Mebh Óg MacTíre in the forests. Her nightly transformation into an animal (and increasing dissatisfaction with Puritan life) slowly alienates her from her father and the Lord Protector’s regime, causing her to become embroiled in Mebh’s quest to save her native homeland. Working alongside Mebh and her pack of real (non-fantastical) wolves, they seek to liberate Mebh’s mother from Cromwell’s imprisonment and stop the advance of the English army.

Figure 1: The Secret of Kells poster

Figure 2: Song of the Sea poster

Figure 3: Wolfwalkers poster

An animated adventure film, Wolfwalkers is the third instalment of Cartoon Saloon’s ‘Irish Folklore trilogy’ – following The Secret of Kells (2010) and Song of the Sea (2014). Wolfwalkers shares not only its distinctive hand-drawn animation style with its predecessors, but also key thematic elements (including childhood, magic, shapeshifting, and the threat of some ‘other’ world). However, whilst all three films feature animal characters (and human characters who transform into animals), Wolfwalkers is the film that has the most to say about animality as a construct. All of the films formal elements -its animation style, its cinematography, its literary and sound design – work to collapse an assumed human/animal hierarchy, drawing numerous visual links between the human and animal characters and going so far as to include animal transformation as a metaphor for self-actualisation and freedom. The film itself seems to invite an anti-colonial message into this reading, as it is Oliver Cromwell’s authoritarianism and narrow definition of ‘civilisation’ which separates his human subjects from nature and (as illustrated literally through the film’s magical elements) from their own innate animality. As with all of Cartoon Saloon’s films, childhood is another major theme: with children being presented as the most attuned to the magical and animal worlds. In Wolfwalkers, we see very clearly how the Puritan government attempts to socialise this innate wildness and animality out of children (and the native Irish populace), separating them from – and then destroying – the natural world.

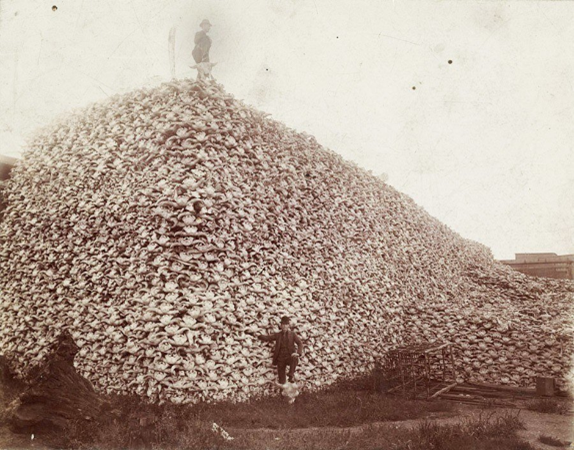

The clear link the film draws between colonialism and animal exploitation is by no means arbitrary: in fact, it references a long and sordid history of environmental and animal harm. As American settlers headed West in the late 18th Century, they slaughtered tens of millions of buffalo, driving the species to near extinction. The mass extermination of this species not only cleared the land, but was expected to solve the ‘Indian Problem’: knowing the Native Americans relied on the buffalo for meat, they claimed ‘Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.’[1] The extermination of both native people and native animals are here intertwined, both part of a singular mission of settler colonialism. This was by no means confined to America – the film is explicitly based on a very similar chapter in the history of Irish colonisation, which (alongside the various atrocities committed against the native population) also led to the extinction of wolves in the region. As director Ross Stewart recounts:

The Cromwellian forces were ordered to cut down so many forests because that’s where the rebels and the wolves were hiding out. There was a determined focus to make the wolves extinct. And then there was also this huge clash of cultures: You had this old Irish culture that was pagan, like you say, but also had a very strong matriarchal kind of emphasis. There were powerful women leaders, and there was a connection to nature, and there was more of a symbiotic relationship with living. And then this puritanical force came in and replaced it. And it was very much patriarchal. It was very much dominion over nature. And it was very much about taming the wildness, inside as well as outside.[2]

The film achingly deconstructs various binaries which, across history, have been hierarchies of power. Humans and animals, men and women, even coloniser and colonised: these struggles are interlinked, and equally founded in false divisions. As Wolfwalkers demonstrates, there is worth in every human being, just as there is an innate animality that connects us to both each other and the natural world.

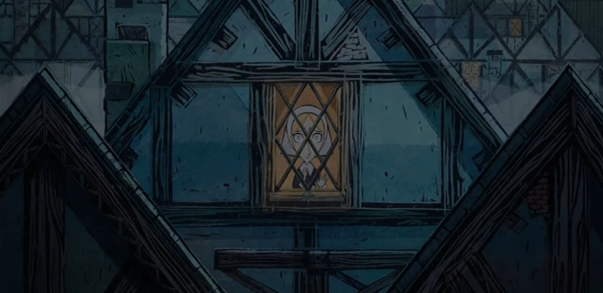

The oppressive weight of colonisation is visualised in the film through its animation and cinematography. The imagery of bars permeates the film’s depiction of the town, Cromwell’s Irish base and an essential prison for the native Irish people under his regime. This extends beyond the literal bars that block the town’s exit: the town’s geometric and angular architecture similarly evokes bars, and reflects the entrapment this version of ‘civilisation’ forces upon its citizens. This is juxtaposed by the forest, which is marked by its bright colours and gentle shapes. Even the linework is changed – an achievement made possible by the distinctive hand-drawn style Cartoon Saloon uses. As opposed to the very ‘clean’ and finished linework associated with the town and its inhabitants, the forest is characterised by rougher, sketchier lines, evoking freedom and movement. This extends to the characters aligned with the natural world – compare the linework of Robyn in figure 7, before and after she decides to stand up to Cromwell to defend the wolves.

Figure 5: Robyn’s window

Figure 6: Town’s walls

Figure 7: Robyn’s linework changes

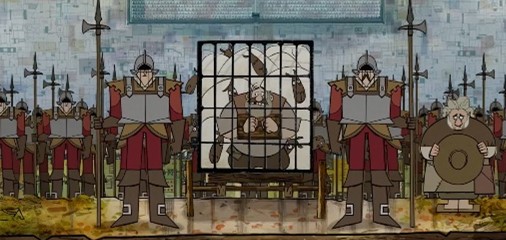

Not only does the forest evoke a sense of freedom and wonder, it is also strongly linked to Ireland’s native culture and Pagan heritage. Markings on the mountains reference traditional Pictish and Celtic imagery, and the Lord Protector explicitly states the region is ‘Pagan’. It is also clear that the Irish people in the town itself still associate themselves with this culture, but are forced by their English colonisers to abandon these beliefs and lifestyles. When Irish workers are sent to help destroy the forest, their dialogue informs us that they don’t want to do it, and that ‘it’s the soldiers making us’. The one Irish farmer who questions Cromwell is imprisoned with his sheep (figure 9): a visceral frame, with its imagery illustrating how colonial control of people and animals is one and the same. As the Lord Protector himself outlines, ‘this wild land must be civilised’, referencing both the rebelling Irish and the wolves.

Figure 8: Ancient symbols in the mountains

Figure 9: Farmer imprisoned

Figure 10: Bars of the town gate

The climax of the film similarly emphasises this link between the power structures. After Robyn and Mebh save the forest from Cromwell, the locals break free from the darkened bars of the town, and step into the glowing light of the Wolfwalker’s magic. Their faces rejoicing, one comments on the ‘lovely music’ of the wolves’ howls. The liberation of the forest’s animals has brought the liberation of the human-animals, and they stand in solidarity.

Figure 11: Town behind bars

Figure 12: Watching the wolves

Joanne Faulkner has suggested that to differentiate humanity from other animal species, we humans must differentiate ourselves from a ‘certain aspect’ of our own being; an animality and wildness adults have learned to suppress.[3] Children, she argues, still retain that untamed, unrepressed animality, and so the child ‘has come to represent the… animality adult humanity leaves in its wake, and which must be worked upon in order to create a better humanity.’[4] This link between childhood and animality is abundantly clear in the film, in which every child seems a little, joyously wild. This is perhaps why the Lord Protector keeps them caged up in town, proclaiming ‘no children beyond the walls.’ Despite the attempts of Puritan society to domesticate and ‘civilise’ these children, however, the boundary between them and wildness remains thin. This is perhaps why young Robyn – straining under the confines of Puritan life – is so easily transformed, quick to embrace her own inherent animality.

Embracing her innate animality and letting go of the false human/animal divide is the psychological stepping stone that allows Robyn to rebel against her society’s other unjust hierarchies, as she is able to overcome the patriarchal expectations of her gender and become instrumental in fighting the colonial system. Her ‘transformation’ into a wolf quite literally allows her to see the world differently: something the film hammers home by massively changing the visual style in scenes from wolf-Robyn’s perspective. When exploring her new and enhanced senses, Robyn tracks various animals in the forest – glowing neon outlines on a dark, minimalist background. This style emphasises the vibrancy of animal life in the forest, a prosperous eco-system Robyn had never noticed before (on her single-minded mission to hunt wolves, she had little time for other creatures). Being able to see the magic of the forest later inspires her to defend it, alongside the wolves she was once taught to kill. She’s also able to experience the fun and freedom of a wild animal, as she plays and chases the others in the pack. After a childhood in a strict Puritan household (which offered nothing to the young girl but domestic chores), she is able to fully embrace her own childishness and indulge the instincts she had to suppress in Cromwell’s ‘civilised’ world. The ‘running with wolves’ sequence beautifully expresses this sense of joy and spontaneity in all its technical aspects. Blending different animation styles, tracking shots, free flowing linework, and almost surrealist transitions, the visuals exude movement and playfulness. The sound design similarly marks this as a key moment of change in Robyn’s life and character: the non-diegetic ‘Running with the Wolves’ by Aurora plays, one of only two songs on the score not composed by Bruno Coulais. The energetic synth-pop is a stark contrast to the largely instrumental tracks used elsewhere in the film, highlighting the difference between the freedom and animality Robyn experiences in the forest and her strict life in town.

Figure 13: Wolfvision

Figure 14: At play

Figure 15: Transition shot

As well as her young age, it is apparent that her gendered experience of Puritan society played a role in Robyn’s drive to rebellion. Director Tomm Moore noted:

she met Mebh, who was from that kind of matriarchal pagan society, she was going to see a mirror of somebody – a young woman – who was allowed to live instinctually, where she was being told to keep it all repressed and to just stay down, keep her head down, work, follow orders and not break the rules.[5]

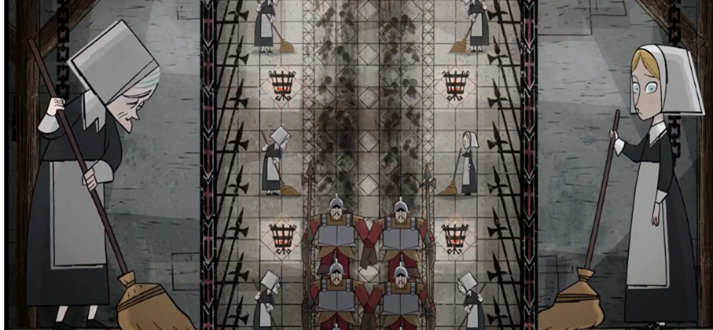

The film employs multiple techniques that express the drudgery and suppression women in Puritan society endured. This includes a split screen montage (again evoking the image of bars and chains) depicting the never-ending chores assigned to women in town – grey, isolating and endless. Forced into domestic service by Cromwell himself (an attempt to break her wild spirit and prevent her from exploring the forest), Robyn is assured by the menfolk that this is a ‘righteous life for a young lady’. As figure 17 demonstrates (a split-screen in which Robyn mirrors an older servant in Cromwell’s household), it is not just ‘young’ ladies who are forced into this soul-crushing, banal work, but all women in England’s patriarchal society.

Figure 16: Robyn’s chores

Figure 17: More chores

Figure 18: Wolf family reunited

This is in contrast to the depictions of Mebh and her mother, who are empowered by their own wildness and animality, and left both uncontrolled and uncontrollable.

The film ultimately emphasises the freedom that comes from accepting human animality, and embracing non-human animals. Collapsing the human/animal divide, the film emphasises themes of interconnection between people and the natural world with both mythic and ‘actual’ animals. The film’s depiction of the non-magical wolves is particularly poignant: an extinct species in Ireland, the playfulness and beauty of their on-screen depictions emphasises the tragedy of their real-life culling. Equally, the film reflects on the connection between children and animals – a long-standing convention that merges seamlessly with both the film’s themes and genre as a family-focused animation.

To conclude, Wolfwalkers is a deeply political film interested in the ways colonialism harms both the human and non-human world. It’s focus on such difficult topics as imperialism, ecological destruction, and patriarchy distinguishes it from typical children’s animation, and it explores those themes meaningfully. Whilst an ode to Irish history, it is equally reflective of the forms of neo-colonialism still in place in the modern world. From the Dakota Access Pipeline to the shipping of waste to developing countries, ecological damage is still being inflicted on historically colonised peoples, and Wolfwalkers is as relevant to today as it is to 17th-century Ireland.

Figure 19: Protest of the DAPL

Figure 20: Waste shipped to Indonesia

Footnotes

[1] J.W. Phippen, ‘Kill Every Buffalo You Can! Every Buffalo Dead Is an Indian Gone’, The Atlantic, 13 May 2016, <https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2016/05/the-buffalo-killers/482349/> [accessed 10 January 2022].

[2] Rebecca Alter, ‘Wolfwalkers Is Giving Kids a History Lesson on the Horrors of Colonialism’ Vulture, 18 February 2021, <https://www.vulture.com/2021/02/wolfwalkers-is-giving-kids-a-history-lesson-on-colonialism.html> [accessed 14 January 2022].

[3] Joanne Faulkner, ‘Negotiating vulnerability through “animal” and “child”’, Angelaki, 16.4 (2011), 73-85, <https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725X.2011.641346> (p.76).

[4] Ibid, p.78.

[5] Meagan Damore, ‘Wolfwalkers Creators Break Down the Film’s True Villain & Message of Tolerance’, CBR, 13 November 2021, < https://www.cbr.com/wolfwalkers-interview-tomm-moore-ross-stewart/> [accessed 14 January 2022].

Image Sources:

Figure 4: Gilbert King, Mountain of 19th Century Bison Skulls, digital photograph, Smithsonian, 17 May 2012, <Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed | History | Smithsonian Magazine> [accessed 14 January 2022].

Figure 19: Ulet Ifansasti, Plastic waste in Indonesia, digital photograph, The Guardian, 2 January 2021, <‘Loophole’ will let UK continue to ship plastic waste to poorer countries | Environment | The Guardian> [accessed 15 January 2022].

Figure 20: John Mone, Protest of the DAPL, digital photograph, The Guardian, 9 February 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/feb/09/dakota-access-pipeline-biden-harris-letter-celebrities-indigenous-leaders> [accessed 13 January 2022].

Further reading:

J.Y. Tan, ‘Wolfwalkers, and what we lose in imperialism’, DeconRecon, 31 March 2021, <Wolfwalkers, and what we lose in imperialism – DeconRecon>

Kambole Campbell, ‘Wolfwalkers review’, Little White Lies, 26 October 2020,<Wolfwalkers review – A revisionist animated fable of utmost beauty (lwlies.com)>

Kayleigh Donaldson, ‘Wolfwalkers and the freedom of young female friendships’, SYFY, 21 September 2020, <TIFF 2020: Wolfwalkers and the freedom of young female friendships | SYFY WIRE>

Hannah Priest, She-wolf : a cultural history of female werewolves (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016)

Bibliography

Alter, Rebecca, ‘Wolfwalkers Is Giving Kids a History Lesson on the Horrors of Colonialism’ Vulture, 2021, <‘Wolfwalkers’ Is Giving Kids a History Lesson on Colonialism (vulture.com)> [accessed 14 January 2022]

Damore, Meagan, ‘Wolfwalkers Creators Break Down the Film’s True Villain & Message of Tolerance’, CBR, 2021, <Wolfwalkers Interview: Directors Discuss Film Message | CBR> [accessed 14 January 2022]

Faulkner, Joanne, ‘Negotiating vulnerability through “animal” and “child”’, Angelaki, 16.4 (2011), 73-85, <https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725X.2011.641346>

Ifansasti, Ulet, Plastic waste in Indonesia, digital photograph, The Guardian, 2 January 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jan/12/loophole-will-let-uk-continue-to-ship-plastic-waste-to-poorer-countries> [accessed 15 January 2022]

King, Gilbert, Mountain of 19th Century Bison Skulls, digital photograph, Smithsonian, 17 May 2012, <Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed | History | Smithsonian Magazine> [accessed 14 January 2022]

Mone, John, Protest of the DAPL, digital photograph, The Guardian, 9 February 2021, < https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/feb/09/dakota-access-pipeline-biden-harris-letter-celebrities-indigenous-leaders> [accessed 13 January 2022]

Phippen, J.W., ‘Kill Every Buffalo You Can! Every Buffalo Dead Is an Indian Gone’, The Atlantic, 2016, <“Kill Every Buffalo You Can! Every Buffalo Dead Is an Indian Gone” – The Atlantic> [accessed 10 January 2022]