Benedikt Erlingsson’s directorial debut Of Horses and Men (2013) is best described as a series of interlocking fables, focusing on six sets of neighbours living in an isolated Icelandic valley. Linked by their passion for horsemanship, the vignettes introduce us to: a courting couple with equally frisky horses; an alcoholic whose penchant for hard liquor sees him take his best swimming horse out to a Russian trawler at sea; a Spanish tourist learning to ride; feuding neighbours at odds over ancient bridleway rites; and a young woman desperate to prove her riding skill in a male-dominated world. Horse and human relationships play out alongside each other as the horses and their owners experience the trials of life and death in this deeply entertaining film poised on the edge of tragedy and comedy.

Erlingsson’s hybridisation of genre feels truly Icelandic: the delicate balancing of tragedy and comedy a reflection of the recognisably Nordic dark sense of humour (gálgahúmor in Icelandic). [1] More broadly, the film assumes an arthouse style that prioritises the aesthetic over narrative fluidity. Minimalistic dialogue is interspersed with still, photograph-like shots of both horses and landscape that illustrate the film’s commitment to sharing and celebrating Iceland’s unique and beautiful natural offerings. Of Horses and Men’s narrative structure of vignettes strengthens this aesthetic approach, providing the audience with quirky portraits of rural living. Despite not being a traditionally realist film, Erlingsson’s dedication to the real is evident throughout: the central relationship between horses and humans that is so integral to Icelandic culture, remote landscapes and rural living is certainly not a fiction.

The original Icelandic title of the film, Hross í oss (Horse in Us), seems a more fitting title for a film dedicated to portraying the co-dependent relationship between its human and horse characters. This theme is most apparent in the visual motif of a horse’s eye, with a human reflection, that introduces each vignette. With Erlingsson’s negation of traditional narrative form, the motif becomes a marker for the audience of a change in plot direction. However, the motif also functions symbolically: the eye’s reflection of its owner and/or the landscape suggests the convergence of horse, human, and landscape as one – spiritually connected through the symbol of the eye. Despite the symbolic potential of the horse’s eye motif, this choice of shot is also a clear statement on the film’s ethical stance on the treatment of animal characters in film. At no point throughout Of Horses and Men are we offered a point-of-view shot from the horses, the eye motif being the closest we get to the horses’ look. The barrier between audience and animal character this anthropocentric shot creates functions as a respectful acknowledgment of the impossibility of representing the interiority of another animal.

Jonathan Burt has argued that ‘the exchange of the [human/animal] look is, in the absence of the possibility of language, the basis of a social contract’ and to a certain extent, a look does operate as an acknowledgment of the presence of another. [2] Erlingsson’s direction seems to embody this very philosophy: throughout the film there is a fascination with eyes and looking, not just concerning the horses but the humans also, who are often spying on each other through binoculars. Coupled with the minimalistic dialogue, both audience and character are invited to participate in a visual type of communication, observing actions and body language. This prioritisation of the visual over the spoken in communication also elevates the position of the horse who also communicates in the same language as the film.

It is important to note that Of Horses and Men is not a film about horses in general, but a celebration of the unique breed that is the Icelandic horse. The figure of the Icelandic horse is integral to the country’s rural identity, enshrined in both ancient Nordic mythology and modern law. As the importation of other varieties of horse is prohibited across Iceland, the breed has been bred pure for the past 1,000 years. The Icelandic horse is distinguishable from other breeds by its small, pony-like stature and its possession of five natural gaits instead of the usual three. In one of the opening scenes of the film, during a ride to his neighbour Solveig’s (Charlotte Bøving) house, Kolbeinn (Ingvar Eggert Sigurðsson) showcases his mare’s proficiency in the Icelandic gaits (the tölt and the flying pace) to the admiration of the voyeuristic neighbours who watch each other’s every move through binoculars. The character’s pride in his horsemanship is inscribed through subtle character details in the opening of the film: the medals and trophies displayed in his house; his vanity that won’t allow him to ride with a button out of place; his smug smile as he realises his neighbours are watching his riding. Whilst Kolbeinn’s pride in his mare may be viewed as an extension of his vanity, cinematographer Bergsteinn Bjorgulfsson’s direction of the camera honours the physicality and skill of Kolbeinn’s mare. During this scene, the camera is often placed at a close-up to the horse’s legs, with Kolbeinn out of shot. This is a continuation of Bjorgulfsson’s tactile treatment of the mare in the opening shot: an extreme close-up of the horse’s textured hide. Even once Kolbeinn arrives at Solveig’s house, the camera largely remains outside with the mare Grána whilst we observe the human interaction through the window. The screen time afforded to the horses in the film and the shooting of them in scenes absent of any human characters deems the horses characters in their own right, worthy of our attention.

As characters in their own right, there are moments in the film where the unrestrained animality of the horses disrupts the anthropocentric narrative. The most vivid example of this immediately follows Kolbeinn and Solveig’s meeting, as Kolbeinn mounts his mare to ride back home. Whilst the humans have their coffee date, another courtship ritual is taking place outside between the horses. Solveig’s black stallion pronounces his desire to mate with Kolbeinn’s mare by baring his teeth and whinnying, and she returns the display by urinating and lifting her tail. If these signals require knowledge of horse behaviour unbeknownst to you, at least no one can miss the connotations of the stallion’s erect penis. The black stallion breaks free from his enclosure as Kolbeinn begins to ride his mare home, and Kolbeinn is unable to prevent the inevitable. In a delightfully outrageous moment of cinema, the stallion mounts the white mare with Kolbeinn still mounted on top of her. Calum Marsh, in his Sight and Sound review of the film, asserted that the ‘impromptu sex act is a stand-in for what Solveig wishes Kolbeinn would do to her’, but this type of reading reduces the horse characters to symbols through which to understand human interactions. [3] Instead, the unbridled (!) carnality of the horses seems to enact the animality of sexual attraction that human social convention has restrained. In this scene, the horses also possess agency outside of their owners’ control: Solveig’s black stallion cannot be restrained by her fence and Kolbeinn’s mare will not move, despite his loud protestations.

Stella Hockenhull has noted that Erlingsson’s film acknowledges the animal’s ‘right to idiosyncrasy and choice within its natural environment’ and this is evident in the horses’ ability to direct the narrative, to a certain extent. [4] In one of the final vignettes, we are introduced to Jóhanna (Sigríður María Egilsdóttir), a young woman attempting to herd a group of horses with some colleagues. Due to a mistake by one of the men, four of the skittish horses escape, taking the focus of the camera with them. This is another instance of the horses in the film possessing enough agency to disrupt the anthropocentric narrative, not only do they greatly inconvenience the human characters but command the audience’s attention away from the humans as the following shots are solely of the escaped horses running free.

Despite these moments of animal agency in the film, ultimately the horses occupy a marginal position as service animals that come under the control of their human owners. After their moment of freedom, the escaped horses are re-captured by Jóhanna who tells them: “I’m the boss now.” Her accomplishment in re-capturing the horses finally earns her the respect with her male counterparts that she has been seeking: symbolised by them in the sharing of their alcohol and snuff with her as congratulations. However, Jóhanna’s acceptance into the masculine realm of horsemanship is only possible through her ability to subdue and dominate nature, re-asserting an anthropocentric, patriarchal and hierarchical worldview. The theme of the hierarchies of nature is again picked up in the final vignette of the film, that of Juan (Juan Camillo Roman Estrada). A Spanish tourist, Juan accompanies a group all learning to ride as they set out across the valley. Due to his inexperience, he falls behind until the group is completely out of sight and he is lost. As night falls, Bjorgulfsson’s blue filter comes into effect, accentuating the freezing conditions both Juan and his horse face. In arguably the cruellest and most gruesome scene of the film, Juan decides to kill his horse and use its carcass to prevent himself from freezing to death. His decision, coupled with a complete lack of retribution for his actions once he is found, legitimises Juan’s anthropocentric assumption that his wellbeing is more important than that of a non-human animal.

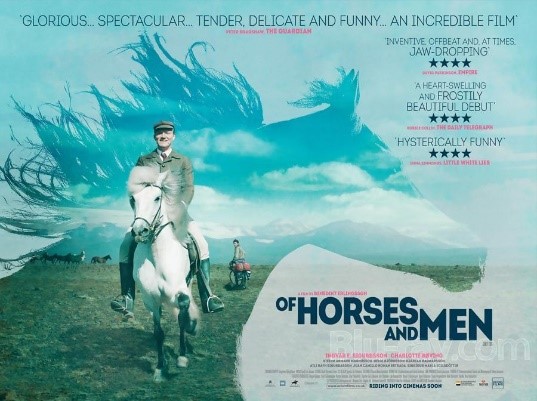

The most striking aspect of the representation of animals in Of Horses and Men for me was the commitment to honouring the reality of the horses, as opposed to reducing them to mere sign or attempting to animate them through anthropomorphisation. Hockenhull, in her assessment of the film, captures this sense of realism the film achieves through its treatment of the horses: ‘The horse produces a performance for the spectator, not as an actor, or one that can be considered anthropomorphically, but as a horse whose options can be interpreted through an understanding of animal behaviour, notwithstanding that she is constrained to an extent by the language of the film.’ [5] An understanding of horse behaviour, in addition to knowledge of the unique qualities of the Icelandic breed and its revered status in Icelandic culture clearly enriches the enjoyment of this film in which the appreciation of horses is central. The film assures this type of reading in its closing credits which read: ‘No horses were hurt in the making of this film. The entire cast and crew are horse owners and lovers.’ The respect for this animal is evident throughout, from the various close-ups of horse textures, to the promotional images for the film in which a horse’s silhouette dominates, to the screen time afforded to the horses, scenes often totally absent of any human characters. Skill in horsemanship is presented as an affinity with nature, spiritually joining the human, the animal and the landscape together. Ultimately, the horse and its owner are companions who face love, life and death side-by-side. However, despite the film’s respectful treatment of its horse characters, there is an underlying anthropocentric attitude that surfaces at points: when Kolbeinn shoots his mare as revenge for his humiliation, or when Juan kills his horse to aid his survival. It seems that the marginalisation of animal bodies is so engrained in human culture that even a film made by self-titled ‘horse owners and lovers’ cannot escape from replicating this very marginalisation at points. Of Horses and Men also maintains its currency through its discussion of contemporary horsemanship issues such as bridleway rites, horse tourism and the masculine gendering of the sport. Over all, the film’s fresh attitude towards animal characters that honours their abilities and their natural environment without patronising characterisation marks an exciting potential for changes in the way animals are treated on and for film.

[1] Emma Jones, ‘Is Nordic humour too dark for the rest of the world?’ BBC Culture, 2015 <http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20151012-is-nordic-humour-too-dark-for-the-rest-of-the-world> [accessed 09/01/2019].

[2] Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film, (London: Reaktion, 2002), p.39.

[3] Calum Marsh, ‘Review: Of Horses and Men’, Sight and Sound, 24 (2014), pp.82-83, p.82.

[4] Stella Hockenhull, ‘Human and Non-Human Agency in Icelandic Film: Of Horses and Men’ in Shared Lives of Humans and Animals: Animal Agency in the Global North ed. by Tuomas Räsänen and Taina Syrjämaa (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017) pp.24-36, p.25.

[5] Ibid, p.28.

Further Reading

Au Hasard Balthazar (Robert Bresson, 1966) – another film where a natural, or non-acting animal is central.

Under the Tree (Undir trénu) (Hafsteinn Gunnar Sigurdsson, 2017) – another Icelandic tragi-comedy about feuding neighbours that use their pets as pawns in their conflict.

Carlos Aguilar, ‘Interview: Benedikt Erlingsson on his film Of Horses and Men’, IndieWire, 2014, accessible at: https://www.indiewire.com/2014/03/interview-benedikt-erlingsson-on-his-film-of-horses-and-men-168870/

Guðrún Helgadóttir, ‘The Culture of Horsemanship and Horse Based Tourism in Iceland’, Current Issues in Tourism v9.6 (2006), pp.535-548.

Jacques Derrida, trans. by David Willis, ‘The Animal That Therefore I Am (More to Follow)’, Critical Inquiry v.28.2 (2002), pp.369-418.

Bibliography

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film, (London: Reaktion, 2002).

Hockenhull, Stella, ‘Human and Non-Human Agency in Icelandic Film: Of Horses and Men’ in Shared Lives of Humans and Animals: Animal Agency in the Global North ed. by Räsänen, Tumoas and Syrjämaa, Taina, (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017) pp.24-36.

Jones, Emma, ‘Is Nordic humour too dark for the rest of the world?’ BBC Culture, 2015 http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20151012-is-nordic-humour-too-dark-for-the-rest-of-the-world.

Marsh, Calum, ‘Review: Of Horses and Men’, Sight and Sound, 24 (2014), pp.82-83.