An inventor of dubious talent visits Chinatown trying to find his son a Christmas present, where he is sold a strange fluffy creature; a Mogwai. The creature comes with three rules: do not expose it to bright light, do not get it wet, and do not feed it after midnight. Within due time however, all these rules are disobeyed. The Mogwai, affectionately named Gizmo, reproduces, spawning mischievous reptilian Gremlins with an appetite for mischief and destruction.

Thus, mischief and destruction ensue.

In his 1984 review of Gremlins, prolific film critic Roger Ebert wrote, ‘Gremlins is a confrontation between Norman Rockwell’s vision of Christmas and Hollywood’s vision of the blood-sucking monkeys of voodoo island.’[1] This quote not only exemplifies the genre hybridity that comprises the narrative, but also the hybridity and duality at the film’s core. Boundaries between familiar and alien, domesticated and wild, and ultimately animal and human.

‘The idea of taking a 4-year-old to see Gremlins, thinking it’s going to be a cuddly, funny animal movie and then seeing that it turns into a horror picture, I think people were upset…’ [2]These are the words of Gremlins director Joe Dante when questioned about the critical reception the film had received among family audiences.

The 80s became the era of the Hollywood blockbuster where science fiction, action and horror were particularly popular, the former especially in no small part due to the commercial success of Star Wars. Gremlins was an experiment in heavy genre blending: the scares and gore of horror, the slapstick and mischief of comedy, and the sci-fi alien-like Gremlins at the forefront of it all. The inclusion of multiple genre properties allowed the film to reach a wider audience than any one genre could alone.

An Ewok from Star Wars Episode VI / WWII Gremlins Propaganda Poster

The film’s unexpected horror turn was not only responsible for scaring a significant number of small children, but was also responsible for the creation of a new PG-13 rating between PG and R[3]. In a cinematic tradition of violence, Gremlins is particularly adept at pushing ferocity further than audience expectations. A kitchen fight scene culminates in Gremlins getting repeatedly stabbed, mangled in a blender and even gruesomely overcooked in a microwave; all of which is displayed onscreen.

The origins of Gremlins as characters in folklore can be traced back to World War II, in a Roald Dahl story which detailed Imp like creatures interfering with the machinery on planes and causing mechanical failures[4]. This notion of Gremlins was utilised widely throughout Wartime propaganda, and is particularly recognisable in the Twilight Zone episode Nightmare at 20,000 feet[5]. In this respect Gremlins differ from other mythological creatures with their apparent understanding of human technology, which gives them a particular sci-fi edge. Despite keeping this technologically interfering element, scriptwriter Chris Columbus’ Gremlins are of an entirely different ilk however, particularly in their Mogwai (Cantonese for ‘Monster’) origins.

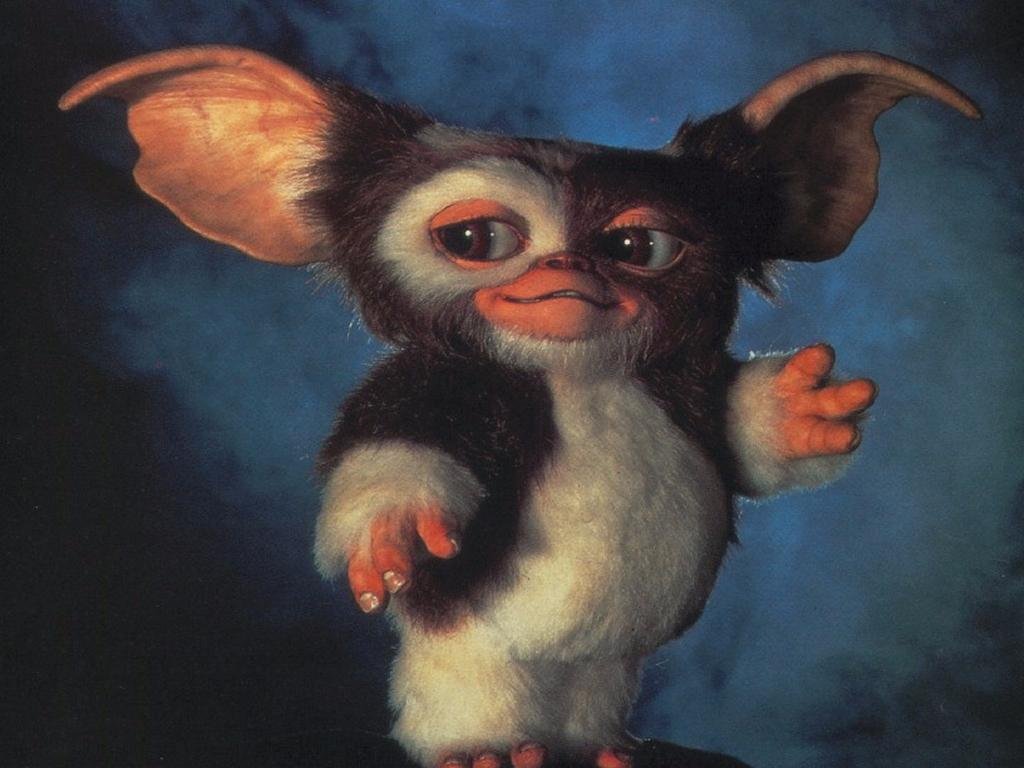

Gizmo, aside from his aversion to light and water, appears to thrive as a domesticated pet. He has the ‘cute’ aspect of a smaller pet such as a rabbit, but does not need a specialised hutch, as he is seen simply sleeping on an armchair with a pillow and blanket. His limited grasp of language, namely ‘bright light!’ serves to simply and effectively communicate his desires, as shown when he reminds Billy to turn the bathroom lights off before taking him in, and he also understands body gestures, such as shaking his head for no when offered chicken after midnight. This also shows a crucial understanding of the three rules crucial to his survival. As he watches television he pretends to be a race car driver, which displays an imaginative function like that of young children, and a playful side that makes him interesting to interact with, similarly with his ability to successfully hold a tune. Gizmo has no problem settling in or warming to a new household, and the family dog has no issue with him despite being entirely foreign. He is a well behaved, clearly intelligent, and ultimately likeable creature, ironically juxtaposed to his Cantonese title. In many ways, the Mogwai is much like a primate in its stature and characteristics. In this way, Gizmo is just as much ‘animalistic’ as ‘animal’. Gizmo being presented in such a manner also provides the audience with a nonhuman protagonist to follow; a sidekick to Billy that ensures every scene has a flavour of Freud’s ‘uncanny’[6].

Since Gizmo forms such an ideal pet however, it is almost second nature for the other characters to immediately see him as such, as the notion of animals as pets is so ingrained within society. Billy’s friend Pete immediately asks ‘Where can I get one of those?’ upon seeing Gizmo, and Billy’s inventor father even talks about capitalising on the creature’s offspring, which are produced asexually in contact with water – ‘they could replace the dog as the family pet.’ Even as an audience, it is simply accepted that should he desire, Billy’s father possesses the ability to value, price and sell animal life with a stake of ownership within a capitalist society. This later transpires to be a grim foreshadow for an alternate string of events when the Mogwai evolve into destructive Gremlins, not least through the Gremlins acting as a vehicle for parody of consumerist society. As the old man states in the first scene, ‘Mogwai is not for sale.’

Gizmo’s ‘offspring’, although near identical looking, are clearly defined from Gizmo, not least because of his attempts to distance himself from them; notably crying when he notices they have been born, possessing a knowledge of what will become of them. These Mogwai argue and fight with each other, make a mess, and don’t show an interest in the peaceful activities Gizmo engages in, such as hugging or singing. They have a clearly defined alpha of their group, who has a mohawk to stand out, and a pack mentality, as they are always seen together. A shot sequence of the group laughing in bed directly before a shot of the family dog tied up outside in the house fairy lights confirms the group’s mischievous intent, and a desire to complete a transition into fully formed Gremlins that Gizmo does not possess. Their plan to trick Billy into feeding them after midnight by tampering with his alarm clock displays one of the key characteristics of the Gremlins even in this pre-evolutionary stage.

The evolution from Mogwai to Gremlin is particularly sci-fi in nature. The process of fully formed creatures synthesising in a few hours is similar to Ridley Scott’s titular Alien character of 1979[7], and the concept of a race splintered into two subspecies differing in characteristics and values is a concept explored as early as 1895, with the peaceful Eloi and Flesh Eating Morlocks of H.G. Wells’ Time Machine[8]. This amalgamation of sources paired with a unique design help to create more believable creatures in a way, as they are formed of elements audiences have likely seen before. The asexual means of reproduction, as well as adding further to the mysterious origin and nature of the creatures, also acts as a crucial characteristic of the now antagonistic Gremlins, in that they can multiply at will in any body of water – as the Gremlin leader Stripe proves by jumping in the YMCA pool and creating enough Gremlins to overrun the entire town within hours.

Alien (1979)

As ‘villains’ of sorts, the Gremlins themselves are what set the film apart. There is no ulterior motive, master plan or even an end goal; they simply just want to cause disorder for disorder’s sake. Their lives are short lived and violent, and they damage in intuitive and often sadistic ways, from changing multiple traffic lights to green at once to rewiring a chair lift to run at breakneck speed, or simply driving a snow-plow straight into somebody’s house. This appetite for destruction is a trait that is otherwise exclusive to mankind, and alongside this trait the Gremlins also appear to possess a distinctly humanistic appetite for self-destruction. A scene takes place in a bar where Gremlins of all different styles of dress, representing different humanistic sub-cultures and classes, are engaging in loud shouting, fighting, heavy drinking and chain smoking. If the Gremlins do possess any human-esque qualities, they have been gifted some of the most objectively negative. This all culminates a particularly tongue-in-cheek scene, where the Gremlins are all sat watching Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarves in the cinema, laughing, singing and throwing popcorn around. Contrasted to the earlier scenes of aggression and bloodlust, this is the ultimate dig at the cinemagoing audience, using such a stark comparison as a source of humour and self-mockery.

On a much less unique but equally important note, the family dog, Barney, also has moments acting out of the ordinary throughout the film. Mrs. Deagle’s threat to kill him prompts him to leap up from under the desk and pounce on her, as if he understood her intent. Similarly, when he hears that Mogwai ‘will replace the dog as the family pet’ he audibly whimpers and looks upset. It is of interest in a film so focused upon the supernatural that the behaviour of a dog might slip notice, despite being not only comic, but helping to advance the plot.

The creatures within the film explore the best and worst of human traits from the context of outside humanity; a different channel of visualisation. Animals are represented as strange and exciting, as familiar and alien, but never truly ‘normal’ – even in the case of the dog. The concepts of pet keeping, pet selling, animal experimentation and human rights are called into question. The fact that an audience immediately sees Gizmo as an adorable animal and a Gremlin as an evil and unpleasant creature demonstrates the importance of appearance amongst animals, especially in terms of survival in a domesticated setting. Taking the idea of ET and wearing a variety of sci-fi inspirations very close to its chest, Gremlins presented in trailers what looked like some fun and light mischief, and then displayed what transpired to be dark comedy and light horror, challenging audience views on the representation of the creatures within. A Gremlin can be anything from a chain smoker in a bar wearing a bowler hat and sunglasses to a loud cinemagoer excited to watch Snow White. Gremlins represent the worst of what mankind can be. Not as a representation, they’re a ball of unadulterated mischief – a defining characteristic physically embodied.

Gremlins trailer

The final comment on both the Gremlins and the Mogwai comes with the return of the old man at the end of the film, who affirms these mystical creatures’ alignment with man. When Billy is shocked that the old man can speak Gizmo’s language, the old man replies, ‘To hear, one only has to listen’, and scorns Billy for ‘teaching’ Gizmo to watch television. His proverb ‘You do with Mogwai what your society has done with all of nature’s gifts’ resonates on an entirely different level. Man’s destructive nature is shown through the Gremlins themselves, but also through trying to own and control them.

Bibliography / Further Reading

[1] Roger Ebert, Gremlins Film Review (1984), <http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/gremlins-1984> [accessed 15 January 2017].

[2] Anthony Breznican and The Associated Press, PG-13 remade Hollywood ratings system (seattlepi.com, [n.d.]), <http://www.seattlepi.com/ae/movies/article/PG-13-remade-Hollywood-ratings-system-1152332.php> [accessed 15 January 2017].

[3] ibid

[4] Roald Dahl, The Gremlins – Goodreads (Goodreads, 2017), <https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/6677.The_Gremlins> [accessed 15 January 2017].

[5] Nightmare at 20,000 feet, dir. by Richard Donner (1963).

[6] Sigmund Freud, Freud’s ‘The Uncanny’ (1919), <http://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/freud1.pdf> [accessed 15 January 2017].

[7] Alien, dir. by Ridley Scott (1979).

[8] Bartleby, Wells, H.G. 1898. The time machine (1993), <http://www.bartleby.com/1000/> [accessed 15 January 2017].