Lynch has made a career out of the surreal, exploring the dark and often animalistic nature of human existence. His 1986 neo-noir mystery/psychological horror Blue Velvet centres around college student Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan), who after returning home after his father suffers a stroke, discovers a rotting human ear that leads him on an investigation related to a lounge singer named Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini) and a criminal gang who have kidnapped her son. His view of the idyllic town of Lumberton is gradually morphed into a violent, decaying and bug-filled horror as he becomes increasingly involved in its criminal underbelly, exposing his own animalistic violence along the way.

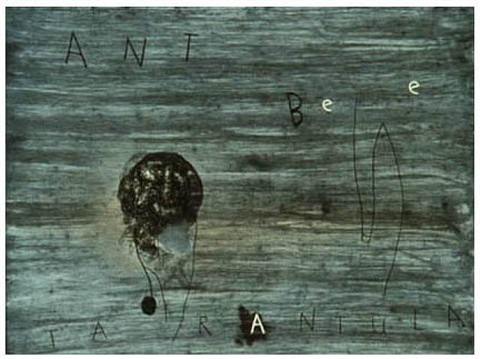

‘Ant, Bee, Tarantula’ David Lynch, 1998

The use of animal symbolism in the horror genre is abundant and links to the Freudian theory that animal phobia is an effective reaction on the part of the ego in danger, the danger being castration.[1] The film is highly sexual in nature, and the juxtaposition of the violent sexual acts committed to Dorothy with the up-close shots of ants in grass and crawling on the severed ear really elevate this subconscious level of discomfort, almost creating a sense of the uncanny. The animal depictions here are not just literal, Jeffrey seems destined to confront his own animality in the film. When he first meets Dorothy, he refers to himself as ‘the bug man’, the meaning of this alias becomes more layered as the film progresses.[2] As he becomes more intertwined in Dorothy’s criminal world, he becomes more feral, distancing himself from the innocent man we meet at the beginning of the film.

There is a distinct parallel at the beginning and end of the film, we see the same brightly colour-graded picket fence behind red roses, and most importantly, we see the same kind of large black ant. The contrast of these two images perfectly visualises Lynch’s idea of the seedy underbelly beneath the surface of beauty. In the opening sequence of the film, we see Jeffrey’s father collapsed suffering a stroke to the non-diegetic sound of Bobby Vinton’s Blue Velvet. The song begins to fade as he is lying on the ground, the visual distorts and we see this unsettling zoom in to the dog snapping at the water that is still running from the hose. The placement of the hose creates a phallic image, which the dog snapping and snarling at it heavily evoking this Freudian fear of castration. The shot then travels to an extreme close up of the grass and Vinton’s song is reduced to being almost inaudible. It is replaced with an unidentifiable squelching sound interpolated with a kind of buzzing or gnawing which was created using a contact microphone on termites.[3] The camera travels ever closer through the grass, creating these ominous dark visuals with indistinguishable blades of grass until it finally reaches its target, a large jittering mass of black ants. These up-close visuals disturb us as a viewer as they are too close for us to fully comprehend their true form or meaning, we can’t find their context which creates this sense of the uncanny and subconscious fear.[4] Lynch uses this visual lack of comprehension as an allegory for the way in which we are unable to comprehend the true nature of the world around us. When Jeffrey discovers the human ear, it is also covered in ants, this time smaller and less of an indistinguishable mass. The camera zooming into the hole in the ear serves to represent the opening of Jeffrey’s journey throughout the film, with the way in which it is decayed acting as foreshadowing for the corruption and horror he is about to encounter. The calmness in which he handles the ear is unsettling, making the viewer question whether there is more to his character than the innocent college student he is presented as.

We see this same imagery again in the film’s final sequence, a single ant captured by a robin. The sequence opens with another close up of a human ear, this time it is undamaged and the camera zooms out to reveal it is Jeffrey’s ear. If we continue with the idea of the hole in the ear symbolising an opening of a journey, this time it is a much more positive one, he has freed himself from this corrupt criminal world. The camera flits between Jeffrey lounging and a robin perched in a tree above him, he seems content and is called inside. In some cultures, robins act as a symbol for the rebirth of the spirit, and there is definitely a sense of bildungsroman with Jeffrey’s character. In a biblical context, the robin is depicted as picking a thorn out of Jesus’ crown, and as a result cuts itself, leading to it having this red breast of feathers. Much like the robin, Jeffrey will always be marked by his desire to pick apart this criminal underworld and has used it to grow and decide what kind of person he wants to be. Inside we see the animatronic bird again, this time it is in the centre of the frame, perched on the window ledge drawing the viewers eye straight to it. The robotic movement of the bird makes the visual incredibly surreal, it seems out of place in the real world around it. Aunt Barbara comments ‘I don’t see how they could do it. I could never eat a bug.’, which Jeffrey and Sandy (Laura Dern) find amusing and reply, ‘It’s a strange world isn’t it.’ Throughout the film, they have experienced things that, like the robin, seem out of place in this white-picket world they live in.

Jeffrey discovers the ear

‘I could never eat a bug’

Castration fears seem to tie in with the animality that is shown in the two main male characters in the film, Jeffrey and Frank (Dennis Hopper). Frank is portrayed as a true monster, his repetition of the line ‘Now it’s dark’ signifying how he has lost all traces of his humanity. He is incoherent and erratic and in his introductory scene his violence towards Dorothy in cut with him writhing around on the floor like an animal. He also demonstrates a kind of oedipal complex, making Dorothy call him ‘Daddy’, he asserts complete dominance over her almost like she is his prey. In a later scene he says to Jeffrey ‘I shoot when I see the whites of eyes’, this kind of eye being an animal characteristic, showing he feels threatened when confronted with someone who can reciprocate this feral nature. This castration fear in Frank is the reason he needs to assert dominance over those around him, but he is ultimately defeated by Jeffrey’s ability to embrace his humanity over his darker animal instinct. Already having briefly discussed the complexity of Jeffrey’s character, it is clear he is in constant conflict with his own curiosity and grapples with it exposes his feral nature or his humanity. He is described best by Sandy when she says ‘I can’t figure out if you’re a detective or a pervert.’ Linking back to the alias of ‘bug man’, Jeffrey acts as both a surveillance ‘bug’ through his acts of voyeurism and also as an animal through his treatment of Dorothy in their sexual relationship. Through watching Frank’s feral nature, Jeffrey goes on to imitate it and in doing so becomes what he is seeking to stop. The question of Jeffrey’s character is whether he is more of a parasitic insect, like Frank, or like the robin? In a biblical context, the robin was brave to pick a thorn out of Jesus’ crown, and in doing so cuts itself resulting in its distinctive bloody redbreast. Much like the robin, Jeffrey picks apart Frank’s criminal circle and will be marked with the experience. He chooses to love Sandy, drawing back to her dream of the robin’s symbolising love, rather than pursue his violent relationship with Dorothy. Ultimately, he chooses not to indulge in this feral animal instinct, demonstrating that to be truly good humans must reject their darker animality.

Frank vs Jeffrey: Animality vs Humanity

What is clear in Lynch’s representation of animals and human animality here is used to represent an inherent darkness and violence, his representations are designed to cause discomfort to the viewer. Embracing the surrealism of the horror genre, he uses animal characteristics to delve into the human subconscious and makes use explore our fears. The symbolism of the ants exposes us to the criminality and feral nature of the world we choose to ignore, with the up-close portrayal of this being upsetting and uncomfortable to the viewer. Meanwhile Frank’s lack of humanity represents to both the viewer and Jeffrey what can happen if we completely give in to our dark animality, acting as a warning. It is the men in the film who act as animals, with their toxic masculinity and constant quest for dominance showcasing their subconscious fears of being emasculated by the women around them. Frank’s ultimate defeat is brought about by love rather than intimidation or fear, demonstrating the need for us to face our subconscious fears and embrace our humanity.

[1] Barry Keith Grant, Film Genre Reader IV (Austin, Tex: University of Texas Press, 2012), p.273.

[2] Andreas Halskov, “16:9 – Juni 2012 – En Scenes Anatomi: Blue Velvet Og Det Nysgerrige Øre”, 16-9.Dk, 2012 <http://www.16-9.dk/2012-06/side07_anatomi.htm> [Accessed 2 June 2020].

[3] Kenneth C Kaleta, David Lynch (New York: Twayne, 1995),p,67.

[4] John Mullarkey, “ANIMAL SPIRITS: Philosomorphism And The Background Revolts Of Cinema”, Angelaki, 18.1 (2013) https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725x.2013.783439,p.24.

Filmography

Blue Velvet (dir. David Lynch,1986,USA)

Bibliography

Grant, Barry Keith, Film Genre Reader IV (Austin, Tex: University of Texas Press, 2012),p.273.

Halskov, Andreas, “16:9 – Juni 2012 – En Scenes Anatomi: Blue Velvet Og Det Nysgerrige Øre”, 16-9.Dk, 2012 <http://www.16-9.dk/2012-06/side07_anatomi.htm> [Accessed 2 June 2020]

Kaleta, Kenneth C, David Lynch (New York: Twayne, 1995),p.67.

Mullarkey, John, “ANIMAL SPIRITS: Philosomorphism And The Background Revolts Of Cinema”, Angelaki, 18 (2013) https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725x.2013.783439,p.24.

Further Reading

Atkinson, Michael, Blue Velvet (London: BFI, 2000)

Gregersdotter, Katarina, Johan Höglund, and Nicklas Hållén, Animal Horror Cinema (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2015)

Joseph, Rachel, ““Eat My Fear”: Corpse And Text In The Films And Art Of David Lynch”, Word & Image, 31 (2015), 490-500 https://doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2015.1053042

Lynch, David, and Chris Rodley, Lynch On Lynch (New York: Faber, 2005)